Chase scenes are usually exquisitely boring. What do they have to offer, really, but a parade of frenzied verbs, like an aerobics instructor bellowing moves at a class? “Leap over that rusted-out Mercedes! Now pivot and punch that harpy right in the jaw! Right in the jaw! Good! Now her flock is descending from the filthy sky of Los Angeles in a swirl of fetid wings! Turn around and run! Dive under that garbage truck! Now roll! Roll faster!”

Okay, fine. You got away from the harpies, hero, only to see Esmerelda borne off in their talons, weeping. Now we can all get to the good part, where you brood over how you’ve failed her, just the way your father failed you. You can think things, feel things, and actually manifest character rather than just slugging away at the forces of evil. A chase scene can seem like a kind of literary homework, the writer providing obligatory action to placate readers. This is very exciting. Isn’t it? The harpy’s electrified blood sends a jolt through the Blade of Lubricity and nearly shorts out its enchantment. Whatever.

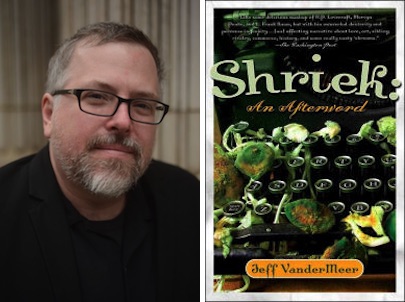

So when there is a chase scene that actually knots my entrails with dread and courses me with icy terrors, I’m going to look closely at how the writer pulled it off. Which brings me to Jeff VanderMeer’s Shriek: An Afterword and one of the freakiest chase scenes of all time.

We’re in Ambergris, a city of fungus and rot, a city founded on the incomplete genocide of a race of inhuman mushroom people, the gray caps, the survivors now living underground. It’s the night of the annual Festival of the Freshwater Squid, when things often go horribly wrong, even in peacetime, which this is not. Janice and Sybel are barricaded in her apartment, waiting for the night to pass, when something scratches at her door. They decide to crawl out the bathroom window before that something can get in, and it pursues them.

Put it like that, and it might sound like more of the same old verbfest, leap and dart and collide. Add VanderMeer’s storytelling, though, and it’s tense to the point of nausea. Why?

For one thing, he takes his time building up that tension; the pacing leading into the chase scene is positively languid. He begins the chapter with Janice telling us just how dreadful everything is about to be: “There came the most terrible of nights that could not be forgotten, or forgiven, or even named.” Then Janice and her brother Duncan spend several pages changing the subject, twisting us through ornate digressions. It’s an old trick, maybe, but it totally works. “Janice, c’mon! Tell us already!”

We spend more time peering out a window and coming to an understanding of just how bad things are getting outside, and just how much we might prefer not to leave the apartment: “Then a man came crawling down the street, shapes in the shadows pulling at his legs. Still he crawled, past all fear, past all doubt. Until, as the Kalif’s mortars let out a particularly raucous shout, something pulled him off the street, out of view.”

Okay, yikes. I admit to a general flesh-creep at this point. What would it take to make you run outside, having seen that? Aren’t there Buffy reruns to watch? Anything?

After another extended swerve to recount Duncan’s adventures at the time, we learn what it takes. First the something scratches—always a nice touch, soft and insinuating, like ghost-Catherine’s scrabbling on the windowpane at the beginning of Wuthering Heights—and then it knocks. And then, holy crap, it speaks. “In a horrible, moist parody of a human voice, it said, ‘I have something. For you. You will. Like it’.”

This is another old trick, and a devastating one. When the uncanny leaps out and snaps its jaws at you, it’s just another bad-thing-that-happens, its ontological status not much different than a car crash’s. You can respond with simple, reflexive action: a hearty kick, perhaps. When the uncanny licks its lips and ploys its seductive wiles, when it pleads with you or lures you in or mesmerizes you, that’s when you have real problems. Your choices become two: a sliding into complicity, or the desperate revulsion that shoves complicity away just as hard as it can. An emotional movement precedes the physical ones.

This is when Janice and Sybel decide to risk the night, rather than wait for the something—which has surely overheard them talking about their escape route—to batter down the door. As they climb out the window, “the banging behind me had become a splintering,” accompanied by a “gurgling laugh” and the insistent claim that the thing has something for them they’ll really, really like. And even in the frantic chase over the rooftops that follows, VanderMeer takes time out from the action to layer on the eerie atmospherics: the smell “like rotted flesh, but mixed with a fungal sweetness;” the leap over a gap between buildings with “the ground spinning below me, the flames to the west a kaleidoscope;” the still-unseen something savoring their scent as it draws close. The warping of time that makes our most dreadful moments seem to hang on forever is enacted, word by word, on the page.

We’ve made such a fetish of keeping up the pace in writing, but the real excruciation can come from lingering. We’ve come to a wall, and a thing “with eyes so human and yet so various that the gaze paralyzed me” is almost on top of us, and there’s nothing we can do.

Stay there a while. The blow can wait.

Sarah Porter is a writer, artist, and freelance teacher who lives in Brooklyn with her husband and two cats. She is the author of several books for young adults, including Vassa in the Night, soon to be published by Tor Teen.

Sarah Porter is a writer, artist, and freelance teacher who lives in Brooklyn with her husband and two cats. She is the author of several books for young adults, including Vassa in the Night, soon to be published by Tor Teen.