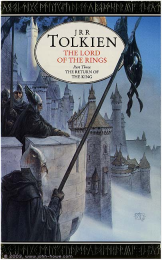

We continue the Lord of the Rings re-read with “The Ride of the Rohirrim,” chapter 5 of The Return of the King. The usual spoilers for the entire book and comments follow after the jump.

What Happens

On the fourth night of the eponymous ride, Merry and the Rohirrim are in Drúadan Forest, less than a day’s ride from the outer walls around Minas Tirith. Scouts have already reported that the road is held against them. Merry has been hearing drums and is told by Elfhelm, one of the Marshals, that the Wild Men of the Woods use them to communicate and are now offering their services to Théoden. Merry sneaks up and sees the headman, Ghân-buri-Ghân, who looks like one of the Púkel-men of Dunharrow. Ghân-buri-Ghân tells Théoden that the Riders are badly outnumbered and that, though the Wild Men will not fight, they will guide them to a forgotten road that will bypass the enemy. In return, he wants the Rohirrim to “not hunt (the Wild Men) like beasts any more.” Théoden agrees.

When the Riders come near the main road, the Wild Men tell them that the out-wall has been broken, that all attention is on the siege of Minas Tirith, and that the wind is changing; they then leave, never to be seen by the Rohirrim again. During the Riders’ rest, they discover Hirgon’s body; he appears to have been killed before he could tell Denethor that Rohan was coming.

The Rohirrim pass through the breach in the out-wall with no trouble and come near the city unnoticed. Théoden pauses, perhaps in doubt or despair; then, at a great boom (the breaking of the Gate), he springs to action, calls the Riders to battle with words and a horn-blast, and leads them forth in the morning sunlight:

darkness was removed, and the hosts of Mordor wailed, and terror took them, and they fled, and died, and the hoofs of wrath rode over them. And then all the host of Rohan burst into song, and they sang as they slew, for the joy of battle was on them, and the sound of their singing that was fair and terrible came even to the City.

Comments

I seem to be starting with chapter endings because, well, they’re right there when I come to write this section. So I’m curious what people think of this one, particularly in comparison to the last.

Me, while I know intellectually that singing in battle has a proud literary history, I just cannot believe in it. I can conceive of the emotions behind it, but if you’re fighting, don’t you need your breath?

As a more literary objection, this is the first chapter that doesn’t ratchet forward the timeline. Well, okay, technically the last chapter ends with hearing the horns, and this chapter ends a paragraph after that, but it doesn’t add anything significant. I’m sure some of my disappointment is that I know we have lots of great stuff coming up and I thought this chapter would have more in it, but all the same. Note: I haven’t re-read the next chapter yet and I’m not sure whether it contains a break point; maybe it doesn’t, in which case, oh well, can’t be helped. And I’m sure if I weren’t reading chapter-by-chapter, I’d barely notice.

* * *

This is a short chapter and is mostly about the Wild Men, the Drúedain, a name that as far as I can tell [*] appears nowhere in LotR proper but comes from Unfinished Tales. (Thanks all for reminding me of the existence of that essay, which meant I read it ahead of time for once.)

[*] While the e-book edition of LotR has a sad number of typographical errors that makes text searches less definitive than they ought to be, I didn’t see it in any of the obvious places, either.

From the description in Unfinished Tales, I was putting them down as quasi-Neanderthals: people of an entirely different kind, with short broad bodies, wide faces, heavy brows, and deep-set eyes. (I say “quasi” because I somehow doubt that there is any evidence that Neanderthals’ eyes glowed red in anger.) So I was nodding along with the description of Ghân-buri-Ghân until the end:

a strange squat shape of a man, gnarled as an old stone, and the hairs of his scanty beard straggled on his lumpy chin like dry moss. He was short-legged and fat-armed, thick and stumpy, and clad only with grass about his waist.

. . . grass about his waist? A grass skirt? Seriously? In early March, in the equivalent of Southern Europe, where Pippin is wearing a surcoat and mail without complaining of the heat? What?

I checked and there’s no mention of the Drúedain’s skin color, which means they were white, so it’s not like Tolkien was going all-out with the tropical native stereotype. But it is a really weird clothing choice.

Moving on to their language, I tried to determine something about their native tongue from the way Ghân-buri-Ghân spoke the Common Speech, but all I could get was that his language maybe didn’t use definite or indefinite articles, since he used only a few in his speech. I sometimes had the feeling that the level of grammatical sophistication varied oddly; compare “(W)e fight not. Hunt only. Kill gorgûn in woods, hate orc-folk.” with “Over hill and behind hill it (the road) lies still under grass and tree, there behind Rimmon and down to Dîn, and back at the end to Horse-men’s road.” Yes, I realize I’m wondering whether Tolkien, of all people, got a matter of language right; but I don’t know that philology actually concerned itself with the speech patterns of non-native speakers. Comments?

Finally, in return for his help, Ghân-buri-Ghân asks Théoden to “leave Wild Men alone in the woods and do not hunt them like beasts any more.” This was the weirdest thing about this entire chapter to me. Elfhelm tells Merry at the start that the Drúedain “liv(e) few and secretly, wild and wary as the beasts (and) go not to war with Gondor or the Mark.” So why are the Rohirrim hunting them like beasts? Why does Théoden not only talk to Ghân-buri-Ghân, but show absolutely no sign of thinking of him as sub- or non-human? It’s such a whiplash line that I think the story would have been better off without it.

Anyway. Tidbits from Unfinished Tales: in prior days, they were loved by the Eldar and the humans they lived among. They are astonishing trackers, never became literate, had a “capacity of utter silence and stillness, which they could at times endure for many days on end,” and were talented carvers. They were thought to have magical abilities, such as the ability to infuse watch-stones carved in their images with their power: one watch-stone was said to have killed two Orcs who attacked the family it was guarding. They have terrific laughs. According to a note of Tolkien’s,

To the unfriendly who, not knowing them well, declared that Morgoth must have bred the Orcs from such a stock the Eldar answered: “Doubtless Morgoth, since he can make no living thing, bred Orcs from various kinds of Men, but the Drúedain must have escaped his Shadow; for their laughter and the laughter of Orcs are as different as is the light of Aman from the darkness of Angband.” But some thought, nonetheless, that there had been a remote kinship, which accounted for their special enmity. Orcs and Drûgs each regarded the other as renegades.

(Christopher Tolkien goes on to note that “this was only one of several diverse speculations on the origin of the Orcs.”)

* * *

I promised last time to talk about the idea of a fallen world with regard to humans in Middle-earth. This was prompted by a chance association while thinking of Denethor [*], which reminded me that I needed to go back to The Silmarillion and see how compatible it was with a Christian Fall. I checked “On Men,” chapter 12, and it theoretically could be consistent, because it provides basically no detail about the very first humans—perhaps the whole tree-apple-snake-knowledge-loss of immortality thing happened off-page and then they agreed never to speak of it again. But it doesn’t feel like it: “the children of Men spread and wandered, and their joy was the joy of the morning before the dew is dry, when every leaf is green.”

[*] Footnoted because a tangent: some time ago, in a conversation about dispiriting matters, a Christian friend said something like, “At times like these, it’s a comfort to think that we live in a fallen world.” Which was intended, and taken, as black humor, but stuck with me because I’m not Christian (or religious at all) and the idea of a fallen world just doesn’t resonate with me. Denethor, of course, finds it decidedly not a comfort to think that he lives in a world that’s not only fallen but keeps falling, and here we are.

What we get is subgroups making choices, on more or less information, and living with the consequences. (It reminds me of Diane Duane’s Young Wizards series, where each sentient species makes a choice to accept or reject entropy, thus determining their lifespan.) The Númenóreans existed because their ancestors chose to align themselves with the Noldor, and then were destroyed because they chose to listen to Sauron, except the remnant that didn’t. Of course this also isn’t inconsistent with a Christian Fall, because of that whole free will thing, but I sometimes get the impression that the group choices have the potential to be mini-Falls, what with entire societies apparently permanently gone to the dark side.

And that led me to the Drúedain, to see what, as Wild Men, their place in this is. To the extent that innocence gets associated with lack of knowledge or sophistication, and given their hatred of Orcs and their general position as remnants of an older, more nature-focused time, they might be read as unfallen. But on the other hand, they once lived with Elves and Númenóreans, and they made at least a road and statues that endured (at Dunharrow), so they seem to be diminished from what they once were. And while they are clearly positioned as sympathetic—trustworthy, skilled, intelligent, worthy of respect—I can’t imagine anyone reading LotR and thinking that they are the model to which we should aspire. Consider also the marked contrast with Tom Bombadil, that other innocent character who is close to nature and will help travelers but stays within his own borders. (In the first attempt at this re-read, Jo Walton and other people had some very interesting things to say about Bombadil as a thematic unfallen Adam.) I’m not really sure what to make of all this from an in-text perspective, frankly, but I think I’m going to try and see it as “you don’t have to have stone buildings and bright swords to be awesome” and leave it at that.

* * *

Wow, for a short chapter I sure blathered a lot. I have only three quick comments left:

Elfhelm tacitly approves of Merry’s presence. Does he know who Dernhelm is as well? I can’t decide.

Merry thinks of Pippin and “wishe(s) he was a tall Rider like Éomer and could blow a horn or something and go galloping to his rescue.” (Underline added for emphasis.) Nice.

I didn’t quote all of the last paragraph of the chapter in the summary because it was long, but look at the opening sentences:

Suddenly the king cried to Snowmane and the horse sprang away. Behind him his banner blew in the wind, white horse upon a field of green, but he outpaced it. After him thundered the knights of his house, but he was ever before them. Éomer rode there, the white horsetail on his helm floating in his speed, and the front of the first éored roared like a breaker foaming to the shore, but Théoden could not be overtaken.

(Underlines added for emphasis.) Isn’t that a great way to convey momentum?

Okay, big doings next time; see you then.

« Return of the King V.4 | Index<!– | Return of the King V.6 »–>

Kate Nepveu was born in South Korea and grew up in New England. She now lives in upstate New York where she is practicing law, raising a family, and (in her copious free time) writing at her LiveJournal and booklog.