When it comes to space movies, it seems like moviemakers have a choice to make: is this story a work of competency porn? Or is it a Haunting Meditation on Time and Grief and Possibly Dad?

The Right Stuff, Apollo 13, and The Martian march enthusiastically down the first path. Scientists and engineers scribble out equations and use slide rules to apply Newtonian physics to a problem, and astronauts deal with the cold reality of space. There’s a lot of gallows humor, and the only musing is maybe on America As an Idea.

First Man, Ad Astra, and The Midnight Sky put that nerd shit in the background to deal with GRIEF and/or DAD STUFF. Space may be real, but it’s also a metaphor for the unknowability of existence.

Then you’ve got your Gravitys and Interstellars, that act like the first one, but turn out to actually be the other one once the plot kicks in. (Although to be fair, Gravity at least adds MOM STUFF to the equation.)

I love both of these types of films (First Man was one of the most haunting movie experiences I’ve ever had, but I can literally watch Apollo 13 and The Martian once a week and be fine with it) but all of this is to say I came into Spaceman with a lot of other Space Movies in my head.

Spaceman sticks to the second path. If you saw it pop up on the Netflix menu and thought you’d tune in for Adam Sandler in a wacky space misadventure, this is not that. If you thought it was a technical exploration of a near-future or AU Czech space program, it’s also not that. This is a quiet movie about relationships, with a little world history folded in, spiked occasionally with humor and uncanniness. It doesn’t always work, but while I don’t think it’s entirely successful as an adaptation, it’s an interesting addition to the Space Feelings subgenre.

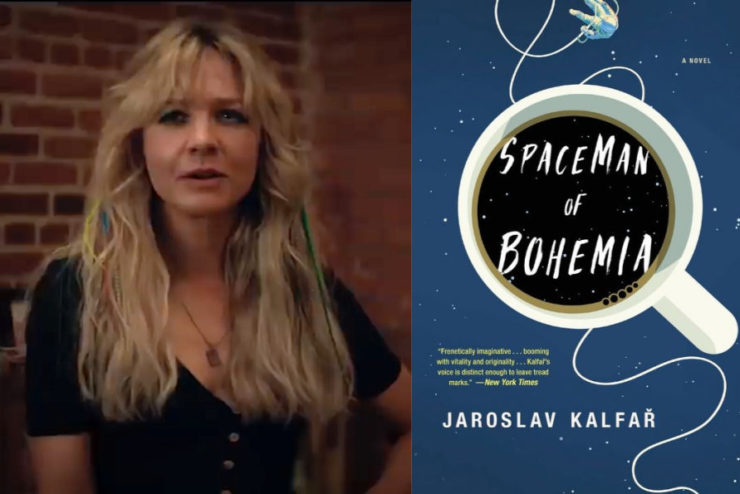

Spaceman is based on Jaroslav Kalfar’s 2017 novel The Spaceman of Bohemia, which I had the joy of reviewing. It was written for the screen by Colby Day and directed by Johan Renck, late of Chernobyl. Parts of the film work well, but I think the book is richer in many ways, and I hope that, whether you like the film or not, you’ll check the book out. As usual, I’ll give a spoiler-free overview first, and warn you when there will be light spoilers further down.

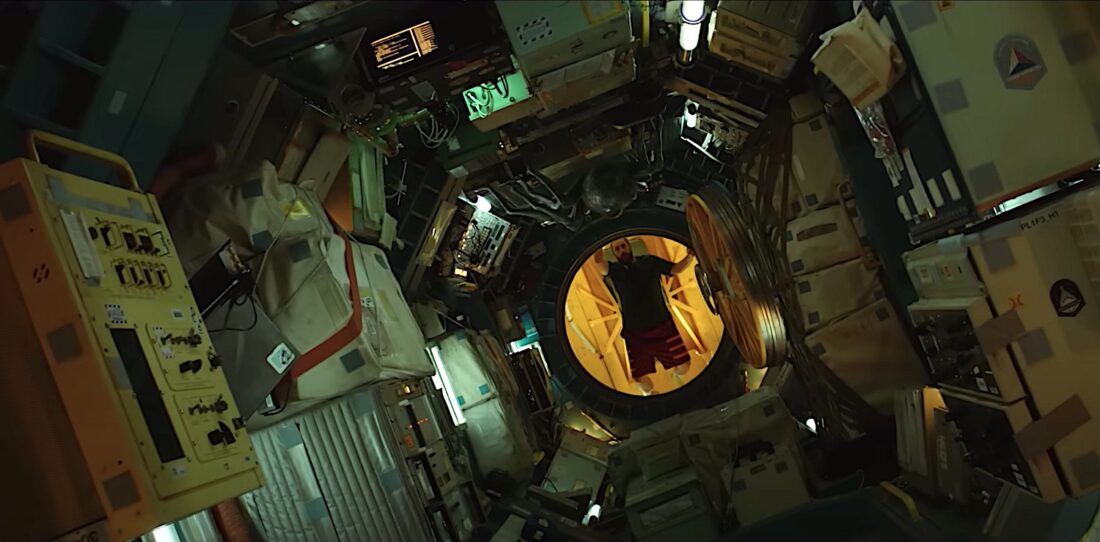

The main plot of the film is thus: There is an Interstellar Cloud called Chopra hanging out just beyond Jupiter and tinting Earth’s sky purple. In either a near-future or alt-universe Czech Republic, the government has teamed up with various corporations to fund an exploratory mission. If their chosen Cosmonaut, Jakub Procházka, can beat the South Koreans to the Chopra, all glory and fame will go to the Czechs. The only problem is that Jakub (Adam Sandler in sad quiet mode) is being slowly chipped away by the isolation of space, troubled by memories of his Communist father, and even more troubled by the collapse of his marriage to Lenka (Carey Mulligan), his luminous, and very very pregnant wife. Will he make it to Chopra? Will he and Lenka work stuff out? Is the GIANT SPACE SPIDER (voiced perfectly by Paul Dano) who shows up on his ship real, or a hallucination? Spaceman spends more time on the last question than the others, and mines some great comedy and a fair bit of eldritch horror from the Jakub’s reluctant partnership with the many-legged alien creature he calls Hanuš.

Having said that, I’ll dive into a bit more the plot now—jettison yourself from the airlock if need be!

Much of Kalfar’s novel focuses on Czech history, and the upheavals that communism brought to the Procházka family, and how the Velvet Revolution of 1989 affected it. This is cut down in the film, with a simplified thread about Jakub’s relationship with his true-believer communist father, and much more emphasis on how those emotions are affecting his relationship with Lenka. Lenka is often more of a symbol than a person—sometimes literally, as she and Jakub meet when she’s dressed as a Rusalka—but that’s part of the point, as Jakub gets lost in memories of her and thinks of her as a fixed point to get home to.

Fortunately, the film also gives us a few scenes of Lenka living her own life back on Earth, but I’ll come back to those in a moment.

The reason Jakub is able to fall into hallucinatory memories? He’s kind of stuck in a mind-meld with a giant space spider. The spider turns up when Jakub is a particularly low emotional point. He’s an alien who fled from his home planet, and he thinks human are interesting. He appears in the ship, subjects Jakub to a series of intense conversations/therapy sessions, looks into his mind to understand him, and samples his food. Is he real? Is he a product of Jakub’s loneliness? I didn’t care in the book because I loved him too much, and here I don’t care because the film gives him heft and weight, and a fantastic voice provided by Paul Dano. He and Sandler make for a solid odd couple—but more than that, the arc of their relationship really comes together by the film’s end, I think. I’ll come back to that, too.

Lenka’s sections on Earth are gauzy, meditative. One of my complaints about the film is here, but first I’ll tell you what worked: Lenka has a muted standoff with the head of the Czech space program, Commissioner Tuma, played by Isabella Rossellini. Rossellini is so good, so real and true in this scene that could have felt either like throwaway connective plot tissue, or like a stereotypical “person in authority tries to bully a civilian” scene—my least favorite type of scene. The other aspect that’s great is that Lenka’s mother is played by Lena Olin, who played Sabina in Philip Kauffman’s 1988 adaptation of Milan Kundera’s classic The Unbearable Lightness of Being, which you should watch if you haven’t. I never thought I’d get to say: “nice callback of Czech classic casting!” but now I do. And of course, Olin is perfect in the role… which brings me to my complaint. I wanted a lot more of Earth.

In the book, the reader is almost entirely, or maybe entirely, in Jakub’s experience, mind, and memories. He’s alone in space for large parts of the plot, and when he does have company it’s a giant spider he might be hallucinating, so there are many pages of philosophical meditation, musings on Czech history, and excavated memories. And that works really well for the book. But for the film adaptation I wanted to see more of the near-future society that sent him into space. I wanted to see what the purple-tinted Chopra cloud was doing to human consciousness. And wanted much more of Lenka’s struggle with being the person left behind, dealing with being very famous and basically almost powerless. Once again Carey Mulligan is stuck in a relationship with a troubled man who finds a greater emotional attachment with someone else: unlike in Maestro, here it’s a sentient space spider, and once again I wanted to spend more time with her as an individual person, rather than half of a couple.

One of the highlights of the film is how much Czech stuff they’ve carried over from the book. (Czechtches?) As I mentioned, when Jakub meets Lenka she’s dressed as a Rusalka, a Slavic water sprite, and Czech composer Antonín Dvořák’s opera Rusalka plays in the film. The communication system the pair use to speak to each other is called CzechConnect. Jakub’s ship is still named the Jan Hus 1—Jan Hus being a Bohemian religious reformer whose ideas were a precursor to what later became Protestantism. And Hanuš is still named Hanuš after the possibly-folkloric clockmaker of Prague. Best of all, Hanuš and Jakub bond over the greatness of chocolate-hazelnut spread.

I’m so glad they allowed Jakub to be as shitty and self-centered as he is. They don’t sugarcoat the fact that he’s acted terribly, but they also allow him to be human and loveable despite it—or maybe because of it. Sandler imbues Jakub with so many layers of insecurity, fear, and ambition that we can see why Lenka fell in love with, and why he’s driven her away.

I also want to mention as an aside: yes, there are similarities to Project Hail Mary. Kalfar’s novel came out in 2017, and Spaceman is solidly based on that, not Weir’s book. But it’s a fascinating exercise to look at how two very different writers use an idea of first contact—I might just have to essay the heck out of it later.

Now I know I shoved people out of the airlock for spoilers a few paragraphs ago, but I’m checking in again now: I’m about to talk about the ending. Definitely get outta here if you haven’t seen the film, but you’ve been reading along anyway and don’t want to know how the movie ends.

Jakub’s rift with Hanuš is really, really upsetting. I’ve read the book and I was still surprised at how upset I was! If a giant space spider ever locks its eight eyes on me and says: “My interest in you has expired,” I will walk into the sea. Or space, whichever’s closest. So naturally when they come back together, and Hanuš reveals that he’s dying, and doesn’t want to face that alone, it wrecked me even more than I expected. Because it isn’t quite that he’s changed his mind about Jakub, it’s more that he’s incredibly lonely, and still trying to help his new human friend despite everything. As they reach Chopra, Hanuš tells Jakub that it’s “The Beginning”. The cloud is made up of particles from the beginning of the universe. (“In the beginning was bi lighting” is an encouraging thought for some of us, so thanks for that, movie.)

The movie is a more straightforward experience than the novel, and the filmmakers made two choices for the ending that, weirdly enough, mirror the two paths for the subgenre I mentioned above. When you’re ending your space movie, I think you have to choose between reality and metaphysics. Either the engineers and the astronauts solve the problems and survive the voyage or they don’t, OR, you get into Star Baby/The Alien Is Her Father territory. (Or you end on a vague note of gooey hope wrapped in harsh reality, as in perpetual outlier Interstellar.)

Spaceman creates a different path in order to have it both ways. As Jakub collects Chopra particles to take home to Prague, Hanuš leaves the ship. (Hanuš has been able to phase through the ship at will, one of the points toward him being a hallucination.) Jakub has to make a choice in that moment between continuing his glorious mission or following his friend. The film nods to reality by having Jakub in his spacesuit, but from there? Hanuš is somehow able to float through space, to hold and carry Jakub, and to usher him into a swirling CGI Beginning full of stars… and decades of Jakub’s memories, and his acceptance of the idea that Lenka is the most important part of his life, but he might never get back to her.

If the film only did this, I’d still consider it a decent adaptation. But it takes another step. Hanuš told Jakub that he was infected with parasites called Gorompeds, and now we, and Jakub, see what that means: the tiny maggoty creatures swarm from Hanuš’s pores, devouring him before our horrified eyes. This is not a peaceful death, a merging with The Beginning, or an ancient Hanuš transformed into a Star Spider Baby: it’s life devouring life. End/Beginning.

Rather than tipping entirely into metaphysics, the film gives us time to contemplate the wonder of The Beginning—and then yanks us back to the reality of Jakub in space, the mission, the South Korean ship gliding into view, Lenka and a new life waiting back on Earth.

While I don’t think the film worked all the time, and I wish there’d been room for more Czech Stuff and more Lenka, Spaceman is still a compelling work of Space Meditation, and I want the entire universe from Beginning to End for Hanuš.