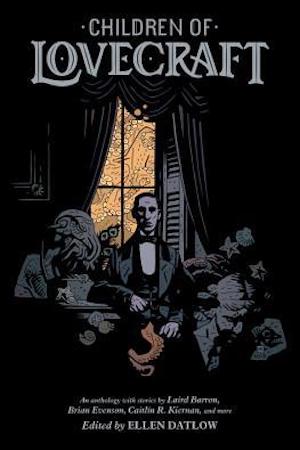

Welcome back to Reading the Weird, in which we get girl cooties all over weird fiction, cosmic horror, and Lovecraftiana—from its historical roots through its most recent branches. This week, we cover Caitlin Kiernan’s “Four Excerpts for An Eschatology Quadrille,” first published 2016 in Ellen Datlow’s Children of Lovecraft. Spoilers ahead!

“In this light and at this hour, it’s almost beautiful, the way that so many poisonous things are beautiful.”

Excerpt One, June 1969, West Hollywood:

Maxie Honeycutt, aka Paranoid Jack, is bedeviled by conspiracy theories from how aliens killed the Kennedys to how NASA’s electromagnetism is screwing up his wristwatch. You wouldn’t expect such a nervous guy to engage in “questionable business ventures.” But here he is at a go-go dive with Charlie Six-Pack, an associate of “the Turk.” Charlie wants Maxie to babysit something until the Turk’s back in town. The fist-sized jade figuring sits between them in a greasy paper bag, but Maxie wants nothing to do with it.

Charlie got the “idol” from a Brigham Young professor who claimed it belonged to a Donner Party survivor. Patrick Breen found the figurine in the mountains; when the party was stranded by a blizzard, the cannibalism was the figurine’s suggestion. The Turk’s got an Australian buyer lined up. Hold it a couple days, and Maxie’ll get a nice cut.

Maxie’s more worried about “heavy Apache hoodoo horseshit.” That night he has a terrible nightmare. Sunrise finds him clutching a whiskey bottle, trying not to think about the figurine, “or blizzards or a raw January wind howling through high mountain passes.”

Excerpt Two, January 2007, Atlanta:

Mike, an Atlanta policeman, recalls Esme Symes, who made a living reading palms and “telling rubes what they’d want to hear about their futures.” But she also had a knack for spot-on tips for finding victims’ remains.

Esme provides a tip about a derelict warehouse; Mike and partner Audrey respond. Inside, they find a fourteen-foot great white shark suspended from the ceiling above an enormous red-sand design. Instinctively, Mike avoids treading on the mandala.

The shark’s been gutted and sewn back together with fishing line. Red-nailed fingers stick out between stitches, still moving. Mike hacks the shark open to reveal a naked woman, barely alive. Audrey discovers she’s been sewn into the shark, hands around a jade figurine Mike describes as “evil, true and absolute”. But backup officers have to pry it from his grip.

Esme hangs herself in an apartment wallpapered with sketches of the figurine. She must have realized she was a suspect. Guilty or not, Mike thinks Esme “got off scot-fucking-free.”

Excerpt Three, December 1956, west of Denver:

Archaeologist Ysabeau writes to her “Dearest Ruth” aboard a California-bound train. She’s returning from a trip east where she met Dr. Adelie Marquardt, who shares her interest Semitic-Mesopotamian fertility gods. A mutual friend urged Ysabeau to tell Ruth what happened between her and Marquardt, with whom Ruth has had firsthand disturbing experience.

Ysabeau finds Marquardt engaging; the woman flatters her publications and offers to show her an artifact recovered from Syria. Ysabeau accepts an invitation to Marquardt’s Benefit Street house. She finds a gathering of the sort of Bohemians she usually avoids. She meets Marquardt’s Romanian companion Ecaterina. A naked young man kneels before the fireplace, crowned with ivy and blindfolded. Two women flank him, holding silver chalices. Just a game, Marquardt assures her. With Ecaterina, they retire to an adjacent library, where the artifact awaits.

Ysabeau gasps. The figurine’s of exquisite craftsmanship, yet it’s “in all ways hideous…a wicked thing,” from which Ysabeau can’t look away. Found in Ugarit ruins, it likely came from Amenemhat III’s Egypt. It doesn’t represent Dagon, nor Dagon’s wife Ishara, but perhaps the “Mother Hydra” its discoverer Schaeffer described. Schaeffer sold it to the Frenchman Moreau: a believer in sunken civilizations, including R’lyeh, where dwelt Dagon and Hydra and a much mightier god to be resurrected by an apocalyptic flood. Moreau would eventually murder eight people. There were allegations of cannibalism –

A wounded-animal cry interrupts Marquardt. Ysabeau remembers the naked boy as Marquardt apologetically hustles her out through a side door. Shaken, Ysabeau leaves Providence the next day. Afterwards, she receives a clipping about a naked male corpse pulled from the Seekonk River, its eyes and tongue cut out.

Ysabeau urges Ruth to “stay away from that woman.”

Excerpt Four, April 2151, Isle of Brooklyn Proper:

From her apartment house roof, Inamorata observes an oil spill off Prospect Beach. It’s prismatic, almost beautiful, like “so many poisonous things.” Geli, her lover, arrives. She’s a former beachcomber whom Inamorata has gotten registered as a legal picker of whatever the drowned world pukes up. This morning she’s recovered a jade figurine.

The figurine reminds Inamorata of her mother’s stories of the troll who lived under the ruined Williamsburg Bridge. It’s exaggeratedly female, full breasts and hips and buttocks, even the vulva depicted. Its eyes bulge, fish-like, and its belly sprouts anemone-tendrils.

Sirens wail from the hurricane warning towers, and yet the sky remains cloudless. Inamorata lifts her spyglass. The oil slick drifts nearer Prospect Beach, though currents should be pushing it away. Gulls dive headfirst into the slick and disappear. She remembers her mother imitating a troll’s voice.

The sirens scream on.

The Degenerate Dutch: Probably, Charlie says, the idol was carved by the Apaches or the Incans.

Libronomicon: Some New Yorker wrote a book about the woman sewn into a dead Great White Shark. Sounds like a real page-turner.

Weirdbuilding: Ysabeau’s section takes place entirely in Providence, up the hill in Lovecraft’s neighborhood, with a significant scene in what I’m pretty sure is the Shunned House. Here you’ll find experts on Dagon and Hydra, and deities less mentionable.

Madness Takes Its Toll: Crazy “Paranoid Jack,” “loonier than a run-over dog,” has a surprisingly good sense of self-preservation when it counts.

Anne’s Commentary

In her introduction to Children of Lovecraft, Ellen Datlow faces the perennial question: “What makes Lovecraft still relevant today?” She credits the innate creepiness of “his vision [of] Elder Gods that control human destiny.” It’s this “terror of the cosmic unknown” that she encourages her contributors to mine.

Surely a cosmos is playground enough to share. Start on the original swings and monkey bars, then erect your own “play” structures. Some may cling to the old park benches and grouse that only their splinters are sufficiently soul-piercing; others will gladly sample fresh devices of horror and wonder.

Kiernan’s contribution was the first I read. I can never resist a title that challenges me to figure it out. “Eschatology” rang a faint bell, something about the end of the world? From Merriam-Webster, “a belief concerning death, the end of the world, or the ultimate destiny of humankind.” More specifically, it’s “Christian doctrines concerning the Second Coming, the resurrection of the dead, or the Last Judgment.” Jane Austen taught me that a quadrille’s a ballroom dance. More specifically, it’s a dance performed by four couples in a square formation; “Excerpts” does dance out four substories.

“Excerpts” reminds me of Lovecraft’s “Call of Cthulhu,” which also deals with eschatological issues, such as Great C’s resurrection and the end of humanity. Its three sections, like Kiernan’s four, provide increasingly worrying glimpses of mysterious cults. Both end in Second Comings, though Cthulhu’s is thwarted by the premature resinking of R’lyeh, while Mother Hydra shows only her oily surface “halo” before fade-out.

“Call” centers on investigations into the Cthulhu cult first pursued by Professor Angell and continued by his great-nephew. “Excerpts” ranges in nonchronological order through the 20th and 21st centuries before ending in 2151. Each section features unique characters and a different narrative style. Figurines representing Hydra link the sections.

Section One’s point-of-view is difficult to classify. I’d call it third person omniscient except that the narrator “speaks” in a noir-hipster lingo like Charlie Six-Pack’s. Maybe the omniscient narrator adopts the setting’s “overheard” vernacular. Maybe Maxie’s telling his story in the voice of ever-hectoring Charlie. Nothing overtly supernatural happens, although Charlie’s figurine gives Maxie nightmares even after he refuses to “babysit.”

Section Two, January 2007, has a first-person narrator in Atlanta policeman Mike. It reads not like a written report, but like Mike telling his story informally, his profanity-laced vernacular uninhibited. Unlike Maxie, he witnesses the aftermath of cult activity. I doubt Maxie ever touched Charlie’s figurine. Mike holds the one he takes from the victim and knows it for “evil, true and absolute”—it stares back at him like Nietzsche’s abyss, and later responders must pry it from his fingers.

Psychic Esme kills herself amid sketches of the idol. Mike suggests she might have been a cultist. I think she might have drawn the idol from what her clairvoyance revealed, as Lovecraft’s sculptor Wilcox depicts Cthulhu from dreams.

Section Three, December 1956, is first person, epistolary style. Ysabeau resembles the typical Lovecraft protagonist, being an academic too rational to believe in her objects of esoteric study. The believers are Marquardt and Ecaterina, who from her red eyeshine may be a werewolf. Ysabeau may be gay, but she’s unaccepting of the “Bohemian” women and “effeminate” men at Marquardt’s party; nor are naked, rouged and blindfolded boys part of any “games” she’s used to playing.

Marquardt’s figurine immediately captivates Ysabeau; she knows it’s “wicked” and “vile,” but can’t look away. Meanwhile Marquardt supplies the idol’s history, from ancient Egypt to Ugarit Syria to its discoverer Schaeffer and its buyer Moreau. Though an exact description awaits Section Four, Ysabeau implies its female characteristics rule out a representation of Dagon or even his wife Ishara. Marquardt believes it represents another “wife,” Hydra. Schaeffer’s workers fled when he unearthed it. Little wonder, if Moreau was right about Hydra and Dagon dwelling in sunken R’lyeh, waiting for the global flood.

Ysabeau’s saved from touching the idol by a scream and Marquardt hustling her away. Later an anonymous clipping confirms the scream probably did come from the blindfolded boy.

Ysabeau knows that Marquardt’s residence was built in 1763 by Stephen Harris, whose misfortunes earned the place a reputation as cursed. She evidently doesn’t know 135 Benefit is where Lovecraft set “The Shunned House.” No wonder the address suits Marquardt.

Section Four, April 2151, is set after the apocalyptic flood that real-world climate change predicts. New York City’s inundated, leaving only isolated above-water bits where some can afford hilltop apartments while others scrounge through shoreline trash. Civilization’s not quite dead. There’s still salvageable oil when ancient storage tanks rupture undersea. There are still communications networks and hurricane sirens.

Third-person narrator Inamorata’s a hilltop dweller, whose lover Geli’s a “sanderling girl” she salvaged from among the beachcombers. Inamorata describes Geli’s new-salvaged figurine as a voluptuous woman with bulging fish-eyes and sea-anemone tendrils whose maker “meant to convey something terrible.” She thinks of a bridge troll from her mother’s fairy tales. Unsettling, how that oil slick drifts beachward when the current should be carrying it away. How gulls sacrifice themselves to its black maw. How she associates it with Geli’s find.

Then sirens start screaming as if to herald a Second Coming. It’s the perfect ending, leaving us at the moment when Inamorata’s unease escalates, for all the good panic will do reduced humanity.

Not, I suppose, that any humanity could long stare into the living Hydra’s eyes.

Ruthanna’s Commentary

Seventies through eighties Marvel comics had an unfortunate tendency to try and sound hip by having characters use pseudo-current slang. “Pseudo” because the writers were neither actual youths nor actually particularly hip; this was pretty easy to spot even as a non-hip youth in the 90s when I read the back issues. I regret to say that my experience reading “Excerpts,” which is doing some very cool things with cross-era artifact tracking, was not improved by the Dazzler flashbacks. I kept expecting a mutant pop star to dart through on roller skates, an image only made more plausible by that one time Magneto took over R’lyeh.

So this cat Maxie did not draw me in, nor cause me to worry over-much about the jade idol in a grease-stained bag. Okay, maybe I worried a bit about what happens when supernaturally repulsive idols are stored with babysitters reeking of doobie smoke. My eldritch abominations must come from smoke-free storage, thank you very much.

Then we go from someone paranoid about “pigs” to a jaded obscenity-spouting cop circa 2007. This pseudo-dialect seems drawn from hyperviolent police dramas, with a side order of Buddy From New Orleans Who Has Seen Some Call of Cthulhu. At least no one tries a Cajun dialect, because expecting Gambit to show up wouldn’t help the Dazzler problem.

In the third excerpt we jump back to 1956 and the language gets more academic—something I can personally report comes more naturally to many genre authors than 70s disco slang—and the characters more three-dimensional and also queer. Ysabeau specializes in Mesopotamian fertility gods, and is writing to (I suspect) lover Ruth who specializes in… something that involves spending too much time around cultists. Dr. Adelie Marquardt specializes in running cults and providing infodumps. Here we finally confirm that the jade statue depicts Hydra (not Cthulhu as I first assumed), and that it doesn’t just feel repulsive but cause people to do repulsive things. Here also we get to the titular eschatology, in the form of a great flood that will herald the resurrection of “a still mightier being than either Dagon or his wife.” Cthulhu seems to fit that bill.

Finally, we find ourselves in the future—possibly at the time of that great flood. For sure there’s sea level rise, not so different from elder god rise. It’s reminiscent of Livia Llewellyn’s “Bright Crown of Glory”. Inamorata and Geli look for scavengeable resources; Geli’s maybe got a touch of Innsmouth in her veins. And Cthulhu in His Aspect as Oil Slick is unpleasantly imminent.

Four segments, jumping around in time. One artifact, tying everything together—and hints of what it does between times. Both in these segments and in between, it attracts and repulses those who find it, and encourages those who hold onto it to start cults and sacrifice victims—in service of bringing about that flood?

So what are these four excerpts from? And what’s An Eschatology Quadrille that they’re for?

“From,” I would guess, is the full history of the jade idol, and the full set of bloody rituals that it orchestrates toward its eschatological ends. Each is narrated by a different scribe, some directly involved in the action and some mocking from the sidelines. So the history is also an anthology, with witnesses for documentation as important as high priestesses and sacrificial victims.

A quadrille is a dance for four couples, evolved from what was originally a military parade formation. It’s ancestral to square dancing; make of that what you will. So here we have four pairs of people involved in the “dance” of the end of the world. Maxie and Six-Pack, cop guy and Audrey (or Esme?), Ysabeau and Ruth (or Marquardt and Ecaterina), Inamorata and Geli. Okay, so it’s not the most symmetrical quadrille. And it’s danced to nasty stories rather than opera melodies.

But the grand finale, that part is going to be absolutely spectacular. Too bad the participants will be too busy screaming to appreciate it.

We’re off for July 4th. In two weeks, Louis probably doesn’t follow good advice in chapters 19-21 of Pet Sematary.