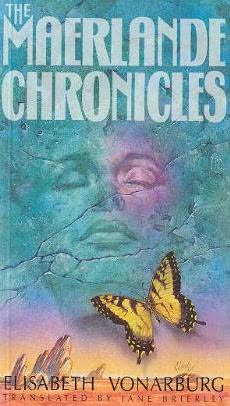

Elisabeth Vonarburg is one of the Guests of Honour at this year’s Worldcon, Anticipation, to be held in Montreal next week. She writes in French, and she’s one of the best and most respected French science fiction writers. Unfortunately, not much of her work is available in English, and what little is available tends to only be available in Canada, because of oddities of paying for translation. She has been fortunate in having excellent translation, especially with the book first published as In The Mothers Land and now as The Maerlande Chronicles. (French title: Chroniques du Pays des Meres). This book was published in English in 1992 in a Spectra Special Edition, or in other words an ordinary mass market paperback, and I bought it in an ordinary bookshop.

There are a number of feminist books where the world is reimagined without men, from Joanna Russ’s The Female Man through Nicola Griffith’s Ammonite. There are also books where men and women live apart like Sheri Tepper’s The Gate to Women’s Country and Pamela Sargent’s Shore of Women. All of them tend to share a certain hostility towards men, almost a revulsion. Reading books like this I read men as revolting rough aliens, not very much like the actual men I interact with in real life.

Vonarburg’s book, while doing some of the same things, is really different in this respect. This is a future Earth. There’s been nuclear war that has left badlands and mutations, and there’s a plague that kills children—around thirty percent of girls and one percent of boys make it to the age of seven. This is a continuing situation, it has lasted for hundreds of years, and society has adapted to it—in pretty much all the imaginable ways that involve maximising possible fertility. There have been Harems where men were in charge, and Hives where women were, and now there’s a society based on consensus united under a pacifist religion where the few men there are live to offer service. Also, this isn’t what the book is about. It’s about a new mutation of empaths, and how one girl with this empathy struggles with history and identity. This is very much Lisbei’s story. It’s the story of how she learns her world and her place in it and then overturns that. And it’s the story of how she learns that men are people. But what it’s really about is history and stories and the way we construct them.

I don’t have any idea what a real society of mostly women would look like. What Vonarburg shows us is far from utopian. She also shows us lots of different ways it can work. We begin with Lisbei as a childe (all words are in their feminine forms, which must have been even more noticeable in the original French) in a “garderie” in Bethely. (“Garderie” is normal Quebec French for what I’d call a kindergarden, or daycare. I encountered it first in this book, and I twitch when I see it used normally in Montreal.) Children do not leave this garderie until they are seven, though they progress from level to level. Children under seven are called “mostas” (from “almost”) and taught very little and interacted with minimally, because so many of them die. It’s just too hard for mothers to bond with them. They are handed over to the garderie immediately after birth. Lisbei is solitary until when she is six she bonds with another mosta, a girl called Tula. (The garderie has lots of girls and three boys.) Tula is her sister, though she doesn’t know it, and they share the mutation that Lisbei called “the light,” the empathic faculty.

The book spirals out from there, we discover that this system isn’t the same everywhere in Maerlande, in Wardenberg and Angresea people live in families with their children dying around them, in some other places they are even stricter than in Bethely. But everywhere children wear green, fertile people (men and women) red, and those infertile, past their fertility, or whose children are monstrous, wear blue. Being blue is felt as a shame, but in some ways it’s a sign of freedom to go where you want and do what you want instead of incessantly bearing children.

The world is weird and weirdly fascinating. Lisbei’s consciousness raising about the issue of men’s liberation is very well done. The center of the book though is the question of interpretation of history. Lisbei finds a notebook that simultaneously confirms and calls into question one of the central characters of their religion. It’s as if she found the diary of St. Peter and it half confirmed and half contradicted the gospels—about that controversial. Through this, and through the technical device of making the book partly formed of letters and diaries and reflections from Lisbei’s future on her past, Vonarburg explores the question of what history is and how and why we make narratives out of it.

This is an excellent and thought-provoking book that many people would enjoy. It gives Anglophones an opportunity to appreciate Vonarburg’s fiction in such smooth English that you wouldn’t guess it was translated, while keeping a flavour of the way the language was feminized in French. It was shortlisted for the Tiptree Award in 1993, and for the Philip K. Dick award.

A collection of Vonarburg’s short stories in English is being published at Anticipation by new Canadian small press Nanopress, it’s called Blood Out of a Stone and has an introduction by Ursula Le Guin.