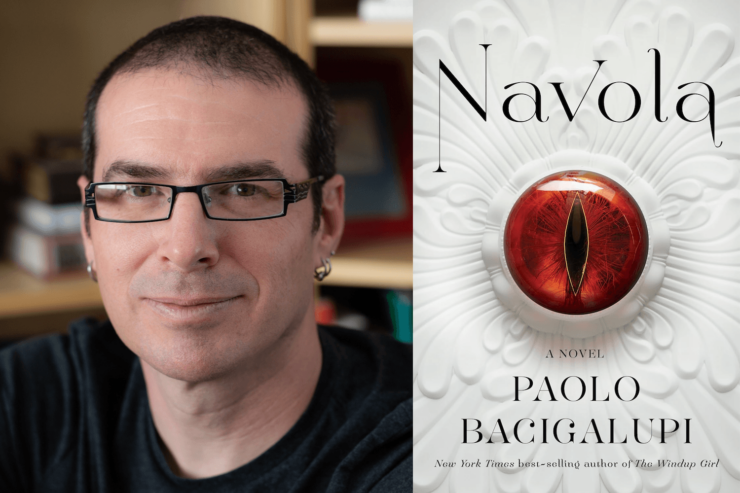

Paolo Bacigalupi is a multi award-winning American writer, whose first novel The WindUp Girl won the Nebula, Locus and Hugo awards in 2010. He is also the author of the Ship Breaker YA trilogy. His latest novel is Navola, a grand historical fantasy about political intrigues, power plays and myth. Over email, Paolo answered a few questions about his new book.

Mahvesh Murad: I think we can safely assume that it was climate fiction that you were mostly known for, which of course Navola is not. Was there pressure to keep writing the same genre, along the same themes? What made you switch gears at this particular juncture in your career?

Paolo Bacigalupi: There wasn’t pressure, exactly, but when you build a pattern of writing in a particular way, even you expect yourself to continue in that vein. At some point, it just became unsustainable for me. It wasn’t healthy for me to both be anxious about our future in my regular life, and then also carry those fears into my creative life, where I was extrapolating forward into horribly broken and dysfunctional futures. That’s not a sustainable way to be, if you don’t have some way to let off the pressure. Writing Navola was that pressure release. Something that was simply pleasurable to create.

MM: Navola is set in Renaissance Italy, and is about a fictional merchant banking family. Was the House of Medici’s an inspiration for the di Regulai? Did your interest begin with that time period in history, or with that area?

PB: My friend Daniel Abraham gave me a book years ago called Medici Money. It got me interested in both merchant banking and innovations in how money was used and represented and then also in the period of the Renaissance. When I started creating Navola those ideas were already in the back of my mind, and they seemed to fit, so I went with them.

MM: Navola’s opening line is ‘My father kept a dragon eye upon his desk’—was this the seed for this entire story, this entire world? Did Davico then come along, and did his personal story come to you as a whole, or in pieces?

PB: That sentence launched the story for me. I don’t know where it came from, or why I wrote it, but it launched my exploration into Navola. Almost immediately both Davico, with his kindness and innocence, and his father Devonaci, the shrewd manipulator of power, appeared on the page as well. From there, it was a bit of an exploration. I didn’t know the whole arc, right from the start. That was a found object. Much like the dragon eye, I suppose. I wasn’t actually intending to write a novel when I started. In fact, I was so burned out from writing, I wasn’t even sure I still wanted to be a writer. So I took my time and let the story unfold however it wanted, mostly just as an excuse to explore the world that seemed to almost be building itself as I wrote, with its myths and philosophies and languages and poems and songs and characters.

MM: This is a novel with GIRTH—the worldbuilding, the lore, the dramatis personae, all quite extensive, and all quite different from anything you’ve written before. Was it fun meeting new people in this new world? New to us, new to your previous creations too.

PB: Yeah, this story just kept growing. The reason it became so large was because I was having so much fun with it. I liked the people who appeared on the page, I liked all their plots and personalities, the venal and noble, the innocent and the corrupt. They all delighted me.

MM: Navola’s world is, to a great extent, a world very familiar to ours on the surface of it—it’s recognisably Renaissance Italy. You’ve used a smattering of faux-Italian words, created economic systems, landscapes, politics and philosophies—did you go down any rabbit holes of research, or were you just making it all up as you go along?

PB: Sfaiculo! That’s not faux-italian! That’s Navolese!

But yeah, I did end up doing a fair amount of research. I did it in fits and starts. I read a lot of political history, family histories of the Medicis and Borgias, histories of the condottieri, the mercenary armies, histories of economic development in Europe and international trade, of Da Vinci and Machiavelli, of architecture and culture. I had a great time reading Machiavelli’s comedies, for example, which he’s not known for but are in interesting side aspect of his larger life and works. I didn’t want to re-created Italy or the Renaissance period, I wanted to loot the furniture and turn it to my own purposes.I also spent a few months in Italy at one point, studying Italian with a friend, and poking into food and architecture, and sort of absorbing whatever seemed interesting about the place. That was when I started playing around with creating my own culture-specific dialect for Navola—sfaccire, stilettotore, faccioscuro, parlobanco, sfaiculo, etc.

MM: The fantasy elements are woven very subtly into this novel. The major theme is not dragons; it’s Machiavellian plots, power plays and parental pressures, it’s a money mafia family history, as it were. Did you ever want to (or feel pressure to) lean into the fantasy elements more? Or was it exciting to be away from that and explore something new?

PB: Well, Navola originally wasn’t intended to be published at all, so I never felt any pressure one way or the other. When I finally decided that it was actually a book and I submitted it to Knopf, I liked all the scheming and plotting and power plays, and the questions of who is trustworthy and who was not—and I liked that magic lurked in the background, with its memories of its old gods, its myths of a larger weave of nature, and its fossilized dragon eye, signaling that there are often powers that we cannot fully understand or control, but may still lurk, and may still exert influence.

MM: I recall an interview with Lightspeed magazine in 2011, in which you said as proud as you were of ShipBreaker, with WindUp Girl you constantly felt ashamed. I wondered how you felt about those books now, so many more years down the line, and how you feel about Navola, which is a world you’re still living with for the sequel.

PB: Oh yeah. That was a tough time in my life. I wasn’t used to the attention yet—the positive or the negative. Now, at this point, I’m actually really proud of everything I’ve written. I’ve written ten books now, and I know why I wrote each one, whether it was The WindUp Girl or my middle-grade novel Zombie Baseball Beatdown. Some of those books have won awards, some have been bestsellers, and some haven’t, but I’m just delighted and a little in awe that I had the imagination to create any of them. As for Navola and its sequel, I’m halfway into writing the sequel and I just wrote a sequence of scenes that made me laugh out loud, so I’m having a delightful time.

MM: Climate change fiction can be depressing—much like our current reality of course, but as a writer you’d really have no escape. Were Navola‘s intrigues a respite for you, as grim as politics and poisons and murders can be?

PB: Absolutely! In the world of Navola, the glaciers never melt in the icy high mountains of the Cielofrigo, and in the deep Romiglia stone bears and shadow panthers and mist wolves and fatas still thrive under the shade of whitebark, in clear crystal pools and beside crashing waterfalls. Nature still thrives in that world, and it stands on equal footing against the intrusions of humanity. What a blessing it is to imagine a world where some balance still exists.

Buy the Book

Navola