A lot of people know the science fiction legend Harry Harrison without knowing they know him. For example, Charlton Heston fans. In 1973, Heston starred in Soylent Green, a movie about a murder investigation set in a futuristic New York City, where overpopulation and pollution have ravaged the world’s food supplies. While the rich are largely unaffected, the masses are forced to eat processed wafers of several varieties: Soylent Red, Soylent Yellow, and the titular Soylent Green, which—spoiler alert—turns out to be recycled human remains (thus, the movie’s haunting and very famous final line: “Soylent Green . . . is . . . people!”). It is a surprisingly enduring movie, likely due to its all-star cast, which also included Joseph Cotten, Chuck Connors (of TV’s The Rifleman), and, in the last of his 101 (!) film roles, Edward G. Robinson. The movie won a Nebula Award for Best Film Script and a Saturn Award for Best Science Fiction Film.

Where does Harry Harrison come in? Soylent Green is based on his novel Make Room! Make Room!, which is more didactic, doesn’t involve an evil corporation, and whose ending lacks the movie’s gruesome twist. The idea for the book originated, in Harrison’s words, from an Indian gentleman he met in 1946 who told him about the dangers of overpopulation and then said, “Want to make a lot of money, Harry? You have to import rubber contraceptives to India.”

The literary world—and, for all I know, the condom industry—should be grateful that Harrison didn’t follow this advice.

Born in 1925 in Stamford, Connecticut, Harry Harrison is not quite a household name. He never won a major literary award, and to date only one of his books—the aforementioned Make Room! Make Room!—has been adapted for TV or film. Yet he was a dogged and versatile writer and artist. After serving in the U.S. Army Air Forces during World War II, Harrison worked as an illustrator for various science fiction magazines and comic books, most notably the EC Comics titles Weird Fantasy and Weird Science. Later, he was the main scribe of the Flash Gordon comic strip and the ghostwriter of several tales featuring Leslie Charteris’s character Simon Templar, a.k.a. The Saint. A member of New York’s so-called Hydra Club, he counted among his friends such luminaries as Alfred Bester, James Blish, Anthony Boucher, Avram Davidson, Lester del Rey (who would marry Harrison’s first wife, Evelyn, after the couple’s 1951 divorce), Judith Merril, Frederik Pohl, L. Sprague de Camp, Theodore Sturgeon, and Isaac Asimov. He edited magazines and anthologies, including, with the British writer Brian Aldiss, the first nine volumes of The Year’s Best Science Fiction anthology series.

And, of course, he wrote books. Sixty or so in all.

Science fiction was still an emerging genre when Harrison joined it. Though the 19th century had given us such writers as Jules Verne, H.G. Wells, and Mary Shelley (her Frankenstein is widely considered the world’s first sci-fi novel), the genre got its real start in the late 1930s, a period often thought of as the Golden Age but which Robert Silverberg calls “a false dawn.” For him, the real gold came in the 1950s, a decade that set off “a grand rush of creativity, a torrent of new writers bringing new themes and fresh techniques that laid the foundation for the work of the four decades that followed.” The year 1950 alone saw the publication of Asimov’s Pebble in the Sky, Merril’s Shadow on the Hearth, Robert A. Heinlein’s Farmer in the Sky, and Theodore Sturgeon’s The Dreaming Jewels. That September, The New York Times reported that “more science fiction novels and anthologies will be published this fall alone than in any previous full year.”

Later came Arthur C. Clarke’s Childhood’s End, Ward Moore’s Bring the Jubilee, and of course, Ray Bradbury’s Fahrenheit 451. I tend to think of this period as characterized by pure entertainment—linear narratives, clear heroes and villains, space opera, high technology. And for a while, it just kept growing. By 1953 there were forty or fifty times the number of outlets for science fiction than had existed five years earlier, according to Barry Malzberg.

By the end of the decade, however, the market had cooled. Malzberg called this period “an unhappy, airless time.” Good work was still being done—Heinlein’s Starship Troopers, for instance (1959)—but in general, things didn’t get popping again until the rise of the so-called New Wave writers of the mid-1960s: Philip K. Dick, Harlan Ellison, Kurt Vonnegut, Ursula K. Le Guin, Octavia Butler, and J.G. Ballard. “Influenced by modernist prose and poetry,” write Iain McIntyre and Andrew Nette, “[t]he New Wave still had its astronauts and interstellar explorers, but now they could be found psychologically crumbling under the physical and mental pressure of space flight and the directives of the oppressive military bureaucratic apparatus behind it.”

Amid this upheaval, Harrison published his first story, “Rock Diver,” about land prospectors who travel to the Earth’s core. He was a regular in sci-fi magazines for the next few years until the publication of his first novel, Deathworld, in 1960. You can see how it straddles the decades, creating what one reviewer calls “a Golden Age conceit imbued with New Age ideals.” Jason dinAlt is a gambler with psychic abilities who travels to a planet called Pyrras, or Deathworld. The sobriquet comes from the fact that everything on the planet—animals, plants, the atmosphere—is deadly to humans. The Pyrrans are divided and have no hope of survival unless Jason can unite them. It is a tale of ecological disaster that can only be ameliorated through the reconciliation of competing social views. (Sound familiar?)

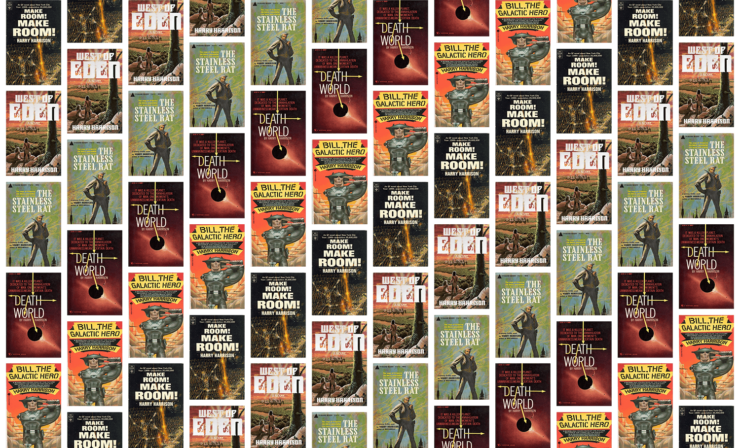

Though it spawned two sequels, Deathworld isn’t always a fave among Harrison fans (you can judge for yourself: the whole thing is available at Project Gutenberg), maybe because it takes itself too seriously. His next novel, The Stainless Steel Rat (1961), is the perfect antistrophe: An expansion of a story that appeared in the August 1957 issue of Astounding Science Fiction, the book was Harrison’s biggest success, inspiring eleven sequels, a gamebook, a board game, a Commodore 64 video game, and a comic book series.

The story centers on James Bolivar diGriz, a.k.a. Slippery Jim or the Stainless Steel Rat, a thief and con man who (not unlike the star of Harrison’s old ghostwriting assignment, Simon Templar) steals only from those who can afford it—i.e., companies with excellent insurance policies. He runs afoul of Harold Inskipp, a crook-turned-cop who cajoles diGriz into joining his collective of crooks-turned-cops called the Special Corps. On his first mission, diGriz matches wits with the beautiful but murderous Angelina, who, like diGriz, ends up joining the Corps—and falling in love with him to boot.

Unlike the tortured environmentalism of Deathworld and the Malthusian crisis of Make Room! Make Room!, Harrison’s Rat series is an escapist delight: robots, warships, faster-than-light space travel, and a loosely-organized system of interstellar government. Basically, it’s Star Trek sans Gene Roddenberry. The books aren’t laugh-out-loud funny, yet they move with a briskness and buoyancy that will make you smile, such as in this inner monologue by diGriz:

Bit by bit a pattern started to emerge. A delicate webwork of forgery, bribery, chicanery and falsehood. It could only have been conceived by a mind as brilliantly crooked as my own. I chewed my lip with jealousy.

Slippery Jim is an antihero in the vein of Captain Jack Sparrow—entertaining, droll, a cad with a moral compass (he steals everything, but abhors killing). Also, he speaks Esperanto, the conlang created in 1887 by L.L. Zamenhof. The language was dear to Harrison, who learned it in the Army out of boredom and later stated that he could “write and speak it with an automatic ease I have never been able to capture in any language other than my native English.” He was the honorary president of the Esperanto Association of Ireland and also held memberships in other organizations such as Esperanto-USA and the Universal Esperanto Association.

And there were other triumphs, such as Bill, the Galactic Hero (1965), which filmmaker Alex Cox described as “the great, transgressive riposte to Starship Troopers” and Terry Pratchett, who knew a thing or two about comedy, called “the funniest science fiction novel ever written.” (The six sequels were less well-received.) His Eden trilogy (1984-1988), an alternate history in which dinosaurs survive extinction to become superintelligent enemies of mankind, has been called “by a considerable margin Harrison’s best work.” He was inducted into the Science Fiction Hall of Fame in 2004 and received a Science Fiction & Fantasy Writers Association Grand Master Award in 2009; yet he was never at ease with his success in the field, criticizing the current state of science fiction as “rubbish” and characterizing it as “[i]ncompetent, unlettered, unskilled writers sell[ing] to unexacting editors. All of this is going completely unnoticed by an incompetent readership.”

Let me indulge my incompetence by saying this: the world needs a big-budget movie or TV adaptation of Harry Harrison’s fiction. Hollywood’s neglect when it comes to his work is as egregious as their apparent disregard for the great Robert Asprin. Soylent Green, for example, is fifty years old—it could use a refresh. The aforementioned Alex Cox once directed a student production of Bill, the Galactic Hero (available on YouTube), and it isn’t bad. It just, you know, looks like a film that cost roughly the same as my first car. Then there’s The Stainless Steel Rat, which, with the comics and games, is already a franchise of sorts. Other than Make Room! Make Room!, it has come the closest in Harrison’s oeuvre to actually being adapted for a mainstream audience. In 2000, the rights were acquired by Dutch filmmaker Jan de Bont, a cinematographer (Die Hard, The Hunt for Red October) turned director of blockbusters like Speed and Twister.

Twenty-three years have passed since then, and Jan de Bont is now retired. It’s time for somebody else to make this movie. I know, I know—getting started is the hard part. Here, I’ll help. Who should play Jim diGriz? That’s easy: Bradley Cooper. For the femme fatale Angela, I see Lily Rabe or Sidney Sweeney. Christoph Waltz has the villainous panache to pull off Harold Inskipp. Style-wise, the film should be a mix of the original Star Trek’s swashbuckling and Next Generation’s postmodernism, with a little Lower Decks burlesque thrown in…

But let’s hear from you: Who would be your casting choices for The Stainless Steel Rat, and what director should finally bring it to the big screen? Or would you rather see an adaptation of a different Harry Harrison work ? Let me know in the comments below…

Anthony Aycock is a librarian and freelance writer who has published in Slate, the Washington Post, Medium, the Missouri Review, the Gettysburg Review, and other venues. See more of his work at his website.