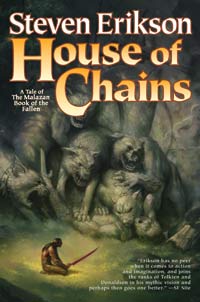

Welcome to the Malazan Re-read of the Fallen! Every post will start off with a summary of events, followed by reaction and commentary by your hosts Bill and Amanda (with Amanda, new to the series, going first), and finally comments from Tor.com readers. In this article, we’ll cover Chapter Two of House of Chains by Steven Erikson (HoC).

A fair warning before we get started: We’ll be discussing both novel and whole-series themes, narrative arcs that run across the entire series, and foreshadowing.

Note: The summary of events will be free of major spoilers and we’re going to try keeping the reader comments the same. A spoiler thread has been set up for outright Malazan spoiler discussion.

Chapter Two

SCENE 1

The Rathyd warriors have pulled back the hunt, planning on attacking the three when they return back through their lands. They decide to avoid the other Rathyd villages until the very last one, so as to draw hunters into the Sunyd lands and spark a conflict. They continue on the ride, with Karsa showing surprising concern for a dog wounded in the last fight (now three-legged) and the lead pack dog he had dominated and then named Gnaw. They find a cave along what Phalk had called Bone Pass. Inside strange glyphs cover the back wall—Teblor language but strangely “ornate.” Karsa begins to read the inscription: I led the families that survived . . . Through the [ice] . . . We were so few. Our blood was cloudy and would grow cloudier still. I saw the need to shatter what remained. For the T’lan Imass were still close . . . and inclined to continue their indiscriminate slaughter . . . I fashioned new families and . . . proclaimed the Laws of Isolation, as given us by Icarium whom we had once sheltered and whose heart grew vast with grief upon seeing what had become of us.” When Delum says the words disturb him, Karsa calls them the mad ravings of an elder. He continues to read: “To survive, we must forget. So Icarium told us . . . We must forget our history and seek only our most ancient of legends . . . when we lived simply. In the forests. Hunting . . .When our laws were those of the raider . . . murders and rapes. We must return to those terrible times. To isolate our streams of blood, to weave new, smaller nets of kinship. New threads must be born of rape, for only with violence would they remain rare occurrences, and random.” When he recognizes the names of the clans listed, Karsa refuses to read farther and commands that they sleep outside the cave.

SCENE 2

Two nights later, they are at the edge of Sunyd lands, but they haven’t been able to lure Rathyd warriors with them and in fact found the last few villages abandoned. It appears the Sunyd lands are also abandoned, the people flown, but not from Karsa and his friends since the running away seemed to take place long ago. They plan to attack Silver Lake the next day. As they camp for the night, they discuss the cave writing and Bairoth says he believes there is truth amid the ravings and that the language is from a time when the Teblor language was more sophisticated. Karsa says the idea that the Teblor are a “fallen people” is nothing new, that there are tales of past glory. But the other two argue those tales are tales “of instruction, a code of behavior, the proper way of being a Teblor,” and that the cave writings explained why. Delum points out all the children given to the Faces in the Rock due to birth defects caused by inbreeding. Karsa says they are missing the point—if they were defeated, had fallen the job is to rise once more. Bairoth wonders if the Sunyd lands are empty because the Teblor have been defeated yet again. When Karsa argues they can change that, Bairoth says he prays that Karsa’s mind “ever remains free of doubt.” When Karsa takes that as Bairoth saying Karsa is as weak as his father, Bairoth tells him Synyg is not weak, and if anything should be doubted it should be Pahlk’s stories. He sees potential in Karsa to become his father’s son and says he lied when he said he prayed Karsa never faced doubt, that in fact he prays that doubt “tempers [him] with wisdom. Those heroes in our legends . . . they were terrible, they were monsters, for they were strangers to uncertainty.” Karsa challenges Bairoth, but Bairoth refuses to fight and when Karsa demands an apology, Bairoth does so.

SCENE 3

In the village they realize that lowlanders had attacked the Sunyd village. Karsa says their mission now changes from a raid by Uryd to vengeance as Teblor. As they move toward Silver Lake, they come across a huge flat slab of stone with a blue-green hand with a strange number of joints sticking out from under it. It moves when Karsa nears it. He calls it a “demon pinned for eternity beneath that stone,” and Delum names it Forkassal, from their legends—the One Who Sought Peace. They rehash the old tales of the Spirit Wars, invasions involving foreign gods and demons who battled in the mountains until only one group remained. Icarium was in those stories and Delum wonders if the T’lan Imass mentioned in the cave were the victors in that war, and it was that war that shattered the Teblor. Bairoth says they should free the demon. He recalls how the legends say the Forkassal tried to make peace between the opposed forces and it was destroyed. Then Icarium tried, but came too late, but the victors didn’t even try to fight him, knowing how futile it would be. He points out that the cave inscription said it had been Icarium who gave the Teblor the Laws that let them survive and that the Imass would have pinned him under a stone as well if they could have. Delum worries the demon may have gone mad, and that the Imass only pinned it because they could not kill it, meaning it could easily handle the three Teblor. They lift the slab and free the creature. When Bairoth goes to help her rise, Karsa tells him she has known such pressure from the slab she will not wish to to be touched most likely, an insight which surprises Bairoth. Delum goes to get water and Karsa notices that when she looks up, her smile “mocks her own sorry condition. This, her first emotion upon being freed. Embarrassment, yet finding the humour within it.” This response makes him vow that the T’lan Imass who imprisoned her (or their descendants) shall be his enemy. Delum returns but before he can offer the water, she suddenly attacks, knocking Karsa down and throwing Delum hard to the ground. She stands above Karsa and tells him “They will not leave you, will they? These once enemies of mine. It seems shattering their bones was not enough . . . Your kind deserves better . . . I must needs wait . . . and see what becomes of you.” When Bairoth calls her Forkassal, she tells him “you have fallen far , to so twist the name of my kind, not to mention your own. I am Forkrul Assail . . . I am named Calm.” When he wonders how she could attack them after they freed her, she says “Icarium and those damned T’lan Imass will not be pleased that you undid their work . . . but I do know gratitude and so I give you this. The one named Karsa has been chosen. If I was to tell you even the little that I sense of his ultimate purpose, you would seek to kill him. But I tell you there would be no value in that, for the ones using him will simply select another . . . Watch this friend of yours. Guard him. There will come a time when he stands poised to change the world. And when that time comes, I shall be there. For I bring peace. When that moment arrives, cease guarding him. Step back, as you have done now.” She leaves. Delum’s skull is cracked and is leaking brain fluid. Bairoth regrets his advice to free her and is shamed he did not try to fight. Karsa tells him at least one of them is healthy. They bandage Delum though they know he will not regain his thoughts. They return to camp.

SCENE 4

Delum moves happily among the dogs, but seems not to even see Karsa or Bairoth. Bairoth is clearly feeling guilty, but Karsa “had little understanding of such feelings, this need to self-inflict some sort of punishment. The error had belonged to Delum . . . The Faces in the Rock held no pity for foolish warriors, so why should Karsa Orlong? Bairoth Gild was indulging himself, making regret and pity and castigation into sweet nectars.” When Bairoth appears with game, Delum acts like a dog in taking a piece and baring his teeth at the “other” dogs. Bairoth says Delum would have been better killed and when Karsa tells Bairoth to kill him then, Bairoth says he will no longer follow Karsa. Karsa calls him weak and foolish and says if he wishes to survive, he needs to follow Karsa. Bairoth tells him how Bairoth and Dayliss had been lovers for a long time and had laughed at Karsa’s strutting. He believes only Karsa will return to their village and when he does so he will wed Dayliss, but, he tells Karsa, in that case it will be Karsa who followed, not Bairoth. When Karsa says he will instead denounce Dayliss for sleeping with a man not her husband and will claim her as his slave, Bairoth attacks him, but before he can do much damage the dogs attack him. Karsa calls them off. They’re interrupted by torchlight coming closer. They see lowlanders come to where the Forkrul Assail had been imprisoned. Karsa attacks and kills the soldiers then, to the shock of the four mages in the group, he walks through their sorcerous fire attack and kills them as well, though one guard manages to escape. Bairoth agrees to follow Karsa in this war.

SCENE 5

They trail the escaped guard and come across two dogs he had killed with crossbow bolts. Karsa decides to go by him and beat him to Silver Lake. They move on and come to a notch in the mountains with water pouring through cracks in the rock. Karsa realizes the scene makes no natural sense and Bairoth agrees, saying the notch wasn’t carved by the river but looks as if some god had “broken a mountain in half . . . It has the look of having been cut by a giant axe.” They find a staircase of bones leading down, confirming at least part of Pahlk’s tale. The stairs were made by “an army had been slain, their bones then laid out, intricately fashioned into these grim steps” and based on the length and depth, Bairoth estimates tens of tens of thousands had been killed. They descend and make camp in a place which according to Pahlk’s description should be only a few days from Silver Lake.

SCENE 6

They grow very close and make camp for the night. Bairoth wonders what the lowlanders had been doing at Calm’s imprisonment site and Karsa says maybe they were going to free her. Bairoth says he thinks they came to worship, that maybe Calm was their god, and maybe her soul could be drawn out like the Faces in the Rock. Karsa tells him “that demon was not a god. It was a prisoner of the stone. The Faces in the Rock are true gods. There is no comparison.” Bairoth replies he wasn’t making one, pointing out “The lowlanders are foolish creatures, whilst the Teblor are not. The lowlanders are children and are susceptible to self-deception.” When Karsa wonders why Bairoth is harping on the issue, Bairoth says “I believe the bones of Bone Pass belong to the people who imprisoned the demon . . . it may be the lowlanders are kin to that ancient people.” Karsa says he doesn’t care; tomorrow they will slay the lowlanders.

SCENE 7

In the morning, Bairoth paints Delum’s face in the manner that warriors do who know they ride to their own deaths, usually aged warriors. Karsa complains Bairoth is dishonoring all Teblor who have worn the battle-mask, but Bairoth answers “Do I? Those warriors grown old, setting out for a final fight—there is nothign of glory in their deed . . . in their battle-mask . . . They come to the ends of their lives and have found that those lives were without meaning. It is that knowledge that drives them . . . to seek a quick death.” He asks Karsa what he sees in Delum’s eyes and when Karsa says “nothing,” Bairoth says “Delum sees the same, Warleader. He stares at nothing. Unlike you, however, he does not turn away from it. Instead, he sees with complete comprehension. Sees and is terrified . . . We can offer Delum no comfort . . . he will die this day Karsa Orlong, and perhaps that will be comfort enough.” As they prepare, Karsa goes over the description of the farmstead Pahlk gave him. Bairoth wonders how many lowlander generations have passed and Karsa dismisses the question with “enough.” They charge around a pinnacle of rock and where they had expected to see a single farm or perhaps a few, stands a walled town with a gate and towers, stone buildings and piers, and a lot more lowlanders than planned on. An alarm bell begins to ring as Karsa and Bairoth charge, killing a few lowlanders on the way to the town. Havok leaps the wall (about the height of a man), separating Karsa from Bairoth momentarily before he rides in through the gate that Karsa breaks down by hand. The two, along with the dogs and even Delum (who attacks like a dog) wreak slaughter throughout the town. As they ride and fight, they come across a pile of “bleached bones, from which poles rose, skulls fixed to their tops. Teblor skulls.” Bairoth’s horse is killed, then Havok is as well, and the two are separated. Karsa sees Delum killed. He kills Delum’s slayer, then rescues a badly wounded Gnaw and leaves him in a barn, before making his way to a raised platform in a warehouse. He jumps down to kill a lowlander, but his impact collapses the floor and falls into the cellar and is impaled above the shoulder blade by a spike of wood (he has already been “festooned with arrows and quarrels). A lowlander (turns out to be the guard who had earlier escaped at Calm’s site) speaks to him and when Karsa names himself and mentions Pahlk, the lowlander asks “the Uryd who visited centuries ago?” Karsa says yes, “to slay scores of children.” But the man says that Pahlk killed nobody, “not at first. He came down from the pass half starved and fevered” and after farmers nursed him back to health, he killed them and fled. The lowlander says they know all about the Uryd from the Sunyd slaves, and that while they haven’t reached Karsa’s tribe yet, they will, and “within a century there will be no more Teblor in . . . Laederon Plateau [save those] branded and in chains.” Karsa is bound and brought up, where he is surrounded by cursing lowlanders. When he smiles at them, the lowlander wonder is Karsa “is the one the priests spoke of. The one who stalked their dreams like Hood’s own Knight?” A new lowlander arrives—Master Silgar—and after speaking to him the lowlander guard says Silgar has “prepared for you a lesson of sorts.” They drag Karsa out to see Bairoth, badly wounded and tied to a spoked wheel. The guard tells Karsa Bairoth refuses to give up any details of the Uryd and Karsa says he will tell them as it won’t matter. The guard draws his sword then and just before he kills Bairoth, Bairoth yells out “Lead me, Warleader.” The guard tells Karsa after he talks Silgar will add him to his slaves. A soldier appears then and the guard tells Karsa it is a Malazan captain, and it was bad luck for Karsa that his attack was while a Malazan company was staying in Silver Lake on their way to Bettrys.

SCENE 8

After Karsa tells them of the Uryd, he is brought to a slave pit in a warehouse and chained to a tree trunk. He concentrates on forcing a remaining arrowhead out of his shoulder. Once he does so, he wonders about Bairoth’s last moments. He didn’t understand why he had refused to speak, as the lowlanders wouldn’t be able to defeat the Uryd no matter what they learned. And he wondered why Bairoth’s last words had sounded like a curse, why Bairoth had abandoned him. He worries his tribe will not follow him when he declares war against the lowlanders but then thinks they will have no choice once the lowlander armies arrive. He finds the arrowhead he forced out of his body and starts using it to chip away at the log where his chains connected. He manages to weaken the shackles somewhat and while he rests, the guard enters to check on him. He tells Karsa Silgar seems to have been right that it will take time to break Karsa’s spirit, but he adds that it will happen eventually. Karsa asks his name and the guard answers he is Damisk, “once a tracker in the Greydog army during the Malazan conquest.” Karsa then asks if it was a conquest, then whose spirit has been broken, and then points out that Damisk ran away in their earlier meeting, and now taunts Karsa only because he is chained. When Damisk leaves, a slave speaks to Karsa and asks if he will succeed at whatever he is attempting with the tree and chains. He says he was part of a group that refused to accept the Malazan conquest and fought from the forests until they were caught. He tells Karsa to spin the log to shorten their chains. He then says it will drag him and his fellows under so they will drown and when Karsa asks if he means for Karsa to kill him, the slave says “More souls to crowd your shadow.” But he then points out by spinning the log he will get water into the shaft and soften things and weaken them more. Karsa spins the log and eventually, to his surprise, the slave appears. He introduces himself as Torvald Nom and the two agree the Malazans are their shared enemy. He says he’s a Daru and just as he is about to launch into a long-winded bio, Karsa says it’s time to turn the log again.

SCENE 9

Karsa continues to work on the chains and log. Torvald tells him they have some time as Silgar will wait to travel with the Malazans to protect him from bandits (whom Nom says he helped organize). Karsa says he will kill Silgar. They are interrupted by the return of some Sunyd slaves. Karsa is disgusted with them, with their letting themselves be defeated, enslaved. One tells him they lost the old ways “long ago. Our own children slipping away in the night to wander south into the lowland, eager for the cursed lowland coins—the bits of metal around which life itself seems to revolve . . . some even returned to our valleys as scouts for the hunters . . . To be betrayed by our own children, this is what broke the Sunyd.” When Karsa says they should have killed those children, and that he will do it for them, another Sunyd calls his words empty and points out Karsa is a slave just like them. Karsa straddles the log and pulls on his chains and splits the log, freeing himself. He moves to kill the one who mocked him—Ganal—but Torvald warns him it will raise a cry and Ganal says if Karsa spares him they will stay quiet so he can make good his escape. Karsa frees Torvald for the courage he has shown. They escape the pit, with Karsa killing three guards. When Torvald suggest a direction to run, Karsa tells him he has no plans to flee, but he will avenge his friends and in so doing will create enough of a distraction for Nom to escape easily. Torvald leaves and Karsa finds a shack, kills the person in it, and looks for a weapon, coming across as he does so “a low altar . . . Some lowlander god, signified by a small clay statue—a boar, standing on its hind legs. The Teblor knocked it to the earthen floor, then shattered it with a single stomp of his heel.” He kills a few more and searches more huts before finding a Sunyd bloodsword, some Teblor armor made of bloodwood, and some blood-oil. He enters a house, kills most in it, then rapes a young girl he finds upstairs. He moves on house to house killing more, losing his awareness. When he comes back to full thought, he watches the Malazans ride out through the gate. He hears slavers enter the house below him and discuss how they think Karsa is heading for T’lan Pass where the Malazans will get him. He exits when they leave and makes his way across to the Malazan barracks where he is captured by a Malazan squad including Sergeant Cord, Limp, Shard, and Ebron—a mage who uses a sorcerous net. When Cord asks if it causes Karsa pain, Ebron says if it were Cord in it he’d be screaming and then dead, but Cord notes how Karsa isn’t even trembling. Silgar arrives and thanks Cord for capturing his “property,” but Cord says Karsa is now a Malazan prisoner, and also tells him “The Fist’s position on your slaving activities is well enough known. This is occupied territory—this is part of the Malazan Empire now . . . and we ain’t at war with these so-called Teblor.” He says Karsa will probably be sentenced to the otataral mines, in Cord’s homeland, which he says is rumored to be heading toward rebellion, though he doesn’t buy it. Silgar points out the Malazan hold “on this continent is more than precarious at the moment, now that your principal army is bogged down outside the walls of Pale . . . To so flout out local customs.” Cord interrupts, disgusted: “The Nathii custom has been to run and hide when the Teblor raid. Your studious, deliberate corruption of the Sunyd is unique, Silgar. Your destruction of that tribe was a business venture . . . The only flouting going on here is yours with Malazan law . . . What in Hood’s name do you think our company’s doing here, you perfumed piece of scum.” Tension rises and Ebron tells Silgar, whom he names as a Mael priest, to release his warren and Cord warns Silgar to call off his men or he’ll arrest him and send him to the mines with Karsa. Silgar send his men out then tries to bribe Cord. They are interrupted by the return of the other Malazans led by Captain Kindly, who arrests Silgar for bribery, and says to put him in a cell away from the bandit leader they just captured (Torvald). Kindly then asks what sort of spell Ebron is using on Karsa and Ebron says it’s used to “snare and stun dhenrabi” which stuns Kindly as he realizes how strong Karsa must be, and/or how resistant to magic. He tells them to leave Karsa enspelled and figure out how to load him on a wagon. Karsa can already feel the spell net weakening around him.

Amanda’s Reaction to Chapter Two

Straight away, in the extract by Kenemass Trybanos, we find out that there might well be a rather nasty beastie still lurking in the glacier mentioned in Chapter One. Ice always directs us towards Jaghut! This one sounds as though it might be a Tyrant: “terribly wounded, yet possessing formidable sorcery still.”

Heh, whenever Bairoth and Karsa call themselves by their full names it makes me grin—it’s sort of like argumentative children being referred to by first name and surname by their exasperated parents!

It is really odd to see Karsa express compassion towards the dogs in the pack, especially the three-legged beast. It’s sort of like those men who beat their wives and yet show affection to their pets. At least it shows that he has more facets to his character than just “faster, pussycat, kill, kill!”

“Pahlk had named it Bone Pass”—more references to bones/T’lan Imass?

Here’s a quick question to you all… It’s taken me right to the last minute to pick up HoC and start work on Chapter Two (makes me nervous I won’t do it justice, especially after all the praise from y’all about me managing to pick up a few points in Chapter One—my head definitely expanded) I’ve hesitated at picking up the novel because, despite the fact it’s a Malazan novel and even taking into account how much I trust Erikson, I don’t enjoy Karsa. At all. I’m struggling to pull together the will to continue reading about him. So—do you ever have trouble reading a novel because of one character? Did you find the novel fulfilling despite that character? What is your usual approach—do you struggle through and hope it’s worth it, or do you decide to put down a novel when a character frustrates you so much?

*ahem* Let’s move along, shall we?

The carvings on the walls of the cave are interesting, non? And relate to Icarium! From what I can tell here, someone—and I can’t guess who—has decided to sunder the original tribe of the Teblor (the Toblakai?), because they were being hounded by the T’lan Imass. So the Laws of Isolation were invoked—provided by Icarium. Ack. My head is full of jigsaw puzzle pieces and I’m trying to force them together….

“To survive, we must forget. So Icarium told us.” Because Icarium knows that this is what he does?

Well, we certainly have an explanation of why the Teblor act as they do! They are a race of people who have actively chosen to take a step backwards to more primitive times. “Legends that spoke of feuds, of murders and rapes. We must return to those terrible times.”

I think it would have been very interesting to see Bairoth in the cave with Karsa as he reads the words. Delum follows too easily and doesn’t have the intelligence of Bairoth, merely says: “As you say, Karsa Orlong” when Karsa shrugs off the words and says they have no meaning. Aha! We soon have a conversation between Karsa and Bairoth, where the latter believes there is truth to the words.

Karsa is a single-minded beast, isn’t he? You have to sort of admire that dedication: “The time has come, I now say, to fave that challenge. The Teblor must rise once more.” And he’s not shy about believing himself to be the one to lead them!

It’s interesting as well that Bairoth is the main person to realise that, actually, Synyg is probably the most worthy of the tribe—and that Pahlk more than likely lied about his role in the “raid” on Silver Lake (something that has already been hinted at): “Your father is not weak, Karsa Orlong. If there are doubts to speak of here and now, they concern Pahlk and his heroic raid to Silver Lake.” Not sure if it’s just me, but I’m almost imagining Bairoth using air quotation marks when he says “heroic.” *grins*

I like the way that Karsa immediately sees the raid on Sunyd by the lowlanders as a strike against the whole of the Teblor. “We journey to Silver Lake not as Uryd, but as Teblor.”

Gosh, you would need to hate someone or find them utterly dangerous to drop a rock on them for all eternity, wouldn’t you? The Forkassal? That reminds me of something, in the same way that Teblor reminded me of Toblakai. Something we’ve had brief reference to before…. Hang on while I flick through my notes. *minutes tick by* Aha! Forkassal—close to Forkrul Assail (not sure if that’s spelled correctly?) What I like here is the way Erikson is showing the way that language can change and shift over many hundreds of years. Words become bastardized, and shift slightly so that you can see the reflection of what it might be.

Here is an emphasis, as well, of the language changes: “What, Karsa Orlong, do you recall of that tale? It was so brief, nothing more than torn pieces. The elders themselves admitted that most of it had been lost long ago, before the Seven awoke.”

The Spirit Wars—Jaghut verses T’lan Imass? Since they make mention again of “but one force” remaining, which could be the Jaghut holed up in the glacier….

Does it say something about the Teblor society that they assume the Forkassal must be male?

Huh… There are some things to like about Karsa—his odd insight at times is very valuable, and something I guess I will want to keep in mind when he comes over all barbarian again! “No, Bairoth Gild, she has known enough pressure that was not her own. I do not think she would be touched, not for a long time, perhaps never again.”

Erikson is doing well to make us immediately sympathetic towards the Forkassal: “She mocks her own sorry condition. This, her first emotion upon being freed. Embarrassment, yet finding the humour within it.”

And then we’re back to barbarianism, as Karsa declares a vow against the T’lan Imass who imprisoned the Forkassal—without knowing who or what the T’lan Imass are. This gave me a little chuckle, since I know what he’s pitted himself against. But you know something? I’m also slightly worried that he could keep that vow! Karsa really is a force of nature, isn’t he?

“I am Forkrul Assail, young warrior—not a demon. I am named Calm, a Bringer of Peace, and I warn you, the desire to deliver it is very strong in me at the moment.”

I confess to being slightly smug at having my suspicions confirmed! Also, that bringing of peace—sounds a lot like death, non? [Bill: What, after all, is more “peaceful”?]

Have to say, if Icarium and the T’lan Imass put Calm under a rock, it makes me think she should have stayed there….

Poor Delum—for his loyalty, he now suffers from brain leakage.

Hahaha, not sure what it is about that description of the dogs suffering the manhandling with miserable expressions, but it made me giggle. I could see these warlike hounds with indignant looks on their faces as they find themselves cooed over. Laughter but then slight disgust at myself, because poor Delum is the source.

Karsa’s pragmatism over Delum’s injury is ice cold, but also very practical—why blame himself for an error that Delum made? But, he really is ice cold!

“Know you no grief, War-leader?” he asked in a whisper.

“No, he is not dead.”

“Better he were!” Bairoth snapped.

“Then kill him.”

Hmm, Karsa is no more likeable than before, but I am definitely coming to admire him—especially with this exchange with Bairoth. He is intelligent to know that the trip to Silver Lake could not be achieved without danger and scars, and teaches Bairoth what it means to follow. I find Bairoth’s attempts to jibe Karsa with thoughts of Dayliss incredibly clumsy, at this point—the attack of someone who can’t actually find a better comeback.

Definitely otataral protection from sorcery, yes? That is what allows Karsa to chop the four mages to pieces.

“Karsa Orlong,” Bairoth had to shout to be heard over the roar rising from far below, “someone—an ancient god, perhaps—has broken a mountain in half. That notch, it was not carved by water. No, it has the look of having been cut by a giant axe. And the wound…bleeds.” I might be clutching at straws here, especially because an axe is referred to—but this immediately made me think about Caladan Brood and his hammer. Completely off track?

Our first cinematic scene from Erikson in the new book. *grins* Karsa throwing that lone rock down the steep path of shale and scree, and then it all sliding away to reveal stairs of bone. Very cool! “Tens of thousands have died to make this. Tens of tens.” I wonder what army created these stairs of bone.

Hmm, strange sort of disconnect between the two or so weeks that was mentioned as being the distance to Silver Lake, and then this quote, “The Teblor’s supply of food quickly dwindled, the horses growing leaner on a diet of blueleaf, cullan moss and bitter vine…” Makes it sound like they’ve been on the road for months! Also, just contemplate those plant names—so solid and realistic, and really adding to the overall “feel” of a novel well-imagined.

It is a sad and poignant scene as Bairoth paints Delum’s face with the death mask, knowing that his companion will not survive the day. He does him honour, and it is a shame that Karsa cannot see it as such. “You speak nonsense, Bairoth Gild.”

Ha! A nice little bit of amusing foreshadow as Bairoth says, “Warleader, how many lowlander generations have passed since Pahlk’s raid?” and then the charge by the three Teblor on what is actually a town. Also, commentary on Karsa’s state of mind when he doesn’t see it as any more of a challenge than the few farmsteads he thought he’d be charging.

Geez! Havoc is twenty-six hands? That gives a sobering idea of just how large the Teblor are! For those not in the know, a standard pony goes up to fourteen hands. And Shire horses—the big heavy horses—clock in at eighteen hands. Twenty-six is simply ENORMOUS.

As mentioned in Chapter One, it is hard to see the word “children” in reference to the lowlanders—makes the carnage and visceral battle scenes difficult to read.

This really is an eye-opening scene, watching as Karsa and his companions tear the lowlanders to pieces. “Batting aside the occasional, floundering pike, they slaughtered the children the dogs had not already taken down, in the passage of twenty heartbeats.”

Ten paces beyond lay Gnaw, leaving his own blood-trail as, back legs dragging, he continued towards the body of his mate. He raised his head upon seeing Karsa. Pleading eyes fixed on the warleader’s.

Awwww.

Another little surprise concerning the Teblor physiology—they have four lungs, rather than two!

The tattooed lowlander SOUNDS like a Malazan—the cadence of the speech, the lack of awe and respect for Karsa, the slight amusement, the reference to Oponn.

When Karsa says that he is prepared to answer questions about his tribe and, in so doing, condemns Bairoth, he is again showing that cold practicality.

Wow, Karsa’s arrogance and spirit leaves me breathless. He is chained and wounded; he feels the abandonment of his fellow Uryds, and yet he still finds it within him to jibe the guard—and jibe him with words that feel like truth: “When I attacked your party on the ridge, you fled. Left the ones who had hired you to their fates. You fled, as would a coward, a broken man. And this is why you are here, not to tell me things, but because you cannot help yourself. You seek the pleasure of gloating, yet you devour yourself inside, and so feel no true satisfaction.”

I marvel at the fact that in a mere page, Erikson can make me feel respect for the Sunyd who invites Karsa to drown him. Right there. That’s why I read Malazan books.

Tarvald Nom! A relative of Rallick Nom? *grins*

Once again Erikson turns things on its head. We’ve been decrying the behaviour of the Teblor as they rape, murder and pillage, then, with Tarvald Nom’s words, we see it as an act of mercy instead—rather than committing slow torture.

I mutter “stupidity” at the idea that Karsa has successfully managed to escape and now wishes to commit vengeance on those who killed his companions. I mean, it’s sort of nice and all, that he wants to avenge their honour—but why not just make a run for it and come back with a whole tribe to back you up?!

“A low altar caught Kara’s attention. Some lowlander god, signified by a small clay stature—a boar, standing on its hind legs.” Fener?

Oh, now these are definitely Malazans, who have managed to capture Karsa—and I feel comfort just by having them around, even though I don’t know them properly yet. And mention of Mott Wood (and, indirectly, the Mott Irregulars, who need clearing out!)

The otataral mines of Cord’s homeland? The same otataral mines that Felisin was sent to?

I have to say, reaching the end of Chapter Two, that I am very much back in the swing of things, and happy to follow Karsa’s journey. I’m slightly relieved about that, to be honest! Was wondering how I’d get through a book where I couldn’t bear reading about one of the characters!

Bill’s Reaction to Chapter Two:

So we get a bit more complexity to the sacrifices of the Teblor children to the Faces—some of them at least, if not most, were born deformed. Though before we consider the sacrifices a “mercy” or a sacrifice of one about to die anyway, note that some of the deformities were simply an extra finger or two.

More evidence of Karsa’s lack of insight and insularity—his belief that his friends view his father and his grandfather in the same fashion as he does: as weak and as heroic respectively.

Bairoth’s “prayer” that Karsa never know doubt fits into a running theme in the series—the nature (often sinister) of certainty. Bairoth speaks to the idea more bluntly a few lines later when he makes a link between wisdom and lack of certainty and calls the early “heroes” of the Teblor “monsters” for “they were strangers to uncertainty.” We’ll soon start to see as Karsa begins to “know doubt.”

We’ve had brief, very brief, mention of the Forkrul Assail in earlier books—Mappo called them “the least known of the Elder Races” in Deadhouse Gates. Beyond that we simply get their name a handful of times. This is our first real introduction to them then, and it’s a good idea to keep in mind their speed, their deadliness (think of what we’ve seen Karsa do), and their focus on “peace,” which as Amanda pointed out sounds a lot like a synonym for death. Not to mention of course their endurance and will—think of Calm entombed under the rock all those years and still sane. Or at least, seemingly so. (and we will meet Calm again). Consider her hand: “chewed, clawed and gnawed at; though, it seemed, never broken.”

Poor Delum—he sees clearly what might happen and rather than get rewarded for his insight and intelligence, he’s robbed of it.

Bit chilling of a line from Karsa, eh? “There is no value in peace.”

So as a reader, I’d say we’re probably as surprised as Bairoth by Karsa’s unexpected tenderness and insight toward Calm when Bairoth moves to help her. We had a glimpse of this earlier when the Rathyd girl mentioned his surprising gentleness (a moment’s “sensitivity” quickly contrasted by his calling her Dayliss), so this isn’t a complete anomaly, but it is a surprise. It does, however, set us up for the possibility of there being more to Karsa than we’ve seen so far and thus the possibility of growth on his part.

Note her “amusement” when they call themselves “Teblor.” And especially note her line to Karsa about how her “enemies”—the T’lan Imass—”will not leave you.” Another reference to the origin of the Seven Gods.

Just how many prophecies can one Toblakai get involved with? The prophecy of he who will unify his people, the prophecy by the sacrificed that only one of the three friends will return (“The Toblakai who lived!”), and now Calm’s prophecy that “Karsa has been chosen. If I was to tell you even the little that I sense of his ultimate purpose, you would kill him . . . There will come a time when he stands poised to change the world. And when that time comes, I will be there.” What is this dread purpose? Have we see seen it yet in Deadhouse? Well, Karsa will do a lot of things in this series. A lot. But I’ll say that one of his last and largest is foreshadowed in this chapter in very specific fashion.

Earlier we wondered who the dog was—was it Trull? Was it Karsa? Now we have a literal man/dog—Delum. Is he the dog of the metaphor?

More of Karsa’s certainty and lack of doubt—his inability to understand the concept of regret. A frightening lack in one so powerful.

Bairoth’s words to Karsa are a clear echo of the earlier prophecy that only one of them will return.

Walking a path atop bones—well, at least there’s nothing foreboding about that….

Considering what we’ve seen of the Teblor insularity and what they will discover at Silver Lake, I like the description of Bairoth and Karsa’s descent: “Beside them, the river continued its fall . . . spreading out to blind them to the valley below and the skies above. Their world had narrowed to the endless bones under their moccasins and the sheer wall of the cliff.” It’s a nice visual depiction of their knowledge state.

A knowledge state sorely incomplete, as evidenced by their highly ironic statement with regard to the lowlanders and the idea they may have worshiped Calm: “That demon was not a god . . . The Faces in the Rock are true gods. There is no comparison to be made . . . The lowlanders are foolish creatures whilst the Teblor are not. The lowlanders are children and are susceptible to self-deception.” Cough, cough, Seven Gods, cough….

Once again Karsa closes his mind to the truth as Damisk (the escaped guard) tells him of the reality of Pahlk’s “raid” on the farm. Karsa’s line to Damisk: “It hurts my ears” is in reference to Damisk’s use of the Teblor tongue, but can clearly refer as well to the truth. How long can he deny the realities of the world he’s entered?

Here we go—another Karsa prophecy—turns out the priest spoke of the one “who stalked their dreams like Hood’s own Knight.”

Karsa and chains. Amanda pointed out an earlier chain reference—be prepared for a lot more.

Nom. Nom. Now why does that name sound so familiar….

So the barbaric children-slaying, limb-chopping Teblor don’t countenance torture or slavery. Yet the “civilized” Nathii do both and “have made the infliction of suffering an art” according to Torvald Nom. There goes simpliclity….

Okay, take this out of the fantasy epic and place it in a textbook or oral history and we can see some of the depths here in Erikson’s writing: “Lost? Yes, long ago. Our own children slipping away in the night to wander south into the lowlands, eager for the cursed lowlander coins—the bits of metal around which life itself seems to revolve. Sorely used, were our children—some even returned to our valleys, as scouts for the hunters. The secret groves were burned down, our horses slain . . . [our children] are scattered, many fallen . . . some have traveled great distances, to the great cities . . . Our tribe is no more.”

As difficult as it is to like Karsa, it’s equally as difficult to dislike Torvald. Luckily for us.

If the earlier scene in the Rathyd village was more complex than simple rape, the same cannot be said I’d say of Karsa and the young girl he comes across. This is clearly rape and is about as risky a move as Erikson can make, I’d say. (It reminds me somewhat of a similar scene in Stephen Donaldson’s Covenant series—one of my favorites and highly recommended.) What does this scene do to the reading experience?

Not to mention the rampant gory bloodshed. I can’t say I “like” it, but Erikson has a very effective use of language in these scenes I think when he keeps having Karsa refer to his slain as “children,” which causes an instinctive clench of the gut and sense of revulsion I’d say in most readers, followed by a sense of relief as we keep telling ourselves children doesn’t really equal children, but then almost immediately upon that we get the bounty hunter referring to Merchant Balantis’ two dead children. So yes Virginia, Karsa is a child-slayer. It’s as I say, highly effective in how our emotions are turned so fast.

In case anyone is keeping count, Karsa has declared the Nathii his enemies, the T’lan Imass his enemies, and now the Malazans his enemies.

Another example of the Malazan Empire being in some ways an improvement as a conquering group—the banning of slavery so freely practiced by the Nathii.

What is it about these Mael priests? Why so slimy?

I’m not sure why, by this point, anyone might not be all that clear that Karsa is a supreme badass, but just in case, think of what we learned of dhenrabi in prior books and consider that the spell that is just barely holding Karsa (and already weakening) was meant for those creatures. And another organ-sound ending: Not long now….

As for Amanda’s question regarding unlikable characters—I can’t recall if I’ve given up on books because I didn’t like a character. If I have, I’d guess it was as much a fault of technique as of character-building. A good author can compel a reader forward with a despicable character, I like to think. I have given up on books because I didn’t care about characters, but that isn’t quite the same thing. Here, Erikson is definitely pushing the edge with Karsa, but it’s also perhaps a bit less risky than it seems on the surface. After all, he does have a built-in audience already heavily invested in continuing forward. Had we started with HoC and with Karsa, I can see him losing a lot, and I mean a lot, of potential readers. But having gone through several very large tomes, I can’t see many readers jumping ship in the first few hundred pages of book four of a series they’ve spent lots and lots of time reading. And of course, beyond simple investment, they know Erikson tends to pay off, so they’re more willing to “suffer through” (if that’s how they feel about it) Karsa to get to the pay off. That said, I think he certainly risks annoying a heck of a lot of his faithful readers, and so I think it’s a very good thing that it isn’t long before we start to see some growth in Karsa.

Bill Capossere writes short stories and essays, plays ultimate frisbee, teaches as an adjunct English instructor at several local colleges, and writes SF/F reviews for fantasyliterature.com.

Amanda Rutter contributes reviews and a regular World Wide Wednesday post to fantasyliterature.com, as well as reviews for her own site floortoceilingbooks.com (covering more genres than just speculative), Vector Reviews and Hub magazine.

Man, I love Karsa. Yes, he’s a nasty guy, and in real life not someone you’d likely want to be around, but his courage and determination—not to mention his prowess—are all commendable. He’s pragmatic, suprisingly insightful. And we’ve already seen that he’s capable of compassion (I just got a little misty thinking of TCG.) His biggest flaw might be his own self-assurance, but it’s also quite possibly his greatest strength.

Plus, he has the best perhaps the best catchphrase in the series: “Too many words.” (Right behind “Witness!”)

I think that Karsa annoys the reader because there’s elements of transgression against the usual expectations of the reader in what they’re reading.

Many fantasy readers go into the books they read with a general idea of what they’ll be reading: magic, some violent conflicts, perhaps war, some sad things, some happy things, perhaps some soliloquies and/or philosophy and adventure.

They’re not expecting rape, they’re not expecting xenocide, extreme aggression, contempt or characters who aren’t already within their comfort zones. Karsa is so wildly different from the general crop of fantasy characters since Conan that it’s hard for many readers to adjust to that – just like with Thomas Covenant. The two characters shatter expectations and that’s often a big hurdle for a reader looking to escape or looking for books within their usual wheelhouse. Those who trust Erikson and those who understand where the tradition of the “might makes right” barbarian comes from can adjust to Karsa (Beowulf, Gilgamesh, Achilles etc.).

I also think part of the backlash against Karsa comes from people in real life having problems with jocks or people who have extraordinary physical gifts and an attitude to go with them. It takes some stretching to relate Karsa to the real world, but I genuinely think it does happen on some level with some readers.

Long chapter is loooooong. Luckily the remainder of the book is broken down into more manageable chunks.

In case you missed it, Karsa stepping on Fener’s statue – massive file. I think there are very few scenes as heavy in their ‘how did I miss that’ magnitude as this one. ‘crossing blades with his own vengeance’ is the only other I can think of.

The use of prophecy in this book is fairly unusual, it rings slightly discordant on a reread as it isn’t something Erickson has made much use of throughout the rest of the series. Spoilers:

We only really see one of them fulfilled (if Calm’s words are actually linked to the foreshadowing, which raises a bunch of questions about the last book, since it implies knowledge of plans that the FA don’t seem to do much about) and the rest are pretty much forgotten. Bairoth and Delum die, but I don’t recall Karsa ever journeying back home. Given that SE’s second planned trilogy has been tentatively named the Toblakai trilogy, there may still be more to Karsa’s story though.

Karsa does grow on you. You may not ever grow to like him as a character, but he makes interesting reading. Characters that don’t interest you at all are much worse than ones that make you uncomfortable. I’ve given up on few series in my life, most of the times it’s because I just couldn’t find it in me to care about the characters. What’s interesting is that Karsa isn’t written as a ‘love-to-hate’ character, or even bad-guy-turns-good character. He grows and gains subtlety, but I don’t think he can ever be described as being reformed. The closest comparison I can think of is Stover’s Caine, who is thoroughly engaging while also being a hardass bastard.

There’s a throw back in this chapter to a previous discussion about whether the T’lan Imass consider Icarium a Jaghut – here we have proof they encountered him and decided not to attack.

Also Torvald ****ing Nom!

Karsa’s reasoning that it didn’t matter if he told the slavers about his tribal lands was “interesting” logic on his part. The “better to live to fight another day” aspect of it shows some fairly advanced reasoning for him to this point. Although his idea that his brothers had abandoned him by dying did seem a tad self centered. But then, like Amanda mentioned, after escaping he doesn’t go get warn the tribe he just attacks again–so much for reasoning.

I really liked the introduction of Calm and the Forkrul Assail–another ancient race introduced and brought to life as it were. The immediate turning around of “Bringer of Peace” into bringer of death was nicely done. And, we’ve seen how Karsa & co. carve through everything in their path–Calm just takes them out with little effort–interesting.

By the end of chapter two, I found myself admiring Karsa’s resoluteness and unflappable belief in himself. I don’t like him, but his storyline does keep getting more interesting. Kind of like watching a train wreck–it’s hard to look away.

The gradual introduction of known elements (Malazans and a Nom) are reassuring that we are reapproaching the main story.

I also really liked the Icarium references. He basically gave the Teblor a new code to live by that would let them exist and prevent massive inbreeding. Also, the T’lan knew they couldn’t defeat him and so didn’t try. That says a lot given what we know of their single-mindedness.

@bill: What is it about these Mael priests? Why so slimy?

Sure provide illustration for why some of the ascendants we see feel the way they do about worshippers don’t they?

Since, despite the nice Seattle weather, I appear to be cast as the curmugeon, I’ll answer Amanda’s question.

I have quit reading books over unlikable protagonists. Why would I want to keep spending my sparse time reading about someone I don’t like? Karsa is one of the reasons I abandoned the Malazan series, apart from Ian Esslenmont’s standalone novels. I don’t want to read about Karsa’s the rise to glory. The man’s a karma Houdini.

But, if you do want to keep reading you can always skip his chapters. So much of Erikson’s work is compartmentalized that skiping entire POV characters is very possible. You may miss some of his plot seeds but you’ll have a more enjoyable reading experience.

I think Bill is right, with the built-in audience Erickson has/had at this point, he can afford to do things that people will hate but sheer momentum will keep the readers reading. Most people won’t give up on a series after six or seven books, but I’m odd.

Good luck and I mean that sincerely.

Thanks Amanda and Bill.

I’ll just jump right in to Amanda’s question. Amanda, I had the problem you mentioned with this exact character and book. My first time through, I really did not like Karsa and was hoping to see him experience a painful and humiliating death. I did respect his formidability and pragmatism, but I just didn’t like him. It was a challenge to keep on going.

I noticed my attitude towards Karsa started to change (and some sympathy started to develop) once he was captured and we encounter the slavers. I knew how Erikson was subtly trying to manipulate the reader, and was trying to be quite resistant to it, in relation to our attitudes toward Karsa.

I decided to power through this arc, as I had other Malazan vets who had encouraged me to soldier on through the first part of HoC, and that things would get better. Obviously, near the end of Chapter 2 it became easier for you. I would suggest that the most difficult (for the reader to read through, anyway) and irritating part of Karsa’s story arc has passed. But, there’s still a whole lot more, and it’s definitely interesting.

The thing about Karsa, I find it difficult to imagine that he wouldn’t stand out in most readers’ recollections of the Malazan books. He definitely appears to be one of Erikson’s more polarizing characters…

Amanda,

As you say, the minute we get actual Malazan soldiers we start to feel less disoriented. Suddenly this is about a familiar world and setting.

But also notice these couple key quotes: that Seven Cities “is rumored to be heading toward rebellion“, and that the “[Malazan] principal army is bogged down outside the walls of Pale“. This places us in the continent of Genabackis and before the fall of Pale.

Amanda, I probably have quit books because I did not like a character although it is never the only reason. It is actually a problem for me reading George Martin, I dislike some of his POV characters, and the way they act and as a result I have never managed to finish any of the asoiaf books in one try. But I keep at them because the pay-off is there, and the motivation is kept up by all the people that are really enthusiastic about the books.

@bill:

You used the word Toblakai instead of Teblor. Let’s not spoil this for Amanda, ‘m kay? Since this is about a first read ‘Oh!’ moment… ;-)

And the Ashok Regiment has entered the building! Welcome Sergeant Cord, Ebron, Shard and Limp(!). And Captain Kindly… :D

I always liked the thing about that farmsteads having grown into a Walled Town since Pahlk ‘visited’. Although since Pahlk has been glorifying his own experiences, I doubt it was just a couple of farmsteads in his time, and that there was already a bigger community there back then.

Oh, and hello Silgar….

Hi Fiddler,

Since Amanda made the connection already to Toblakai, I felt it OK to use the term but tried to keep it as if here “a” Toblakai but not make it clear he was “Toblakai” the character. I think we’re still safe as she hasn’t drawn that conclusion yet, but I can see your point

Bill

@bill:

Fair enough. :)

Except maybe that in the last thread some people stated the fact right out.

Maybe I’m too protective. Not that Amanda needs it, but I love reading her ‘Oh!’ moments ;)

I think Ericson does a “benighted” viewpoint very well, here.

Amanda:

Take note of Captain Kindly, whom you just met. He provides some lighthearted moments throughout the series. For me, Kindly (along with his Lieutenant you haven’t met yet) is one of the few bright spots in Dust of Dreams that made it somewhat bearable.

@6

your loss. it’s like quitting a biography of an interesting historical person because they were arrogant/petulant/annoying/bullying as a teenager. the joy of karsa is not about what he does or how Bad-Ass(tm) he is — it is about his growth. Karsa has one of the most tender life affirming moments in the whole entire series. skipping him now just elimates any chance you have to experience that. it is really a shame. I hope nobody else takes your advice.

I also don’t believe you can read the whole series w/o reading his story arc. He is too central to the whole series (in particular in book 7 and 8)

Jeez I frickin hated Karsa when I first read HoC, actually thought SE had lost it at one point, and did wonder how I was going to continue reading…

stick in there Amanda, you just may come to love the big oaf, and always always, trust in SE.

@6 “skip chapters” are you mad sir?

@@.-@ Icarium’s plan didn’t prevent massive inbreeding – it caused it, but for a reason. The Teblor’s ancestors circa the spirit wars had become weak and lost their way of life. They had been seduced by cities and gold and most likely weren’t of pure blood – similar to the Sunyd of the modern Teblor and heading towards the same fate. In animal husbandry selective inbreeding is used to strengthen specific traits unique to the bloodline. In this case, it was being used to try and isolate the pure Teblor bloodlines. Of course if you overdo the inbreeding then genetic flaws also come to the fore, as can be seen by how many Teblor children are born deformed. By combining inbreeding with the survival of the fittest lifestyle of the original teblor meant that weaker Teblor would be routinely culled and stronger bloodlines would be spread through rape (thereby preventing possible cultural contamination). We see it working in the first chapter, two or three generations from now most of the Uryd children would be some combination of Karsa, Bairoth and Delum – who are probably the closest to the original Teblor. What is strange is that it was Icarium who put the whole system into action. We’ve seen before how ascendants can care very little for the lives of non-ascendants, but Icarium is generally uninvolved in such manipulation and it seem unlike him to suggest such a brutal course of action.

Whenever I post a comment I get an error message saying JFolder cannot delete a folder. I’m reasonably sure that shouldn’t be happening, so maybe an admin of some kind should look into that.

(mild structural spoilers for HoC below)

FWIW, I’ve only read the Karsa section once, and at that, only on after finishing the book the first time –I read about half of it the first time I had the book, got about halfway through with Karsa’s section and started skipping ahead looking for an sign that I would get away from him, and ended up just reading the rest of the book from there.

I ended up going back and finishing his section later, but I’ve never bothered on re-reads; life is too short to spend that much concentrated time with an asshole. That said, I think that Karsa is a worthwhile character, his story is interesting, and what Erikson’s attempting is worthwhile. The problem to my mind is largely structural. I understand why the book is structured the way it is, but I can’t help but wish his section had been broken up by something else.

I liked Karsa from the start. And then I started liking him even more, and then he became my favorite character.

if this posts correctly it’ll be a miracle…

The Problem of Karsa Orlong

To say that, among all the characters portrayed in The Malazan Book of the Fallen, Karsa Orlong has proved the most divisive among readers of the series is probably beyond refute. Discussions arise regarding this character again and again, and as the debate returns in this TOR re-read, the question of my purpose in creating this character could probably be addressed: so I will.

Consider this an essay, then. The problem posed by Karsa and how

readers perceive him will, for me, find its answers from a range of angles; from the Fantasy genre itself, to anthropology, history, cultural identity and its features, to the structure of the series (and the novel in question) and, eventually, to the expectations that fantasy readers bring to a fantasy novel. You may note something of an ellipse in that

list, but that’s how I think so bear with me.

Historically within the genre the role of the ‘barbarians’ has roughly split into two morally laden strains. On the one hand they are the ‘dark horde’ threatening civilization; while on the other they are the savage made noble by the absence of civilization. In the matter of Karsa Orlong, we can for the moment disregard the former and concentrate instead on the noble savage trope – such barbarians are purer of spirit, unsullied and uncorrupt; while their justice may be rough, it is still just.

One could call it the ‘play-ground wish-fulfillment’ motif, where

prowess is bound to fairness and punishment is always righteous. The obvious, almost definitive example of this is R.E.Howard’s Conan, but we can take a more fundamental approach and consider this ‘barbarian’ trope as representing the ‘other,’ but a cleaned-up version

intended to invite sympathy. In this invitation there must be a subtle compact between creator and reader, and to list its details can be rather enlightening, so here goes.

We are not the ‘other,’ and this barbarian’s world is therefore exotic, even as it harkens back to a pre-civilized, Edenic proximity. The

barbarian’s world is a harsh one, a true struggle for existence, but this

struggle is what hones proper virtues (‘proper’ in the sense of readily

agreeable virtues, such as loyalty, courage, integrity, and the value of honest labour). Against this we need an opposing force; in this case ‘civilization,’ characterized by deceit, decadence, conspiracy, and consort with evil forces including tyranny: civilization represents, therefore, the loss of freedom (with slavery the most direct manifestation of that, brutally represented in chains and other forms of imprisonment). In essence, then, we as readers are invited to the side of the ‘other,’ the one standing in opposition to civilization. Yet … we readers are ‘civilized.’ We are, in fact, the decadent products of a culture that has not only accepted the loss of freedom, but in fact codifies that loss to ease our discomfort (taxes, wage-slavery, etc). In this manner, we are offered the ‘escapist’ gift of Fantasy; but implicit in this is the notion that a) we need to escape; and b) that civilization is, at its core, evil.

[So, is it not ironic that Leo Grin (a great fan of R.E. Howard) attacks modern fantasy as nihilistic? This man’s incomprehension of Howard’s own nihilism and anarchic rejection of civilization is, simply, jaw-dropping. Amusing digression ends.]

This brings me (and I can almost hear the groans) to anthropology, although one could approach the notion of the ‘other’ from a whole host of theoretical stances, including mytho-Jungian, sociological, psychological, etc. The point is, the ‘other’ is universal to the human condition: it exists in every culture. I won’t go into too much detail

here, since the singular point I want to make is that the notion of the ‘other’ is implicitly arrogant. Most cultures give themselves a collective identity (the ‘us’) and often attribute to themselves a name that means something like ‘the people,’ implying that the ‘others’ are not quite people. This has of course justified all manner of conflict and subjugation, from ancient times to the present. Accordingly, it is not

unique to ‘civilization’ per se but to all cultures, regardless of their

technological level and social organization. To be the (one and only) ‘people’ is an arrogant assertion: defined in terms of specific habits, behaviours, physical features, language, religion, and so on, but ultimately profoundly conceited in its essential world-view. By this means all manner of atrocity is possible when dealing with the ‘other’ (and all militaries impose psychological ritual to ensure that the soldier sees the enemy as an ‘other’ and therefore less than human and therefore permissible to kill).

[It’s not all grim: the notion of ‘us’ has essential virtues in collective identity, through the sharing of values, community cohesion, and so on; but it’s probably fair to say that the pay-off is not quite a balanced one, given that the inherent weakness of ‘us’ hints at fundamental flaws in that kind of thinking, even if the notion of ‘us’ also happens to be necessary for a society to function]

Barbarian societies can be as arrogant as civilized ones: the only difference is in the expression of that arrogance. At its core it’s all one, and seems to be a characteristic of the human condition (to this day, for all of our efforts at self-identifying ourselves as a global culture, we continue to impose borders, define select privileges, exercise extortion of weaker peoples, and in the rejection of one community (the neighbourhood) we raise countless others, defined by political afiliation, religion, skin colour or whatever).

There are other implicit judgements to the ‘other.’ Among the Romans the ‘barbaric’ other was not viewed as less-than-human, but in terms of

inherent weakness (of their culture). This justified subjugating them, occupying their lands, and enslaving as many of them as was economically possible. The notion of being ‘Roman’ was considered the height of civilized and cultural identity (though it came back to bite their Roman asses). [incidentally, and at the risk of offense, this is what made the teachings of Jesus so revolutionary, as they directly

challenged the accepted definitions of self-identity and the institutions of authority in place to maintain them, only to be later co-opted and segmented into rival sects – more us’s and more them’s – in direct defiance of those very teachings. But one can also argue about

the ‘us’ of believers and the ‘them’ of non-believers … I sense a vortex ahead so will end digression there]. This Roman stance was the notion of might-as-right and is of course yet another expression of arrogance. Later on, with the (re)-institution of slavery, drawing from Africa, the notion of less-than-human became the dominant ‘justification’ for brutalizing the ‘other.’ One can then turn to the treatment of Jews in Europe, and so on. The point is: history is the study of ‘us’ and ‘them’ and little else.

So, how does all this relate to Karsa Orlong? Well, as has been noted,

there was something of the need to prove that I could sustain a single

narrative going on (or so I recall, the sense of being pissed off about

something is always short-lived and usually ephemeral, although the answer to it can prove far-reaching, as is certainly the case with Karsa); but obviously more was going on. I wanted to address the

fantasy trope of the ‘barbarian’ (from the north, no less, and isn’t it curious how so many heroic barbarians come down from the north?), but do so in recognition of demonstrable truths about warrior-based societies, as expressed in that intractable sense of superiority and its arrogant expression; and in recognizing the implicit ‘invitation’ to the reader (into a civilization-rejecting, civilization-hating barbarian ‘hero’), I wanted to, via a very close and therefore truncated point of view, make it damned uncomfortable in its ‘reality,’ and thereby comment on what I saw (and see) as a fundamentally nihilistic fantasy trope: the pure and noble barbarian. Because, whether recognized or not, that fantasy barbarian hero constitutes a rather backhanded attack on the very civilization that produces people with the leisure time to read (and read escapist literature at that).

Within the scope of Karsa’s culture, he holds to his code of integrity and honour, even if they are initially friable in their assumptions (but then, so are all of our assumptions about ‘us’ and about the ‘other’). We

observe the details of that culture, revealed bit by bit – with plenty of hints as to its flawed beliefs – and with each detail, we as readers are pushed further away from our own civilized sensibilities.

In one sense, consider Karsa’s tale at the opening of House of Chains as a walk back through time, to the world of, say, Beowulf. As much as we

find Beowulf entertaining as a poem, and can even admire it, its ‘barbaric’ sensibilities are profoundly alien to us. Here we have

a hero (Beowulf) who shows up as a stranger, only to spend an evening bragging about his superiority over all others, before ultimately usurping Hrothgar’s kingdom … if I may humbly ask this: if you saw Karsa Orlong sitting at Hrothgar’s table that night would you feel him out of place?

The question is: how far from our own sensibilities can we be pushed before it’s too much? Is it his brazen arrogance? Is it the culturally-acceptable rapes? Is it the slaughter of townsfolk, the rejection of Karsa’s companions due to their failures – their weaknesses? Is it his unquenchable self-belief? His need for vengeance? His excessive vows pronounced seemingly without thought? His rejection of civilization? His rejection of enslavement? In other words, where in that Conanesque code of conduct do we reel back a step, shaking our heads?

One of the areas of serious disturbance among readers is, quite understandably, the rape scenes. There is a counterpoint to these, found later in the novel, that includes Karsa’s very direct answer to it, which while on the surface may seem contradictory to his nature, is in fact anything but. Another area is the use of the word ‘children’ when voicing his exploits of slaughter (but then, if child-slaying is a universal

taboo, what does that say about our culture, with its missing children; and what does it say about our foreign policies and/or our fanatic religious beliefs, that see children killed every day; or our notions of wealth, that see entire countries left to starve?).

Having established this tight, myopic point of view of the ‘classic’ barbarian (reasonable for an isolated people of remote mountain regions) – and structuring the tale empty of overt authorial

judgement yet relentless in its detail, one might then expect to see me take the ‘dark horde’ route and offer up civilization as the beacon of virtue and enlightenment. But then … maybe Howard had a point? For all that his nihilistic rejection of civilization, personified in the Hyborian Tales of Conan, is an invitation to despair (like a bullet to the head), it cannot be dismissed out of hand. Civilization has its problems,

and even more distressing, there was indeed a kind of freedom in the

pre-industrial age that we can only dream of (but how rose-tinted are those dreams, discounting as they do death-in-childbirth, intestinal parasites, disease, disfigurement, starvation, slavery and so on? Just how far into the ‘escapism’ from reality should the Fantasy genre offer up? Oh, and that is the sixty-four dollar question I’m slowly approaching: the expectations of the fantasy readership, but everything in its time…). Accordingly, Karsa’s introduction into

civilization is one made in chains – in the stripping away of his ‘barbaric’ freedom. But arrogance is an unruly beast and he will not so easily be tamed, and so the struggle between barbarism and civilization becomes his own personal struggle (even Conan grumbled as much).

This then is a journey of prejudices under assault.

No wonder it makes so many people uncomfortable. We may not share Karsa’s prejudices, but we share prejudices. Because this is a fantasy novel and so incorporates adventure, this assault is personified with violence, and there is no need (for Karsa, anyway) to internalize it (Karsa is an outward character, not an inward character – and what you see is what you get and what you get is everything that he is, but that does not make him simple. In fact, he is probably the most complex character in the entire series, and in my recognition of that I saw that his tale could bear the weight of its own trilogy, and so it will).

We come at last to the expectation of the fantasy readership, and if you thought I walked a fine line with Karsa, wait till you read what follows. I am not just a writer of fantasy; I am a reader of fantasy, and so I can comfortably stand on both sides of this issue (as can all fantasy writers, barring those who claim to have never read fantasy, and those ones are either dissembling or they truly don’t have a clue). I have already broached the subject of escapism, but that is a universal

notion made up of numerous and at times contradictory desires, depending on who you talk to. So it needs elaborating.

One of the traditional appeals to epic fantasy literature of the ‘dark horde’ variety was its simplification of morality. There was clearly defined good and clearly defined evil. Good was good and evil was reprehensible. We were invited into a world where we knew who the good guys were, we knew who the bad guys were, and we knew that by the end the good guys would win, standing triumphant on the corpses of the bad guys (restless corpses were better, since that invited sequels). This is the child-like, play-ground appeal, and in appealing to the child in us it comforts by virtue of its simplicity; while at the same time its codifies the ‘good’ virtues and the ‘bad’ vices, which could in one sense serve as life-lessons. Accordingly, this kind of fantasy’s

engagement with reality was one of reduction, infused with exotic ‘otherness’ to stir the wonder of an imaginative mind. Comforting stuff, affirming stuff – in fact, the very stuff that Leo Grin applauds.

But that’s ‘epic’ fantasy. It’s not sword and sorcery fantasy: it’s not

R.E. Howard (arguably, it’s not JRR either, but I’ll skirt that particular can of worms here). Howard’s barbarian hero promised chaos and destruction – well, he promised to maintain his barbaric virtues even if it took the world down around him (lovingly spoofed in Jakes’ ‘Mention My Name in Atlantis’). And it if did, well, that was a civilized world, wasn’t it, so good riddance. The sword and sorcery form of fantasy literature twisted things, but something of that simplistic, reductionist sensibility still remained. Good was good (if a little hard) and evil was evil. Only the stigmata had changed. The ‘good’ was the purity of the Cimmerian ice fields; the evil was the steamy civilized southlands with their serpent gods and all the rest. It’s escapism of the nihilistic vengeance sort, the fascistic scouring away of corrupting forces (that part Leo liked, so doubt), with the Northern (white-skinned) Man standing triumphant, a freed and happily large-breasted ex-slave wrapped lovingly round one leg, on her knees of course).

Escapism is seductive, and what it might reveal about us is not always pleasant on reflection: it comes down to the flavours we prefer, the paths we find most inviting to our more fundamental belief systems – whether self-articulated or not, and that alone is enough to make any thinking person shiver.

Karsa is all of that stripped bare; and in turn he infuriates, shocks, and on occasion makes the jaw drop in disbelief. But he is also the reality of

the ‘barbaric’ and so represents an overt rejection of the romanticized,

fantasized barbarian trope. Some people don’t like that. Fair enough.

I come at last to my consideration of audience expectations. Believe me, I did consider them. I always consider them – but consideration does not guarantee a change of mind regarding the course I choose: more often, that consideration demands from me a challenge in exercising subtlety, and this is the nature of subversion as I work it into my novels (and series). Karsa subverts the ‘fantasy’ of the barbarian hero in Fantasy, and he does so because I feel that there is something dangerous in that romanticism, and in that vengeful refutation of civilization. In turn, however, Karsa’s tale also subverts the notion of civilization as virtuous savior and deliverer of enlightenment, because history tells us otherwise.

So I ended up punching both ways. It’s a damned wonder I didn’t lose

everyone after ‘House of Chains’ (or, more accurately, during the reading of ‘House of Chains.’). Structurally, I could not have introduced Karsa any earlier than I did. After three novels (all subversive in their own, unique ways) I was ready for something more overt – I was ready to take on the barbarian fantasy. At the same time,

an entire novel of that relentless point of view would have been one bridge too far. The struggle between barbarism and civilization is not just specific to Karsa or even his tale: it is the struggle within each of us, as we battle desires with propriety, and as we battle need with responsibility. In the remainder of the series, those battles are played out on grander scales. It could be argued that civilization’s greatest gift is compassion – the extension of empathy, even unto strangers, and as such acts in half-formed opposition to barbarism with its pragmatic viciousness, and if compassion must be our shield, it is against our own baser natures.

Karsa’s journey in this novel and in this series stand as stepping stones across this raging river of (invented) history. Later, he appears as a chorus in the ancient Greek sense, to remind us that we’re all playing with bones, not sticks and stones. To skip him is to miss a fundamental argument of this series: but then, as mentioned before, there are many forms of escapism, and the Fantasy genre speaks to them all at one time or another.

The Malazan series does not offer readers the escapism into any romantic notions of barbarism, or into a world of pure, white knight Good, and pure, black tyrant Evil. In fact, probably the boldest claim to escapist fantasy my series makes, is in offering up a world where we all have power, no matter our station, no matter our flaws and weaknesses – we all have power.

I don’t know about you, but I’ll escape into that world every chance I can.

Now, as Karsa would say: “Too many words. Witness.”

The above essay will appear on stevenerikson.com in the next few days. For those of who for whom life isn’t too short…

Cheers

SE

Well…

Not quite sure what to add after that but great to hear your thoughts behind your writing and as always one of the points I’ve most enjoyed about the series is the world building with Karsa’s and some of the other “primitive” cultures we see feeling real in a way few other writers have managed.

Thank you, Steven !

Spectacular !

…but…big BUT !: If you address Karsa in your essay, I think you should tackle his elliptic counterpart, too: Ublala Pung !

Wow, thanks a bunch Steve! very insightful and a great read. i think it posted the way you wanted. :)

but as polarizing as karsa has been, i think we can all agree that he is one of the most intriguing characters ever created, for all those reasons just listed.

I sometimes wonder how much of Ublala Pung’s best known moments are an affectation. He can’t possibly be that dumb.

I again give thanks for Steve being someone both capable of great and subtle writing and willing to tackle some truly evocative/provcative topics.

Defying a reader/viewer’s expectations is often a wonderful thing to come across and I’m lucky Erikson decided to do so much of it in the Malazan books.

Cheers, all.

Thanks Steve. Excellent insight into your thoughts on Karsa. That continued insight is a great part of what makes this reread so good.

Interesting stuff about Karsa.

I think for many readers, and since 99% of us read for “fun”, especially women, if I can generalize, seek a certain flux of empathy with what they read. Karsa, whether you like him or not, isn’t a character you can bond with.

For me, I read as long something is stimulating. A sympathetic character can be as interesting than one I end up hating. One aspect I liked was Karsa’s way of speaking. The complete lack of rhetoric or manipulation or hidden intent. So what I picked while reading “mimics” what Erikson described here, but taken from a slightly different perspective.

For me the contrast between barbarism/civilization was in the language (what Erikson explains as inward/outward character). Karsa’s language lacked the complexity of civilization, but also all its social traps and convoluted purposes.