In this bi-weekly series reviewing classic science fiction and fantasy books, Alan Brown looks at the front lines and frontiers of the field; books about soldiers and spacers, scientists and engineers, explorers and adventurers. Stories full of what Shakespeare used to refer to as “alarums and excursions”: battles, chases, clashes, and the stuff of excitement.

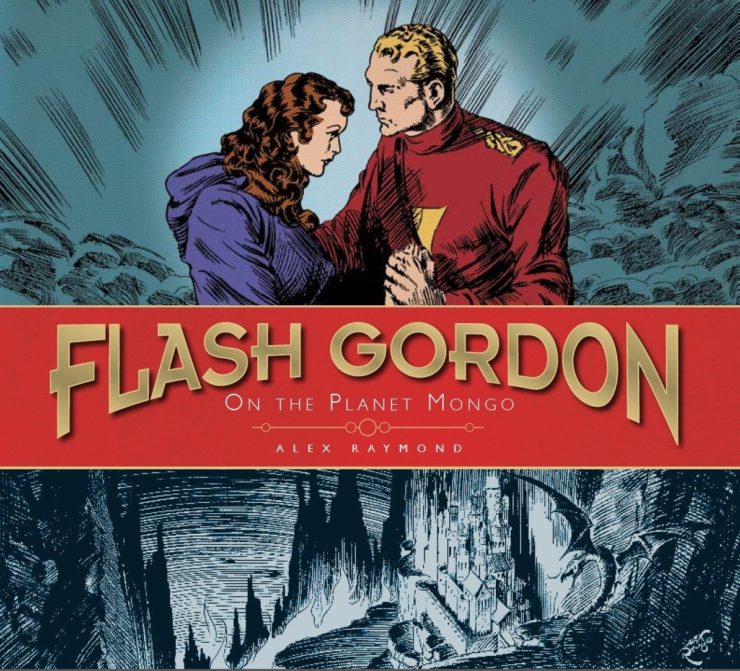

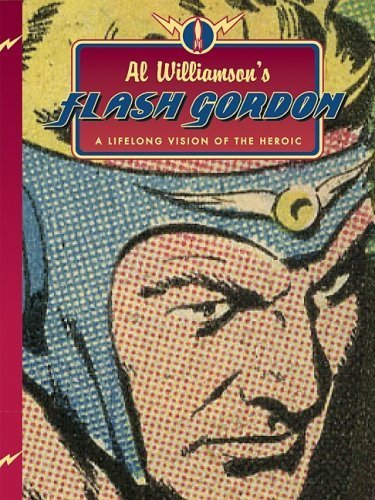

Over the years, I’ve looked at some of the most influential characters in science fiction in this column, mainly figures like Buck Rogers who emerged from the pulp magazines or from books, but this time I’m turning the spotlight on a character who first emerged from newspaper comic strips: Flash Gordon. And because comics are a visual medium, instead of focusing on writers, I’m going to focus on artists by looking at two coffee table books: Flash Gordon on the Planet Mongo by Alex Raymond (from Titan Books), and Al Williamson’s Flash Gordon: A Lifelong Vision of the Heroic (from Flesk Publications). So let’s strap on our blaster pistols, prepare to crash a spaceship, and set our sights on the planet Mongo!

Flash Gordon was born in 1934 when the King Features Syndicate wanted a new science fiction action adventure to compete with the success of the Buck Rogers newspaper comic strip. When efforts to license Edgar Rice Burroughs’ Barsoom series failed, they turned to an in-house creator, Alex Raymond, and promptly hit pay dirt. The comic strip started running on Sundays in 1934, and in 1940, daily strips were added. The daily strips ended in 1992, and the Sunday strips ended in 2003—a remarkably long run in a volatile business. In addition to Alex Raymond, the strip was drawn by Austin Briggs, Mac Raboy, Dan Barry, Ralph Reese and Bruce Jones, Gray Morrow, Thomas Warkentin and Andrés Klacik, Richard Bruning, Kevin Van Hook, and Jim Keefe. Several writers worked on the strip, including Don Moore, who assisted Alex Raymond in the early days, and noted science fiction writer Harry Harrison.

About the Artists

Alex Raymond (1909-1956) was a cartoonist for King Features Syndicate. His most famous creation, Flash Gordon, went on to great success in its own right in a variety of media. He also worked on Jungle Jim and Secret Agent X-9. Raymond served as a Marine in World War II, and returned to create the long-running strip Rip Kirby. In a medium where deadlines were tight and quality often suffered as a result, he was known for intricate and careful detail. Raymond could draw realistic, lifelike images when needed, but was also highly imaginative in presenting the creatures, technology, architecture, and peoples of the mysterious world of Mongo.

Al Williamson (1931-2010) was inspired to become an artist when he encountered Flash Gordon during his youth. He worked for a variety of comic companies, including Atlas, EC, Harvey and Warren Publishing. He then assisted with the Alex Raymond-created Rip Kirby newspaper strip. In the mid-1960s, he drew a well-received series of Flash Gordon comics for King Features (and won a National Cartoonists Society Award for Best Comic Book). He then took over another Raymond-created strip, Secret Agent X-9 (retitled as Secret Agent Corrigan). In the 1980s, he began a long collaboration with Marvel comics by illustrating a comic based on Star Wars: The Empire Strikes Back. He also worked on a short-lived Star Wars newspaper strip. While he did draw more comics for Marvel, including Star Wars and Flash Gordon books, he decided doing both penciling and inking was too stressful, and became an inker on several books, my favorite of these being Spider-Man 2099.

Alex Raymond and the Origin of Flash Gordon

While I have long been a fan of Flash Gordon, and had seen numerous examples of Alex Raymond’s art over the years, until recently I had never seen the original newspaper strips. That changed when my son gave me the Titan Books collection of the original Sunday strips entitled Flash Gordon on the Planet Mongo. The book is gorgeously bound, a fitting format for this seminal work, and contains excellent historical material as well.

Through the book, I got to see the original vision for the character: A mysterious planet is hurtling toward Earth. Flash Gordon, Yale graduate and polo player (fortunately but incongruously wearing a parachute on a passenger plane), meets the young woman sitting next him, Dale Arden (who has no chute). When the plane is hit by a meteor, he gathers Dale in his arms and rescues her. They land in the yard of Doctor Hans Zarkov, who has built a homemade spaceship. He forces the two aboard at gunpoint so they cannot steal his ideas and blasts into space…and that’s just the first Sunday strip!

Over the next two Sundays, Zarkov’s ship crashes on the wandering planet Mongo, and Dale is injured. Flash heads out toward a nearby city to find treatment for her. They almost fall prey to not just one, but two dinosaurs, and are picked up by the rocket forces of the evil Emperor Ming, who throws Flash into his arena to fight against giant beast men. Flash defeats them, but his reward is Ming to ordering his execution! Fortunately, the Princess Aura has taken a shine to Flash and helps him escape—Flash returns the favor by rescuing her from monsters. Then Flash, after meeting a Lion Man whom he befriends, heads back to rescue Dale, who has been placed in Ming’s harem.

This establishes a frequently repeated template for Flash’s adventures. He crashes somewhere (rockets on Mongo always seem to have landing issues), Dale is lost or injured, Flash battles a monster, he battles some sort of beast men, he is seen by a queen or princess who immediately falls in love with him, he battles another monster or two, and soon everything is set right thanks to Flash’s cleverness, battle prowess, or both. Flash and Dale exhibit little in the way of personalities, with the frenetic plot driving their actions. Although they had just met for the first time on their airliner, the two develop a strong romantic bond, although marriage is a goal that always evades them. Flash must have been in the ROTC in college, because in addition to being an excellent horseman, he is also a skilled fencer, boxer, and marksman. Dale is plucky and brave, but usually needs help getting out of scrapes. Zarkov, who at first puts the “mad” in the term “mad scientist,” becomes more useful in future episodes, often inventing something on the fly to help foil Ming’s plans. Reading the strips one after the other can get monotonous, but you have to remember they were written to be read once a week, with a story simple and memorable enough to allow the readers to pick things up in the next installment.

While the strips lack in nuance, they are absolutely gorgeous to look at. Dale and Flash are drawn as handsome people, and are often scantily clad, him shirtless, and her forced into a brass brassiere and gauzy skirt by her captors (the attire is scanty even by today’s standards, and I can imagine it caused some consternation back in the days when a bathing suit without a skirt was considered racy). The backdrops are lush and filled with interesting details. The art is beautiful, intricate, full of action, and gets better with each passing week. Alex Raymond was known for putting a lot of extra effort into his art, and it shows. The only drawback is the indifferent and garish coloring that was a byproduct of the printing technology of the times.

There are some dated attitudes. The female characters only seem to exist in order to fall in love with someone (often Flash), occasionally cast some sort of magical spell, and/or to be captured and need rescuing. The fighting and building is done only by men. The people of Ming’s city are portrayed with canary yellow skin, and Ming fits the offensive Yellow Peril stereotype of a scheming Oriental ruler common in the era. But the later introduction of the noble Prince Barin shows the evil Ming and his minions were an aberration among their people, and the narrative generally avoids much of the blatant racism that marked the early adventures of Buck Rogers.

Mongo itself is a perfect setting for planetary romance, filled with all sorts of mysterious people, monsters, cities and nations. There are witch queens, underground cities, undersea nations, flying people with floating cities, and all manner of marvels to keep the readers engaged. The Raymond era was full of fast-paced action and fun adventure.

Al Williamson Keeps Flash Alive

I first encountered Flash through Al Williamson’s work, in the form of the award-winning King comic books from the 1960s, and I have always had a special fondness for his work. While the narrative in the newspaper strips had been moved from a Mongo-based planetary romance to a star-spanning space opera, Williamson wisely went back to the character’s roots, having Flash return to Mongo. I read those comics to tatters, and when I saw the Flesk Publications book Al Williamson’s Flash Gordon: A Lifelong Vision of the Heroic in 2009, I immediately snapped it up. I was rewarded with black and white reproductions of nearly every Flash Gordon work he had ever drawn, along with biographical material on the artist and historical material on the character. Not having the color illustrations was actually an improvement, as the comic coloring process of the day usually detracted from the drawings themselves.

The book begins with Flash, Dale, and Zarkov returning to Mongo to procure radium for use by Earth’s peacekeeping forces, and after a quick recap of Flash’s previous adventures, they get caught up in palace intrigue as they visit the land of Frigia. Williamson does a great job weaving new characters in among the old favorites, and while his art pays homage to Raymond’s original vision, he also brings fresh new elements to the visuals. His drawings are gorgeous, full of energy and interesting perspectives. His use of different line thicknesses and shadowing draws your eyes to exactly where they need to go. Williamson brings the team home to Earth for an underground adventure, and then back to Mongo and a lost continent, where they (after the obligatory crash landing) encounter many mysteries, and even encounter the mysteriously revived Ming the Merciless.

The book also features some miscellaneous drawings of Flash and company from over the years, and even a series of single-page advertising adventures where the team plugs the plastic products of Union Carbide. It contains the comic book adaptation of the 1980 Flash Gordon movie—a project Williamson did not seem to enjoy working on. He reportedly didn’t think the actors who played Flash and Dale looked the part, didn’t feel the movie was respectful to the spirit of the stories, and was irritated when last minute changes forced him to redraw portions of the comics.

The book ends with reproductions of the last Flash Gordon comics Williamson drew for Marvel, working without the photo referencing he had to use extensively for the movie adaptation, and without deadline pressures. Here we get to see the artist’s vision with little editorial interference, and it’s a fitting conclusion for his long relationship with the character.

While many fine artists have chronicled Flash’s adventures, and Raymond deserves full credit for originally bringing the character to life, Williamson’s version will always be my favorite.

Flash Gordon in Other Media

Flash and his friends have appeared in many kinds of media besides the newspaper strips. There was a radio program recounting the same story as the strips. There were movie serials starring Buster Crabbe (who also starred as Buck Rogers, causing me much confusion when watching them on TV as a youth). The first of the three serials began with the planetary romance setting of Mongo, with the second shifting the action to Mars (to capitalize on a then-current fascination with the planet), and the third becoming more of a space opera battle for the fate of the universe. There was also a short-lived TV series in the 1950s, several other low-budget feature films (including a pornographic parody, Flesh Gordon), and a TV cartoon version in the late 1970s.

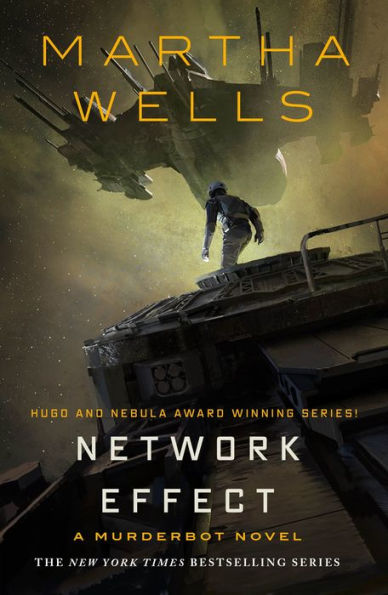

Buy the Book

Network Effect

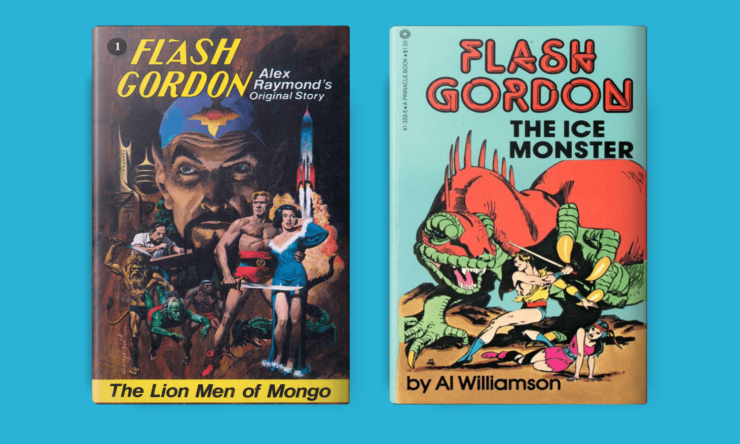

A number of Flash Gordon books have appeared over the years. For a brief time, there was a pulp magazine, and several Big Little Books. I found two paperbacks in my personal collection. The first, published by Avon Books in 1974, is Flash Gordon: The Lion Men of Mongo, and is marked as the first book in a series adapting “Alex Raymond’s Original Story,” and labelled as being “adapted by” Con Steffanson (reportedly a pen name for Ron Goulart). He did a good job in updating the story, adding detail, and making it flow a bit more smoothly than the “monster of the week” approach of the original strips. But in the process, the story also loses some of its frenetic energy. The second book is Flash Gordon: The Ice Monster, credited to Al Williamson, and published by Pinnacle Books. This book collects black and white reproductions from the King Comic books of 1966. It is notable in being marked as a Tom Doherty Associates Book, from the days before he founded Tor Books.

Most people today associate the character with the 1980 movie Flash Gordon, which, while not a box office success on its first release, has developed a loyal following over subsequent years, with a bombastic soundtrack by the group Queen that’s perhaps more memorable than the film itself. Famously, after trying to obtain the rights to Flash Gordon and failing, director George Lucas found wild success with Star Wars in 1977, a film that in many respects was an homage to Flash and his adventures. The success of Lucas’ effort led to many other big-budget science fiction movies—including, ironically, a new version of Flash Gordon. It was a big, splashy, colorful and lavish affair, produced by Dino De Laurentiis, which captured the look of the comics perfectly. The supporting cast was full of big-name stars whose scenery-chewing performances worked because they were obviously having fun. Unfortunately, the lead roles of Flash and Dale were played by Sam Jones and Melody Anderson, whose performances were wooden and underwhelming. While I enjoyed some elements, I did not care for the film overall, as it felt like the campy production was mocking the character and settings I loved.

Flash continues to appear from time to time in TV incarnations, but none of them has had any great success. There have been a few more short-lived comic book adaptations over the years. And while there have been a few rumors about new film treatments, none has come anywhere near fruition.

Final Thoughts

So, there you have it: the history of Flash Gordon, one of the most famous characters in science fiction, and one who is unique in having emerged from the comic pages of the newspapers. Plus a look at two books that offer different perspectives on the character in the hands of two wildly talented artists: Flash’s creator, Alex Raymond, and one of Raymond’s most worthy successors, Al Williamson.

And now I turn the floor over to you: What are your favorite incarnations of the character, and favorite artists who drew the character? When and where did you first encounter Flash, and did that version remain your favorite as you saw the character come to life in other settings?

Alan Brown has been a science fiction fan for over five decades, especially fiction that deals with science, military matters, exploration and adventure.