In this bi-weekly series reviewing classic science fiction and fantasy books, Alan Brown looks at the front lines and frontiers of the field; books about soldiers and spacers, scientists and engineers, explorers and adventurers. Stories full of what Shakespeare used to refer to as “alarums and excursions”: battles, chases, clashes, and the stuff of excitement.

My mission in this column is to look at older books, primarily from the last century, and not newly published works. Recently, however, an early and substantially different draft of Robert Heinlein’s The Number of the Beast was discovered among his papers; it was then reconstructed and has just been published for the first time under the title The Pursuit of the Pankera. So, for a change, while still reviewing a book written in the last century, in this column I get to review a book that just came out. And let me say right from the start, this is a good one—in my opinion, it’s far superior to the version previously published.

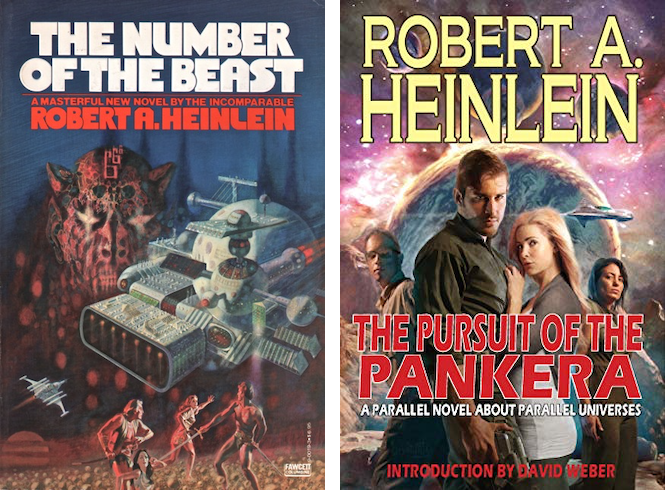

The Number of the Beast first appeared in portions serialized in Omni magazine in 1978 under the editorial direction of Ben Bova. Bova had recently finished a stint editing Analog as the first editor to follow in the footsteps of John W. Campbell. Omni published a mix of science, speculation on parapsychology and the paranormal, and fiction; a slick and lavishly illustrated magazine, it unfortunately lasted less than twenty years. The book version of Heinlein’s novel was published in 1980. My copy is a trade paperback, which was a new format gaining favor at the time, gorgeously illustrated by noted artist Richard M. Powers. While the cover is not his best work, the interior illustrations are beautifully done.

No one knows exactly why Heinlein abandoned the original version of his book, although that version draws heavily on the works of Edgar Rice Burroughs and E. E. “Doc” Smith, and there may have been difficulties in gaining the rights to use those settings.

On my first reading of The Number of the Beast, I was excited by the prospect of reading a new Heinlein work, but also a bit apprehensive, as I had not generally enjoyed his late-career fiction. Where Heinlein’s earlier published works, especially the juveniles, had been relatively devoid of sexual themes, the later books tended to focus on the sexual rather obsessively, in a way I found, to be perfectly frank, kind of creepy. I remember when I was back in high school, my dad noticed that I had picked up the latest Galaxy magazine, and asked which story I was reading. When I replied that it was the new serialized Heinlein novel, I Will Fear No Evil, he blushed and offered to talk to me about anything in the story that troubled me. Which never happened, because I was as uncomfortable as he was at the prospect of discussing the very sexually oriented story. Heinlein’s fascination with sexual themes and content continued, culminating with the book Time Enough for Love—which was the last straw for me, as a Heinlein reader. In that book, Heinlein’s favorite character Lazarus Long engages in all sorts of sexual escapades, and eventually travels back in time to have an incestuous relationship with his own mother.

About the Author

Robert A. Heinlein (1907-1988) is one of America’s most widely known science fiction authors, often referred to as the Dean of Science Fiction. I have often reviewed his work in this column, including Starship Troopers, Have Spacesuit—Will Travel, The Moon is a Harsh Mistress and Citizen of the Galaxy. Since I have a lot to cover in this installment, rather than repeat biographical information on the author here, I will point you back to those reviews.

The Number of the Beast

Zebadiah “Zeb” John Carter is enjoying a party hosted by his old friend Hilda “Sharpie” Corners. A beautiful young woman, Dejah Thoris “Deety” Burroughs, introduces herself to him, and they dance. He is impressed by her, compliments her dancing and her breasts (yep, you read that right), and jokingly proposes marriage. She accepts, and while he is initially taken aback, he decides it is a good idea. Deety had wanted Zeb to meet her father, math professor Jacob “Jake” Burroughs, who had hoped to discuss math with Zeb, but it turns out that the Burroughs had confused him with a similarly named cousin. The three decide to leave the party, and on a whim, Hilda follows them.

As they head for the Burroughs’ car, Zeb, a man of action, has a premonition and pushes them all to safety between two vehicles, as the car they were approaching explodes. Zeb then shepherds them to his own vehicle, a high-performance flying car he calls “Gay Deceiver,” and they take off. Zeb has made all sorts of illegal modifications to the air car, and is quite literally able to drop off the radar. They to head to a location that will issue marriage licenses without waiting periods or blood tests, and Hilda suddenly decides that it’s time to do something she has considered for years and marry Professor Burroughs. After the wedding, the two pairs of newlyweds head for Jake’s vacation home, a secret off-the-grid mansion worthy of a villain from a James Bond movie. (How exactly he’s been able to afford this on a college math professor’s salary is left as an exercise for the reader.) Here Zeb and Hilda discover that not only has the professor been doing multi-dimensional math, but he’s developed a device that can travel between dimensions. It turns out the number of possible dimensions they can visit is six to the sixth power, and that sum increased to the sixth power again (when the number of the beast from the Book of Revelation, 666, is mentioned, someone speculates it may have been a mistranslation of the actual number). And soon Gay Deceiver is converted to a “continua craft” by the installation of the professor’s device. While I wasn’t familiar with Doctor Who when I first read the book, this time around I immediately recognized that Gay Deceiver had become a kind of TARDIS (which had made its first appearance on the series all the way back in 1963).

Heinlein is obviously having fun with this. There are many clear nods to pulp science fiction throughout the novel, starting with the character names (“Burroughs,” “John Carter,” “Dejah Thoris”) and their connection to Edgar Rice Burroughs’ Barsoom books. The story is told through the alternating voices of the four main characters, but this literary device is not very successful, as the grammar and tone is unchanged between sections; even with the names of the current viewpoint character printed at the top of the page, it is often difficult to determine whose viewpoint we are reading. The narrative incorporates the pronounced sexual overtones that mark Heinlein’s later work, and the banter between the four would today be grounds for a “hostile work environment” complaint in any place of business in the country. They even program Gay Deceiver, who has no choice in the matter, to speak in the same unsavory manner. The women have that peculiar mix of competence and submissiveness so common in Heinlein’s work. There is also sexual tension between pretty much every character except (mercifully) Deety and her father. They adopt a nudist lifestyle at Jake’s place, and Deety’s breasts and their attractiveness are mentioned so frequently that I started thinking of them as the fifth and sixth members of the expedition.

Their idyllic stay at Jake’s house is interrupted by a visit from a Federal Park Ranger. The men—who happen to be wearing their ceremonial military swords for fun—get a bad feeling and cut the ranger down, only to discover that he is an alien being disguised as a human, whom they dub a “Black Hat.” They suspect that he was an emissary of the forces behind the car bomb at Hilda’s house, and decide they better leave. That departure turns out to be just in time, as Jake’s house is promptly destroyed by a nuclear weapon. They flit between alternate dimensions and decide to experiment with space travel, heading toward a Mars in another dimension, which Hilda jokingly dubs “Barsoom.” They find the planet, which has a breathable atmosphere, inhabited by imperialist Russian and British forces. While Zeb is initially in charge, there is bickering among the intelligent and headstrong crew, and they decide to transfer command between themselves. This produces even more difficulties, and the bulk of the book is a tediously extended and often didactic argument mixed with dominance games, only occasionally interrupted by action. The four discover that the British have enslaved a native race—one that resembles the Black Hat creatures in the way a chimpanzee resembles a human. The crew helps the British stave off a Russian incursion, but decide to head out on their own. The only thing that drives the episodic plot from here on, other than arguments about authority and responsibility, is the fact that Hilda and Deety realize they are both pregnant, and have only a few months to find a new home free of Black Hats and where the inhabitants possess an advanced knowledge of obstetrics. They travel to several locations, many of which remind them of fictional settings, even visiting the Land of Oz. There Glinda modifies Gay Deceiver so she is bigger on the inside, further increasing her resemblance to Doctor Who’s TARDIS. They also visit E. E. “Doc” Smith’s Lensman universe, a visit cut short because Hilda has some illegal drugs aboard Gay Deceiver, and fears the legalistic Lensmen will arrest and imprison them.

Then the narrative becomes self-indulgent as it [SPOILERS AHEAD…] loops back into the fictional background of Heinlein’s own stories, and Lazarus Long arrives to completely take over the action, to the point of having a viewpoint chapter of his own. Jake, Hilda, Zeb, and Deety become side characters in their own book. The threat and mystery of the Black Hats is forgotten. Lazarus needs their help, and the use of Gay Deceiver, to remove his mother from the past so she can join his incestuous group marriage, which already includes Lazarus’ clone sisters. I had enjoyed Lazarus Long’s earlier adventures, especially Methuselah’s Children, but this soured me on the character once and for all. And you can imagine my disappointment when another subsequent Heinlein novel, The Cat Who Walks Through Walls, after a promising start, was also taken over by Lazarus Long…

The Pursuit of the Pankera

The new version of the story opens with essentially the same first third as the previously published version. When the four travelers arrive on Mars, however, they find they are on the actual world of Barsoom.

Buy the Book

The Pursuit of the Pankera

They encounter two tharks, who both have strong lisps. This is not just intended to be humorous; it makes sense because of the huge tusks Burroughs described in his books. Heinlein’s delight in revisiting Burroughs’ Barsoom is palpable. It has been some years since John Carter first arrived, and he and Tars Tarkas are off on the other side of the world, fighting in less civilized parts of the planet. In his absence, Helium is ruled by a kind of triumvirate composed of Dejah Thoris, her daughter Thuvia, and Thuvia’s husband Carthoris. The Earth has developed space travel, and there are tour groups and private companies like American Express with a presence in Helium. The four protagonists discover that there was a Black Hat incursion of Barsoom at some point, which was defeated. The creatures they call Black Hats, and the Barsoomians call Pankera, are now extinct on Mars. The four find that not only are the human companies exploiting the locals, but the Earth in this dimension is infested with Pankera. They decide to share Jake’s invention with the Barsoomians, with hopes that sharing the continuum secret will give Barsoom a fighting chance both in throwing off the economic exploitation of the earthlings, and also in defeating any further Pankera efforts to infiltrate or attack Mars. And then the four adventurers must leave, because Hilda and Deety are pregnant, and Barsoom is not an ideal place to deliver and raise babies (the egg-laying Barsoomians knowing little about live births).

The four then flit between several dimensions, including Oz, in a segment that again mirrors the original manuscript. But when they arrive in the Lensman universe, they stay for a while, have some adventures, and warn the Arisians about the threat of the Pankera. Like the section on Barsoom, Heinlein is obviously having fun playing in Smith’s universe and putting his own spin on things. As with John Carter, Heinlein wisely leaves Kimball Kinnison out of the mix, using the setting but not the hero. The four travelers do not want to have their children in the Lensman universe, which is torn by constant warfare with the evil Eddorians, so they head out to find a more bucolic home.

I won’t say more to avoid spoiling the new ending. I’ll just note that while reading The Pursuit of the Pankera, I kept dreading a re-appearance of the original novel’s ending, with Lazarus Long showing up and taking over the narrative. Long does appear, but in a little Easter Egg of a cameo that you wouldn’t even recognize if you don’t remember all his aliases. In contrast with The Number of the Beast, and as is the case with so many of my favorite books, the new ending leaves you wanting more and wondering what happens next.

Final Thoughts

Sometimes when manuscripts are discovered and published after an author’s death, it is immediately apparent why they had been put aside in the first place, as they don’t measure up to the works that did see the light of day. Sometimes they are like the literary equivalents of Frankenstein’s monster, with parts stitched together by other hands in a way that doesn’t quite fit. In the case of The Pursuit of the Pankera, however, the lost version is far superior to the version originally published. It is clear where Heinlein wanted to go with his narrative, and there is vigor and playfulness in the sections where the protagonists visit Barsoom and the Lensman universe, qualities I found lacking in The Number of the Beast. The sexual themes in the newly discovered sections are mercifully toned down, as is the perpetual bickering over command authority. And the newly published version continues to follow its four protagonists right to the end, instead of being hijacked by another character’s adventures.

And now I’ll stop talking, because it’s your turn to join the discussion: What are your thoughts on both the original book, and (if you’ve read it) on the newly published version? Did the new book succeed in bringing back the spirit of Heinlein’s earlier works?

Alan Brown has been a science fiction fan for over five decades, especially fiction that deals with science, military matters, exploration and adventure.