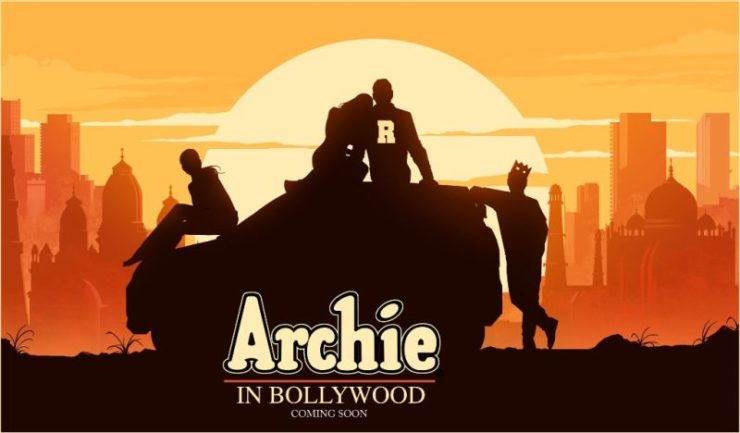

In 2018, it was announced that there would be a Bollywood-style live-action adaption of Archie comics produced in India. The freckled redhead and his friends Betty, Veronica, Jughead and the gang will be reimagined as Indian teenagers.

Initially, this announcement may seem like a natural progression for the Archie brand thanks in part to the overwhelming success of Riverdale both here in the U.S. and internationally. But that show alone isn’t solely responsible for Archie’s popularity in India, nor is it a recent phenomenon. The fact that this is the first American comic book to receive a big screen adaptation for South Asian audiences makes perfect sense: for as long as I can remember, Archie comics have always been part of Indian culture.

If my childhood in India was a pop culture mood board, it would look pretty familiar to most ‘90s kids the world over. I watched He-Man, G.I. Joe, and Jem and the Holograms. My bedroom had movie posters of Jurassic Park and Titanic. Michael Jackson, Backstreet Boys, and The Spice Girls made frequent rotation in my Walkman. My friends and I read and traded Goosebumps, Animorphs, and Sweet Valley High books voraciously.

If you went into any comic section of a book store in India you would find all the usual suspects (Batman, X-Men, Spider-man, etc.), a few international publications (Asterix and TinTin were very popular), and local Indian series offered in English and regional languages (Tinkle, Amar Chitra Katha).

But you would also find a literal wall of Archie comics, with publication dates ranging from the 1950s up through the previous week. They shared shelves with Sabrina the Teenage Witch, Katy Keene, Josie and the Pussycats, Little Archie, and even Wilbur Wilkin, which ceased publication in 1965! (I should really find those and see if they’re worth anything…)

There was also the cavalcade of big-headed, bug-eyed children from Harvey Comics like Wendy the Good Little Witch, Casper the Friendly Ghost, Richie Rich, Little Dot, and Little Lotta. Disney comics that appeared to have been in syndication prior to the Vietnam War also tempted our pocket money. Not all of these were newly released nor published specifically for the Indian market. Some were leftover stock, some were bootlegged reprints, and some were imported illegally from abroad to be sold at a high markup. Regardless, there was always a steady stream and a broad selection anytime you went browsing.

Imagine my surprise when I discovered that these beloved series, seemingly preserved in amber, weren’t being read all over the world. While I was still in middle school, my family and I visited relatives in Connecticut. I was utterly perplexed as to why I shared so many of the same cultural touchstones with my American cousins…except for Archie comics. Where were the Double Digests? The pullout posters and paper dolls? The ads with 1-800 numbers in the back to write in for a collectible button or bendy figure? The only time I saw a glimpse of Archie was in the checkout counter of a grocery store. My younger cousins had never even heard of the comics. I was so confused.

These comics that seemed so quintessentially Western, so indicative of Americana, had long been abandoned by the children of their original audiences. By the ‘90s, the wholesome hijinks of small-town USA were apparently too precious for modern readers of our age group abroad. Yet they fascinated us in India.

I was intrigued by novel concepts like sock hops, jalopies, and soda shops while being blissfully unaware these were all things of the past in American culture. Even the newer comic books with more modern updates—particularly in terms of pencil work, clothing styles, and newer technology used—recycled plotlines from the ones from decades earlier, like serving comfort food on a newer plate.

In a way, of course, these idealistic and simplistic comics gave us a false perception of American teenage life, but we loved them anyway. Similar preoccupations were mirrored in Bollywood films, as well: love triangles, defying your parents to follow your dreams, and crazy adventures were themes common to both.

Archie comics also gave us glimpses at a kind of unfamiliar freedom, things we could never do ourselves: Dating was out of the question in most Indian households unless marriage was on the horizon. Talking back to our parents (though fantasized about quite often) was unheard of. Chaperoned trips to the movies or the local pizzeria were about as crazy as our outings got.

I am, of course, recalling a fairly privileged existence I led in a country where a handful of those comics could have fed the family begging outside the store for weeks. I went to private school while wondering what it would be like to attend Riverdale High. Studies, tutors, and sports practice left little time to form a pop group like The Archies or the Pussycats. We all sided with sweet, wholesome Betty Cooper since our own lives of nice houses, servants, drivers, and vacations abroad hit a little too close to that of spoiled brat Veronica Lodge.

I get it now. Comics have always been an escape, through which you could become a superhero fighting powerful villains or a brilliant detective solving crimes. Archie was no exception—the day-to-day antics of the residents of Riverdale were just as fantastic and fascinating to young Indian readers as the prospect of leaping tall buildings in a single bound.

Their multi-colored yet fairly whitewashed world rarely touched on serious topics, save for an occasional lesson-of-the-day about seat belt safety or dropping out of school. Degrassi this was not. Meanwhile, in the actual America of the time, the country grappled with gang violence, opioid abuse, and the aftermath of Columbine—many things, for the most part, that Indian children didn’t have to deal with. We had our own issues, however: political riots, a growing nationalist movement, and an increasingly high rate of student suicide owing to extreme academic pressure.

Perhaps it was because Archie offered a vision of a world where these things never happened that we read them with glee. I recall that many parents preferred for us to collect these comics, as they themselves once did, rather than the violent offerings from Marvel or DC. My bookshelves ached under the weight of my collection of, at one point, well over a hundred comic books organized meticulously by character and series. Archie was a common guest at the dinner table and on long drives or flights. When my friends and I hung out, after video games and snacks, we would sit together and read each other’s Archies, sharing funny scenes and punchlines, bragging about our own growing collections at home.

That’s not to say the series hasn’t come a long way over the years. In the past decade alone we’ve seen greater diversity—including the series’ first gay character, vampire/zombie storylines, and even the death of a beloved teacher—thanks to a more realistic rebranding. In 2007 Raj Patel (not the most original name but I’ll let that slide) was introduced as the first Indian character. He goes against his father’s wishes to become a filmmaker and even strikes up a romance with Betty. That would have been so cool to read as a kid; we craved acknowledgement from the West. But better late than never.

By the time my family emigrated to America, I was the age Archie Andrews would have been in high school. Of course, by then, I had long abandoned the notion that the West was anything like the world depicted in those comic books, which I had also stopped reading years earlier.

In January of this year, however, I was back in India on vacation with some American friends. We visited a local bookstore in Mumbai and I saw them looking with amusement and puzzlement at the extensive selection of Archie comics on display. While not as robust as the huge wall-of-comics of my youth, it was a decent selection nonetheless, and certainly far more than what you would find at any Barnes & Noble. For the first time in a long while, I picked one up and flipped through the pages, looking at the familiar characters and scenarios. I smiled.

How funny to hold in my hands something so inextricable from my childhood and yet so foreign to both cultures I belong to: designed to be so typically American; ultimately representing an experience so fundamentally Indian.

Originally published May 2018.

Reneysh Vittal is a writer and cultural critic. He has contributed to VICE, Narratively, The Rumpus, Oxford University Press, and WNYC amongst others. Read more work at his website and follow him on Twitter @ReneyshV