One of the great pleasures of historical fiction is comparing how authors make different stories out of the same events. The Wars of The Roses (~1455 to 1487) furnish enough political twists, abrupt betrayals, implausible alliances, and mysterious deaths to weave into dozens of different accounts if storytellers (historians, novelists, or playwrights) make clever decisions when guessing or inserting motives. The historical record tells us what Person A did on X date, but our only accounts of why are biased and incomplete, and rating historical bias on a scale of 1 to 10, chroniclers from the period get a rating of “lives-around-the-corner-from-the-Royal-Headsman.” The what is fixed, but the why can have a thousand variations.

2016 will see the long-awaited second season of The Hollow Crown, a new BBC film series of Shakespeare’s histories, whose second season will cover the Wars of the Roses. That makes this a perfect moment to compare Shakespeare’s version with another recent television dramatization of the same events, The White Queen, adapted from Philippa Gregory’s Cousins’ War Series. In fact, I want to compare three versions of the Wars of the Roses. No, I don’t mean Game of Thrones, though it is a version in its way, and both The White Queen and Shakespeare’s versions are great ways to get your Game of Thrones fix if you need it. My three are: (1) The White Queen, (2) the second half of Shakespeare’s Henriad history sequence (Henry VI Parts 1, 2 and 3 plus Richard III), and (3) the most ubiquitous version by far, Richard III performed by itself.

A moment of full disclosure: I have watched Shakespeare’s Henriad sixty-jillion times. Well, perhaps only eleven times all the way through, but given that, unabridged, it’s more than 20 hours long, I believe that merits the suffix -jillion. For those less familiar, Shakespeare’s “Henriad” history sequence is made up of eight consecutive plays, which cover the tumults of the English crown from roughly 1377 to 1485. (Often “Henriad” means just the first four, but for the moment I find it easiest as shorthand for the set of eight.) While many of the plays, especially Henry V and Richard III are masterpieces on their own, it’s exponentially more powerful when you have it all in sequence; just think of the amount of character development Shakespeare gives Lady Macbeth in eight scenes, then imagine what he can do with 20 hours. (For those interested in watching the Henriad in the raw, I’ll list some DVD sources at the end.) In many ways, the Henriad can be thought of as the first long-form historical drama, a Renaissance equivalent of The Tudors or The Borgias, and a model which has shaped long-form drama ever since.

Formally “Henriad” is usually used for the first and more popular half of the sequence, which consists of Richard II, Henry IV parts 1 and 2 and Henry V, which the BBC adapted in 2012 as the first season of The Hollow Crown, a version packed with fan favorites including Ben Whishaw as Richard II, Simon Russell Beale as Fallstaff, Michelle Dockery as Kate Percy, Jeremy Irons as Henry IV, and Tom Hiddleston as Henry V. The second half—the Wars of the Roses half—consists of Henry VI Parts 1, 2, and 3 (three separate plays), and Richard III. This time the BBC has again worked hard to pack it with big names, including Hugh Bonneville as Duke Humphrey of Gloucester and Benedict Cumberbatch as Richard III, as well as Tom Sturridge as Henry VI, Stanley Townsend as Warwick, and, most exciting for me, Sophie Okonedo as Margaret of Anjou, one of the most epic roles in the history of theater, who, in my favorite filmed version of Henry VI Part 2, Act III scene ii, routinely makes me go from sick-to-my-stomach at her vileness to actually weeping in sympathy with her in—I timed it—8 minutes!

The White Queen TV series covers events equivalent to most of of Henry VI part 3 plus Richard III, i.e. the last quarter of the eight-play sequence, or half of what will be The Hollow Crown Season 2. If The White Queen is half of the later Henriad, Richard III by itself is half of The White Queen. Comparing all three versions demonstrates how choosing different start and endpoints for a drama can make the same character decisions to feel completely different. I will discuss the TV version of The White Queen here, not the novels, because what I want to focus on is pacing. With filmed productions I can directly compare the effects of pacing, not only of the historical starting points and endpoints chosen by each author, but also minute-by-minute how much time each dramatization gives each character, event, and major decision, and how the different allocations of time affect the viewer’s reactions to the same historical events.

To give a very general overview of the relationship between Philippa Gregory’s presentation of the events and Shakespeare’s, Gregory’s version is squarely in the camp (with most historians) of reading Shakespeare’s Richard III as a work of extremely biased propaganda, anti-Richard and pro-the-Tudors-who-overthrew-Richard-and-now-employ-the-Royal-Headsman. But Gregory’s version reverses more than that; in fact, if you graphed all the characters in the Henriad by how good/bad they are and how much the audience sympathizes with them, ranked from 10 (Awww…) to -10 (Die already!), to get their The White Queen counterparts you pretty-much just need to swap the positive and negative signs; the worse they are in Shakespeare the more we feel for them in The White Queen and vice versa, transforming villains to heroes and heroes to villains, and the most sympathetic characters to the least sympathetic (which, with Richard around, is not the same as simply flipping good and evil). Gregory’s version also focuses on the women, giving robust extended parts to Edward’s queen Elizabeth, as well as to Anne Neville, and to Margaret Beaufort, the mother of Henry Tudor (not to be confused with Margaret of Anjou, the biggest female role in Shakespeare’s version).

SPOILER POLICY: since in a historical dramatization events are facts, while character motives and feelings are the original parts invented by the author, I will discuss historical facts freely, and Shakespeare’s ubiquitous versions freely, but I will, whenever possible, avoid spoiling the original character motivations invented by Philippa Gregory for her version, and I will also avoid giving away The White Queen‘s answers to the historical who-done-its, since whenever someone dies mysteriously in the Tower, it’s up to the author to choose a culprit. If you are unfamiliar with the events of the Wars of the Roses, and you want to watch The White Queen or read the Cousins’ War Series and be in genuine suspense as to who will win, lose, marry, or wear the crown, you should stop reading this now, but I think it’s even more fun to experience the fiction already knowing what has to happen, and enjoying the author-intended meta-narrative suspense of, “I know Character A has to die soon, but will it be illness or murder?”

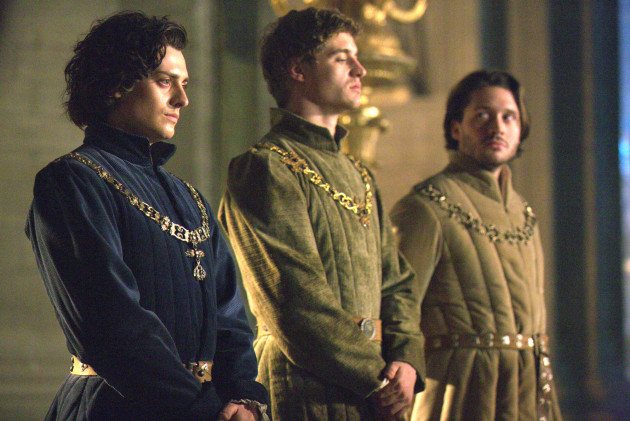

George, Duke of Clarence

OK, start and endpoints, and pacing. Let’s look first at a small case, George Plantaganet, 1st Duke of Clarence.

We know George best from Richard III, which begins with guards marching George to the Tower. In a touching scene, George’s younger brother Richard vows to prove George’s innocence and save him, after which Richard tells us in secret that (wahaha!) he has plotted all this to arrange George’s death and clear his own path to the throne (wahaha hahaha!). The arrest is history, the wahahas are Shakespeare. History then binds Shakespeare (and any author) to have George of Clarence die in the Tower at his brother Edward’s order, and to make some nod to the rumor—famous at the time—that George was downed in a vat of Malmsey wine.

George’s death (Act 1, Scene iv) is one of the most famous and powerful scenes in Richard III, in which the terrified and repentant Duke first recounts a terrible dream prefiguring his drowning and descent to Hell, and reviews with horror the broken vows which weigh upon his conscience, vows he broke to help win the throne for his brother, who now threatens him with execution. Enter The Two Murderers (actual stage direction) who find the Duke so virtuous and persuasive that they can barely force themselves to do what one of them, contrite and blood-smeared, calls “A bloody deed, and desperately dispatched.”

This scene is often staged in ways that make great use of meta-narrative tension, knowing that we the audience (like Shakespeare’s original audience) know this history, and know what has to happen. I saw a delightful standalone Richard III at the National in 2014 (Jamie Lloyd’s production with Martin Freeman) set in 1969, which kicked off the Death of the Duke of Clarence by wheeling a fishtank onto the set. Instantly we realize they must drown Clarence in the fishtank. The certainty of that ending is so intensely distracting that the whole time Clarence pleaded with the murderers, it kept repeating in my mind, “They’re going to drown him in the fishtank… They’re going to drown him in the fishtank… Drown him in the fishtank… Drown him in the fishtank! Drown him in the fishtank!!!” until without intending it I found myself rooting inside for it to happen, rooting for the narrative conclusion, despite how horrible it was.

The staging itself, and knowledge of what must happen, draws the audience into complicity, just like Richard’s charismatic villain speeches. And then they drowned him in the fishtank. But then the Two Murderers froze, as did I. “Wait!” I thought. “Now Second Murderer has to say ‘A bloody deed, and desperately dispatched.’ But there’s no blood! Usually they stab George and then drown him offstage. This is a production so bloody they’ve handed out ponchos to the first two rows, how are they…?” And then one Murderer reached down and slit George’s throat, and blood red spread through the water like the afterimage of a shark attack. And then with deep satisfaction: “A bloody deed, and desperately dispatched,” and suddenly the audience shares Second Murderer’s feelings of guilt at having been complicit—deep inside—with such a terrible deed.

A staging like Jamie Lloyd’s helps bring power to Clarence’s death scene, which helps differentiate it from the many other executions of major nobles whom the viewer is going to spend the next hour struggling to keep straight. Shakespeare is wonderful at making characters vivid and appealing over the course of a single quick speech, but it remains difficult for the audience to feel too much about the death of George since we did just meet him, and the first thing we heard about him was that he was going to his death.

Clarence: Changing the Starting Point

But what if, instead of watching Richard III alone, we’ve just watched the three parts of Henry VI as well? George first appeared in the end of Henry VI Part 2, fighting alongside his two brothers to help their firebrand father the Duke of York seize the throne (though this is Shakespeare fudging, since George was actually too young to fight at the time). This is the final stage of the grueling sequence of destruction in which we have watched wretched England degenerate from its happiest hour under the incomparable Henry V (mandatory fanfare when we speak his name) through a series of feuds, betrayals, and bloody civil broils as chivalry has died and selfish ambition half burned London to the ground. Twice. Clarence took part in all that, and Shakespeare, and Philippa Gregory too, are locked into these events, but have carte blanche to invent Clarence’s motives. After the death of his father the Duke of York—who almost succeeded in taking the throne from Henry VI—Clarence (though too young to be a major combatant) was with the faction helping put his brother Edward on the throne, spearheaded by the famous “Kingmaker” Earl of Warwick. Then Edward suddenly and controversially married the young and not-very-noble widow Elizabeth Woodville, spurning a match Warwick had arranged with a French princess in the process. Warwick and Clarence then broke with Edward and started fighting for Henry VI, with support from the irate French King.

That much is fixed, but look at what different pacing can make of it:

In Shakespeare’s version the events are quick. As soon as Edward is crowned he destroys the peace his allies (including a fictionally older-and-able-to-fight George fought so hard for) by spurning the French princess thereby alienating France and the “Kingmaker” Earl of Warwick—who had pawned his honor on the match—causing France and Warwick to throw their strength behind deposing Edward and reinstating Henry, all for a woman (ducal facepalm!). Edward has also been showering valuable positions and marriage alliances on his new wife’s family, saving none for his brothers. A frustrated George of Clarence decides to go seek the hand of a daughter of the mighty (and honorable) Warwick (keep careful track of the order of events here) who has already broken with Edward to support Henry. Warwick and his anti-Edward allies are skeptical that Clarence will stay true to them against his own brother, so they not only have George marry Warwick’s daughter, but they have him take an oath—in front of everyone, in a cathedral, upon the sacrament—to remain loyal to Henry and Warwick until death. Clarence takes this most sacred vow, but, when the final battle is about to begin, and the two brothers face each other across the battlefield, Edward pleads with Clarence, invoking filial love and childhood friendship, and Clarence suddenly changes his mind and fights on his brother’s side, breaking his mighty oath. Clarence (in Shakespeare’s version) even helped Edward kill Henry VI’s son Edward Prince of Wales, wetting his hands with the blood of the very prince to whom he had pledged his loyalty, all for Edward’s sake.

Moving forward from this to Richard III, George of Clarence’s death in the Tower is now much more complex. This wasn’t a small broken oath the terrified Clarence had on his conscience, it was a super-mega-maximum-strength oathbreaking, the kind Shakespeare’s audience knows is not redeemable by simple repentance, and would indeed make the ghosts in Hell eager for George’s arrival, “Clarence is come! False, fleeting, perjured Clarence!” (I, iv). George’s death now feels, not like a simple act of villainy, but like a complex mixture of justice and injustice, since he is innocent of treason against his brother Edward but guilty of treason against the other Edward, son of Henry VI, and of generally increasing the violence and bloodshed of the Wars of the Roses, costing many lives. Injustice on the immediate scale is justice on the Providential scale. And we gain all this just by moving our starting point.

Clarence: Changing the Pacing

The White Queen television series starts our knowledge of Clarence slightly later than Henry VI, leaving out the period before Edward is crowned, but it makes everything different, transforming George of Clarence from Shakespeare’s eloquent, repentant, terrified soul who died in the Tower to a radically different figure—much more scheming and far, far more negative—a transformation achieved largely through pacing, allotting several hours instead of a few minutes to the process of George’s break with Edward. Watch how this summary changes things without me having to describe any of George’s motives, words or facial expressions as the events unfold:

King Edward IV marries Elizabeth, angering Warwick and spurning the French princess. Clarence then marries Warwick’s daughter, knowing Warwick is angry at Edward. Warwick then attempts to overthrow Edward IV and make Clarence king, which will make his daughter Queen and give him (presumably) a more compliant King. (Note how Shakespeare entirely skipped this phase of Clarence trying to take the throne, something widely alleged at the time). Early attempts go badly, and Clarence winds up exiled in France labeled a traitor (this, too, Shakespeare blurs out). After losing several other allies, Warwick gives up on replacing Edward with Clarence, and allies with France and with Henry VI’s exiled wife Queen Margaret and her son Edward (the Truly Horrid) Prince of Wales. Warwick asks Clarence to join him and promises to at least restore Clarence from a life of exile to his Ducal title. At the same time, Clarence receives messages from Edward asking him to betray Warwick and promising power and wealth if he returns to Edward’s side. George has many weeks to consider and plan his betrayal of Warwick (not five minutes of brotherly love rekindled across the battlefield), and eventually carries out this premeditated betrayal. Several more twists and schemes later, Edward finally has Clarence arrested for treason (after forgiving it at least three times!) and sent to the Tower.

None of this is character, it’s reorganization of fact. Decompressing time, and reinserting events which were alleged at the time but omitted by Shakespeare, has transformed a stained but repentant Clarence into an ambitious, selfish, and negative Clarence. His treason was real, and his oathbreaking and betrayal of Warwick was a calculated decision, not an act of sudden love. Philippa Gregory and the TV writing team could have fit a range of different personalities to this sequence of betrayals—from charismatic villain to worthless scumbag and many options in between—but it could not be Shakespeare’s Clarence, just by virtue of which facts are included, excluded, or blurred in each retelling.

Compressing Time: What Kind of “Kingmaker” is Warwick?

Shakespeare does a lot of compressing time, often with results which decrease historical “accuracy” but increase drama. My favorite example (and the most absurd) is in Shakespeare’s infamously least-respected play, King John. Here Shakespeare so compresses a peace between France and England, sealed by a royal marriage, that, instead of lasting a few years (short for a peace), the ambassador from Rome comes to destroy the peace while Princess Blanche is still standing in the aisle having just said “I do,” leading to a brilliant speech which boils down to “I’ve been married for precisely three minutes and now my father and husband are at war!”

Shakespeare uses this to great effect in his retelling of the Wars of the Roses at many points, squeezing events in ways which completely recast people. Clarence is one example. Another, even more vivid and intense, is the “Kingmaker” Earl of Warwick, where changes in pacing and the start- and endpoints again make the version in The White Queen a completely different archetype from Shakespeare’s.

In The White Queen TV series we meet Warwick first after he has successfully planted Edward on the throne. He is introduced by the nickname “Kingmaker” and we see his explosive irritation as Edward refuses to be ruled by him and insists on marrying Elizabeth. Since the audience’s sympathy is with Elizabeth primarily—and her passionate romance with Edward—this Warwick comes across as an enemy of true love, and as a selfish political schemer, deeply intellectual, who wants to be the mind behind the throne. Nothing is said about how he got Edward the crown, but since all the actions we see him take—both in support of Edward and, later, in support of Clarence, Margaret, and Henry—are political negotiations and alliance brokering, we naturally imagine that he got Edward to the throne similarly, through savvy and guile. When he breaks with Edward to support first Clarence, then eventually Henry and Margaret—making full use of the anyone-but-Edward options—it seems like his primary motives are selfishness and ambition, and all this from what we see him do, and don’t see him do, without going into his actual personality.

Shakespeare’s Warwick begins decades earlier, when see Warwick striding in armor, a fierce, battle-scarred young veteran, of the great generals of the English armies in France, who won city after city fighting in the front lines, only to see them lost again through the weak government of Henry VI. Enter the proud young Richard Duke of York, who will later be father of our King Edward IV, and of Clarence and Richard III. Young Richard of York learns from his dying uncle Edward Mortimer that he is actually higher in the royal bloodline than Henry VI and thus is the rightful king (see long elaborate family tree). In need of help, York approaches Warwick and his father Salisbury and explains his genealogical claim (“Edward III had seven sons… uncle… niece… grand-nephew… I’m the king.”) Hearing the truth of his claim, Warwick and his father instantly kneel and swear fealty to Richard, even though he has nothing to offer them but the truth of his birthright. We then witness several heroic battles in which Warwick rages over the battlefield like the savage bear that is his crest, a true exemplar of valor, spurring on friend and foe alike in such valiant moments as, when, as the enemy retreats after an exhausting battle, York asks, “Shall we after them?” and panting Warwick cries “After them? Nay, before them if we can!” This is not a scheming politician but a knight, a “Kingmaker” in the sense that he carried York to power with his own sweat, risking his own life, taking many wounds, even losing his own father in battle. And when Richard of York is taken and slain by Margaret of Anjou, it is Warwick who drags the tearful young Edward from his grief and vows to plant him on his rightful throne. This is a Kingmaker of blood, sweat, and sacrifice, not schemes and bargains.

When Shakespeare takes us forward into the territory covered by The White Queen, he relies on time compression to make his Warwick still the brave and valiant bear. Instead of having Warwick plan for months after Edward’s unwelcome marriage, trying Clarence and only later Henry, Shakespeare compresses the entire reversal of Warwick’s allegiance to a single scene directly parallel to the scene in which the truth of birthright first won him so instantly to young York’s side. Edward has consented to marry the French Princess Bona, and sent Warwick to the Court of France, where exiled Margaret of Anjou had almost persuaded King Louis to lend her his armies to fight York. Warwick, pledging his knightly honor on the truth of his words, vows Edward’s love and faithfulness to Bona. In light of the marriage, Louis agrees to set Margaret aside and conclude a permanent peace for France and England for the first time in a generation (Thank you, Warwick! Kingmaker and Peacemaker!). The marriage is concluded, but in that very moment a messenger arrives from England to announce that Edward has thrown Bona over and married Elizabeth. Louis and Bona rise in rage, and, with the letter still in his hand, Warwick—his knightly honor shattered by Edward’s oathbreaking—declares:

King Lewis, I here protest, in sight of heaven,

And by the hope I have of heavenly bliss,

That I am clear from this misdeed of Edward’s,

No more my king, for he dishonours me,

But most himself, if he could see his shame.

Did I forget that by the house of York

My father came untimely to his death?

Did I let pass the abuse done to my niece?

Did I impale him with the regal crown?

Did I put Henry from his native right?

And am I guerdon’d at the last with shame?

Shame on himself! for my desert is honour:

And to repair my honour lost for him,

I here renounce him and return to Henry.

(To Margaret) My noble queen, let former grudges pass,

And henceforth I am thy true servitor:

I will revenge his wrong to Lady Bona,

And replant Henry in his former state.(Henry VI Part 3, Act III, scene 3)

That’s it. No arguing with Edward, no trying to put Clarence on the throne, no travel back and forth; a dishonorable and unjust sovereign is unworthy of allegiance, so in that instant the next most rightful claimant—Henry—owns his loyalty. Done. There is pride and ambition in Shakespeare’s Warwick, and even hubris, but it is the hubris of supreme knightly excellence, the tragedy of chivalry in an imperfect age. Except that if Shakespeare had stuck with the real pacing of historical events he could never had made such a character. Compression of time absolutely transforms the moral weight of events, and the viewer’s sympathies.

Who the Heck is Stanley and Why Should I Care?

One other facet of time compression that affects historical dramas—especially Shakespeare—comes from the author’s expectations of the viewer’s knowledge. There are moments in Shakespeare’s histories when people pop up without any real explanation, and suddenly we’re supposed to care about them. For example, one of the subplots of the end of Richard III involves a nobleman called Stanley, who shows up without any real introduction, and we’re supposed to be in great suspense when his son is held hostage (this after we’ve watched the vicious murders of many many more well-established characters, which makes it very hard to care about Young George “not-actually-appearing-on-stage-at-any-point” Stanley). The problem here is that we are—from Shakespeare’s perspective—time travelers. He was writing for his contemporary Elizabethan audience, one that knows who Stanley is, and who Alexander Iden is, and who Clifford is, and where they’re from, and why it matters, and which current-to-them leaders of the realm are descended from them. So when someone called Richmond appears out of nowhere at the end, Shakespeare’s audience knows why the narrative stops to fawn on him for speech after speech. Stepping back in time 400 years to watch the play, we don’t.

Modern works suffer from this problem just as much, though we usually don’t see it. Think for a moment of the musical 1776 (Sherman Edwards & Peter Stone), which dramatizes the passing of the American Declaration of Independence. Periodically over the course of 1776, arriving letters or discussions of military matters make the characters mention George Washington, making it clear he is a figure of great importance, though he never appears on stage and no one ever explains who he is. Writing for a 20th century American audience, the scriptwriter knows he doesn’t need to explain who this is. Yet, if 1776 were staged 500 years from now on Planet SpaceFrance, you could well imagine one SpaceFrench viewer turning to another, “Washington, I know that’s an important name—what did he do again?” “Not sure; let’s look him up on SpaceWikipedia.” Just so, we sit there wondering why everyone suddenly cares so much about this guy Stanley, and wishing live theater had a pause button so we can look it up.

The White Queen is written for us time travelers, and spends lavish time establishing Stanley, Richmond and the other figures who become central to the end of the Wars of the Roses but had no visible involvement in Shakespeare’s versions of the beginning. We watch young Henry Tudor (later Richmond, later King Henry VII) from the beginning, and when he comes into the narrative at the end it feels like the logical conclusion instead of Shakespeare’s Hero-Out-Of-Nowhere. The TV writing is happily not too heavy-handed with this, the way some historical dramas are, constantly lecturing us on basics like where France is, but it offers precisely the guiding hand Shakespeare doesn’t to make Medieval/Renaissance life a bit more navigable for we who are, while we trust ourselves to Shakespeare, strangers in a strange time. It also makes the end more conventionally satisfying than the end of Richard III—conventional in that it fits better into modern tropes of pacing and what constitutes a satisfying ending. Some viewers will find this more appealing, others less, but it is one of the universals of recent TV historical dramas, adapting events to fit our current narrative preferences—just as Shakespeare once adapted them to fit his.

Of course, a reflection of the Wars of the Roses written even more for time travelers is Game of Thrones, which preserves the general political and dynastic mood, and the many families vying after the overthrow of the legitimate dynasty, but invents all the families and places so we don’t need to get bogged down by our lack of knowledge of where Burgundy is, or our unfamiliarity with how much authority the papacy exerts over different bits of Europe, or our inability to keep track of all the characters named Henry, Edward, or Margaret. Shakespeare’s period drama, modern historical drama, and political fantasy drama—three points on a graph charting historicity vs. accessibility, all with strong merits and flaws.

How do we Get To Know Characters?

One feeling I had all the way through watching The White Queen was that the motives for all the characters’ decisions felt much more modern. The situation and challenges were still period, but the interior thoughts and motives, Warwick’s ambition—his thoughts and schemes—could have been in House of Cards, George of Clarence’s selfishness in any family drama, and Edward and Elizabeth’s romance in any of a thousand modern love stories. They faced un-modern situations but reacted with modern thoughts, in contrast with Shakespeare-Warwick’s fierce honor or Clarence’s terrified repentance, both of which would feel wildly out of place if you ported them to the modern day.

This is partly a question of historicity, whether the writers aim to present comfortable modern motives in a period setting, or whether they really go the extra step to present the alien perspectives of another time (think Mad Men for example). But it is also very much a question of the TV adaptation, and the issue of “relatability” which always concerns TV executives: how to get the audience to feel comfortable with, relate to, and empathize with the characters. And here is where I am discussing features unique to the TV series, how two staged dramatizations of the same events go about presenting characters so differently.

The White Queen series is roughly 10 hours long; an unabridged Henry VI Part 3 + Richard III runs about 6 hours. Yet I would bet very good money that, if you wrote out just the dialog of both, the script for Shakespeare’s two plays are, together, much, much longer than the script for the entire TV series. In fact, I wouldn’t be surprised if just Richard III turned out to have more dialog than all 10 episodes of The White Queen put together.

Shakespeare has us meet his characters through words: speeches, soliloquies, asides, scenes in which they unpack their grievances and hopes, or even address the audience directly, taking us into their confidence. Warwick, Clarence, York, Richard, Queen Margaret, they all unpack their thoughts and motives to us at length, giving us extremely detailed and specific senses of their unique characters.

In contrast, contemporary television, and The White Queen in particular, tends to show us characters and drama through facial expressions instead. We see short scenes, often with only a couple spoken lines, where much of the content is characters gazing at one another, a tender smile, a wistful look, a flinch as some significant character takes her hand instead of my hand. This is partly because TV wants to have time to show off its sets and costumes, extras and action sequences, and its fashion-catalog-pretty actors and actresses, but it is also a strategic writing choice. There are rare exceptions—notably the British House of Cards—but for the rest of TV the writers are thinking of the visuals, of faces, angles, shots, often more than text. Here Warwick’s daughter Anne Neville is a fantastic example.

Anne is one of the central characters of The White Queen, whom we watch through all the tumults caused by her father’s ambition, and well beyond, receiving hours of screen time. Yet more often than not, we learn what is happening with Anne through a few quiet words—often timidly voiced and cut off by the authoritative presences of men or more powerful women—and through her facial expressions. There are entire scenes in which Anne never says a word, just watching events and communicating her pain or fear to us in silence. This kind of characterization is effective, and particularly effective at making Anne easy to relate to, because it is strategically vague. We know from her face when she is hurt, when she is happy, when she is longing, when she is terrified, but because there are few words to give the feelings concrete shape, the viewer is left to imagine and fill in the details of what she is really feeling. We can fill in our pain, our longing, our hope or happiness. This makes Anne (and others) effortless to relate to, because half the character is conveyed by the script and actress, but half comes from our own feelings and imagination.

The books, of course, are nothing like this, setting out the characters entirely in text, but as we compare drama to drama the difference is stark. Anne Neville is a far more minor character in Richard III, appearing in only a few scenes. And yet, with so many more words to give clear shape to her grief, her wrath, I feel as if I know Shakespeare’s Anne better and could describe her personality more vividly after just one brief scene than I know after watching several hours of The White Queen. Shakespeare’s Anne is a fierce, witty spitfire, matching eloquent Richard tit for tat, but it isn’t just that. The TV version is meant to be a mirror, a half-blank space for the viewer to reflect and imagine how we would feel in such a situation, whereas Shakespeare’s is something entirely new, external, alien, a powerful and unfamiliar person from an unfamiliar place and time, who makes us sit up and go “Wow!”—having feelings about the character—instead of sitting back and sharing feelings with the character. Both storytelling approaches are powerful, but radically different.

It is somewhat ironic for a retelling which is so focused on overturning historical silences—giving voices to the women, to omitted characters like Richmond’s mother, and to the characters Shakespeare vilifies—to then impose new silences by choosing to have so many scenes be nearly wordless. Again, this is only a feature of the television series, but, since it is the women more than the men who communicate their pain and passion with wistful gazes, it is an interesting window on how often we portray women—especially in a historical context—with silence, and with ways of communicating despite silence.

Though women are far from the only ones affected by this technique. Richard III is perhaps the most radically transformed character, and not only because he has been de-propagandized. Shakespeare’s Richard makes the audience into his intimate co-conspirator, opening up his innermost schemes and taking us into his special confidence. Great Richards like Ron Cook in the Jane Howell BBC Shakespeare version can make us fall in love with him in a single three-minute speech, a fascinating experience so deep into the Henriad, where we have been loving, hating, and sympathizing with many different characters in balance, until a charismatic Richard shows up and announces that, for the remaining 4 hours, we will love only him. Not all Richard III productions make Richard so charming, but all versions do make him have a special relationship with the audience, as the text requires. By contrast, The White Queen, relying on silences and gazes, transforms Richard into a closed and quiet figure, often inscrutable behind his mask of movie-star beauty, whose thoughts and motives we (empathizing with Anne) struggle desperately to understand. This reflects the reality of Richard’s associates, never knowing whether we can trust him or not, introducing a kind of loneliness, and an opportunity for the viewer to imagine a personality, and be in suspense as to whether our guesses will prove right. In both cases the viewer sympathizes with Richard, but the way we sympathize, and the degree to which we feel we know and trust him, is completely reversed. (For more see Jo Walton on Richard III and complicity.)

Of course, the ratio of words to gazes in Shakespeare also varies production-by-production, as directors decide what to cut, and how much to add. The first season of The Hollow Crown demonstrated a lot of television theatricality, adding in not only long battle scenes but vistas of town and country, street scenes, travel scenes with panting horses, and periods of Henry IV or Prince Hal just gazing at things. Any production of a Shakespeare play has visuals, faces, line-of-sight, but the television tendency to place the heart of the storytelling in faces and expressions more than in words and voices is certainly a modern trend, visible in how much more silence recent Shakespeare films have than older ones, and in how many fewer words per minute 21st century historical TV dramas tend to have than their mid-20th-century counterparts. The Hollow Crown also tends to break up the long speeches into chunks, interspersing them with action, cutting away to different scenes, or omitting large chunks, so we hear short snatches of five or ten lines at a time but rarely ever a long monologue. This brings Shakespeare’s language more in line with current TV writing styles—short scenes and quick, dramatic encounters with lots of close-ups and dramatic looks—more comfortable, perhaps, to many viewers, but dramatically changing the pacing of how we get to know characters, and the degree of intimacy the audience feels with major characters like Falstaff or Prince Hal, who we normally get to know largely through their direct addresses to the audience. It will be fascinating to see how they handle Richard III, who has so many of Shakespeare’s most powerful audiences addresses.

Many Ways to Experience the Wars of the Roses

Bigger budgets are giving productions like The White Queen, The Hollow Crown, and Game of Thrones horses and battle scenes undreamed-of by the earlier filmed versions of the Wars of the Roses, like the sets the BBC produced in 1960 and 1983 (see my earlier comparison). As we look forward to the second season of The Hollow Crown this year, we can also look forward for the first time since 1960 to an easily accessible complete version of the Henriad with one continuous cast. In fact, hopefully more complete since the 1963 Age of Kings, while excellent, cuts a lot of material, especially from the Henry VI sequence, in a way which leaves it hard to understand the events. So I’m excited. But, thinking of our graph of historicity vs. accessibility, and thinking of the first half of The Hollow Crown and the choices it made in minimizing Shakespeare’s period humor and upping the starkness with black costumes and grimdark aesthetics, I expect it to be a bit farther down our graph away from the raw, powerful (if sometimes Wikipedia-requiring) historicity of a straight-up theatrical production.

What do I recommend, then, if you want to experience the Wars of the Roses? Since intertextuality and comparing multiple versions are my favorite things, I recommend all of them! But if you want to prep for the second season of The Hollow Crown by treating yourself to a straight-up version of the Henriad, I recommend the versions which are most theatrical, filmed plays rather than elaborate productions with horses and castles, because they make the text and Shakespeare’s theatricality shine best, and will excel in all the areas The Hollow Crown is weakest at, and vice versa, giving you a perfect perspective of the range of ways these histories can be produced.

You can get the whole 1960 eight play sequence in one box with Age of Kings (which is currently the only easy way to get it all), but unfortunately it cuts the plays a lot, slicing the 9.5 hours of Henry VI down to just 4 hours, and leaving something which is very difficult to follow. You can assemble a more complete and powerful version if you pick and choose. For Richard II I recommend the Derek Jacobi version in the BBC Shakespeare Collection, though the Hollow Crown version and the Royal Shakespeare Company version with David Tennant are also delightful choices. As for Henry IV and Henry V, the RSC versions are very good (with a particularly brilliant Hotspur), but I recommend the Globe productions directed by Dominic Dromgoole, with Roger Allam and Jamie Parker, filmed on the reconstructed Globe. The three DVDs cover Henry IV Part 1 and Part 2 and Henry V, with magnificent period stagecraft, funny scenes that actually are funny, and the best rapport between Hal and Falstaff that I have ever seen.

Getting the second half is harder, since it’s so rarely performed. If you want the omnipotent version (the one whose Margaret gives me nausea-to-tears whiplash in 8 minutes), you want Jane Howell’s matchless 1983 version, made for the BBC Complete Shakespeare Collection. Staging all three Henry VI sections and Richard III with one (brilliant!) cast on one set, Howell communicates the tragically escalating destruction of the wars by letting successive battles and murders gradually transform her stage from colorful play castles to charred and blood-smeared ruins, and introduces even richer intertextuality into the plays by reusing actors in roles that relate to each other and comment on the gradual decay of war-scarred England. Unfortunately, the Jane Howell productions are only available in the complete 37 production DVD Region 2-only box set of the BBC Shakespeare Collection, which costs ~$140 + (for Americans) the cost of buying a region free DVD player (usually about $40 online). But, for lovers of historical drama, the expense is 100% worth it for the Henry VI sequence alone, 200% worth-it since you also get amazing productions of Hamlet, Richard II, The Comedy of Errors, brilliant actors including Helen Mirren and Jonathan Pryce, and the rare chance to see never-produced plays like King John, Troilus and Cressida and Timon of Athens. A few productions in the BBC Shakespeare set are more miss than hit—especially the comedies—but the net is worth-it.

Those are my best recommendations, refined over a skillion viewings. But, of course, the best way to approach the Wars of the Roses is to remember that all these authors—Shakespeare especially—expect the viewer to know the events already. Foreshadowing, inevitability, the curses and precedents which prefigure what must come, Shakespeare uses these (the White Queen too) to create a more complicated relationship between the viewer and events than passively discovering what happens—we’re also supposed to be judging what happens, thinking about what is inevitable, what early sins lock us into later tragedies, and reflect on how the characters in the time feel the Hand of Providence at work in these events (something Philippa Gregory plays with delightfully in her development of Henry Tudor’s mother Margaret). So, in the opposite of standard fiction-consuming advice, go spoil yourself! Read up on these events and people! Watch it, and then watch it again! The more you know about events at the beginning of a viewing the more you will get out of what Shakespeare, Jane Howell, Dominic Dromgoole, and Philippa Gregory are doing, and why historical drama has a special power that pure invention doesn’t.

Because there are real bones under Greyfriars.

The author of historical fiction is like a dancer moving through an obstacle course, making art of how to move between the parts that are fixed and immutable. The better you know that course, the more you can admire the fluency and genius with which a particular dancer navigates it, and how different dancers make different art from moving through the same challenges. There is no best version; the best version is having more than one.

Ada Palmer‘s first novel “Too Like the Lightning” (book 1 of Terra Ignota) is coming out from Tor May 10th, 2016. She is a historian, working primarily on the Renaissance, Italy, and the history of philosophy, science, books and printing, heresy, and freethought, as well as manga, anime and Japanese pop culture. She writes the blog ExUrbe.com, and composes SF & Mythology-themed music for the a cappella group Sassafrass.