In this bi-weekly series reviewing classic science fiction and fantasy books, Alan Brown looks at the front lines and frontiers of the field; books about soldiers and spacers, scientists and engineers, explorers and adventurers. Stories full of what Shakespeare used to refer to as “alarums and excursions”: battles, chases, clashes, and the stuff of excitement.

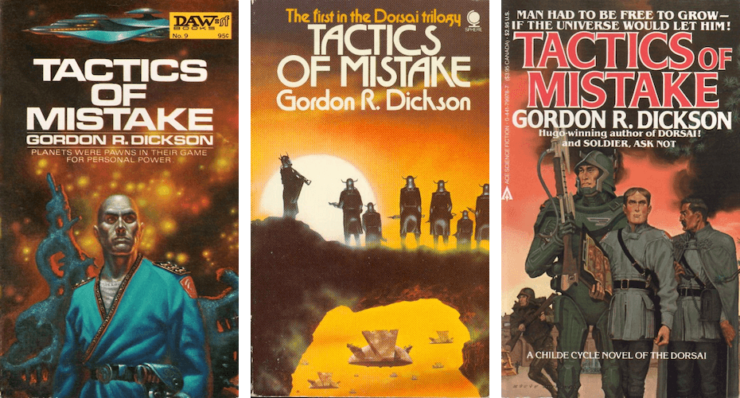

Today, we’re going to look at Gordon R. Dickson’s Tactics of Mistake, a seminal tale in his Childe Cycle series, focusing on his most famous creation, the Dorsai mercenaries. This book is full of action and adventure, but also full of musings on history, tactics and strategy, as well as a dollop of speculation on the evolution of human paranormal abilities. It is a quick read that gallops right along, with the scope of the story growing larger with every battle. Its protagonist, Colonel Cletus Grahame, is a fascinating creation, both compelling and infuriating—not only to the other characters in the book, but to the reader as well.

Imagine my surprise when I went to my first World Con and found the event guarded by an outfit called the Dorsai Irregulars. I had read about the Dorsai mercenaries in Galaxy and Analog, but never expected to see a version of them appear in real life. It turns out there had been problems at previous conventions due to regular security guards misunderstanding the culture of science fiction fandom. In 1974, author Robert Asprin created the Dorsai Irregulars, named in honor of Gordon Dickson’s preternaturally competent mercenary warriors (with Dickson’s permission, of course). And for decades, this uniformed, beret-wearing paramilitary group has provided security and support to many conventions. To me, their existence was a visible sign of the popularity and respect Dickson and his fictional creations garnered in the science fiction community.

About the Author

Gordon R. Dickson (1923-2001) was born in Canada but moved to Minnesota early in his life, and eventually became a U.S. citizen. After serving in the Army during World War II, he and Poul Anderson were members of the Minneapolis Fantasy Society, and the two occasionally collaborated on fiction, as well. Dickson published a story in a fanzine in 1942, but his first professional sale was a story co-written with Anderson in 1950. His short works were widely published in the 1950s and 1960s, covering a wide range of subjects. As mentioned above, his most famous creation was the Dorsai mercenaries, whose tales transcended the military science fiction genre with speculation on the future evolution of mankind. These stories were part of a larger story arc called the Childe Cycle, a project he was not able to complete during his lifetime. He wrote fantasy as well as science fiction, with his Dragon Knight novels about intelligent dragons being very popular. With Poul Anderson, he also wrote a series of humorous stories about teddy-bear-like aliens called Hokas.

By all accounts, Dickson was well liked by both peers and fans. He won three Hugo Awards during his career, in the short story, novelette, and novella categories, respectively. He won a Nebula Award in the novelette category. He served as President of the Science Fiction Writers of America from 1969 to 1971, and he was inducted into the Science Fiction Hall of Fame in the year 2000. While most of Dickson’s work remains under copyright, you can find one of his stories on Project Gutenberg.

Mercenary Warriors

Military adventures have long been a staple of science fiction, and for a helpful overview of the sub-genre, you can read an excellent article here in the online Science Fiction Encyclopedia. In the late 20th century, however, a new type of military fiction became popular: stories which featured a specific element of warfare—the mercenary. Mercenaries do not fight for love of any country; instead, they fight professionally for whoever hires them. I suspect this development had something to do with the inconclusive nature of the Cold War, the stalemate that ended the Korean War, and then the failures in the Viet Nam War, which created a sense of disillusionment among American military personnel and veterans. The entire Viet Nam experience created a sense of “What are we fighting for?” among the U.S. Armed Forces, especially after the release of the Pentagon Papers revealed both calculated deception and mismanagement of the war effort at the highest level. It is no surprise that fiction began turning to military characters who fought not for country or glory, but simply for pay, and for the people fighting alongside them.

Buy the Book

Network Effect

While there have been many stories featuring mercenaries since then, three writers stand out from the crowd. David Drake (see a review here) wrote stories of Hammer’s Slammers and other mercenary groups from the perspective of the front-line enlisted troops, focusing on the horrors of war. Jerry Pournelle (see a review here), in his tales of Falkenberg’s Legion, told stories that looked at the operational level of warfare, set in a rather grim future history that was strongly rooted in historical precedents. Gordon R. Dickson’s tales of the Dorsai did something else entirely. While there was plenty of action to keep things interesting, along with myriad examples of operational brilliance and grand strategy, it was clear that he had something grander in mind. He was looking to explore not just at warfare, but the nature of humanity itself, and the possibility of mankind evolving and transcending its previous limitations.

Dickson’s Childe Cycle, the larger narrative in which the Dorsai tales were set, looked at three different splinter cultures, each of which represented a different human archetype. The Dorsai personify warrior culture, the Exotics represent philosophers, and the Friendlies reflect faith and religious zealotry. While the Dorsai received more attention than the other archetypes and were certainly fan favorites, it is clear that Dickson was largely concerned with the overall evolution of superior mental, physical, and even paranormal abilities, and how this would shape humanity’s future.

The Dorsai novel Tactics of Mistake was first serialized in John Campbell’s Analog from October 1970 to January 1971. It is easy to see why it attracted attention from the editor, who had a fondness for both military action and explorations of paranormal abilities.

Tactics of Mistake

A Western Alliance lieutenant-colonel and Academy military history instructor, Cletus Grahame, apparently drunk, joins a table of dignitaries having dinner on an outbound space liner. The people around the table include Mondar, a representative from the Exotic colony on Bakhallan; Eachan Khan, a mercenary Colonel from the Dorsai world under contract to the Exotics; his daughter Melissa Khan; Dow deCastries, the Secretary of Outworld Affairs from the Coalition of Eastern Nations (who is obviously interested in Melissa); and Pater Ten, deCastries’ aide. The Coalition’s Neuland colony (backed by the Coalition) and the Exotic colony (backed by the Alliance) that share Bakhallan are arming themselves and seem headed toward war (the setting, with its great powers and proxy states, is very much rooted in the last century’s Cold War).

Grahame discusses laws of historical development, mentions a fencing gambit called the “tactics of mistake,” where a fencer makes a series of apparent mistakes to draw their opponent into overreaching, leaving them open to an attack, and brags that his ideas could quickly end a war between Neuland and the Exotics. Grahame then plays a shell game with cups and sugar cubes that he has rigged to make deCastries look foolish. This apparently random scene actually introduces almost all the major characters in the book, and sets in motion the conflicts that will engulf nearly all humanity’s colony worlds in warfare.

Grahame appears eccentric, but his Medal of Honor and wounds suffered during an act of heroism, which left him with a partially prosthetic knee, lend him some credibility. When the liner reaches Bakhallan, he, Mondar, Colonel Khan, and Melissa are in a car heading toward the capitol where they are attacked by guerillas, and only decisive action by Khan and Grahame foils the attack. Grahame reports to General Traynor, who has been ordered to take Grahame’s advice, but barely tolerates his presence. Grahame warns of an impending incursion by Neuland troops through a mountain gap, eager to impress their patron deCastries. The General scorns his advice, but gives him a company of troops to defend the gap. Grahame takes that company, whose commander also resists his advice, and it turns out he is right in every one of his predictions—through his personal heroism, the Alliance is able to turn back the attack. Grahame ends up in the hospital, having further damaged his wounded knee. Grahame and his insistence that he is always right impresses some but alienates others…especially when it turns out that he is correct.

Once Grahame heals, he befriends an Alliance Navy officer who has giant underwater channel-clearing bulldozers at his disposal. With Colonel Khan’s approval, he takes Melissa on a date that turns out to be an underwater journey up the river, where, just as he predicted, they encounter and interdict a major incursion effort by the Neulander guerillas, capturing the entire flotilla. Melissa is impressed, but then Grahame infuriates her by talking about how deCastries is becoming obsessed with beating him, and then tells her what he expects her to do.

Then Grahame, convinced that another attack through the mountain gap is coming (this time with regular troops), convinces the General to give him a small group of Dorsai troops and the freedom to deploy them as he wishes. Sure enough, the attack occurs just as he predicted, and to keep the General from interfering, Grahame asks him to come to his office, which has been booby trapped to keep the General in so that he cannot countermand any of Grahame’s orders. With clever deployment of his limited troops and use of those Navy underwater dozers to cause convenient river flooding, the bulk of the Neulander regular army is captured. Grahame again pushes himself beyond his physical limits, to the point where doctors want to amputate his leg. The furious General finally escapes, only to find that Grahame has already resigned his commission and been accepted as a new citizen of the Dorsai world.

And at this point, having spun a tale that is already satisfying in itself, Dickson’s larger ambitions become clearer. There have been hints throughout the narrative that Grahame has innate abilities similar to those the Exotics work to develop—abilities that help him predict the actions of others, and the consequences of various alternative courses of action. He summons Mondar for assistance in an effort to regrow a new and healthy knee: an effort that not only succeeds, but helps Grahame develop control over his body, giving him superior strength and endurance. The defeated deCastries visits Grahame, who predicts they will meet again in battle, with deCastries leading combined Alliance/Coalition forces and Grahame leading forces from the colony worlds, who will be colonies no more. Grahame creates a program to allow the Dorsai to develop their own superior physical abilities. The rest of the book follows a series of campaigns where the Dorsai become virtual super-soldiers, individually and collectively superior to any army ever assembled. Along the way, the seemingly cold Grahame continues to either infuriate or delight those around him, absorbed in military matters to the point of obsession; he also has a relationship with Melissa which is alternately chilling and heartwarming. Tactics of Mistake is a relatively short novel by today’s standards; in order to cover all this ground, the narrative zips along at a lightning pace that grows ever more rapid as it builds to its conclusion.

Final Thoughts

Gordon Dickson was one of the great authors of science fiction in the post-WWII era, and had a long and productive career. His Dorsai were fan favorites, and he wrote many other popular books, full of adventure and philosophy in equal measures. There have been few writers as ambitious as he, and even fewer who achieved what he was able to accomplish. Tactics of Mistake is a strong example of his Dorsai tales, and while some of the attitudes are dated, it is a fast-paced tale that is well worth reading.

And since I’m done talking, it’s your turn to chime in with your thoughts on Tactics of Mistake and any other example of Gordon Dickson’s work. One of my favorite parts of writing this column is reading your responses, so I look forward to hearing from you.

Alan Brown has been a science fiction fan for over five decades, especially fiction that deals with science, military matters, exploration and adventure.

You’ll also find hints of Liddell-Hart’s popularization of the Indirect Approach in Dickson’s works on the Dorsai. This was a good book, one of the better ones in that series but to my mind, the best was “Lost Dorsai”.

I reread the core Dorsai for the SFBC in ages past [1] and was struck by how Grahame’s enemies seemed by and large to be idiots. Also, that even when I was a feckless teen, the romance was pretty unconvincing.

1: As I recall, I guessed correctly that they were going to be the next books assigned to me, so I reread and reviewed all four, then fired off the reports before getting the formal assignment. Turned out submitting replies in negative time was not considered a plus.

In my opinion, Dickson didn’t really come into his own until 1964 with Soldier, Ask Not. Prior to that, he showed occasional flashes of what he would be, but largely suffered from pulp tropes and weak humor (like his Tom and Lucy Reasoner stories). Personally, I think it was writing so much for Analog that held him back. Campbell had very specific ideas and tastes, and by the late 50s he had pretty much ossified. You can see his best stuff is in magazines edited by Fred Pohl, decent stuff when edited by Cele Goldsmith Lalli, and the Campbell stuff all reads like it was written in the 50s or even earlier.

I’ve not read much by Gordon R. Dickson. I’ve read one Dorsai novel that I wasn’t overly fond of, and a different space opera novel I wasn’t fond of, but I really liked his short story collection Mutants and his novel Outposter. Which just goes to show that there’s usually something for everyone if you keep looking.

Mutants had a Dorsai short story in it which was impressive (“Warrior”) but I preferred his terra uber alles short story “Danger-Human!” and his elegiac short story about humans and dogs “By New Hearth Fires” (one of my favorites of all short stories).

Ouposter was an interesting way of presenting a novel in which the events which shape the hero are all in the past and what we see is a novel in which the hero’s final plan is going into effect. It’s rather like the third book of a trilogy in which we never see book one which has him learning to be an Outposter, or book two which has him as an Outposter living on Earth and seeing it for what it is. But it’s entertaining as heck to watch the hero operate at such a high level, knowing the cost for what he’s doing and being willing to pay it anyway.

@1 It is obvious Dickson read his military history and philosophy, and favored the kind of warfare envisioned by Liddell Hart. This tale was very much shaped by the counter-insurgency theories of its time, with lots of emphasis on maneuver and surprise (the type of tactics we now call asymmetrical).

@2 Yes, the contrast between Grahame’s skills and those of his opponents was exaggerated a bit too much. And the “romance” was sexist and clunky enough to set my teeth on edge.

@3 I haven’t read enough of Dickson’s work to see the editorial influence, but I have seen it with other authors. If you weren’t willing to write a Campbell story, you weren’t going to sell it to Analog. As a youngster, I didn’t appreciate Pohl’s skills as an editor. Looking back, I think he was, and still is, very much under-rated compared to the influence he had on the field.

Is it possible that the increasing popularity of stories about mercenaries in late 20th-Century SF might also have had something to do with the greater popularity of libertarianism during that period?

It doesn’t come up in Tactics because the various social factions are still gelling but something I wondered in the later Dorsai books is who the hell hires the Friendlies? Who looks around and says “Humourless religious fanatics whose primary role seems to be to provide the Dorsai with asses to kick? Those are the guys I want to hire!”

@6: Considering that one of the major underpinnings of libertarianism is a non-interventionist foreign policy, I’m not sure how that follows. Just because mercenaries aren’t employees of the government doesn’t mean that they aren’t intervening in some foreign country.

@7: I remember few details, but retain a strong impression that their main virtue was low cost, and generally being sufficient if you weren’t going to go up against professionals.

The point about them that always struck me was that humanity was splitting into three splinter cultures, and *two* of them were paying the bills as mercenaries?

@8 – I was thinking of the free-market aspect of mercenary groups.

@9: There’s a 4th splinter omitted from this review but mentioned briefly in the story. The science culture of the Newton colony. There’s a bit of the planetary monoculture problem, for sure–especially in the implied unity of all of Earth against the various colonies. Yes, he mentions a world gov, but even in this early novel the earth characters are painted with broad cultural strokes.

I always thought the battles in the Childe cycle novels surprisingly bloodless–more maneuvering and trickery than slug-fests. I presumed Dickson did that deliberately, and wondered if some part of his personal background led him that way.

I agree that the romance barely deserves the name–it’s as though it were lifted from some 30’s-era pulp novel.

At least some of his great popularity with fans was that he was an extremely social writer until his health declined.

He was often found at convention parties at all hours of the night and sometimes attended the local science fiction group (Minnstf), This partying is memorialized in the filksong “Gordy Dickson” He’s the one.

I have fond memories of him playing Ben Bova in the early Minicon production of “Midwestside Story” (Bova was GOH that year).

I wonder if all I see in Melissa is really there or projection on my part? Melissa Khan is a woman with a purpose, to get back the position Earth expat Eachan Khan lost when his country was absorbed by the super states back when she was a child. She has been so committed to this idea for so long that she’s failed to notice Eachan has totally moved on. Melissa has an unusual gift, possibly a form of empathy, she intuitively knows what people are feeling though she doesn’t always interpret her input correctly. She thinks she’s made a good start on achieving her goal by charming Dow de Castries. Her attraction for Cletus is a most unwelcome distraction. It gets worse when Cletus reveals himself as having an agenda of his own and to want her father for it. Melissa’s problem; does she give up her own plans and throw in with Cletus? Does he actually care about her and Eachan? Can she trust him with her father’s future? She has to be careful because a misstep on her part could put the men at each other’s throats.

Cletus uses that concern to force her to go through with their wedding. He thinks he’s got her trapped. He assures her that it will be a marriage in name only and in a few years when his plan is completed she can get a divorce and take Eachan wherever she likes. Melissa asks if he ever loved her? He evades, ‘Did I ever say I did?’ and leaves the room fast.

Melissa now knows Cletus loves her. She also knows that he’s miscalculated. She can in fact take Eachan and go anytime she wants to. She decides not to. Cletus, being an idiot fails to understand she’s chosen him even after she consummates their marriage and bears him a son. Brilliant logician but rubbish at understanding emotional logic.

@11,

Quite a few historical mercenary battles were jockeying for position and ended before a shot was fired. Dying or, worse, being injured would damage one’s earning potential, plus the gear might get damaged. This didn’t always happen, and wouldn’t when government forces were involved.

———

I liked the Childe Cycle of stories when I read them and still think them better than much of today’s military SF, possibly because some later milSF doesn’t seem to think there is a valid human society outside of the author’s protagonists.

@13 It was a nice twist to see that, brilliant as he was on the battlefield, Cletus was totally outmatched by Melissa. I just hated to see him so dismissive of her.

@14 Mercenaries have always loved bloodless conflicts decided by maneuver. In fact, most conflicts start with attempts to win by maneuver, and “get the boys home by Christmas.” But things get messy when that almost inevitably fails. The problem with clever maneuver warfare is, to paraphrase Clausewitz, “in warfare, even the simplest things are difficult.” In fact, Cletus’ superpower is the fact that all his plans survive contact with the enemy.

Of course, a second issue with mercenaries is that they will occasionally note that there’s more money to be made by taking over the government that’s employing them.

I was a big fan of Dickson in the 70’s and 80’s. I haven’t re-read him so I don’t know what I would think of them now but I followed the Childe Cycle from “The Genetic General” (or DORSAI!) through YOUNG BLEYS. I found them fascinating in many ways. My favorite thing about them and the reason I kept reading was the growth of Dickson as a writer and the deeper insights of important themes as he was able to write more of what he wanted to write. He is not well known among modern readers because he did start out rather “pulpy” and a “John W. Campbell writer” which does not work for younger readers. But his later novels are rich with thought and fascinating. He wrote other books that I liked as well – especially TIME STORM and THE FAR CALL but again they may be too out of date now.

Tactics of Mistake has pretty much the same plot as Dorsai!, as I describe here.