Welcome back to the Lovecraft reread, in which two modern Mythos writers get girl cooties all over old Howard’s original stories.

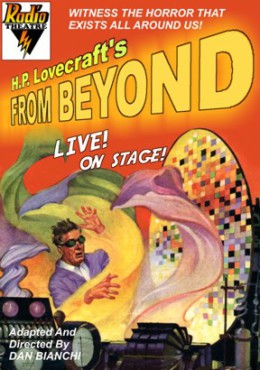

Today we’re looking at “From Beyond,” written in 1920 and first published in the June 1934 issue of Fantasy Fan—so don’t be so quick to trunk your early stories. You can read it here.

Spoilers ahead.

“It is not pleasant to see a stout man suddenly grown thin, and it is even worse when the baggy skin becomes yellowed or greyed, the eyes sunken, circled, and uncannily glowing, the forehead veined and corrugated, and the hands tremulous and twitching. And if added to this there be a repellent unkemptness; a wild disorder of dress, a bushiness of dark hair white at the roots, and an unchecked growth of pure white beard on a face once clean-shaven, the cumulative effect is quite shocking. But such was the aspect of Crawford Tillinghast on the night his half-coherent message brought me to his door after my weeks of exile.”

Summary: Crawford Tillinghast should never have studied science and philosophy, for he’s no cold and impersonal investigator. He means to “peer to the bottom of creation,” a grandiose goal baffled by the feebleness of human senses. But he believes we have atrophied or rudimentary senses beyond the five we know, which certain waves might activate, and so he’s built an electrical contraption to generate the waves. When his best friend, our narrator, cautions him against the experiment, Tillinghast flies into a fanatical rage and drives him off.

Ten weeks later, Tillinghast summons narrator back to his home. Narrator’s shocked by his friend’s emaciation and dishevelment, the manic glow in his sunken eyes, the whitening of his hair. Tillinghast trembles as he ushers narrator inside and leads him to his attic lab, a single candle in his hand. Is the electricity off? No, but Tillinghast dares not use it, for reasons unspecified.

He seats narrator near his electrical machine, which glows a sickly violet. When he switches it on, the glows turns to a color or colors indescribable. That’s ultraviolet, Tillinghast declares, rendered visible to their eyes by the action of the machine. Soon other dormant senses will awaken, via the pineal gland, and they will perceive things from beyond.

Narrator’s first outre perception is that he sits not in an attic but in a temple of dead gods, with black columns rising to a cloudy height. This yields to a sense of infinite space, sightless and soundless. Narrator is spooked enough to draw his revolver. Next comes a wild music, faint but torturing. He feels the scratch of ground glass, the touch of a cold draft.

Though Tillinghast grins at the drawn revolver, he warns narrator to remain quiet. In the rays of the machine, they not only see but can be seen. The servants found that out when the housekeeper forgot his instructions and turned on the lights downstairs. Something passed through the wires by sympathetic vibration, and then there were frightful screams. Later Tillinghast found three heaps of empty clothes. So narrator must remember — they’re dealing with forces before which they’re helpless!

Though frozen in fear, the narrator grows more receptive. The attic becomes a kaleidoscopic scene of sense-perceptions. He watches shining spheres resolve into a galaxy shaped like Tillinghast’s distorted face. He feels huge animate things drift past or through his body. Alien life occupies every particle of space around the familiar objects in the attic; chief among the organisms are “inky, jellyish monstrosities,” semi-fluid, ever-moving—and ravenous, for sometimes they devour each other.

The jellies, Tillinghast says, flounder around and through us always, harmless. He glares at narrator and speaks with hatred in his voice: Tillinghast has broken barriers and shown our narrator worlds no living men have seen, but narrator tried to stop him, to discourage him, was afraid of the cosmic truth. Now all space belongs to Tillinghast, and he knows how to evade the things that hunt him, that got the servants, that will soon get narrator. They devour and disintegrate. Disintegration is a painless process—it was the sight of them that made the servants scream. Tillinghast almost saw them, but he knew how to stop. They are coming. Look, look! Right over your shoulder!

Narrator doesn’t look. Instead he fires his revolver, not at Tillinghast but at his cursed machine. It shatters, and he loses consciousness. Police drawn by the shot find him unconscious and Tillinghast dead of apoplexy. The narrator says as little about his experience as possible, and the coroner concludes that he was hypnotized by the vindictive madman.

Narrator wishes he could believe the coroner, for it now unnerves him to think about the air around him, the sky above. He cannot feel alone or comfortable, and sometimes a sense of pursuit oppresses him. He can’t believe it was mere hypnotism, though, for the police never do find the bodies of the servants that Tillinghast supposedly murdered.

What’s Cyclopean: The adjectives this week are used well and in moderation.

The Degenerate Dutch: We avoid distressing glimpses of Lovecraft’s many prejudices this time out, thanks to the tight focus on the narrator’s relationship with Tillinghast.

Mythos Making: There’s no overt connection with the creatures and structures of the Mythos, but Tillinghast’s machine unquestionably reveals the terrible spaces through which Brown Jenkins travels, from which the Color comes, in the heart of which a monotonous flute pipes and Azathoth blazes. It’s all here, waiting.

Libronomicon: Tillinghast’s research doubtless draws on a fascinating library, which we unfortunately don’t see.

Madness Takes Its Toll: And Tillinghast has paid that toll.

Anne’s Commentary

This is the rare Lovecraft story I remember reading only once; while the inky jellies and hunter-disintegrators have their appeal, Crawford Tillinghast struck me as a total jerk. Definitely not someone I wanted to visit again. Our narrator’s more tolerant, perhaps due to our favorite emotional combo of repulsion and fascination. To be fair, Tillinghast might have been a decent guy before he became “the prey of success” (sweet turn of phrase) and started deteriorating into grandiose madness. Still, narrator got all the Lovecraftian warning signs of friend-turned-big trouble: barely recognizable handwriting, alarming physical changes, a hollow voice. Plus whitened hair and uncannily glowing eyes. Ocular glare is the surest sign of dangerous fanaticism in the Mythos world.

I do like the name “Tillinghast,” which is quintessentially Rhode Island. I wonder if Crawford was related to Dutee Tillinghast, whose daughter Eliza married Joseph Curwen. Probably, in which case he might have inherited Curwen’s affinity for cosmic horror.

In any case, “From Beyond” contains many fore-echoes. There’s the strange music narrator hears, like the music with which Erich Zann became so familiar. There’s the unplaceable color Tillinghast’s wave-generator emits. Tillinghast calls it ultraviolet, but it also looks forward to that even more ominous color outside Arkham, and narrator ends up with a chronic anxiety about the air and the sky. More important, this story is an early example of Lovecraft’s overarching fictional premise. Close to mundane reality – too close for the comfort of the preternaturally perceptive and recklessly curious – are myriad other realities. Some can be entered via the altered mental state of sleep, as in the Dreamlands tales. Some are accessible via applied hypergeometry, as in “Dreams in the Witch House” and last week’s “Hounds of Tindalos.” Past and future realities are the playground of time-masters like the Yith and all those who hold the necessary keys, silver or otherwise. Most terrifying are the hidden subrealities of our own continuum. You know, Cthulhu napping under the Pacific, and ghouls burrowing under Boston. Yuggoth fungi sojourning in Vermont. Yith marking up books in our great libraries. Deep Ones in Innsmouth, and shoggoths in the Antarctic, and flying polyps in Australia, and immortal wizards in Providence. And, and, and!

And, in “From Beyond” itself, those normally invisible jelly-amoebas which are always with us and those hunters which are always nearby and which, given proper conduits, do away with Tillinghast’s servants. Foreshades of the Tindalos hounds! I guess that these entities haunted me as they do our narrator, though semi-subconsciously, because on rereading I’m struck by the appearance their close relations make in my novel Summoned. Miskatonic University archivist Helen Arkwright takes a vision-enhancing potion to assist her in plumbing magically obscured marginalia in the Necronomicon. However, she’s distracted from the sacred book when she notices what swarms the rare book vault – what presumably swarms it all the time, unseen. Lean translucences with dozens of appendages, with which they climb up and down in the air. Gossamers whose feathery antennae yearn toward her with avid curiosity. One lands on her back. When she tries to crush it against the wall, it oozes whole through her chest, unharmed.

She realizes the gossamers are harmless, but her hypervision also detects patches of ethereal fabric that separate the vault from some very other place, against which something heaves an enormous gelatinous haunch and peers with glinting and clustered eyes.

Sounds hunterish to me. Good thing for Helen that if MU has acquired Tillinghast’s wave-generator, it hasn’t stored it in the tomes vault. Otherwise my deep memory would doubtless have had her stumble into the machine and turn it on, unleashing the things with the haunches and eyes. In which case my book would have ended neither with a bang nor a whimper, but with a resounding “Aaaaaaaaaaaaaagh—”

Ruthanna’s Commentary

Damn. This story would have delighted me any week, but it contrasts particularly sharply with last week’s “Hounds of Tindalos.” They have pretty much the same plot, save that Chambers is a jerk and Tillinghast is a murderous jerk. But where Long—or his narrator—wants to tell you at length about the metaphysical explanations for his enhanced perceptions, Lovecraft and Tillinghast show. Picture it now: the colors writhing just beyond vision, eager to be seen; the ghostly jellyfish moving around and through you, tentacles brushing your cheek… and the things that Tillinghast doesn’t see till the last, and so never shows or describes. Better not look behind you! Keep still. Don’t blink.

For once, one of Howard’s stories benefits from being the trope-maker. In later stories, he’ll depend at least somewhat on repetitive set pieces to try and invoke this same mood. The monotonous flute, the mindless gods, the non-Euclidean geometry… but every description here is new, and wildly strange, and so far as I can recall never gets reused. The end result convinces me that I really would be tempted to look, and that it really would be a terrible idea.

And the language is terrific, ornate enough to be evocative without going over the top. Not that I don’t love me some over-the-top Lovecraft, but: the jellyfish and other strange fauna are “…superimposed upon the usual terrestrial scene much as a cinema view may be thrown upon the painted curtain of a theatre.” I can imagine it perfectly—alas that the art coming up in an image search doesn’t seem to have taken the dare.

I find the psychological conceit here fascinating, even if Lovecraft framed it in a way that makes little sense by modern standards. Do we have atrophied and rudimentary senses that could be enhanced to show more of reality? Sort of. Scent’s a good candidate—we have less than most other mammals, and a good portion of what we get is non-conscious. The jelly-thing-sensing organ is less likely. The pineal gland—fallback explanation for unlikely abilities since Descartes—honestly has enough to do keeping everyone’s hormones in order, without also connecting us to reality’s other layers.

But humans are obsessed with expanding their senses, and it turns out we’re really quite good at it. You can get glasses that will let you pick up infrared (although it’ll look like an ordinary glowing light, sorry), or cataract surgery to see ultraviolet. Better yet, wear a belt that always vibrates at magnetic north, and within a few days you’ll have integrated a directional sense in with the sense you come by naturally. Then there are the people who implant magnets in their fingertips—I don’t think my keyboard would like it, but it’s tempting. Some of the more outre compensations for blindness involve translating the input from a camera into stimulation of the back or tonguea—visual input turns to touch, and given a little bit of time to adjust, the occipital lobe will use the new input as happily as it would the standard signals from rods and cones.

So if we actually had Tillinghast’s machine, it’s likely that we’d find a way to process the strange sense of the beyond as ordinary vision and hearing. And while it might be a bit creepy at first, I suspect we’d learn how to get along with it pretty well, after all. Humans are good at processing whatever we can get into our brains, and we’re always hungry for more.

Next week, Lovecraft warns us about the dangers of meddling in wetlands—no, not the ones near Innsmouth—in “The Moon-Bog.”

Ruthanna Emrys’s neo-Lovecraftian novelette “The Litany of Earth” is available on Tor.com, along with the more recent but distinctly non-Lovecraftian “Seven Commentaries on an Imperfect Land and “The Deepest Rift.” Her work has also appeared at Strange Horizons and Analog. She can frequently be found online on Twitter and Livejournal. She lives in a large, chaotic household—mostly mammalian—outside Washington DC.

Anne M. Pillsworth’s short story. “The Madonna of the Abattoir” appears on Tor.com, and her first novel, Summoned, is available from Tor Teen. The second in the Redemption’s Heir series, Fathomless, will be published in October 2015. She lives in Edgewood, a Victorian trolley car suburb of Providence, Rhode Island, uncomfortably near Joseph Curwen’s underground laboratory.

“From Beyond” is an intriguing and likeable early experiment in perceiving and depicting hidden realities.

Weird Tales: The first appearance was in June 1934 issue of The Fantasy Fan, also found in this issue are sometime client R. H. Barlow’s “The Little Box”, Clark Ashton Smith’s poem “The Muse of Hyperborea”, the ninth part of “Supernatural Horror in Literature” and an essay by H. Koenig on August Derleth’s favorite weird stories. It appeared in Weird Tales in February 1938, along with Lovecraft and William Lumley’s “The Diary of Alonzo Typer”, Robert E. Howard’s sonnet “Haunting Columns”, Henry Kuttner’s “World’s End” and the second part of Manly Wade Wellman’s Judge Pursuivant story “The Hairy Ones Shall Dance”.

I don’t know. I’m rather less enamored of this story than either of our rereaders or Joshi, for that matter. I found it to be rather a plod. Certainly, there are elements which HPL will use later on to much better effect, but this is another of those works that seems to fall between juvenilia and writer with some real command of his craft.

Another story that I see having pieces of this one is “The Shunned House”, with Tillinghast taking on the role of the narrator’s uncle. The fact that the narrator here faces, however briefly, some potential legal consequences further highlights the lack of same in “House”.

Lovecraft was ahead of his time with what I see as the main message of this story. What’s the most important thing we learn from Tillinghast’s ultraviolet light machine that modern science wouldn’t appreciate till years later?

Sunlamps are dangerous and can kill you, that’s what.

Ellynne @@@@@ 3 Hmm, Tillinghast as radiation poisoning sufferer. The kind of radiation poisoning that makes your eyes glow! That might, with enough time, bring on strange somatic and mental mutations! Too bad apoplexy got him first.

No love for the 1986 film version? It was basically a followup to their version of ‘Re-Animator.’

AMPilssworth @@@@@ 4 Exactly!

Does anyone know if Lovecraft ever read Toilers of the Sea by Hugo? In one of the chapters, A Fit Tenant for a Haunted House, we’re told that one of the characters, Gilliatt, believes the air may be full of invisible creatures.

Not that I usually think of Victor Hugo and Lovecraft having much in common. But, except for the “wise Creator,” it sounds like something Lovecraft might say. Only, “many things would be made clear” doesn’t sound sinister enough when Hugo says it.

The movie adaptation is hands down the best HP Lovecraft film adaptation ever. While it had the same cast and crew as Reanimator, it was much darker and really captured the descent into madness you expect from HP. Barbara Crampton’s final scene is awesome.

@6: I’m not sure whether he read that particular story: in a discussion of the French weird tradition, “Supernatural Horror in Literature” briefly mentions “such tales as Hans of Iceland” but overall compares the supernatural tales of Hugo and Balzac unfavourably to those of Théophile Gautier.

I don’t think you need to go back all the way to Victor Hugo. Two much more probable sources would be Ambrose Bierce’s 1893 story “The Damned Thing” (invisible monster kills people, with a seeming preference for people who become aware of it) and/or Guy Maupassant’s 1886 story “The Horla” (invisible monster, probably extraterrestrial, probably intelligent, kills people with a seeming preference for etc.).

If memory serves, there was a long debate about whether the Bierce story was copying from / inspired by the earlier Maupassant. I don’t know if it was ever resolved. But there’s no question that Lovecraft read the Maupassant story; he mentions it on more than one occasion.

— Maupassant was an absolutely wonderful short story writer. Like Lovecraft, he died in his forties, his career tragically cut short by syphilis. And like Lovecraft, he started a number of tropes that are still going strong today. He’s still very much worth reading today. Mind, a lot of his stories involved S – E – X to a degree that, while very mild today, would probably have caused Lovecraft to swallow hard.

Doug M.

1) This story creeped me the hell out as a kid.

2) Despite being written in 1920, it’s clearly a mid-period work; the prose may be florid, but it’s assured, and the story is a fine-tooled machine. You may argue with this adjective or that, but there really isn’t any fat in this one; it’s exactly as long as it needs to be. Sometimes it’s easy to forget what a competent craftsman HPL was, but it really shows here.

3) There’s a recent (like, six months ago?) anthology of stories based on this — _Resonator_, edited by Scott R. Jones, from Martian Migraine Press. It includes a story by my good friend Leeman Kessler, who is also famous as the man behind the Ask Lovecraft videos. (And if you’re not familiar with Ask Lovecraft, your life is not complete. They’re all on YouTube, free. Just go.)

Doug M.

I have a series of tangentially related posts so bear with me.

As an indicator of HPL’s pervasive popularity these days, NecronomiCon is taking place in just a few short weeks in Providence , RI.

http://necronomicon-providence.com/enter/

The program looks excellent and varied, and passes are still available. I am editing an anthology that will hopefully debut there. I am not shilling for that book right now (won’t even mention the title), but while I was writing my introduction I was trying to get a handle on what is the current status of Cthulhu mythos/Lovecraftian (whatever word you want) publication these days and realized I didn’t have an idea. So I went through my own library. Amazon and a few other sources and complied a list of printed books in this vein published beginning in 2010, about when the tsunami of material became unmanageable. I did not include children’s/picture books, nonfiction references, art books, comic book/graphic novels, chap books or collections where there was maybe one Lovecraftian story. There is no pretense that this is a complete list. I was even more taken aback than I expected to by the sheer volume. Anyway, if the editor indulges me, I’ll list them in the next few posts.

ANTHOLOGIES

Black Wings 1 ed Joshi

Black Wings 2

Black Wings 3

Black Wings 4

Innsmouth Nightmares ed Gresh

That is Not Dead ed Schweitzer

The Starry Wisdom Library ed Pederson

Lovecraft’s Monsters ed Datlow

The Book of Cthulhu ed Lockhart

The Book of Cthulhu 2 ed Lockhart

New Cthulhu: The Recent Weird ed Guran

New Cthulhu 2: More Recent Weird ed Guran

Jazz Age Cthulhu (3 novellas)

Shadows Over Main Street: An Anthology of Small-Town Lovecraftian Terror

Madness on the Orient Express: 16 Lovecraftian Tales of an Unforgettable Journey

Atomic-Age Cthulhu: Tales of Mythos Horror in the 1950s

Beyond the Mountains of Madness ed Price

World War Cthulhu: A Collection of Lovecraftian War Stories

Steampunk Cthulhu: Mythos Terror in the Age of Steam

Eldritch Chrome: Unquiet Tales of a Mythos-Haunted Future

Space Eldritch

Space Eldritch II: The Haunted Stars

Techno-Goth Cthulhu ed Crittenden

Shot Guns vs Cthulhu

That Ain’t Right: Historical Accounts of the Miskatonic Valley (Mad Scientist Journal Presents) (Volume 1)

Strange Versus Lovecraft: A Strange Anthology

Weirder Shadows Over Innsmouth ed Jones

The Dark Rites of Cthulhu ed Sammons

Deepest Darkest Eden ed Goodfellow

Dark Fusions: Where Monsters Lurk ed Gresh

In the Court of the Yellow King ed Barrass

The Children of Old Leech: A Tribute to the Carnivorous Cosmos of Laird Barron

The Madness of Cthulhu Vol 1 ed Joshi

The Madness of Cthulhu Vol 2 ed Joshi

The Fall of Cthulhu

The Fall of Cthulhu, volume 2

Cthulhu Lives!: An Eldritch Tribute to H.P. Lovecraft

Whispers from the Abyss ed Rocha

Delta Green: Through a Glass Darkly by Detwiller

Cthulhu Passant ed Herman

The Aklonomicon ed Pulver and McCann

A Mountain Walked ed Joshi

New Tales of the Old Ones ed Dick

The Grimscribe’s Puppets ed Pulver

Cthulhurotica ed Cuinn

Swords Against Cthulhu ed Chappell

Dead But Dreaming 2 ed Ross

The Shadow of the Unknown ed French

Worlds of Cthulhu ed Price

A Season in Carcosa ed Pulver

Cthulhu Cymraeg ed Jones

Future Lovecraft ed Moreno-Garcia and Stiles

Fantastic Horror Vol 5: The Mythos Revisited Stevens

Dark Tales from Elder Regions: New York ed Burge, Burke

Delta Green: Tales from Failed Anatomies ed Detwiller

Letters to Lovecraft ed Bullington

New Tales of the Yellow Sign ed Laws

Swords & Mythos ed Moreno-Garcia and Stiles

Cthulhu Deep Down Under ed Proposch, Sequeira, Stevens

Shadow’s Edge ed Stranzas

Cthulhu Unbound 3

Cumbrian Cthulhu 1-4 McGuigan

Urban Cthulhu: Nightmare Cities Harksen

The Call of Lovecraft ed Norris

Torn Realities Anderson

The Outsiders ed Mynhardt

Historical Lovecraft: Tales of Horror Through Time ed Moreno-Garcia, Stiles

Cosmic Horror Anthology

The Yith Cycle ed Price

Dreaming in Darkness ed Prescott

Resonator ed Jones

Conquerer Womb: Lusty Tales of Shub Niggurath

Lovecraft Unbound ed Datlow

SINGLE AUTHOR COLLECTIONS

The Shadow Out of Providence Claverie

The Whispering Horror Bertin

In the Gulfs of Dream and Other Lovecraftian Tales Barker, Pugmire

The Gaki & Other Hungry Spirits Rainey

Hex Code and Others Mayers

The Engines of Sacrifice Chambers

Dark Melodies Meikle

Bohemians of Sequa Valley Pugmire

Of Gods & Aliens Cartwright

Lovecraftian Covens Seawright

A Pretty Mouth Tanzer

Uncommon Places: A Collection of Exquisites Pugmire

Things Yet Undreamed: Mythos Tales Fischer

Best Little Witch House in Arkham McLaughlin

Through Dark Angles Webb

Shades of Lovecraft Melniczek

The Inhabitant of the Lake and Other Unwelcome Tenants Campbell

Visions from Brichester Campbell

Goat Mother and others Comtois

Mists of the Miskatonic: Tales Inspired by the works of H.P Lovecraft by Halsey

The Nikronomicon by Mamatas

The Lovecraft Coven by Tyson

Burnt Black Suns by Stranzas

The Lord Came at Twilight by Mills

The Wide Carnivorous Sky by Langan

The Beautiful Thing That Awaits us All by Barron

Unseaming by Allen

The Altar In The Hills and Other Weird Tales by Barrows

The Revnant of Rebecca Pascal Pugmire/Barker

Ghouljaw and Other Stories Smith

Some Unknown Gulf of Night Pugmire

The Lurkers in the Abyss and Other Tales of Terror by Riley

Two Against Darkness Barras and Shiflet

Lovecraft’s Pillow Faig

Shadows from Norwood Hambling

The Country of the Worm: Excursions from Beyond the Wall of Sleep Myers

Secret Hours Cisco

Eldritch Evolutions Gresh

Nightmares from a Lovecraftian Mind Krall

The Alchemist’s Notebook Craft

A House of Hollow Wounds Pulver

Teatro Grottesco Ligotti

The King in Yellow Tales Vol 1 Pulver

Encounters with Enoch Coffin Pugmire/ Thomas

The Strange Dark One Pugmire

Sin & Ashes Pulver

Portraits of Ruin Pulver

Keyport Cthulhu Rosamilia

Gray Magic: An Episode of Eibon Myers

Gears of a Mad God Omnibus Nichols

Beneath the Surface Stranzas

Midnight Call and Other Stories Thomas

13 Conjurations Thomas

The Lonely Shadows Glassy

The Green Lama Unbound Garcia

The Black Lake Rodger

A Christmas Cthulhu Griffiths

Tentacle Death Trip Krall

The Dark Boatman Glasby

The Legacy of Erich Zann Stableford

The Cthulhu Encryption Stableford

The Four Corners of the Tapestry: The Casebook of Palmer Hopkins Lobdell

Their Hand is at Your Throats: Stories After Lovecraft Shire

The Coming of Winter Cartwright

Gretchen’s Wood Cartwright

That Hideous Thing Cartwright

The Friendly Horror & Other Weird Tales Burdge, Burke

Re-Animated States of America Mullins

NOVELS/NOVELLAS

In the Lovecraft Museum novella by Tem

The Last Revelation of Gla’aki novella by Campbell

The Weird Company: The Secret History of H. P. Lovecraft’s Twentieth Century by Rawlik

Reanimators by Rawlik

Red Equinox by Wynne

The Assaults of Chaos: A Novel about H. P. Lovecraft by Joshi

The Croning by Barron

The Return by Riley

That Which Should Not Be Talley

He Walks in Shadows Talley

The Orphan Palace Pulver

The Annihilation Score Stross

Equoid Stross

The Rhesus Chart Stross

The Apocalypse Codex Stross

The Fuller Memorandum Stross

Carter & Lovecraft Howard

The Weird Shadow Over Morecambe: A Cthulhu Mythos Novel Glasby

The Hungering God Bligh

The Dweller in the Deep McNeil

Bones of the Yopasi McNeil

Ghouls of the Miskatonic McNeil

The Lies of Solace French

Feeders from Within Evans

The Sign of Glaaki Saville, Lockley

Dance of the Damned Bligh

The Plasm Meikle

The Stars Were Right Alexander

Old Broken Road Alexander

Southern Gods Jacobs

The Trials of Obed Marsh: A Prequel to Lovecraft’s A Shadow Over Innsmouth Davenport

The Creeping Kelp Meikle

The Dreamquest of Unknown Kadath (Revisited) Keffer

Gaia’s Lament Howard

Mask of the Other Stolze

Dante’s Fool Rodger

14 Clines

The Damned Highway Keene, Mamatas

Houdini & Lovecraft: The Ghostwriter Wilkerson

The Natural Dissolution of Fleeting-Improved-Men (the Last Letter of HP Lovecraft) Blackwell

Ever Has Night Gone D’Champ

Interlands O’Neil

Realm Hunter: Pursuit of the Silver Dirk Greenwade

Awoken Elinsen

The Color over Occam Thomas

Dread Island Lansdale

The Eerie Adventures of the Lycanthrope Robinson Crusoe Clines

Maplecroft Priest

The House in the Port Torina

Dyatlov Pass Baker

Lucky’s Girl Holloway

Whom the Gods Would Destroy Hodge

The Express Diaries Marsh

Revival King

Elder Signs End Times Trilogy Book One: Arkham Stanfield

Deadtown Abbey Hoade

Caverns of Chaos D’Ammassa

The Haunter of the Threshold Lee

The Secret of Merrow’s Bay Perry

Playtime for Cthulhu Stevens

Catastrophic Discoveries Ness, Brown

The Gods of Miskatonic Hill

Oakfield Rodger

The Dunfield Terror Meikle

At the Mountains of Madness Davenport

The Old One Douglas

When the Stars Are Right Cartwright

Winter Falls Skelson

The Womb of Time Stableford

@14: A new Lovecraftian novella from Tor.com’s imprint has just been announced, Kij Johnson’s “The Dream-Quest of Velitt Boe”.

MTCarpenter @@@@@ 11 et alia An impressive list of tomes, there!

I hope to be at Necronomicon and will look for your anthology.

DougM @@@@@ 10: Given the 14-year gap between writing and publication, I wonder if he might not have done some serious editing before sending it out.

Can anyone report on The Weird Shadow Over Morecambe: A Cthulhu Mythos Novel Glasby? I’ve ended up using “Morecambe County” as the in-universe name of the county in which Arkham et al. are located, for the reason that Morecambe, England seems extremely Lovecraftian–there being some inhabited parts that become entirely inaccessible at the highest tides. Very curious what Glasby has done with it.

Not making it to Necronomicon this year, alas. Maybe next year, when it’ll be a little easier to make arrangements for the spawn.

@10: I had not previously encountered “Ask Lovecraft”: correcting this oversight has proved entertaining. Thank you for mentioning it.

@17: A blurb:

Professor Mandrake Smith would be unrecognisable to his former colleagues now, but the shambling, drink-addled former Professor of Anthropology at Oxford is now barely surviving in Morecambe. Here he has many things to forget, although some don’t want to forget him. Plagued by the nightmares of his past, both in Oxford and Papua New Guinea, he finds himself dragged into a morass of supernatural activity centered around the deposition of filleted corpses in the ancient rock-cut graves at St. Patrick’s Chapel, Heysham Head. Unwillingly drafted into helping the enigmatic Mr Thorn, he grudgingly assists in trying to stop the downward spiral into darkness and insanity that awaits Morecambe, and then the entire world…

Of course, in Britain Morecambe also has some less eldritch associations…

ETA: An upcoming television series of potential interest: Herald.

One of the methods in which humans enhance their senses is by taking psychedelic drugs. I imagine that some psychonauts have had bad trips similar to what Lovecraft describes here. And the pineal glamd may or may not release small amounts of DMT, the most powerful psychedelic substance known to man, in moments of joy.

As for why some people look down on Lovecraft’s prose, I can think of a few reasons. Which I’m sure have been brought up elsewhere.

* It’s CURRENT YEAR! Politics matters, sometimes justly (we don’t need the casual racism in, say, “Cats of Ulthar”) but sometimes unfairly (like where there isn’t racism but we’ve primed ourselves to look for it anyway, like Alhazred being sardonically tagged an “indifferent Moslem” by contrast with his peers in the late-Umayyad Damascene elite).

* For better or worse, Cthulhu is the most iconic of Lovecraft’s beasties; this means readers start with Call Of Cthulhu, which is a difficult read, at least until Rlyeh rises up.

* Those of us who moved on to the good stuff – like this one, and Colour Out Of Space – often found such tales in anthologies, mixed in with the dreck. The scramble robbed us of a feel for how Lovecraft evolved as a writer. Compare with how wonderfully Nightshade Press has handled Clark Ashton Smith.

* Lovecraft fancied himself not just an author, but foremost a poet, like Klarkash-Ton and Lord Dunsany. So he attempted lyrical flourishes in several tales. Since his poetry was mostly ass this has yielded VERY mixed results. For instance I thought “Cats of Ulthar” was fine, until I tried reading it out loud to an audience…

The notion that a mysterious organ in the brain allows for ESP has cast a long shadow through sci-fi. I’m currently re-(re-re-re-)playing Alien Legacy. You colonise a couple of Earth-like planets inhabited by primitive animals, no sentients. But they all share a curious extra lobe in the brain that seems to do nothing. But then an alien probe wakes up in the asteroid-belt. Guess what the animals do next!

I realize this is a very late addition, but I came across a historical tidbit that I thought was worth mentioning. This article describes an anecdote that Lovecraft related in an article he wrote for a local newspaper:

The name Tillinghast obviously jumped out at me, so I tried to find further information, and discovered this article which describes a hoax perpetrated by Mr. Tillinghast in December 1909. In short, he claimed to have designed and secretly flown a prototype airplane for several hundred miles. The press and public were taken in for a month or so, with several “sightings” of the craft being reported by various people, until the story eventually unraveled due to a lack of hard evidence.

Given this, it seems highly likely that Lovecraft named his mad scientist as a dig at the real Mr. Tillinghast (he seems to have had a low opinion of the hooplah surrounding the story). However, I can only find one webpage that points out the connection. Is this just considered such common knowledge among Lovecraft enthusiasts that it goes without saying?

That’s awesome! It’s always fun to find these tuckerizations, and it certainly wasn’t common knowledge for this particular Lovecraft enthusiast.

Another early story which presented the existence of a wide variety of creatures moving amongst us which our senses can’t perceive was J.H. Rosny Aine’s 1895 story “Un Autre Monde” (Another World). The narrator is a mutant who has quite a number of other anomalies, including hearing and seeing in other frequencies than is usual for humans. All his life he’s seen the creatures, but it took a few years before he realized no one else did. The creatures themselves are also unaware of us and pass easily through material objects. The story was translated for Damon Knight’s anthology A Century of Science Fiction.

There was also another, more recent, even looser adaptation titled Banshee Chapter. Rather than some sort of machine, this one ties the ability to see Beyond to DMT and the MKUltra project. It’s not great, about one step above your average Found Footage horror flick, but it does have a fairly entertaining Hunter S. Thompson-esque writer, and Katia Winter plays the lead and does the best she can with the material she has to work with.

In addition, the heavy metal band Manilla Road did a song, based mostly on the movie from what I can tell, called From Beyond, on their album The Courts of Chaos. It’s pretty good, and there’s also one called Dig Me No Grave on the album, but it unfortunately doesn’t have anything other than the title in common with the Robert E. Howard story.

This story reminds me of the opening to the Great God Pan – mad scientist uses a device to peer beyond the veil, with disastrous consequences.