If you’ve heard anything about Heretic it’s probably that it’s another great villain turn from Hugh Grant, and I’m pleased to report that his performance surpasses the hype. While, alas, there is no song-and-dance number, he’s even better here than in Paddington 2. All of the bumbling, stammering, and twinkling that made him such a charming romcom star now curdles into a performance designed to fool young women into feeling safe so he can get them where he wants them. But the movie is more than just a star turn for Grant as the nefarious Mr. Reed; Sophie Thatcher (Sister Barnes) and Chloe East (Sister Paxton) match him in every scene, the mood and design are creepy and perfect, some of the twists are great, and, best of all, this movie is stuffed with ideas.

They don’t all work, at least for me, but what a blessed relief to spend two hours with a movie that wants you to think.

Sister Barnes and Sister Paxton are a pair of young Mormon women in their mission era. An explanation for the un-initiated: In The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, young people are encouraged to spend two years (for men) or 18 months (for women) volunteering as missionaries. They go out in pairs or small groups, visiting houses and speaking to people on the street about Mormonism, working to get sit-down discussions with people who are interested in converting. They have to live by strict rules and dress codes while they do this, including the one that becomes a plot point in Heretic, which is that missionaries aren’t supposed to be alone with a potential convert of the opposite gender unless they have a chaperone. The movie joins Sisters Barnes and Paxton as they walk through the town they’ve been assigned (I think it’s in Colorado), trying and failing to speak to people. After a long and fruitless day of work, the Sisters end up at the large rambling house of one Mr. Reed, who has contacted their homebase church about a visit. In other words, he’s invited them to come, and has expressed interest in the Church. After their shitty day, the two are hoping this means he’ll really listen to them, and maybe even consider more visits. Sister Barnes, the older and more experienced of the two women, is hoping that the more naive Sister Paxton will finally net her first conversion. When Mr. Reed eventually opens the door (just as the driving rain outside turns to sleet), he cranks the befuddled charm up to 11, insists that his wife is just out of sight making a pie and will join them in a moment, and ushers the two Sisters in for their chat.

This is not a typical horror movie, or even thriller. Yes, the women stumble into an uncanny world and realize their mistake too late, and yes, they’re kind of in a cat-and-mouse game with a captor who holds all the power—but the thing that makes Heretic fun is that most of the action is conversation. Sisters Barnes and Paxton have come to the house ready for a debate. Mr. Reed reached out to the church and said he was interested in learning more about the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints, so they’re expecting to sit and speak with him, for a long time, about their faith. They’re seeing this as, possibly, the first of several conversations, that will hopefully end with him choosing to convert. The movie stays true to this, and allows the conversations between the Sisters and Mr. Reed to play out exactly the way they would in real life—lulls, pauses, awkward jokes, rote recitation, argument, moments when Mr. Reed seems to defeat one of their points, and moments when they pull the conversation back their way. It takes its time making Mr. Reed more and more argumentative. Gradually, Mr. Reed transforms into a smarmy, condescending, cruel man, who slams a copy of The Book of Mormon down, bristling with tabs and annotations, challenges them on polygamy, and needles them about obscure decisions their church made a century and a half before they were born.

And where the heck is this alleged wife, anyway?

Obviously, a horror movie that’s also a two-hour long theological debate is not going to be everyone’s slice of blueberry pie, but I loved it.

Now you might ask yourself: If Mr. Reed is going to be so cantankerous about Mormonism, why did he invite two missionaries into his home to discuss it? It turns out that he’s obsessed with the concept of iteration. According to Mr. Reed, many things that are popular in the 2020s—songs, games, even religions—are actually echoes of earlier things, and if you pay attention, and pick the current stuff apart, you can trace original ideas back to their sources. Putting this into practice with a song, he plays them the Hollies’ 1974 song “The Air That I Breathe”, and when they insist they’ve never heard it, he explains that they actually have because surely they’ve heard Radiohead’s “Creep”, or more recently, Lana Del Rey’s “Get Free”, both of which came under legal scrutiny for using the song’s melody and chord progression—the Radiohead song from the Hollies’ publisher, and Lana Del Rey’s from, hilariously, Radiohead themselves. He also walks them through another example in the gaming world that is both hilarious, and a fun meta commentary on the misogyny that echoes through the whole film.

That’s all fine, but then he also applies it to religion. What is Mormonism if not the latest riff on Christianity persevering? And what is Christianity of not a riff on Judaism? If Judaism is the “source” text, shouldn’t it offer the most direct experience of God? In which case why wouldn’t everyone who wants to have a relationship with God just be Jewish? What is even the point of you, Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints? And then Mr. Reed goes a step further. Christians want to believe that Jesus is the messiah, the savior, the Only Begotten, etc.—but what about all those other savior figures, born of virgin mothers, amassing followings, and then dying and resurrecting in stories told across ancient Egypt, Sumeria, Greece, and so many others? Dare I ask: What would Osiris do?

The Sisters, who were a little baffled but intrigued by the music and gaming examples, push back when Mr. Reed applies his iteration theory to religion. Sister Barnes points out that Islam doesn’t fit into his narrative at all, and also that one of the messianic figures has a “freaking bird head”, which sets him slightly apart from the most likely human-headed Jesus. But what’s more important is that Mr. Reed is trying to get them to accept that with all these stories flailing around, the only possible truth is meaninglessness (terrifying though that may be); it’s fascinating to watch Sister Barnes push back on that, while Sister Paxton tries her best to be unfailingly polite to Mr. Reed, even though she’s scared to death of him.

And that brings me to maybe my favorite aspect of the movie, which is its ultimate respect for Mormonism. Mormonism tends to be a pop cultural punching bag, with outsiders focusing on the plural marriage, the “magic underwear”, the oeuvre of Matt Stone and Trey Smith, Angels in America, the soaking, the wacky afterlife, the denomination’s extremist fundamentalist arms. (As though every religion and denomination doesn’t have its own wacky afterlife, or extremist fundamentalist arms?) Anyone who’s in a slack or group chat with me knows that I too have gently dinged the church from time to time, and I’ll cop to it: I make fun of the caffeine prohibition, because I am addicted to caffeine and the idea of living without it genuinely frightens me; I make fun of the earnestness, because I am creature of irony, and true earnestness drives me up the fucking wall. Naturally earnestness is Heretic‘s secret weapon.

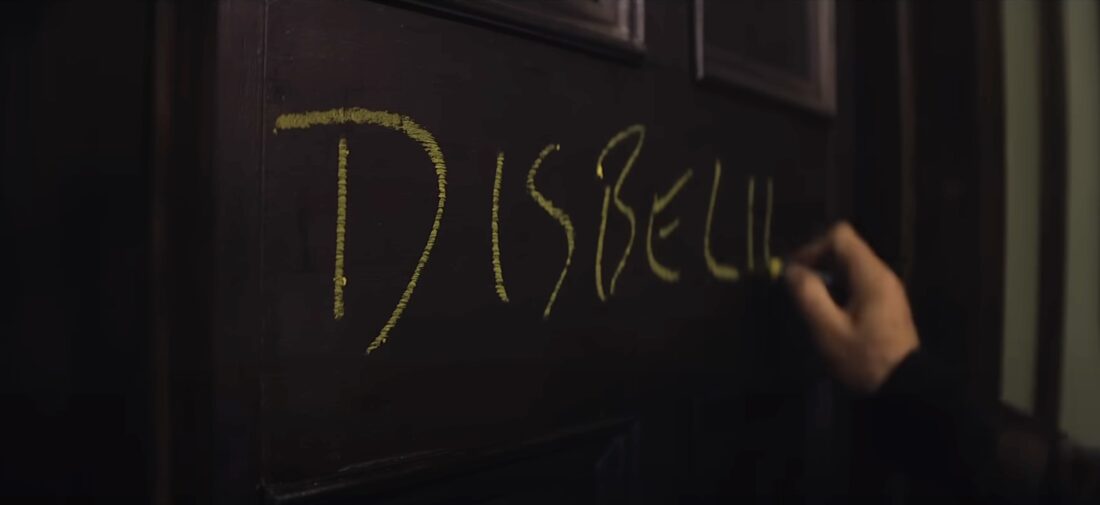

At one point, after the women have realized that they’ve stumbled into a horror movie, Mr. Reed gives them a choice. If they want to leave they can go through a door marked “Belief” or the one marked “Disbelief”—but they have to choose, they can’t go back out the way they came in. He’s trying to tell them that their lives are different now, they are not who they were when they turned up at his front door. But of course, this is Mr. Reed deciding for them that their lives are different, and that this conversation-turned-lecture on religious history has rewritten their brains, just as his research on religious history rewrote his.

I am reminded of a New Testament class I took once, approximately a billion years ago, at a college that no longer exists. After an entire semester of picking apart the Gospels and Letters and archaeological finds and pumpernickel-dense German theology, on the very last day of class, a student put his hand up and asked the professor, “But can’t we prove any of the miracles?”

The second half of the movie is about how they respond to Mr. Reed’s attempt to control their narrative and force his idea of “truth” on them, but saying much more will spoil the whole thing. The twists pile up, some more successful than others, until the film hits an ending that can be interpreted in a bunch of different ways that may or may not pay off the masterfully tense first hour. I think it worked for me more than it didn’t. I don’t do binaries, but especially this week I appreciate a movie that sets an older man who loves control and humiliation against a pair of young women who use cooperation and love to fight him.

One final note, that doesn’t have anything to do with the plot of the movie: from a certain point of view, the single best moment in Heretic happens during the credits. I’m not saying that to disparage the movie, which, as I’ve said, I enjoyed immensely, but the line in question is a simple line of text that says “No generative AI was used in the making of this film.”

Could this become a gauntlet, please? An incredibly low bar that other filmmakers are encouraged to clear? It’s possible—likely—that talking about art and culture, and holding standards for that art and culture, is going to become even more difficult in the months and years ahead. (It’s already been difficult, as the screams of “just let people enjoy things!” and “how much did you shills get paid for this” have become louder and louder.) Using generative AI is not skilled labor. AI can’t do what I do, any more than a computer can program itself, or a robot can really clean your home or teach your children. I mention all of this because Heretic is fun and inventive and mostly a great time at the movies, and it was made entirely by people, and call me crazy but I think human art should be made by humans. I think more filmmakers should make it clear that it’s all their own work, and i think we should hold the line against letting machines do a piss poor job of something that has given life meaning for thousands of years.