In this bi-weekly series reviewing classic science fiction and fantasy books, Alan Brown looks at the front lines and frontiers of the field; books about soldiers and spacers, scientists and engineers, explorers and adventurers. Stories full of what Shakespeare used to refer to as “alarums and excursions”: battles, chases, clashes, and the stuff of excitement.

For good reason, Robert A. Heinlein is often called the Dean of Science Fiction Writers, having written so many excellent books on such a wide variety of topics… which can make it hard to pick a favorite. If you like military adventure, you have Starship Troopers. If you want a story centered around quasi-religious mysteries, you have Stranger in a Strange Land. Fans of agriculture (or Boy Scouts) have Farmer in the Sky. Fans of the theater have Double Star. Fans of dragons and swordplay have Glory Road. Fans of recursive and self-referential fiction have The Number of the Beast… and so it goes. My own favorite Heinlein novel, after much reflection, turns out to be The Moon is a Harsh Mistress, probably because of my interest in political science—and because it is simply such a well-constructed tale.

Preparing this column gives me a chance to look at works from two different perspectives. First, looking back from the point of view of a young reader, new to the world, and new to science fiction. And the second involves rereading these stories from the viewpoint of an older, more experienced reader, who has seen a lot, both of fiction and of life.

As a youngster, what drew me to The Moon is a Harsh Mistress was the strangeness and adventure of it all. While I recognized the obvious parallels to the American Revolution, it was also chock-full of new ideas. There were political philosophies, like libertarianism, that I had not been exposed to, references to history I was unaware of, and all manner of new ideas and technology, all combined in new and different ways. The characters were exotic and unusual, and the plot galloped right along. It was not as accessible as the Heinlein juveniles that I was also reading at the time, but it was perfect for a young teenager who wanted to read more ‘grown-up’ stories.

Approaching the book again, with most of a lifetime between these two reading experiences, I was even more appreciative of Heinlein’s accomplishment. While there are naturally some predictions about technology that haven’t come to pass in the intervening years, the setting feels real and lived-in. The characters are still compelling. But the element that really shines is the politics. During my life I’ve gained a lot of knowledge on that topic, and I sometimes find that knowledge works against my suspension of belief when reading fiction. But when Heinlein describes the workings of the lunar government, the intrigue amongst the Federated Nations, and when he details the various military actions that take place in the book, I find myself appreciating his broad knowledge and his talent. This book effortlessly convinces the reader that things could happen that way, with each event flowing logically and realistically into the next one. Books containing this much adventure sometimes feel awkward when they move from the tactical to the strategic level—that’s never the case with The Moon is a Harsh Mistress.

About the Author

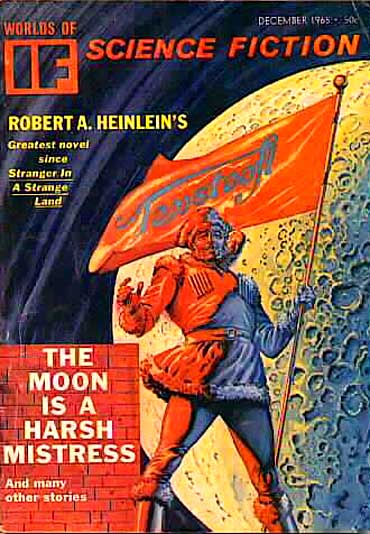

I have reviewed works by Robert A. Heinlein (1907-1988) before, and you can find biographical information in my columns on Starship Troopers and Have Spacesuit Will Travel. The Moon is a Harsh Mistress was serialized in If magazine from December 1965 to April 1966, and then released as a novel. This work dates from the period at which Heinlein was at the height of his popularity—and, some would argue, at the height of his abilities. It was nominated for a Nebula Award in 1966, and won the Hugo Award in 1967. Freed from the heavy hands of his juvenile series editors and from the meddling of Analog’s John Campbell, The Moon is a Harsh Mistress represents an unfettered author, able to express himself however he wished. Heinlein was recognized as one of the leading voices in science fiction by this point in time, and because of the popularity of 1961’s Stranger in a Strange Land, was known even outside of the insular world of science fiction fandom. The Moon is a Harsh Mistress was widely anticipated, and widely respected, and even after over five decades, remains in print and popular to this day.

If Magazine

During the 1940s, Astounding Science Fiction was the most influential magazine in the field. But in the post-war era, Astounding’s dominance began to wane, and new magazines such as Galaxy Science Fiction and The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction began to compete for readers, and started to attract the best writing talent.

If magazine was another of these competitors, founded in 1952. After surviving some early challenges, If was sold to Galaxy Publishing in 1959. In 1961, Frederik Pohl, editor of Galaxy Science Fiction, became the editor of If as well, and continued in that role until 1969, when the magazine was bought by new owners. Under Pohl’s leadership, If found its greatest success, winning three Hugo Awards for Best Magazine. Galaxy featured more established writers, while If published newer authors and more experimental works. After Pohl’s departure, the magazine began to decline and eventually merged with Galaxy in 1975. During its heyday, If published some major works, including James Blish’s “A Case of Conscience,” Harlan Ellison’s “I Have No Mouth and I Must Scream,” Arthur C. Clarke’s “The Songs of Distant Earth,” Larry Niven’s first story, “The Coldest Place” and his acclaimed short story “Neutron Star,” as well as popular series that included Keith Laumer’s Retief stories and Fred Saberhagen’s Berserker stories. In addition, If also first published serial versions of Robert A. Heinlein’s novels Podkayne of Mars and The Moon is a Harsh Mistress.

The Moon is a Harsh Mistress

There are a number of reasons why this novel is so compelling. The first is its realistic setting and politics. The story takes place on the moon in the late 21st Century, when Earth has established a penal colony that produces wheat for a growing and increasingly hungry population. The convicts—political dissidents and displaced people cast off by Earth—have been dumped on the moon, left to their own devices, and are ignored by the authorities as long as they produce the required foodstuffs, which are grown in tunnels under the surface using ice mined from those same tunnels. The Lunar Authority sells basic utilities and supplies to the colony, paying for the food they produce, and ships the food back to Earth via a magnetic catapult. They control prices, and are constantly squeezing everything they can out of the colonists.

Echoing some of the practices Britain used in Botany Bay and other Australian penal colonies, this rationale for a lunar colony feels as real as any other rationale I have ever seen for a lunar colony (although, if I am not mistaken, it would require more water to be found on the moon than we currently think is available). It also gives Heinlein an opportunity to create a libertarian society that he can hold up to our own world like a mirror. While I have my doubts about the viability of such a laissez-faire society in the real world, Heinlein goes a long way toward making the idea appealing, at least in theory. The term “There Ain’t No Such Thing As A Free Lunch!” existed before he wrote the book, but I believe that he coined the acronym “TANSTAAFL,” which became a favorite term in the libertarian community.

His view of the political situation on the Earth is far darker by comparison, displaying his deep pessimism toward human nature and governmental systems. He depicts larger and larger states becoming more and more repressive and totalitarian in nature, and his Federated Nations manifest all the flaws seen in modern extra-national organizations, and then some. Heinlein takes the Malthusian view, running through many of his works (including many of his juveniles), that populations will always increase to outstrip food supplies and governments will always become more oppressive, until those trends are stopped by war, catastrophe, or the opening of new frontiers. I don’t agree with his optimism about libertarianism, or his pessimism toward the human condition, but I have to admit that his conclusions are rooted in broad knowledge and some well-reasoned speculation.

The second reason for this novel’s strength is its core cast of characters, who the plot brings together very quickly. This quartet, among the most appealing of Heinlein’s fictional creations, are the engine that drives the story, and are a major reason that this book ranks among his best. We meet our first two main characters when Manuel O’Kelly Davis (called Manny), a freelance computer technician, is called to repair the master computer of the Authority, the organization that runs the Earth’s lunar penal colony. Unknown to the Authority, the computer, which Manny nicknames Mike (after Mycroft Holmes from the Sherlock Holmes stories), has become self-aware. Mike is experimenting with humor, and Manny offers to review jokes for him to help educate him on what is funny. Mike asks Manny to record a political rally he can’t monitor and is curious about.

Stopping by the rally on his way home, Manny meets Wyoming Knott, a radical from the Hong Kong lunar colony. She is one of the invited speakers, along with Manny’s old professor, Bernardo de la Paz. The Professor points out that if the moon keeps using its limited water resources to ship wheat to Earth, there will be famine and collapse within a decade. Authority guards attack the assembly, and Manny and Wyoh hide in a local hotel, where they are joined by the Professor. The two of them enlist Manny into their conspiracy to overthrow the Authority and stave off this impending collapse. When they explain revolutionary tactics to Manny, he realizes that Mike would be a vital asset to any conspiracy. So they contact Mike, and he agrees to help their efforts.

Manny is the straight man of the bunch, one of many Heinlein characters who fit into the stock role of the “competent man”–a type that will be familiar to anyone who has read much of Heinlein’s work or that of his contemporaries from the glory days of Astounding Science Fiction. At the same time, it’s Manny’s first-person perspective that really makes the book shine. Heinlein does a great job of getting into Manny’s head, understanding what he would know and not know and articulating his opinions on the world. In particular, the patois Manny uses, with its Russian-influenced lack of articles, and words from a broad range of languages, helps the reader feel more fully immersed in his culture. After reading for while, is hard for self not to think Loonie talk like Manny…

The Prof represents another character type who frequently appears in Heinlein’s work: the older, wiser man who often speaks as the author’s surrogate. What sets the Prof apart, however, is his wit and charm. He has a wry sense of humor that comes through loud and clear, and makes him much more appealing than some of the other old-and-wise characters in Heinlein’s work. And while he has very strong opinions and ideals, he is simultaneously very pragmatic about how the real world works.

Wyoh, like many of Heinlein’s female characters, is constructed to be pleasing to what is called the “male gaze.” She also fills much more than that narrow function in the book, however—Wyoh is a dedicated and pragmatic politician. Her personal backstory is touched with tragedy, which gives the character more depth. Her relationship with Manny shows the reader the nature of marriage and romance on the lunar colony, but she also exercises agency and plays a real role in the political decisions throughout the story.

Mike is the character who learns the most in the story, representing a type most common in Heinlein’s juveniles, but not always confined to those books. Mike’s efforts to become more human are charming. While he is anthropomorphized in a way that is probably not realistic (if and when self-aware artificial intelligence arises, I doubt it will present itself in a way that would be recognizably human), this portrayal gives him a lot of appeal. In fact, as a naïve but unusually powerful character, he is like another Mike in Heinlein’s work: Valentine Michael Smith in Stranger in a Strange Land.

A third reason for the strength of The Moon is a Harsh Mistress is the science. Heinlein fills the story with a lot of interesting technological and scientific extrapolation. Of course, like most writers of the time, he got a few things wrong, including a rather timid extrapolation of computer and communications technology (everyone reads paper printouts, the telephones are centrally switched landlines, computers are big and centralized, sounds are recorded in analog formats, and people still use typewriters). But he does give us an interesting view of artificial intelligence, and certainly does portray the mayhem that a machine could cause if its aims diverged from those of its owners/creators. Heinlein also projects prosthetics so useful and advanced that Manny considers his artificial arms superior to the natural arm he lost.

Buy the Book

A Memory Called Empire

Moreover, Heinlein has clearly thought out the implications and technical challenges of using magnetic catapults both on the moon and back on Earth, and the orbital mechanics of both the catapult loads and the ships in the story are impressively realistic. The underground warrens that the lunar colonists live in feel plausible, although in reality, there doesn’t appear to be much available on the moon that makes it worth descending into its gravity well. The use of nuclear-weapon-tipped interceptors has been abandoned as a cure that is worse than the disease, and there are a whole host of things Heinlein does here with manned ships that would probably have been done with autonomous drones, but his military extrapolation is solid, with the military interventions on the moon feeling like realistic responses, and playing out in a way consistent with real-world operations—the impact of the moon’s weaker gravity on attacking personnel is an especially intriguing insight. I can see military commanders making some of the same decisions he describes, and using the same tactics.

And finally, the book is extremely well-plotted. The characters are introduced quickly, and feel like real people from the start, despite the strangeness of their society and environment. The action, kicked off by the attack on the political rally, continues at a rapid pace throughout. Some events are caused directly by the characters, while others happen by chance, and still others are driven by unseen antagonists, which is the way real life works. As in any book about revolution, there is a lot of political discussion, but it never feels like it gets in the way of the action. By the end, you care deeply for the characters and are invested in their situation, and the novel ends on a very poignant emotional note. This is a book that excites you, makes you think, and makes you feel—on a first read, or again upon rereading.

Final Thoughts

So, there you have it—my case for The Moon is a Harsh Mistress being Heinlein’s greatest work. It has all the hallmarks of his most celebrated novels, and the best of science fiction: solid extrapolation of technological and political trends, a well-reasoned and realistic setting, a plot that keeps you turning the pages, and compelling characters.

Now that I’ve had my say, it’s your turn. What are your thoughts on The Moon is a Harsh Mistress? Is it your personal favorite from Heinlein’s work? And if not, what books do you prefer, and why?

Alan Brown has been a science fiction fan for over five decades, especially fiction that deals with science, military matters, exploration and adventure.