Physics is no respecter of human desire. It’s unfortunate that:

- the Earth’s escape velocity is what it is,

- the exhaust velocities of rockets currently available to us aren’t as high as we would like,

- and the rocket equation is what it is.

This means that a lot of fuel and reaction mass must be consumed to put a comparatively small payload into orbit. Thus, one current coping mechanism: using micro-electronics to cram as much capacity as possible into the payload available.

Would it be possible to miniaturize astronauts as well? In real life, not so much. But SF succeeds where real life disappoints. Consider these five works that imagine low-mass astronauts…

The Space Merchants by Frederik Pohl and Cyril Kornbluth (1953)

Having transformed the Earth into a capitalist utopia in which every person’s consumer potential is optimized, Earth’s corporate eyes fall on Venus. Grim reality intervenes. The rockets available are insufficient to deliver a conventional adult male scout to Venus.

Enter Jack O’Shea. He’s only thirty-five-inches tall (he’s an adult little person) and he consumes a third of the supplies needed by other astronauts. O’Shea succeeds where others would have failed. True, the Venus he explored is a nightmarish hellhole, not the paradise Earth would have preferred, but selling it to colonists won’t be O’Shea’s job. That task falls to society’s heroes, ad men like Mitchell Courtenay.

Modern readers might wonder why Earth didn’t use a robot probe. The simple answer is the book was written before compact electronics were available. The authors assumed that humans would of course weigh less than clunky machinery. Or at least, small humans would.

Capitalism may frequently suck, but it is willing to extract value from anyone, regardless of age, creed, race, willingness, and in this case, stature.

Blast Off at Woomera by Hugh Walters (1957)

Had the British-Australian space program sufficient time, they would build a rocket able to deliver an adult male to orbit. As alien structures of uncertain intent have appeared on the Moon, there is no time to develop larger rockets. What the space program needs is a qualified crewmember who can be crammed into the existing vehicle.

Seventeen-year-old Chris Godfrey is bright, educated, an orphan with few relatives to complain if he does not survive, and most importantly, he’s just four foot, eleven inches tall. Godfrey is the ideal candidate for the orbital mission… if the dastardly Reds do not succeed in sabotaging the mission.

Readers might wonder if qualified women were considered. They were not. Interestingly, unlike many SF novels of this era, the text suggests that such women did exist—Chris’ aunt Mary is a capable woman, as is intelligence agent Miss Darke. It seems likely that Chris would have had a distaff analog. However, certain cultural blinders seem to have kept the space program from considering women1.

The Ship Who Sang by Anne McCaffrey (1969)

Central had no use for most of Helva, but quite a lot of use for some of Helva. Having determined to their satisfaction that the deformed baby was cognitively suitable for the role intended, Central’s doctors discarded Helva’s body and installed her brain in interstellar ship XH 834.

Converting Helva into a Brain was expensive. Maintaining Helva is expensive. If Helva works very hard, she might pay off her debts. What hard work will not protect her from is the reality that Brains are almost immortal, while their human crews are not, or from the grief that follows when beloved humans died.

Readers worried that the setting is a bit ableist can rest assured that, in fact, the setting is enormously ableist. One cannot help but notice that the comprehensive prejudice shown towards people like Helva facilitates certain economic ends, which might explain why attempted reforms fail abjectly.

Joe 90: “Most Special Astronaut” by Alan Perry and Tony Barwick (1968)

When a manned supply rocket goes off course, mission control has no choice but to order it to self-destruct2. This leaves the two astronauts in the orbiting space station with just three days of air. Supplies must be delivered… but no astronaut is available to pilot the mission.

Enter nine-year-old World Intelligence Network agent Joe McClaine. Thanks to his father’s invention, the Brain Impulse Galvanoscope Record And Transfer3, skills from qualified persons—such as injured astronaut Charles Drayton—can be temporarily decanted into Joe’s brain. The orbiting astronauts will surely be saved… but it may be best if they don’t suspect that their lives are in the hands of a nine-year-old.

Joe’s age and stature is an asset from WIN’s point of view, but not because of fuel efficiency. Most of Joe’s missions, many surprisingly grim given that the protagonist is nine, are espionage-related. Few people would suspect a boy of being a highly skilled secret agent, neurosurgeon, or pilot.

Rocket Girls by Hōsuke Nojiri (1995)

The Solomon Space Association4 LS-7 rocket is satisfactory in all ways, save for its tendency to violently explode when launched. The LS-6 is more reliable but its payload is insufficient to deliver SSA astronaut Haruyuki Yasukawa to orbit. SSA is at an impasse… until a chance encounter with Japanese schoolgirl Yukari Morita.

Yukari is bright, small, available, and desires something only SSA can provide, the current location of her long-lost father. Blackmailed into crewing the LS-6, Yukari proves an adept astronaut5… and in short order, so does Yukari’s half-sister Matsuri. One can never have too many backup girl astronauts, given the possibility of fatal mishaps in space.

By modern standards, Rocket Girls is a short novel. Nevertheless, it contains the full plot of a much longer book. It is a tribute to what can be accomplished by an author who embraces improv’s No Blocking rule. It does not hurt that SSA has an impressive clarity of purpose and a comprehensive disregard for minor distractions like “ethics.”

Have I overlooked obvious examples (aside from Rocket Girls’ sequel)? Feel free to name them in comments below.

- I believe this oversight was addressed after the formation of the world space program UNEXA

- Gerry and Sylvia Anderson’s TV series were often surprisingly cold-blooded, and their Joe 90 is no exception.

- My personal explanation for the rotating actors in the Bond franchise is that MI5 uses BIG RAT to impress Bond memories from successful missions into the brains of new host bodies.

- The author’s painstaking research into the Solomon Islands and its peoples appears to have consisted of checking the spelling of the Islands’ name, and determining that its latitude was suitable for his purposes.

- SSA tends to see consent as an obligatory but annoying impediment… but not only does Yukari agree after only a little unethical suasion, her mother is fine with her daughter’s occupation. After all, life is short and Yukari could get run over crossing the street. Why not invest precious moments in an important program? Rocket Girls is pre-Truck-kun, so crossing the road was not the death sentence for Japanese persons that it is today. Nevertheless, Rocket Girls is not the only Japanese SF work featuring a protagonist whose mother supports their child entering a dangerous field on the ground that death is inevitable but meaningful work is not.

Kelly Robson’s Gods, Monsters, and the Lucky Peach has a character amputate her legs to fit in the time travel vehicle. If I recall, the other characters are smaller, due to childhood malnutrition

Ray Bradbury’s radio play “Leviathan 99” has very short space explorers, presented as kind of a spacer subculture if I remember right. They’re not the whole crew of the Cetus 7 but they’re a big percentage.

I like your rationale for the various Bonds.

This is a major plot point in Curious George 3: Back to the Jungle. For reasons, NASA needs help with a space mission, because their jury rigged space capsule to perform needed repairs no longer has space for an actual qualified full size human astronaut.

If you are familiar with Curious George … well, things go about as well as you could expect with him.

I always figured Little People would have an advantage in space, though I haven’t featured the idea in my fiction as often as I feel I should have, the one significant Little Person in my fiction to date being Sally Knox, a supporting character in my Troubleshooter series. However, in my Arachne soon-to-be-a-trilogy, I established that the interstellar expedition favored relatively small crew members where possible, with one of the two female leads being 4’11” and only two characters taller than 5’9″.

My Analog story “Abductive Reasoning” posits that interstellar travelers store their consciousnesses in biochips on tiny wafer-ships that drift through space relativistically and can 3D-print organic bodies around themselves upon making planetfall. The story involves a UFO believer meeting a real alien who pokes holes in his belief system, and I wanted the spaceflight method to be as unlike flying saucers as possible.

IIRC, Helva and the other Ships (and Cities and Stations) have their growth intentionally stunted to keep them physically small.

Per my memory of the opening chapters of the first novel from years ago, so grain of salt:

Candidates are specifically those who have no cognitive deficits but were born into bodies not compatible with life. Baby Helva had rocker-bottom feet, among other physical differences, which implies that she had a genetic syndrome that required life support from first breath. (Do not look up what syndromes those might be unless you are prepared to see some horrific photos. I don’t mean funny-looking kids. I mean not compatible with life.) Candidates keep their original bodies, but are hooked into increasingly mobile life-support systems that take care of nutrition, muscle tone, etc. Toddler Helva scooted around in a can on treads and interacted with the world via cameras and robot arms. Her can was periodically enlarged and improved until she decided on her adult profession. She could have run a space station or become a data administrator but chose the brainship program instead. She is “installed” in the bulkhead of her ship-body with a locked access door for medical purposes. Her human partner (“brawn”) falls into mutual obsession with her and she almost colludes with him in getting the door open so that they could actually touch, although that would have probably killed her, the brawn not having access to PPE or any medical training.

The short stories may vary, but, consulting Wikipedia but not the fixup itself which I think I own, there may be not much of Helva but she isn’t a brain in a jar. As I said on a clones-for-transplants story discussion, human organs, including the brain, work best with most of the rest of the set present, even if Helva’s brain can’t usefully sense or act on the outside world without connections to electronic equipment. But her physical self is sealed in a pod which provides life support.

I acknowledge that ableism incorporates prejudice that should be avoided, but also, I have abilities and I enjoy them. Being ability shortchanged sucks, in my opinion. But we’d better appreciate what we have got. As for being embodied in a spaceship, I wonder if it’s really more fun at all than being a car or a train, which I haven’t recently thought of being when I grow up – anyway, I am past 50.

McCaffrey and other authors in the universe tried to make it less ableist but, hoo boy… I think they gave up sometime in the mid-80’s. Or maybe I did..

I don’t think it’s directly stated but it is clearly implied.

I also interpret the selection process being based on disabilities at the level of “will die in screaming agony within hours of birth” and not “will be in a wheelchair.” From the numbers given, there a perhaps a hundred shellpeople a year from a civilization with at least a dozen planets of over a billion people.

I’m fairly sure that it was directly stated somewhere that Helva still had her original body (still the size of a child), and that it was hooked up to intensive automated medical and life support systems.

Having the original body is not the same as that body ever having been able to survive without constant intervention. One of the other shellpeople is described as using an entirely fictitious avatar because his deformities are so extreme as to be instantly horrifying.

Pournelle’s King David’s Spaceship went the route of considering *gasp* a woman to crew their kinda-sorta Orion bomb ship. Who cares that the many thousands of explosions would completely pulverize her internal organs from the shock waves and they had no way of getting her back down; they still succeeded in putting her into orbit, thus keeping their world from being enslaved by the massive, uncaring Empire which had come along and ‘discovered’ them while they were busy minding their own business.

Though dealing with space colonists more so than Earth-based astronauts, James Blish’s 1952 story “Surface Tension” did give us genetically-engineered micro-humans. The ethical issues of paramecium people didn’t seem a thing back then

I immediately thought of this story although it’s probably 40 years or more since I read it but I still remembered the enjoyment I had at reading such a clever concept.

And then there’s Neptune’s Brood by some guy called, oh, I forget, which opens thuswise:

“I can get you a cheaper ticket if you let me amputate your legs: I can even take your thighs as a deposit,” said the travel agent. He was clearly trying hard to be helpful: “It’s not as if you’ll need them where you’re going, is it?”

(Our heroine has made the awful mistake of trying to book a fast transit between an outer system habitat and an inner system water world just the wrong side of a conjunction in a universe that doesn’t have an applied phlebotinium space drive, so everything mass-related is insanely expensive.)

How about Emergence, by David Palmer? IIRC, an 11 or 12 year old girl gets sent into space to defuse a doomsday device.

That was more of a plot device to get her into space. The ship carried two full-size men and was intended to also carry a robot small enough to crawl through the inconveniently-sized hatch in the Soviet orbital bomb Buran yet also strong enough to do the disarming.

But nobody could build a robot both small and strong, so she got to go instead.

MI-6 (SIS), surely.

There’s David Langford’s The Space Eater (1982), wherein the largest safe wormhole is one point nine centimetres across, necessitating a certain amount of reconstructive surgery for our unlucky volunteers upon arrival.

In Joe Haldeman’s Worlds trilogy, interstellar travellers underwent something like freeze-drying in order to make the trip. They weren’t conscious in this state but they did take up less room.

In John Varley’s The Ophiuchi Hotline, a black hole hunter who spends all of her time in her hole-hunting ship has whittled herself down to an arm, a leg with a modified hand on the end, a head and a reduced torso. The living quarters of her ship consist essentially of a series of narrow tubes and small spaces too small for a normal human to enter.

After reading Rocket Girls I was surprised to learn it was written in ’95. Its take on corporate-run human spaceflight felt very contemporary.

Corporations never really change — their behavior now is no different from their behavior in past decades. So it’s pretty easy to project how they’d approach spaceflight.

Most works of fiction that seem prophetic in retrospect are only that way because human behavior and institutional behavior are generally predictable and follow recurring patterns. Such stories are usually commenting on the way things are in their own time, or positing a recurrence of stuff that happened in the past. Since patterns always repeat, eventually they’ll be timely again.

Victor Koman’s short story Bootstrap Enterprise also features astronauts having their legs amputated to save mass.

In one of Spider Robinson’s later “Callahan’s” books (one of the post-Place ones), a small girl is teleported into a rocket carrying … I don’t remember what, but something desperate for the survival of the future Mike Callahan comes from … to ensure its survival. Because reasons.

Pat Murphy’s There and Back Again has a Norbit as a main character. Norbits are small human-type people who live in holes in

the groundasteroids and drive steam-powered rockets. (No, this is not steampunk.)Now I have to ask myself if “The Clangers” is steampunk. In the recent (2015 ish) revival, space contains modern ish technology, although recognisable to late 20th century survivors, and strange alien techno-organic life, but the Clanger community has a lot of Rube Goldberg apparatus that Major Clanger adapted from 1940s looking junkyard stuff which I’m not sure how it got to there. Maybe 1940s-50s UFOs were really coming to Earth for scrap metal. It’s certainly old-stuff-punk, and I think they have speaking tubes, but possibly in a mobile version.

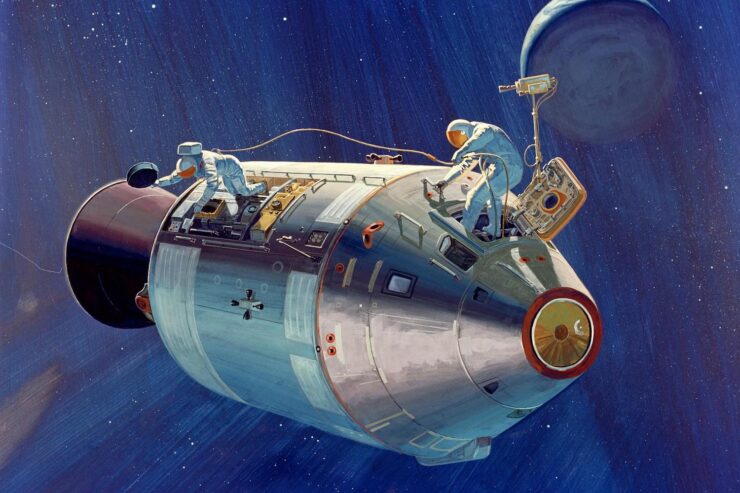

Can I just say that the astronaut in the header picture looks like they’re repairing their spaceship by whacking it with a cast-iron frying pan?

Now you’ll never be able to unsee it.,

You’re right about UNEXA eventually allowing female astronauts… on re-reading the Hugh Walters books a while back, I found they weren’t quite as bad about representation as I’d remembered, though still being pretty bad; the series does, at one point, consider possibly flirting with maybe thinking about perhaps having a try at passing the Bechdel test (it doesn’t), and at one point Walters introduces a staggeringly diverse crew, consisting of an Englishman, an Irishman, a Welshman and a Scot.

Joe 90 is one of those things that is pure fun if you don’t think about it, and absolute nightmare fuel if you do. Joe gets to be a jet pilot! and an astronaut!! and a secret agent!!! Pure wish-fulfilment fun. And then you take a step back, and notice that it’s all about a reclusive scientist doing hideously unethical experiments on a child’s brain, and then endangering that child by placing him in absolutely appalling situations. It has long been my opinion that Joe is Joe 90 because the unsuccessful experiments Joes 1-89 are buried in unmarked graves around Professor MacLaine’s isolated country cottage, and the whole “World Intelligence Network” thing is just the Professor trying to get Joe killed in some non-recoverable way before the adoption agencies catch up with him. (Yes, I reckon Joe is adopted. Professor MacLaine drives [and flies] around in a car with plutonium bodywork, of course he’s sterile.)

Falling Free by Lois McMaster Bujold has “quaddies”, workers on a space station who were genetically engineered to have a second set of arms in place of legs. Saves space and gets more work done in free fall! Unfortunately the technology they were bred to work on has become suddenly obsolete, and it’s going to be more cost effective to dispose of the experimental subjects…

The company that created the quaddies classified them as “post-fetal experimental tissue cultures”, and claimed that they were therefore exempt from regulations and laws intended to protect humans.

I remember reading that one in Analog. Was it one of her first?

It was early on, certainly. Shards of Honor, The Warrior’s Apprentice, and Ethan of Athos were before that one.

Ender’s Game went with this plan, although the child soldiers didn’t get to go to space.

Today I learned that “Norman” is short for “North American.” What’s up with that image credit?

North American Rockwell was a defense/space contractor. IIRC, they built a good bit of the Space Shuttle. I can’t recall if they got absorbed into Boeing or Lockheed…

Now split into Rockwell Automation & Rockwell Collins, per Wikipedia!

William C. Anderson’s novel Adam M1 (1964) solved this one by putting the astronauts brain into a humanoid robotic body, so that they only needed power and enough nutrients and water to keep their brains alive. As I recall it the bodies looked reasonably human, and the hero ends up on the moon with his (similarly modified) girlfriend. I don’t recall them going into many details of the mechanics of their relationship, but I was about 13 when I read it as a library book so I suspect they weren’t very explicit.

Geoffrey Landis’ Approaching Perimelasma; I think the protagonist is smaller than any other suggestions bar the puddle-dwellers of Surface Tension, and it’s on purpose to deal with a very particular part of space….

Available at Infinity Plus, here: https://www.infinityplus.co.uk/stories/perimelasma.htm

Honorable mention to Asimov’s Fantastic Voyage, I suppose, even though the space involved is “inner” :)

It’s not Asimov’s; he just novelized the movie. The concept originated with a story by Otto Klement & Jerome Bixby, with Harry Kleiner writing the final screenplay. But back then, movie novelizations were sometimes released before the movie to generate buzz, in this case six months before. So a lot of people have mistakenly assumed the movie was an adaptation of the novel rather than the other way around.

Though it’s true that Asimov made the story his own to an extent, adding a lot more plausible science to the novel than there was in the movie, and changing the ending to fix a major plot hole. And he wrote a later novel called Fantastic Voyage II: Destination Brain, which was not a sequel but his own original approach to the basic concept.

Two things:

Not strictly a problem of size (but definitely of mass – any “extra” mass) was a take on the unbending, not-to-be-messed-with laws of physics, namely “The Cold Equations”, by Tom Godwin.

I believe it was turned into an “Outer Limits” script, too, much later on.

Corey Doctorow just eviscerated it later on.

James Blish (who did the novelization of a lot of the Star Trek OS) in the 1950’s did various short stories on this theme collected as The Seedling Stars. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Seedling_Stars

In David Palmer’s EMERGENCE, our heroine is surprisingly able for her years.

However, my preferred Tiny Astronaut would have be Lisa Simpson.

I had never heard of Joe 90, but the name Joe McClaine reminded me of a fever dream cartoon called Bruno The Kid. A kid applies online for a job with GLOBE, a super spy outfit, using a virtual avatar voiced by, and looking like, Bruce Willis in the middle of Die Hard. Of course he gets the job. When his assigned assistant/chauffeur arrives to pick him up for their first mission, he goes along for it for reasons never adequately explained. His small size was also often useful.

Oh, yes, I kind of remember that show. Bruno the Kid was actually created and executive-produced by Bruce Willis, who voiced the real Bruno as well as his virtual avatar. I think “Bruno” is Willis’s own nickname, so the character was basically a kid version of himself.

I was interested to discover that in all these examples, the space travellers keep some mass. My first thought when I saw the title was The Light Brigade by Kameron Hurley, in which soldiers are transformed into light to be sent to the frontlines of the space war.

he Game of Rat and Dragon uses telepathically linked cats and humans. Too easy perhaps?