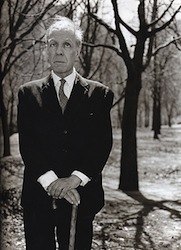

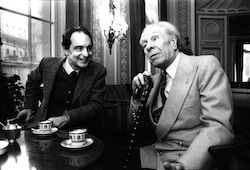

August 25 marks the eleventy-first birthday of Argentine literary giant Jorge Luis Borges. Borges died in 1986. Unable to interview Borges, Jason opted instead to interview Henninger.

Jason: Do you think of Borges as a magic realist or a philosopher?

Henninger: Both. I consider Borges not merely the best of the magical realists but one of the best writers of any genre, and I love his fiction and nonfiction equally. He was a philosopher who drew from literature and philosophical works with equal respect for each.

Jason: I agree, of course. But even as you call him a philosopher, I’m challenged to say what exactly he believed.

Henninger: What fascinated him is far clearer than any conclusions he drew. He’s often associated with labyrinths, and when we think of labyrinths, it’s the twists and turns that matter, not the exit. Better to be lost somewhere fascinating than have a clear path through a dull place.

Jason: But, surely he believed something.

Henninger: Well, he wasn’t nihilistic, if that’s what you mean. But what makes him so wonderful to read is not that he leads you to an inevitable understanding but rather that he creates an array of questions of potential, multiplicity, historic and ahistoric views. Investigations of identity as a dream within a dream perplexed and fascinated him. I think he would have liked the They Might Be Giants line, “Every jumbled pile of person has a thinking part that wonder what the part that isn’t thinking isn’t thinking of.”

Jason: And yet despite the inward focus, he doesn’t come across as terribly egotistical.

Henninger: True, though the same cannot be said of you or me. I’ve always wondered if anyone ever told Borges to go fuck himself. If so, did he?

Jason: You are so crass! Keep making that sort of comment and no one will take either of us seriously.

Henninger: I’m terribly sorry. I’m beside myself.

Jason: Watch it!

Henninger: Okay, I’ll get this back on track. Borges didn’t hold with any particular religion, but expressed interest in several. In his essays, he wrote several times about Buddhism. How well do you, as a Buddhist, think he understood it?

Jason: Remarkably well, considering that translation of Asian languages into English (Borges spoke English fluently) has improved dramatically since his day, and he was primarily an observer of Buddhism rather than a practitioner. I wonder what insights he’d have after reading current translations, but even with inferior translations he grasped the essence of eastern thought with commendable clarity. Not that I agree with every word he wrote on the subject, though.

Henninger: For example?

Jason: In “Personality and the Buddha” he refers to one of the Buddha’s titles, tathagata, or “thus come one,” as “he who has traveled his road, the weary traveler.” This “weariness” isn’t consistent with the Buddhist view that attainment of Buddha-hood is liberating, even exhilarating. It’s not a wearying thing to experience enlightenment, surely. Borges, here, seems to cast the Buddha as some lone, worn philosopher burdened with life’s finality. That image might apply more to Borges than to the Buddha.

Henninger: What did he get right?

Jason: I think he understood—though I’m not completely sure he believed—the Buddhist view that all life is connected and infinitely variable, that phenomena are both distinct and interrelated at once, that an object or event is not self-defining but dependant on a vast causal context. In a sense, many of his stories and essays form a bridge between dualistic and non-dualistic views. In “Borges and I,” for example, the reader wonders which Borges wrote the text. The dualistic answer, that either the narrator or the “other Borges” are real (or that neither are) but not both, isn’t satisfactory. The non-dualistic view is that they are both Borges, or that the person of Borges is both self and other, observer and observed, all equally real.

Jason: I think he understood—though I’m not completely sure he believed—the Buddhist view that all life is connected and infinitely variable, that phenomena are both distinct and interrelated at once, that an object or event is not self-defining but dependant on a vast causal context. In a sense, many of his stories and essays form a bridge between dualistic and non-dualistic views. In “Borges and I,” for example, the reader wonders which Borges wrote the text. The dualistic answer, that either the narrator or the “other Borges” are real (or that neither are) but not both, isn’t satisfactory. The non-dualistic view is that they are both Borges, or that the person of Borges is both self and other, observer and observed, all equally real.

Henninger: If I ever get a time machine, I’m inviting Borges, Nagarjuna, and Douglas Adams to dinner. And then my head will explode.

Jason: Don’t forget your towel. Veering away from religion, how does Borges compare to other magical realists?

Henninger: He’s more concise than any other, though that’s hardly an original observation. Garcia-Marquez and Allende feel heavy and fragrant and swampy, compared to Borges. Reading Aimee Bender is like going on a date with a person you suspect is crazy, while Borges seldom even acknowledges sexuality at all. Laura Esquivel feels like a hot kitchen while Borges feels like an old, cool library. Possibly because of his poor eyesight and eventual blindness, visual details aren’t always major factor in his writing. I think that when you consider how much of descriptive writing is visual, it’s impossible not to be concise when you leave a lot of it out. Sometimes, he opted for very nonspecific description, as with the famous phrase, “No one saw him disembark in the unanimous night.”

Jason: He disliked that line, later in life.

Henninger: I think the younger Borges enjoyed the inherent puzzle of describing an unseen event, written so that even the reader doesn’t quite know what he or she is picturing. But the older Borges found it sloppy. I suspect they disagreed often, though the older Borges admitted once to plagiarizing himself.

Jason: How does he compare to Italo Calvino?

Jason: How does he compare to Italo Calvino?

Henninger: Okay, earlier I called Borges the best magical realist, but given his fondness for multiplicity perhaps he’ll forgive me if I say Calvino is also the best. Calvino is a gentler read than Borges, a little more emotional and lighthearted, but no less capable of planting philosophical seeds that grow into thought-forests. Calvino, as a child, cut out frames of wordless Felix the Cat comics and rearranged them to tell multiple stories. To some extent, this remained his storytelling method throughout his career (especially in Castle of Crossed Destinies, a frame narrative built around tarot cards). How cool is that?

Jason: Calvino wrote on several occasions of his fondness for Borges. Did Borges return the compliment?

Henninger: Not that I am aware of. But Calvino’s dying words are said to have been, “I paralleli! I paralleli!” (The parallels! The parallels!). I can only imagine Borges would have loved that.

Jason: Thank you for your time.

Henninger: Time is the substance from which I am made. Time is a river which carries me along, but I am the river; it is a tiger that devours me, but I am the tiger; it is a fire that consumes me, but I am the fire.

Jason: Show off.

The interviewer and interviewee suffer from a sense of unreality, as do many in Santa Monica. They wish thank Aimee Stewart for the illustration leading this article.