Beginning in 2006, acclaimed comic scribe/chaos magician/occasional fictional character Grant Morrison embarked on an epic and ambitious Batman story that would take nearly seven years across several different comic book titles to complete. As with much of Morrison’s work, his extended run on Batman was full of several recurring motifs, but perhaps the most interesting throughline in this story has been the constant presence of Bat-analogs – wannabes and replacements, heroes who, by will or requirement, have attempted to become the Dark Knight themselves, and villains who have aspired to supplant him. Morrison uses this device to deconstruct the identity of the Dark Knight and explore precisely what it is that makes Bruce Wayne tick. What does he have that other heroes don’t? Why does this man of all people get to be the Batman?

(Besides the fact that he’s a fictional character and that’s just what the way it is, because as anyone who’s familiar with Morrison’s body of work can tell you, just because something’s fictional doesn’t mean it’s not real.)

SPOILERS ahead for Morrison’s Batman run.

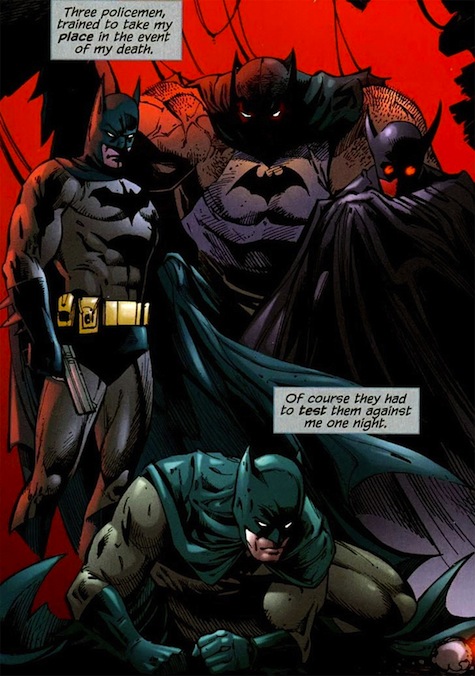

The Three Ghosts of Batman

Morrison’s first issue of Batman, #655, opens with a fairly stereotypical scene of Joker (complete with his Jokercopter!) doing something vaguely diabolical with laughing gas, but the reader is almost immediately thrown for a loop when Batman suddenly appears to save the day – only to utter the words “Die,” like a hackweight action movie hero, and shoot the Joker point-blank in the face with a pistol. Wait what? Don’t worry, we soon learn that this was not the Dark Knight himself, whom we all know has famously sworn off guns after what they did to his parents. Instead, our gunman was a rogue cop in a Batman costume, and the first of three “ghosts” that he encounters over the course of the series. As it turns out, these “ghosts” are three Gotham City policemen (that’s important – policemen, not vigilantes) who volunteered to undergo extreme psychological conditioning to replace the Batman, should the need ever arise. You know, just in case.

Each of the three replacement Batmen amplifies a quality of our own Dark Knight – and none of them can quite live up to his standard (aside from the fact that they’re all deranged bad guys). The First Man uses a gun to stop the Joker, an act which only succeeds in making him angry (and possibly crazier). The Second Man is the ultimate assertion of Batman as “alpha male,” and bears a striking resemblance to Bane, another Bat-foil. (He even goes as far as trying to break Batman’s back.) Whereas Bruce Wayne tends to engage himself in brief, shallow relationships with women to maintain his “playboy” image, the Second Man does the same, but with prostitutes, and Batman ultimately overcomes him with the power of his testosterone – literally, thanks to Bruce Wayne’s unlaundered undershirts, reiterating the importance of Bruce himself.

Finally, we meet the Third Man, whose wife and children were brutally sacrificed by Satanic cultists. According to Dr. Simon Hurt, the psychologist in charge of these experiments-gone-awry (more on him later), “We’ve studied the footage, modeled his body language and mannerisms, and come to a very simple conclusion: trauma. Shattering trauma is the driving force behind the enigma of Batman.” While the Third Man comes closest to overcoming our hero (even stopping his heart for a few seconds), it’s still not enough to truly replace the Batman. Because the Batman didn’t lose his wife and children as a grown man; he lost his parents and his innocence when he was still a child.

The Batmen of All Nations / The International Club of Heroes

Originally introduced in 1955 in Detective Comics #215 and quickly relegated to obscurity, the International Club of Heroes consists of several stereotypically ethnic Batman ripoffs. When Grant Morrison re-introduces them in The Black Glove storyline, he establishes each of them as their own unique and fleshed out personalities, complete with their own Joker-esque arch-nemeses. Of course, none of their enemies are quite as insane as the Joker, and perhaps as a result, none of them are quite as effective as the Batman himself. England’s Knight & Squire are legacy heroes, more in the vein of The Flash, The Musketeer went temporarily insane after killing a man and has since become a braggart, The Legionary of Rome has become a glutton, the Native American Man-of-Bats and his sidekick, Little Raven, are actually biological father and son, The Ranger from Australian has recently attempted to recreate himself as “Dark” Ranger, and though perhaps the most effective of the group, Argentina’s El Gaucho is still a hothead.

Originally introduced in 1955 in Detective Comics #215 and quickly relegated to obscurity, the International Club of Heroes consists of several stereotypically ethnic Batman ripoffs. When Grant Morrison re-introduces them in The Black Glove storyline, he establishes each of them as their own unique and fleshed out personalities, complete with their own Joker-esque arch-nemeses. Of course, none of their enemies are quite as insane as the Joker, and perhaps as a result, none of them are quite as effective as the Batman himself. England’s Knight & Squire are legacy heroes, more in the vein of The Flash, The Musketeer went temporarily insane after killing a man and has since become a braggart, The Legionary of Rome has become a glutton, the Native American Man-of-Bats and his sidekick, Little Raven, are actually biological father and son, The Ranger from Australian has recently attempted to recreate himself as “Dark” Ranger, and though perhaps the most effective of the group, Argentina’s El Gaucho is still a hothead.

While they have certainly established themselves as heroes within their own rights (and later join the ranks of Batman, Incorporated), each of the Batmen of All Nations is still missing that certain something that makes the Batman what he is. As Man-Of-Bats observes, “When you’re a kid, ALL adults can seem like superheroes, but they’re just people…only a little KID would ever think we were heroes.” This emphasis on childhood further reiterates the major difference between Bruce Wayne and the Batmen of All Nations: childhood trauma. Unlike these international heroes, Batman was created when he was still a child, a detail which helps him to perpetuate his own mythology as a superhero in a way that none of the other heroes can quite replicate.

While they have certainly established themselves as heroes within their own rights (and later join the ranks of Batman, Incorporated), each of the Batmen of All Nations is still missing that certain something that makes the Batman what he is. As Man-Of-Bats observes, “When you’re a kid, ALL adults can seem like superheroes, but they’re just people…only a little KID would ever think we were heroes.” This emphasis on childhood further reiterates the major difference between Bruce Wayne and the Batmen of All Nations: childhood trauma. Unlike these international heroes, Batman was created when he was still a child, a detail which helps him to perpetuate his own mythology as a superhero in a way that none of the other heroes can quite replicate.

“Paging Dr. Freud!”

As part of his mission statement coming onto the Batman franchise, Morrison attempted to find a way to reconcile every story since 1939 into a single continuity; in a diegetic sense, every Batman story that’s ever been written actually happened to a single person in the course of his lifetime. Of course, this ambitious goal required Morrison to make even the most ridiculous Batman stories somehow relevant – even stories as absurd as “Batman: The Superman of Planet X” and “Batman Meets Bat-Mite,” both from the late ‘50s. What’s more impressive is the fact that Morrison was able to find clever ways make these colorful, seemingly corny pulp tales somehow mesh with the established grim, gritty, Frank Miller-inspired Batman of today.

The “Batman of Zur En Arrh” original appeared in Batman #113 as Tlano, an alien from the Planet X, who abducts the Batman of Earth in order to help save his planet. He wears a brightly colored version of the traditional Batman costume, with a red bodysuit, yellow sleeves, and a purple cape & cowl. It’s…tacky, to say the least. Later, during the Batman RIP storyline, the evil Simon Hurt finds a way to attack Batman’s mind using the post-hypnotic suggestion phrase “Zur En Arrh,” hidden in background graffiti throughout the earlier chapters of the story. Unfortunately for him, this backfires, and the Batman of Zur En Arrh appears anew, now revealed as what is essentially a back-up personality, put in place by Bruce Wayne in the off chance that his mind itself should come under attack. The Batman of Zur En Arrh is described as Batman minus Bruce Wayne – essentially, the pure id of Batman, reverting him to a primal, almost childlike state. We learn at the end of Batman RIP that the phrase “Zur En Arrh” is derived from the last words that Bruce’s father spoke to him, in the alleyway outside of the theatre before the mugging that took his life: “I’m not so sure Gotham City would welcome a masked man taking the law into his own hands, Bruce. The sad thing is, they’d probably throw someone like Zorro in Arkham.”

When the Batman of Zur En Arrh emerges, he is also accompanied by Bat-Mite, an imp-like version of the Batman who helps guide the primal Batman of Zur En Arrh towards his destination. “I’m the last fading echo of the voice of reason, Batman,” he explains. Bat-Mite makes an earlier cameo in Morrison’s run during a dream/hallucination sequence at the funeral of Thomas and Martha Wayne. “The dark ain’t so bad when you learn how to make friends with it,” he tells a young, mourning Bruce at his parents graveside. Looking at Bat-Mite in terms of his relationship to the Batman of Zur En Arrh, it becomes clear that he is a hallucination of Bruce’s childhood – an imaginary friend that exists within Bruce’s self-conscious, a childish conscience to help guide him when all else fails (or when the Batman of Zur En Arrh consumes the id, for example). “I’ve read how traumatized children sometimes develop cover personalities to protect themselves from painful repressed memories,” Bruce explains in a flashback, and it seems this might be the key to Batman’s unique abilities as a hero.

The New Robin

The New Robin

At the start of his run, Morrison also introduces us to Damian Wayne, the illegitimate son of Bruce and Talia al Ghul. Bruce has of course had several surrogate “sons” throughout his life, mostly in the form of the various Robins that he’s taken on as sidekicks, but Damian is different; he’s actually Bruce’s flesh and blood (and a sociopath to boot). While Bruce’s relationship with previous Robins is often interpreted as an attempt by him to reclaim or salvage his own damaged childhood, forcing him to care for the biological son that he never knew he had flips this established relationship on its head and sheds new light on the recurring thematic traditions of orphans and sons that have shaped the Batman mythos. Whereas the crimefighting millionaire may have seemed a cool surrogate father for Dick Grayson and Tim Drake, he plays a much more authoritarian patriarchal role with his own son (which is especially interesting considering that Bruce did not get to grow up with his own father). Although Damian was raised by his mother, he makes the conscious decision following his father’s “death” in the Batman RIP story to become a hero as well, and eventually goes on to become the new Robin and help continue his father’s legacy – not unlike Bruce himself.

We’re also treated to several glimpses into the near future during Morrison’s run, where we get to see Damian take on his father’s mantle after his death. When this concept is first introduced in Batman #666, we see Damian kneeling in an alleyway by Bruce’s dead body, a visual that harkens back to the iconic image of young Bruce kneeling in his own parents’ blood. We also see Damian “cheating” and breaking several of the crimefighting rules established by his father—using deadly explosives, for example—in order to compensate for the fact that he sees himself as “not being good enough.”

While it can be difficult for any son to believe that he has satisfactorily lived up to his father’s expectations, Damian should naturally have the upper hand. Unlike his father, who was driven to train himself to peak physical condition, Damian is already a genetically enhanced perfect biological specimen. But perhaps that’s the point: Bruce was driven by childhood tragedy to make something of himself, while Damian is missing this motivating factor, and no scientific tampering can compensate for this (although Talia does eventually disown him and cast him out in Batman & Robin, so he does eventually lose both his mother and father, just like Bruce).

Batman & Robin

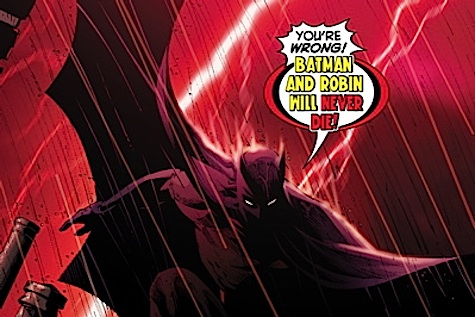

Later in the run, Dick Grayson also takes on the mantle of the Batman with Damian as his Robin. While Dick has established himself as an efficient crimefighter in his own right, he understands that the symbol of the Bat is bigger than just Bruce, and it cannot be allowed to die. Dick does an excellent job temporarily filling Bruce’s shoes (or cowl, as it were), and even the police recognize that Batman is different, but they accept it, as he’s still necessary. “Didn’t he used to be taller… Batman sounded different, right?” an officer asks Jim Gordon, who responds, “Different maybe, but familiar.”

Perhaps Dick’s success in replacing Bruce as Batman has to do with the similarity of his origins – his parents were also murdered in cold blood when he was a boy, although he was older than Bruce was. The main difference between them is that Dick had Bruce to take care of him and protect him from the dark, vengeful, brooding places that Bruce has seen. This is reflected in Dick’s upbeat demeanor, which he upholds even when filling the role of Batman. This makes an interesting inversion of the established Batman-Robin relationship (which Dick of course originated) – with Dick and Damian, Batman is the cheerful, friendly part of the duo and Robin is dark and brooding.

The Hole In Things

Batman’s greatest enemy (besides the Joker) is evil. This may sound like a stupidly obvious statement, but Grant Morrison took this idea and made it literal during his run on Batman, pitting the Dark Knight against Darkseid, the New God embodiment of evil, and Dr. Simon Hurt, who is for all intents and purposes the Devil himself in the form of a disinherited member of the Wayne family. “What we are about to do will be a work of art. Nothing less than the complete and utter ruination of a noble human spirit,” announces Hurt at the beginning of Batman RIP (although by this point we’re aware that he’s been pulling the strings for quite some time).

There’s a long-standing literary tradition of the Devil trying to corrupt or destroy noble souls, and a soul as good as Batman’s would certainly be considered the grand prize. And how does Hurt plan on destroying the goodness of the Batman? The first step is to undo the tragedy of his origins. To accomplish this, Hurt appears in public and claims to be Bruce’s father, Thomas Wayne, whose death was faked, and proceeds to sully the Wayne’s good reputation in Gotham City by spreading rumors and false evidence of drug addictions, scandals, and an illicit affair between Martha and the good butler Alfred. In the case that this was all true—that Thomas Wayne was still alive, and that the Waynes themselves were not the upstanding philanthropic citizens they were believed to be—it would call into question the entire purpose of Batman’s existence, thus destroying the goodness of his soul.

(It should be noted that technically speaking, Hurt’s name actually is Thomas Wayne, except he was born hundreds of years earlier in the Wayne family tree and was consequently made immortal by Darkseid’s Hyperadapter in the form of a bat because comics.)

(It should be noted that technically speaking, Hurt’s name actually is Thomas Wayne, except he was born hundreds of years earlier in the Wayne family tree and was consequently made immortal by Darkseid’s Hyperadapter in the form of a bat because comics.)

Of course, Hurt’s claim that he is the “father” of Batman is not entirely untrue either, if we consider that Batman is the byproduct of pure evil in the form of cold-blooded murder (which harkens back to Cain and Abel, and there’s also a whole “brothers” motif going on with Hurt and Batman, but that’s a topic for another time). In those terms, Batman (though not necessarily Bruce himself) was technically “spawned” by evil. When trying to rationalize his battle with Hurt, and the possibility that he may in fact be the Devil incarnate, Bruce says to himself, “If I couldn’t find a body, Hurt stayed a ghost. An empty space. Hiding where he couldn’t be found, in the gaps. The holes. The absences.” Though it might sound a bit corny when broken down this way, “the hole in things” is evil, which is essentially the hole that was left in Bruce’s heart when his parents were killed.

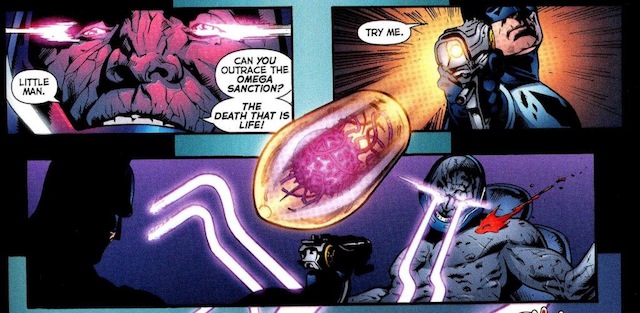

Batman’s death does not occur directly at the hands of Dr. Hurt at the end of Batman RIP, but rather by Darkseid, another embodiment of evil, during Final Crisis (also penned by Morrison). Darkseid fires a bullet backwards through time to kill his son, Orion (Sons. Bullets. Are we sensing a pattern here?), making a literal hole in his chest. Ever the detective, Batman looks at the evidence and realizes that, whether literally or metaphorically, this was the same bullet that killed his parents. “It was the blueprint, the template for every bullet there had ever been. It was the original of the bullet that killed JFK, MLK, John Lennon, Gandhi, Ferdinand, Thomas and Martha Wayne.” For Bruce, the bullet represented original sin – the purest evil, the death of his parents. Ultimately, Batman breaks his golden rule of “no guns” and shoots Darkseid with that same bullet. This creates an endless cycle: Batman was created by evil, then uses that same evil to destroy evil, which of course, created him in the first place. By taking on a God, a living symbol, Bruce succeeds in turning himself from a man into a piece of mythology – the same way that he created the Batman as a symbol, but on a larger scale. He also succeeds in being killed and sent tripping through time at the hands of Darkseid’s Omega Sanction, but we’ll save that for another section.

During his time in Darkseid’s captivity, Batman is forced to endure physical and psychological experimentation at the hands of some evil cronies, in their attempt to create an army of evil Bat-clones (much like the aforementioned Three Ghosts of Batman). Using a psychic creature called The Lump, they play and replay through the memories of Batman’s life, hoping to figure out what makes him tick, and use the raw emotional energy of those moments to fuel their evil army of clones. Each time they replay the beats of his life for him, they tweak some detail – if the bat had never flown through his window, for example, an iconic image depicted in Frank Miller’s Batman Year One. But at one point we’re told a story of a world where Bruce’s parents never died, and this seems to undo everything, leaving a successful and happy Bruce Wayne to dream of a world where there existed a person who could stop the psychotic villains that populated Gotham City, or where someone might rescue and adopt Dick Grayson, the orphaned son of a murdered circus family. Eventually, The Lump realizes that their army of evil Bat-clones will never work because that raw, emotional energy is not enough – they need the actual experiences, the trauma, all of which would of course prevent them from ever being evil. “What kind of man can turn even his life memories into a weapon?” they lament. But as Bruce says as he finally breaks free, “You can have [the memories and the trauma]. If you can handle it.”

Time and the Batman

Morrison’s The Return of Bruce Wayne miniseries sent Bruce hurtling through time and essentially creating his own mythology, setting up the most important pieces of his life starting from prehistoric times. It’s also a great example of stupidly fun high concept story pitches gone right – Pirate Batman and Caveman Batman certainly sound fun on their own, but Morrison was impressively able to use these stories to make a point and feed into his larger Batman narrative. On a very basic and literal level, this story gave us the chance to see how Bruce Wayne works outside of his element and without the mask of the Batman to hide behind (although he always seems to end up wearing black and doing something involving capes, cowls, or bats…). But we also get to see him perpetuate his own mythology – creating the original bat-shaped plans for the Wayne family mansion, inspiring the bat-worshipping Miagani tribe, and shaping his own family tree.

In Batman #700, a mostly-standalone story of a locked-room mystery set across three different times and three different Batmen (Bruce, Dick, and Damian), Joker devises a plan to send Batman back in time, “to the day, the very moment Batman was born! When Batman himself will be given one last heartbreaking chance to abort the demons that drove him to be, and thus undo his own creation!” Bruce ends up getting this chance throughout the Return of Bruce Wayne storyline (specifically in #5), but of course, he never takes it. Bruce’s ability to plan for all eventualities is at its finest during his journey through time, but at no point does he think to set up the dominoes in some way to avoid his parents’ murder, because it was this experience that shaped him into who he is. “There was never a choice,” he tells a young Dick Grayson.

Batman, Incorporated

Batman, Incorporated

Instead, Bruce remains focused on the Batman as a symbol. He realizes very early on in his career that his war on crime must be bigger than him, which is why he creates the Batman in the first place, a larger-than-life living symbol that strikes fear in villains, because as a boy, bats were the thing he was most afraid of. But at the end of The Return of Bruce Wayne he realizes that he was wrong: there was one thing that scared him more than bats, and that was being alone. While the tragedy at the root of his origin has always been the key motivating factor in his life, Bruce finally understands that he would never have come as far as he has without the help of his friends – without Alfred there to patch him up each night, or without a Robin to bring some much-needed levity into his life, etc.

And so, upon his return to the present, Bruce announces the creation of Batman, Incorporated, an international army of Batmen. “No one knows WHO Batman is anymore,” he explains. “Or how MANY there are! Batman is EVERYWHERE, and if he didn’t exist, I guess we’d just have to invent him.” But even as Bruce travels around the globe building his army (including the previously mentioned Batmen of All Nations), Morrison highlights the slight differences in the lesser heroes that he recruits to become his new Batmen, and in turn, Bruce begins to shape them in his own more efficient image. We see Mr. Unknown, the Batman of Japan, using a gun to seek his vengeance, something that Bruce puts an immediate stop to. El Gaucho from Argentina even mimics Bruce Wayne’s playboy lifestyle secret identity (and refuses to believe that Bruce is actually Batman). Man-Of-Bats is a philanthropic doctor, but he has no secret identity, and his crimefighting turf is mostly insular and kept within the borders of his reservation (plus his crime lab has its own variations on the Penny and T-Rex seen in the Batcave). While each efficient (read: Batman ripoff) heroes in their own rights, this demonstrates the uniqueness of Bruce Wayne, and why those qualities define him and make him into the Dark Knight that we all know and love.

(We also see Bruce simultaneously controlling two separate cybernetic avatars in the Waynetech Internet 3.0 world of Batman, Incorporated #8, which proves not only Bruce’s unique efficiency as a hero, but further perpetuates the mystery surrounding the symbol of the Batman, as no one knew who was actually controlling the Batman avatar.)

At the beginning of the Batman RIP storyline, Bruce allows his girlfriend, Jezabel Jet, into his world as Batman, and she makes a profound observation when he first brings her into the Batcave: “It was so brave of you, Bruce, so ingenious, to make yourself into the great dark knight who wasn’t there for you when you needed him. But all this…is a disturbed little boy’s response to his parents’ death.” Despite the fact that we later learn of Jezabel’s insiduous intentions (the fact that Bruce is only ever interested in evil/dangerous women is a topic for another time), this idea has been central to Morrison’s exploration of the Batman mythos, as demonstrated by the multitudes of analog, replacement, and wannabe Batmen.

While Batman is hardly the only superhero with a defining tragedy in his life, Bruce Wayne’s circumstances were incredibly unique, and this is what has made Bruce in particular into such a strong crimefighter and character, even without that iconic cape and cowl. There’s more to him than a freak accident (The Flash), some tragic adolescent mistake (Spider-Man), or being the last son of a dying alien race (The Doctor/Martian Manhunter/Superman). As of this writing, Morrison’s Bat-opus is moving into its final act, pitting Batman, Incorporated against Talia al Ghul’s Leviathan organization (which, in a sick inversion of Batman’s own origin, uses children as soldiers by forcing them to kill their own parents). But even without reading the ending of this epic, 7-year-long tale, Morrison has made his case quite clear for what it is about the Batman that makes him so unique and, frankly, awesome. Not that anyone needed another reason to respect, fear, and adore the Batman, but no one’s ever explored his distinct greatness in quite the same way.

Thom Dunn is a Boston-based writer, musician, homebrewer, and new media artist. He enjoys Oxford commas, metaphysics, and romantic clichés (especially when they involve whiskey and/or robots). He firmly believes that Journey’s “Don’t Stop Believing” is the single worst atrocity committed against mankind. Find out more at thomdunn.net.