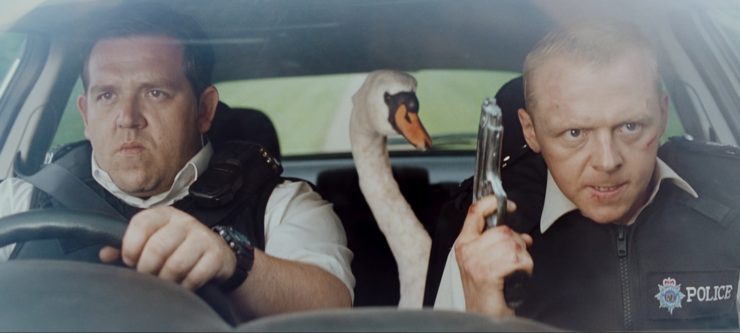

Edgar Wright’s 2007 Hot Fuzz is a kind of inverted mirror image of his previous film, Shaun of the Dead. In Shaun, the zombie genre is split open to reveal a relationship comedy nestling amidst the soft, bloody innards. Hot Fuzz, in contrast, starts as a relationship comedy before buckling on the violent accoutrements of an aggressively, and gloriously, empty genre exercise. For those who love cop films, and for those who hate them, the hollow explosion of policing is a kind of hot fuzz heaven.

Like it’s predecessor, Hot Fuzz is part of the Three Flavours Cornetto Trilogy, a series of films united by references to ice cream and a consistent creative team including Wright, producer Nira Park, and an ensemble cast. Most notably, Simon Pegg, who played the hapless loser title character in Shaun of the Dead, is cast dramatically against type as hyper-competent, uptight, upright London police officer Nicholas Angel. Angel is so good at his job that he makes everyone else in the London police force look bad. So his exasperated but unfailingly polite superiors reassign him to Sandford, Gloucestershire, a small town which wins “Village of the Year” regularly, and has virtually no crime. In Sandford Pegg is partnered with the useless but eager Danny Butterman (Nick Frost). Angel tries to teach Danny about serious police work while Danny tries to teach Angel about friendship.

That’s a formula for a sweet police buddy comedy. But Wright, as usual, isn’t content to stay in just one lane. Instead, the film quickly and spasmodically leaps around in other crime subgenres, even as Wright’s camera jumps hyperactively from cut to overly dramatic cut. Sandford becomes the setting for a Miss Marple-esque small-town murder spree (Marple is of course referenced by name). In Agatha Christie fashion, it turns out that everyone has done it—at which point the film takes another bizarre left turn into a Point Break/Bad Boys apocalyptic shoot ’em up, complete with slow-mo John Woo references and little old ladies pulling firepower out of their bicycle baskets.

Buy the Book

Trouble the Saints

Hot Fuzz is obviously a love letter to the police genre; a mash-up of tropes and in-jokes chopped up and tossed into the cuisinart of Wright’s kinetic style, where intense close-ups of pints are given the same visceral weight as a woman being stabbed in the throat with garden shears. It’s for fans—but it does such cheerful violence to the genre that it’s also for anti-fans.

If cop shows irritate you, Hot Fuzz, eyes narrow behind its sunglasses, has your back. Police tropes are thumped together so vigorously that they start to disintegrate—in particular, the whole idea that police provide needed, valuable social order takes an escalating barrage of incoming fire.

Angel’s grim commitment to the law leads him to irritate first his London colleagues, and then everyone in Sandford, as he insists on arresting underage drinkers and other petty offenders, priggishly filling up jail cells to the annoyance of police and public alike. His dedication to duty involves obsessively watching completely normal people and spinning wild delusions about their violent anti-social tendencies—why is that elderly guy wearing a heavy coat?! Is he hiding…a gun?! Being an excellent police officer means endless paranoid surveillance in the interest of bothering everyone for no reason. One nice old lady even calls him “fascist!”—or is she just filling in her crossword puzzle?

Of course, all of Angel’s fears turn out to be all too true… But the movie reveals this in a way which makes law enforcement’s passion for social order look even more invidious. The local Neighborhood Watch Alliance (NWA), led by Danny’s dad, Police Chief Frank Butterman, turns out to be a collective of psychopaths dedicated to ensuring that Sandford wins best town of the year every year, no matter what. They murder the local reporter because his penchant for misspelling makes the town look bad; they murder the local gardener because she’s moving and they don’t want any other town to benefit from her green thumb. They murder a living statue for being a public nuisance. The drive for cleanliness and order is a drive for homicidal purity. In a wild-eyed monologue, Chief Butterman slurs Roma people and presciently foreshadows the 2016 presidential campaign, vowing to “make Sandford great again” as the NWA echoes empty ghostly choruses about the “greater good.”

Chief Butterman also tells Nicholas, “I was like you once. I believed in the immutable word of the law.” The thing is, he’s still like Nicholas. Both are cops to the core, policing deviance with excessive industriousness. Confronted with the NWA’s rabid assault on deviants and “crusty jugglers,” Nicholas doesn’t exactly reconsider his own rigid commitment to law enforcement. Instead, he doubles down, loading up on guns, grabbing a horse, and (with copious Sergio Leone references) bringing rough violent justice to Sandford.

Black Lives Matter and #MeToo, in different ways, have revealed the violent excesses of policing in a culture which has failed to protect women from sexual violence even as it murders innocent black people. Yet heroic police are as ubiquitous in pop culture as ever. Police are so central in our collective consciousness, in fact, that it’s difficult to imagine a world without them. Wright’s film winkingly acknowledges as much. Angel goes to a place where police aren’t necessary. But instead of just retiring the officers and telling a story about someone else, the movie experiences a kind of psychotic genre break, in which murder and escalating mayhem explode and careen and jump cut across the screen, in a desperate effort to make policing relevant again.

The movie’s climax (or, one of them anyway) is set in a model village, where Angel fights supermarket owner Simon Skinner, played with demonic insinuation by Timothy Dalton. The two men crash, stomp, and bash their way among the waist-high buildings like monsters in Mega-Tokyo, until Skinner is finally impaled by a church steeple through his mouth (“Owwww!…this…really…hurts!” he gargles and gasps.)

The scene is one of Wright’s most characteristic and most preposterous; a giddy celebration of genre which is also a giddy evacuation of genre. The cops are simultaneously larger and smaller than life, movie stars and cardboard cutouts of movie stars.. As they thrash around in a transparently fake, and miniaturized, set, sprayed by streams of fake rainwater which reference the sprays that create fake rainwater for movies, the antagonists can’t help but make you aware that the whole conflict, and the cops themselves, are a flat façade, flickering images on a screen. “Get! Out! Of! My! Village!” Skinner rants as he brutally beats Angel. “It’s not your village any more!” Angel roars back. But the joke is that the village isn’t even a village. It’s movie magic; it’s genre; it’s pretend.

Hot Fuzz identifies the violence, cruelty, paranoia, and fascism of policing—and then it imagines a world in which the police are cartoon characters thwarting chamber of commerce cults by engaging in blaring gun battles in supermarket aisles. Sandford is initially presented as a utopia because it is crimeless and perfectly ordered. But in reality, it’s a utopia because the police in it are so flamboyantly unreal.

Noah Berlatsky is the author of Wonder Woman: Bondage and Feminism in the Marston/Peter Comics (Rutgers University Press).