Peter B. Gillis planned on a dual career, one as a Medieval scholar, the other a writer of comics. In the late 1970s, he collaborated with a very young Frank Miller for one of his first Marvel stories, which centers around a poker game organized by The Thing. Another story describes a day in the life of the Red Skull. Soon afterwards, he began his graduate studies at the University of Chicago, where he had received his BA a few years before. He never finished his dissertation and ended up pursuing the life of a freelancer instead.

Someone once told me that they don’t give out prizes for reading. In Gillis’ case, that’s unfortunate, as he was both a fine writer of superheroes, as well as a brilliant, eclectic student of books. He owned a 19th-century edition of Margaret de Navarre’s 16th-century Heptaméron, complete with engravings of naked women, thus marking it as a work of pornography. During our conversation on May 7, he fell into a long monologue about the history of the Ottoman Empire, and mentioned, as an aside, that he was reading August Niemann’s The Coming Conquest of England, a dystopian novel from 1904 that predicted a war with Germany. When I first heard the news of his death last week at the age of 71, I imagined a recently vacated curiosity shop. Something rare had been lost.

It’s not my place to write Gillis’ obituary. I first heard his name two months ago, and only talked to him that once. I now know at least something about Strikeforce: Morituri, a series he co-created in the late 1980s, which has enjoyed a cult following, and his work on Dr. Strange, his favorite Marvel character. The occasion for our conversation, however, was a footnote in his career, a speech given by Captain America, probably the best one the superhero has given in all his 84 years. Democracy needs people like Gillis. It needs oddball books, oddball readers, and oddball writers. And it needs the man who wrote one of the best paragraphs to appear in a superhero comic during the final decade of the Cold War.

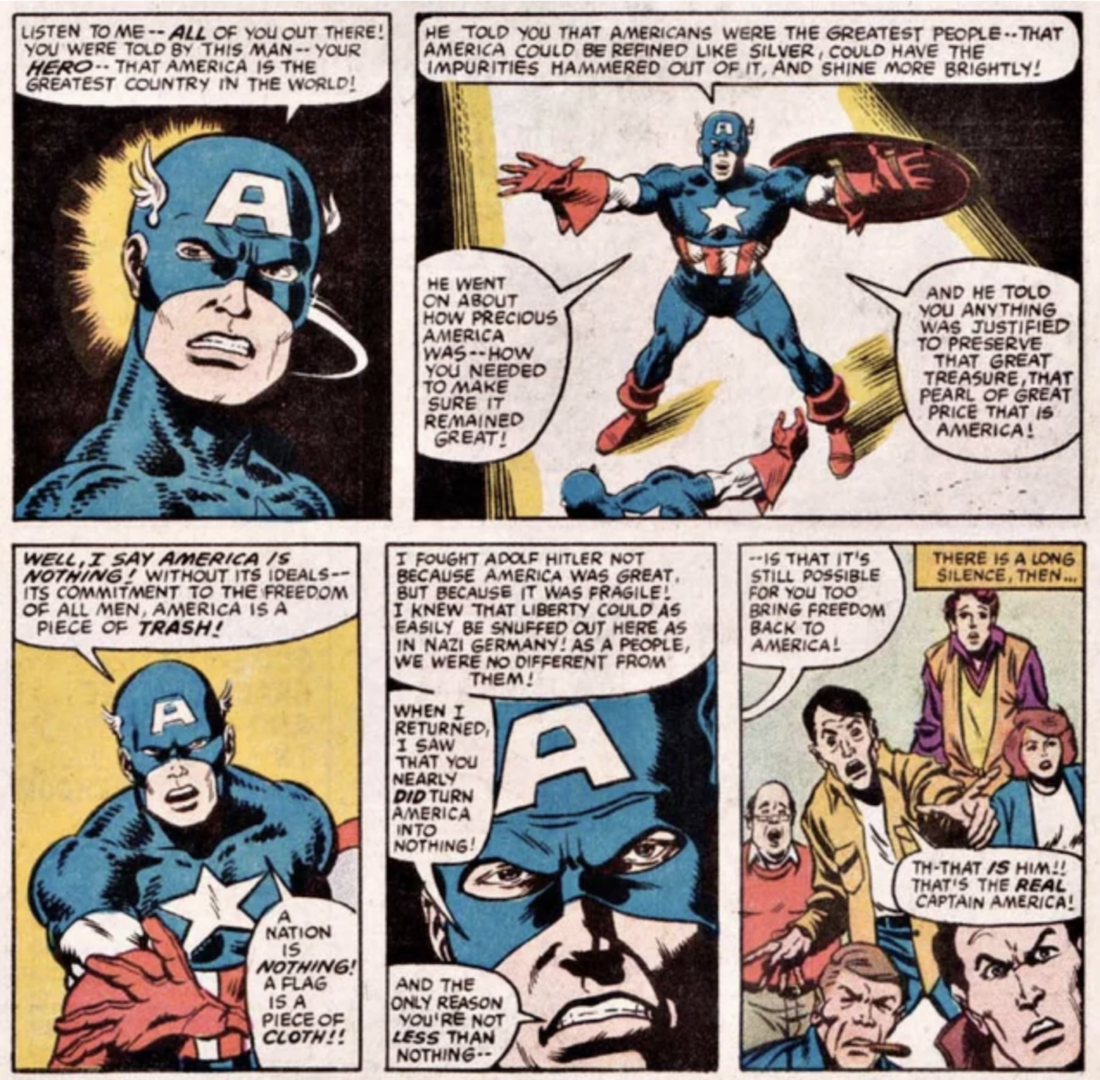

Listen to me — all of you out there! You were told by this man — your hero — that America is the greatest country in the world! He told you that Americans were the greatest people — that America could be refined like silver, could have the impurities hammered out of it, and shine more brightly! He went on about how precious America was — how you needed to make sure it remained great! And he told you anything was justified to preserve that great treasure, that pearl of great price that is America! Well, I say America is nothing! Without its ideals — its commitment to the freedom of all men, America is a piece of trash! A nation is nothing! A flag is a piece of cloth! I fought Adolf Hitler not because America was great, but because it was fragile! I knew that liberty could as easily be snuffed out here as in Nazi Germany! As a people, we were no different from them! When I returned, I saw that you nearly did turn America into nothing! And the only reason you’re not less than nothing — is that it’s still possible for you to bring freedom back to America!

There are two short phrases here, nine words out of 204—“America is nothing!”; “America is a piece of trash!”—that shock even within context. In the past decade, no politician—Squad member or centrist—has given a speech with such damning soundbites. It takes Captain America, greatest of all soldiers, man of violence, blonde-haired and blue-eyed beneath the mask, to describe so plainly the threat of American nationalism.

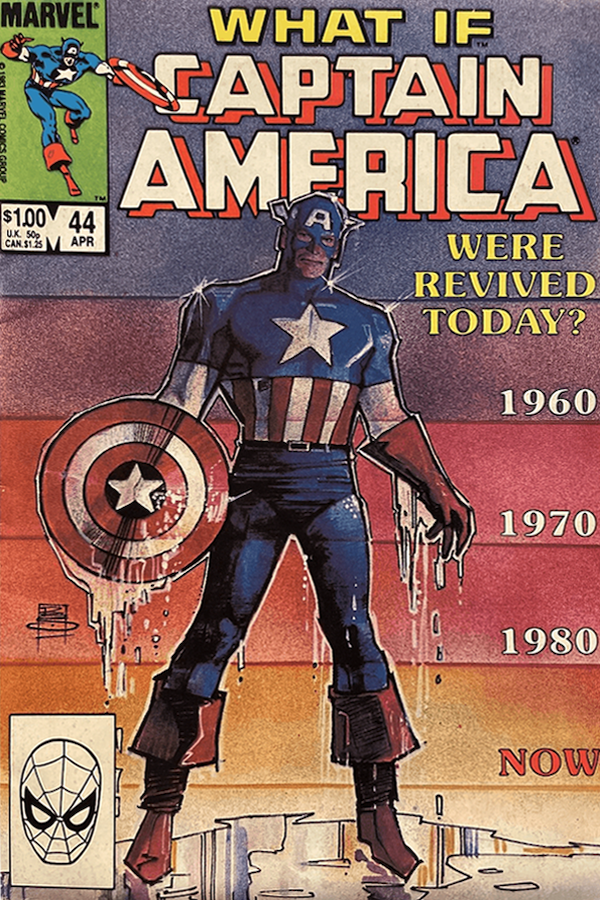

And it’s hard to imagine any mainstream politician speaking those words in November 1983, when they appeared in the 44th issue of What If…?, a Marvel series that imagines alternate histories for its characters1. In Gillis’ “What If Captain America Were Not Revived Until Today?”, drawn by Sal Buscema, the lost World War II superhero does not emerge from his icy prison in the North Sea in the 1960s, as he does in regular continuity, but two decades later. By that point, fascistic supervillains have seized control of the American government.

The speech itself has become a totem—surfacing on social media in 2016 and reappearing perennially since. We want a Captain America, one who will save us not from the Nazis or the terrorists, but from ourselves.

In the ethos of What If…?, it’s the circumstances not the characters who change. The stories can be whimsical, but they often end in tragedy. In one Gillis story, Aunt May dies instead of Uncle Ben and his father figure’s well-meaning overparenting proves unfortunate for Peter Parker’s career as Spider-Man. In another, Sue Richards dies in childbirth having been infected by one of the Fantastic Four’s cosmic foes. A heartbroken Reed Richards avenges her by committing murder-suicide; given the right circumstances, even a considered man of science can go berserk. (Go ahead and have some fun. What if a spider bite cursed Wilbur with an incurable case of arachnophobia? What if Mr. Darcy died in the Napoleonic Wars?)

By the early ’80s, Captain America was more than four decades old, and it requires a little backstory to explain how, in What If…? #44, the physical embodiment of patriotic fervor makes an impassioned argument for liberal humanism.

The hero made his first appearance on the cover of Timely’s Captain America Comics #1, published in December 1940, where he delivers a nasty cut to Hitler’s face. Superman would become the preferred superhero for GIs in the European theater, but that image on the cover, drawn by Jack Kirby a full year before America’s entrance into World War II, is iconic. Kirby and his collaborator Joe Simon left Timely soon afterwards, but the character remained popular until 1945. Interest in wartime superheroes waned at that point, and Captain America quietly faded out in 1950.

Atlas, Timely’s corporate successor, revived the character as a fierce commie-smasher for a few issues in 1953. In the mid-’60s, he would be revived again by Stan Lee, who slyly elided the hero’s sojourn in the early years of the Cold War. Rediscovered by The Avengers, Steve Rogers/Captain America is thawed out of his icy prison, and thanks to the super soldier serum that had originally turned him into a superhero, he remains alive and powerful.

The character was smartly drawn throughout the Silver Age. Kirby, having returned to the company, now renamed Marvel, imbued the hero with a balletic athleticism he lacked 20 years before. Jim Steranko saw him as a lonely figure, a man out of time in a noir-ish cityscape. But Lee, a middle-of-the-roader who avoided anything too controversial, dulled the character. The superhero who wore an American flag had nothing to say about the Vietnam War.

That changed in the early ’70s, with a young writer named Steve Englehart whose first Captain America story explains the character’s brief career during the McCarthy era. As it turns out, in Englehart’s telling, Atlas’ Captain America was a counterfeit version, a college professor who discovered the secrets of the super soldier serum and underwent plastic surgery to become the superhero he idolized throughout his childhood. He then recruits a young man to become his Bucky, Captain America’s sidekick from World War II. Due to a flaw in the serum, the ersatz Captain America and Bucky’s hatred for communism soon morphs into psychotic racism. Government officials, disturbed by their insanity, have the two men cryogenically frozen.

Richard Nixon visited China in February 1972, and Englehart’s story appeared that summer. A janitor, enraged by Nixon’s decision, unfreezes the two one-time commie-smashers, who are in turn defeated by Steve Rogers—the “real” Captain America—and his Black partner Falcon, a.k.a. Sam Wilson, a Harlem social worker. Readers, at least those more skeptical of their government, now knew that the country’s finest patriot was on their side. Yet the battle traumatizes Rogers. What does it say about Captain America, who partners with a Black man, that someone who emulated him could so easily fight for everything he hates?

Englehart would raise the stakes in 1974 with a Watergate-inspired storyline whose run coincided with the final months of Nixon’s presidency. Captain America traces a nefarious organization known as the Secret Empire to the White House. The story ends violently with the suicide of the unnamed president at the center of the conspiracy. Is he Nixon? “I swore up and down that it wasn’t,” Englehart later said. “But once it was in print, I had no problem admitting it.” It’s unclear if Marvel’s executives were also unable to connect Englehart’s Quentin Harderman, an ad-man-cum-propagandist-cum-criminal mastermind, to Nixon’s aide H.R. Haldeman.

Englehart’s Captain America compares the new leaders of his country to the enemies he had fought in World War II. “I have seen America rocked with scandal — seen it manipulated by demagogues with sweet, empty words,” he says. For a brief period, he gives up his Captain America persona and becomes Nomad, though he eventually returns to his original role.

There have been other permutations of the character that suggest a small-c conservative streak, but the idea of an American hero in an existential crisis, unsure of what he is and what he has fought for persists. Future writers introduced more right-wing villains. In recent years, Fox News pundits have condemned pro-immigrant and anti-racist storylines, including one written by Ta-Nehisi Coates. The MCU has lightly touched on this feature of the character, but Chris Evans’ unoffending Eagle Scout lacks the edge necessary to communicate his tortured ambiguity.

Gillis, like Captain America, underwent his own rapid political evolution. He came to the University of Chicago in the late ’60s tilted away from the leftist mood of the era, but his undergraduate years proved formative. The killing of Fred Hampton, not too far from campus, affected him, as did Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee, Dee Brown’s history of Native genocide.

By the time he graduated, Marvel Comics was moving in a riskier direction with a group of new creators—among them Englehart—and Gillis considered them heroes. He described Don McGregor, who was then writing Black Panther stories in the Jungle Action series, as “far more ferocious and far more courageous” than himself. When, some years later, he would begin his career as a comics writer, he too would try to push boundaries. “I knew I was not in the charmed position of writing the major books,” he told me. “There is an advantage to that in that they weren’t paying as much attention to me.”

There were limits. At the time he wrote What If…? #44, he co-created a Black Panther story in which T’Challa does battle in South Africa, a storyline that unnerved Marvel’s higher-ups. In order to please one editor, Gillis changed the country’s name to Azania, which may sound like one of many imaginary countries in the Marvel universe—Latveria, Genosha, Wakanda—but is in fact a direct reference to the Azanian People’s Liberation Army, an anti-apartheid military group. It wasn’t enough. The series was shelved with no explanation for five years, at which point an editor took it out of the drawer. The anti-apartheid position was no longer controversial. “That was 1988 when it came out, around the time most people were thinking, ‘Oh racism is actually bad,’” Gillis said.

Gillis did not have to invent any characters for What If…? #44, and Buscema, who had been drawing Captain America for more than a decade, did not have to change his style. In the story, the counterfeit Captain America—whose real name is William Burnside—emerges with the counterfeit Bucky in 1972, as he does in regular continuity. He quickly gains popularity and appears on a talk show where he notes his discomfort with anti-war and civil rights demonstrators. Gillis’ take on Burnside is slightly different than Englehart’s, less a pathological bigot and more a charmer of the Ronald Reagan variety. He eventually becomes a patsy for supervillains who traffic in xenophobia, racism, and anti-Semitism. They recruit him as a spokesman for the America First party, which has a secret goal of transforming the country’s democracy into an absolute monarchy.

Steve Rogers emerges in a 1983 that might as well be 1984. A gestapo-like police force dons the Captain America insignia. The U.S. Navy, due to the nature of its service, out at sea, away from the masses, becomes a surprising refuge for Black people and Jews. Harlem is a new Warsaw Ghetto.

To repeat, only the circumstances have changed. The characters are eternal. In an Amazing Spider-Man storyline published in the fall of 1968, Peter Parker expresses discomfort with a campus protest modeled on the uprising at Columbia the previous spring. In Gillis’ story, the moral lines are more obvious and Peter gives up his Stan Lee-influenced fence-sitting. He is introduced as a guerilla, with a gun slung over his shoulder. Under the guidance of J. Jonah Jameson, he joins an underground movement alongside Nick Fury and Sam Wilson.

Captain America’s speech appears in the second to last page of the story. The heroes have defeated Burnside and his fellow rogues just when they are presenting themselves on national television on behalf of the aspiring overlords. This Captain America makes perfect sense. Why wouldn’t Steve Rogers, transported in time past the McCarthy era and the Cuban Missile Crisis, be disgusted with government corruption and mendacity? Why wouldn’t this son of the Lower East Side, created by two working-class Jewish boys in the early ’40s, be a New Deal Democrat? Why wouldn’t a soldier, like any number of veterans, be riven with contradiction and doubt? When he gives the speech, I forget that his ventriloquist is a writer forged in the turmoil of the late ’60s.

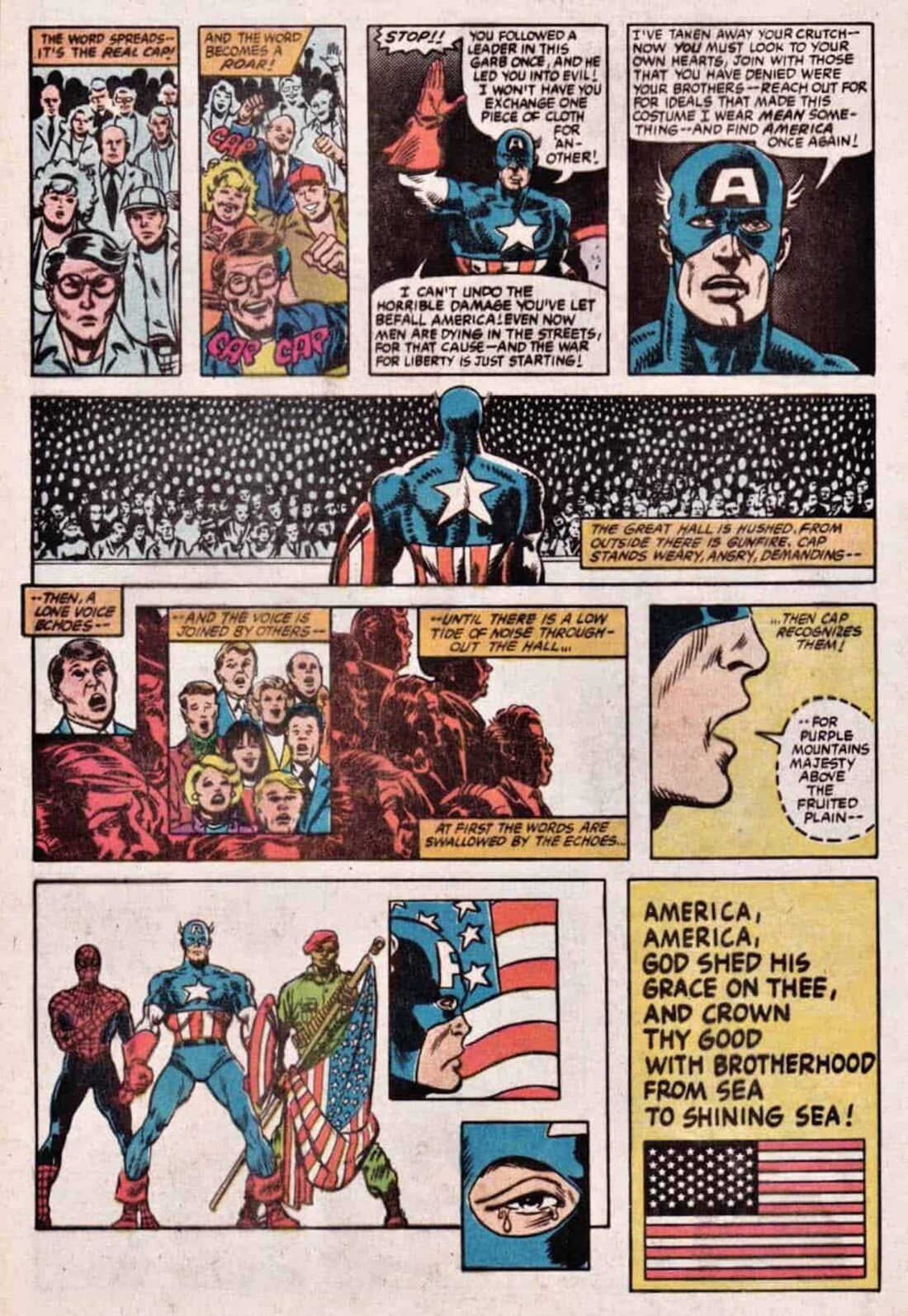

Those who have meme-d it on social media, however, leave out the final page.

The crowd, shocked by the reappearance of the Greatest Generation-era Captain America cheers him. “STOP!!” he says. “You followed a leader in this garb once, and he led you into evil! I won’t have you exchange one piece of cloth for another!” He tells them that he can’t undo the damage they have already done to themselves and their country. “I’ve taken away your crutch — now you must look to your own hearts, join with those that you have denied were your brothers — reach out for ideals that made this costume I wear mean something — and find America once again!” The hall falls silent. One man starts singing “America the Beautiful,” and everyone, including a tearful Captain America, joins them.

Gillis called the scene hokum, but it is more disturbing than moving, and it presents an enigma. “Captain America led them there and Captain America was going to lead them out,” he told me. But if a populace needs an anthropomorphic American flag to tell them not to idolize the American flag, then their new position is truly fragile. The words of “America the Beautiful” given the right tone and inflection, can easily turn into a call for Blut und Boden. After all the people already know the words to the song, and they had probably sung it before while laying the ground for a neo-Holocaust.

But the speech reminds us that there is still a point to superheroes, particularly those from the pre-revisionist era, particularly Captain America, particularly this Captain America. The Amazon series The Boys depicts a Burnside-like parody of Captain America named Soldier Boy, an embodiment of the show’s immature nihilism. Nihilism is too easy, a copout. The hope, however faint, in the final pages in Gillis’ story is difficult, and real.

Bill Sienkiewicz drew the cover for What If…? #44 and his illustration of the hero has little in common with Gillis and Buscema’s version on the inside. “I wanted him to feel more iconic, so I just tried to make him look as heroic and clean-cut and strong looking as possible. I in NO way wanted any of the darker, distressed aspects of my work to creep in,” he wrote me in an email. “I deliberately left any politics or hints of ‘liberty vs. totalitarianism’ out of it.”

When I look at Sienkiewicz’s Captain America, I feel the same way I feel when I see an American flag on a front lawn, unaccompanied by any other symbols. I don’t know the beliefs or values of the person who flies it, whether they embrace it in the spirit of George Custer or Ira Hayes, Charles Lindbergh or Paul Robeson.

But I still believe, or maybe just hope, that we share at least one inch of common ground and that we can see each other as fellow citizens in a body politic, deserving of mutual respect and fundamental human rights. In his moment of rage and desperation, Gillis’ Captain America misspeaks. The American flag always communicates an idea, even if the idea itself is not always clearly defined. It is never just a piece of cloth.

- Despite the publication dates noted in the article, Captain America Comics #1 was cover-dated March 1941 and What If…? #44 was cover-dated January 1984. ↩︎