Welcome back to the Lovecraft reread, in which two modern Mythos writers get girl cooties all over old Howard’s original stories.

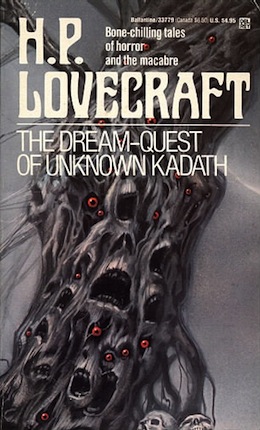

Today we’re looking at the first half of “The Dream-Quest of Unknown Kadath,” written in 1926 and 1927, and published posthumously in 1943 by Arkham House. You can read it here—there’s no great stopping point, but we’re pausing for today at “One starlight evening when the Pharos shone splendid over the harbour the longed-for ship put in.” Spoilers ahead.

“It was dark when the galley passed betwixt the Basalt Pillars of the West and the sound of the ultimate cataract swelled portentous from ahead. And the spray of that cataract rose to obscure the stars, and the deck grew damp, and the vessel reeled in the surging current of the brink. Then with a queer whistle and plunge the leap was taken, and Carter felt the terrors of nightmare as earth fell away and the great boat shot silent and comet-like into planetary space.”

Three times Randolph Carter dreamt of a fabulous sunset city, and three times he woke before descending from his terrace vantage to explore its streets. Almost vanished memory haunts Carter—in some incarnation, the place must have held supreme meaning for him.

He prays for access to the gods of Earth’s dreamlands, but they make no answer. Sick with longing, he decides to seek Kadath in the cold waste, abode of the gods, there to petition in person.

Carter descends the seventy steps of light slumber to the cavern of Nasht and Kaman-Thah. The priests tell him no one knows where Kadath lies, not even whether it’s in Earth’s dreamlands. If it belongs to another world, would Carter dare the black gulfs from which only one human has returned sane? For beyond the ordered universe Azathoth reigns, surrounded by the mindless Other Gods whose soul and messenger is the crawling chaos Nyarlathotep.

Despite their warning, Carter descends the seven hundred steps into deeper slumber. He passes through the Enchanted Wood, peopled by small, brown, slippery Zoogs. They can’t tell where Kadath lies. With three curious Zoogs following, Carter traces the river Skai toUlthar, where cats greet him as their long-time ally and he consults with the patriarch Atal. Atal cautions against approaching Earth’s gods; not only are they capricious, but they have the Other Gods’ protection, as Atal learned when his master Barzai was drawn into the sky for god-hunting atop Hatheg-Kla.

But Carter intoxicates Atal with Zoogian moon-wine, and the old man speaks of Mount Ngranek on Oriab Isle in the Southern Sea, upon which the gods have carved their own likeness. Knowing what the gods look like would let Carter seek similarly featured humans—children the gods begot in human guise. Where these people are common, he reasons, Kadath must be near.

Outside Carter finds that cats have devoured his Zoog tails, who’d looked with evil intent on a black kitten. Next day he heads to Dylath-Leen, port town of basalt towers. A ship from Oriab is due shortly. While Carter waits, black galleons arrive from parts unknown. Merchants with oddly humped turbans debark to sell rubies for gold and slaves. The prodigiously powerful oarsmen are never seen. One merchant drugs Carter, and he wakes aboard a black galleon bound for the Basalt Pillars of the West! Passing through them, the galleon shoots into outer space and toward the moon, while the amorphous larvae of the Other Gods caper around it.

The galleon lands on the dark side of the moon, and malodorous lunar toads swarm from the hold. A squadron of toads and their horned (hump-turbaned!) slaves bear Carter toward a hill-top cave, where Nyarlathotep waits. Luckily old folk are right about how cats leap to the moon at night, for Carter hears one yowling and calls for help. An army of cats rescues him, then bears him back to Dreamlands-Earth.

Carter’s in time to board the ship from Oriab. On that vast isle, he learns no living man has seen the carved face on Ngranek, for Ngranek’s a hard mountain, and night-gauntsmay lurk in its caverns. Carter’s undeterred, even after losing his zebra mount to a blood-drinking mystery in the ruins on Lake Yath. ClimbingNgranek is indeed difficult, but sunset finds him near the summit, the carven face of a god glowering down. He recognizes its features—narrow eyes, long-lobed ears, thin nose and pointed chin—as similar to sailors from Inquanok, a twilight northern realm. He’s seen them in Celephais, where they trade onyx, and isn’t the castle of the gods said to be made of onyx?

To Celephais Carter must go. Alas, as night falls on Ngranek, night-gaunts emerge from a cave to carry him down to the Dreamlands’ underworld! The faceless, tickling horrors leave him in the lightless vale of Pnoth, where the Dholes burrow unseen. Unknown depths of bone stretch in all directions, for the ghouls toss their refuse into the vale from a crag high above. Good news! Carter was friends with Richard Upton Pickman in waking life, and Pickman introduced him to the ghouls and taught him their language. He gives a ghoulish meep, which is answered by a rope ladder that arrives just as a Dhole comes to nuzzle him.

Carter climbs to the ghouls’ underworld domain, where he meets Pickman turned ghoul. His old friend lends Carter three ghouls who guide him to the Gug city, where a vast tower marked with the sign of Koth rises to the upper Dreamlands—in fact, to the very Wood where the quest began. Encounters with loathsome hopping ghasts and gigantic Gugs aside, Carter reaches the Wood unscathed. There he overhears a counsel of the Zoogs, who plan to avenge themselves on the cats of Ulthar for the loss of their three spies. Carter, however, calls in a cat army to nip their nefarious plan in the bud. The cats escort Carter out of the Wood and see him off to Celephais.

Carter follows the river Oukranos to that marvelous city on the Cerenerian Seawhere he’s seen men with divine features. Hehears that these men of Inquanok live in a cold land near the evil plateau of Leng, but that may just be fearful rumor. While he waits for the next ship from Inquanok, Carter ignores yet another priest who warns him to give up his quest and visits his old friend Kuranes, king of Ooth-Nargai and the cloud-city Serannian and that only human to have returned from beyond the stars still sane.

But Kuranes is neither in Celephais nor Serannion, because he’s created a faux-Cornwall of his waking youth and retired there, weary of Dreamland splendors. Kuranes, too, warns Carter against the sunset city. It can’t hold for Carter that link to memory and emotion that his waking home does. Finding it, he’ll too soon long for New England, as Kuranes longs for the old one.

Carter disagrees and returns to Celephais, determined as ever to beard the gods of Earth upon Kadath.

What’s Cyclopean: Round towers and steps in the land of the Gugs. But the words of the day are “fungous” and “wholesome”—clearly intended as dramatic opposites. Cats, it seems, are particularly wholesome.

The Degenerate Dutch: One gets the impression that the amorphous frogs are bad guys, not because they’re slavers, but because they enslave Carter in particular.

Mythos Making: Randolph Carter turns out to be old friends with Richard Upton Pickman—and doesn’t “drop him” even in his now-full-grown ghoul form. In the background—so far—lurk Nyarlathotep and the Other Gods who protect Earth’s Great Ones. Plus we finally get to meet night-gaunts. Hope you’re not ticklish.

Libronomicon: Ulthar, which doesn’t really seem the place for it, holds copies of the Pnakotic Manuscripts and the Seven Cryptical Books ofHsan.

Madness Takes Its Toll: Cross the gulf between the Dreamlands of different stars, and risk your sanity.

Ruthanna’s Commentary

I didn’t find our first Dreamlands story, “The Doom That Came to Sarnath,” terribly promising—I thought it was overwrought, overly derivative prose and an overwrought, overly derivative story. But seven years later, Lovecraft’s made the setting his own. “The Cats of Ulthar” has given it an unfallen city (or at least town) and fierce protector. “The Other Gods” has drawn the first big connection with the central Mythos, and “Strange High House in the Mist” has confirmed that the two bleed into each other. The Dreamlands are the nice neighborhood, but not too nice, and they make up for it with a dream logic in which anything can happen. And in a Lovecraft story, “anything” is a pretty broad brush.

We start with a visit to the Zoogs. (I love that Howard never stops and asks whether a name sounds too silly to be effective, with the result that his names are more alien than those produced by 99% of other SF authors—most of whom can’t even resist ending all female names with “a.” The red-footed wamps are another great example.) From Zoogs we’re on to “wholesome” Ulthar, a good shire-ish starting point for any quest. But then we go to the moon, captured by amorphous tentacled moon frogs, get rescued by cats, leap back to earth, meet ghouls and Gugs, see immense carven gods, get tickled by night-gaunts. That’s scarier than it sounds, and the gaunts have the perfect logic of a childhood nightmare, as indeed they apparently were.

Dream-Quest is also the climax of Randolph Carter’s story (ignoring “Through the Gate of the Silver Key,” as one should). He’s recovered from his PTSD (we’ll see just how recovered later), and “old in the land of dreams.” Two lifetimes old, at least. He’s confident enough to ignore everyone’s warnings—people constantly urge him not to go in the direction of the plot, and he stubbornly heads plotward—and skilled enough to survive those decisions. A far cry from the Carter who sat nervously in a cemetery while someone else went down into the earth and reported on the wonders and terrors below. The mature Carter descends into the underworld, returns with wisdom and companions, and goes back as needed. It doesn’t hurt that he speaks both Cat and Ghoul fluently.

I rather like that Lovecraft himself plays Lovecraftian monster apologist here. The ghouls still aren’t fun to be around—given their diet, one suspects that ghoul breath stinks like a komodo dragon. But they have language, are generous to their friends and brave in the face of danger, and seem like all-around decent people. Plus they confirm that the unlikely underground caverns and passages—you know, the ones everyone complains about in comments—go down into the Dreamlands. The ghouls toss detritus there from their Boston cemeteries (and from everywhere else).

And what the heck are the Dreamlands, anyway? They’re home to real people who have their own lives and sometimes their own stories. They have enough internal logic that they can’t be the setting for everyone’s dreams. You can still sleep and dream once there. Gods move back and forth freely; so do ghouls and gaunts. They have equivalents on other worlds. They seem to be a place you can reach through a different kind of dream—or through particular trapdoors and impossible cliffs in the “waking world”. Homeland of the gods? Convenient long-term archetype storage? Just another layer of the cosmos, that happens to hold particular appeal for some of Earth’s more intrepid souls?

Unlike the Carter of “Gates,” this Carter isn’t interested in learning the secrets of the cosmos. He just wants his sunset city. On the borderlands of the Mythos, that’s a considerably more sensible choice.

Anne’s Commentary

When I descend the seventy steps into the Cavern of Flame, Nasht and Kaman-Thah always direct me to my own New England dream-world, which is more urban than Lovecraft’s, full of abandoned mills whose labyrinthine basements descend forever. Also beach houses from whose windows I watch a hundred-foot tsunami roll straight toward me. Pretty cool, but there go the waterfront property values.

One night I’d love to venture into the Dreamlands instead. So what if GPS doesn’t work there? Just slink into a dockside tavern and question the shady characters at the bar — one will eventually drop a clue about your destination. Priests can also be helpful, if very old and drunk and named Atal.

UntilNasht and Kaman-Thah cooperate, I’ll have to be content with rereading Randolph Carter’s adventures, and I’ve reread them many times. Dream-Quest is one of my most reliable comfort books — crack the cover, and I fall into fictive trance. Any Austen novel does the same for me, so there must be a deep connection between Howard and Jane. It probably threads a crooked path through the vale of Pnoth, so let’s not go there now. The Dholes are hungry this time of day.

Instead let’s talk about description, the interplay of the highly specific and the evocatively vague that marks this novel. There are things Lovecraft specifies so consistently that the authorial act seems almost compulsive. Architecture, for example. Ulthar is Olde-Englishy (or Puritan-New-Englishy) with its peaked roofs, narrow cobbled streets, overhanging upper stories and chimney pots.Dylath-Leen has thin, angular towers of basalt, dark and uninviting. The moon-town has thick gray towers without windows (no windows is never a good sign.) Baharna gets a little short-changed apart from its porphyry wharves. The ghoulish underworld is drab, just boulders and burrows, but the Gugs have a subterrane metropolis of rounded monoliths culminating in the soaring tower of Koth. Both Kiran and Thran get long paragraphs, the former for its jasper terraces and temple, the latter for its thousand gilded spires. Hlanith, whose men are most like men of the waking world, is mere granite and oak, but Celephais has marble walls and glittering minarets, bronze gates and onyx pavements, all pristine, because time has no power there.

Very important, what a place is made of, and how it’s made, and whether there are gardens or only fungous mould. The setting mirrors the character of its makers and keepers.

Lovecraft often minutely describes the creatures of his own imagination, especially when their features are as striking as the Gug’s(two massive forearms per massive arm, and that vertical mouth!) Ghasts and night-gaunts and moon beasts also get detail, while other originals get a briefer physical description but a fuller behavioral one. We’re told the Zoogs are small and brown, not much to go on, but their nature’s revealed in their elusiveness, their fluttering speech, their curiosity and their “slight taste for meat, either physical or spiritual.” Then there are the unseen Dholes. How to capture their awfulness? Lovecraft does it with masterful specifics, their rustling beneath the deep mulch of bones, the way they approach “thoughtfully,” their touch. That touch! “A great slippery length which grew alternately convex and concave with wriggling.” Nasty. Effective.

But the greatest strength of Dream-Quest may lie in Lovecraft’s hints, the stories he doesn’t pull all the way out of the wide narrative river that is the Dreamlands, with all its Mythos tributaries. These stories remain glimpses beneath the purling surface, like the scale-flashes which predatory fish in the river Oukranos use to lure birds. I think of the curious cats of Saturn, foes of Earth’s cats. Of whatever drains zebras of their blood and leaves webbed footprints. Of the sunken city over which Carter sails enroute to Oriab. Of the red-footed wamp, about which we learn only that it’s the ghoul-analog of the upper Dreamlands, spawned in dead cities. Of the lumberingbuopoths. Of the god who sings in Kiran’s jasper temple. Of the perfumed jungles of Kled with their unexplored ivory palaces. Even of hill fires to the east of Carter’s Celephais-bound galleon, which one better not look at too much, it being highly uncertain who or what lit them.

Who! What! Why and where and how? Wisely, Lovecraft leaves those dark matters to us dreamer-readers to ponder, a trove of possibilities.

Join us next week as the Dreamquest continues! Who are the strange men with the faces of gods? What secrets lurk beyond the forbidden plateau of Leng? Why does the crawling chaos, Nyarlathotep, keep getting in the way of our hero’s quest?

Ruthanna Emrys’s neo-Lovecraftian novelette “The Litany of Earth” is available on Tor.com, along with the more recent but distinctly non-Lovecraftian “Seven Commentaries on an Imperfect Land.” Her work has also appeared at Strange Horizons and Analog. She can frequently be found online on Twitter and Livejournal. She lives in a large, chaotic household—mostly mammalian—outside Washington DC.

Anne M. Pillsworth’s short story “Geldman’s Pharmacy” received honorable mention in The Year’s Best Fantasy and Horror, Thirteenth Annual Collection. “The Madonna of the Abattoir” is published on Tor.com, and her first novel, Summoned, is available from Tor Teen. She currently lives in a Victorian trolley car suburb of Providence, Rhode Island.