Welcome back to Reading the Weird, in which we get girl cooties all over weird fiction, cosmic horror, and Lovecraftiana—from its historical roots through its most recent branches.

This week, we cover Arkady Martine’s Rose/House novella, just released this year by Subterranean Press. Spoilers ahead—but we highly recommend grabbing the ebook and reading it yourself first!

“I’m a piece of architecture, Detective. How should I know how humans are like to die?”

Rose House is haunted, like all of Basit Deniau’s houses; last and best, it’s the one he chooses to be enshrined in, his ashes compressed into a diamond and mounted in the house’s heart. Twenty-second century houses commonly have embedded AIs. A “house…infused in every load-bearing beam and fine marble tile with a thinking creature that is not human?” That’s Rose House, singular, “curled like the petals of a gypsum crystal in the shadow of a [Mojave desert] dune,” the nearest town tiny China Lake.

Besides Basit’s remains, Rose House contains his intellectual treasures, sketches and archival material for which every Deniau-groupie yearns. Basit’s will, however, grants Rose House access only to his executor, for one week a year.

That executor is Selene Gisil, Basit’s star student and one-time idolizer. Eventually, she denounced his houses as “poison palaces built for his own glorification”. Bequeathing Rose House to Selene seems Basit’s way of enthralling her back into his influence. She’s stayed there just three days out of her permitted week, watched by “diamond-cold” Basit and the house itself.

Selene’s in Turkey when a China Lake police officer calls: Rose House (per the Federal AI Surveillance Act) has notified them of a dead human within its boundaries – but refused to explain further. It’s a house, after all: how should it know how humans are like to die? Selene is Detective Maritza Smith’s sole way inside. She’s tried to get in on her own, only to be turned back by the cryptic-mocking question, “What is a building without doors?”

Selene agrees to take Maritza to Rose House that evening, but does “a necessary errand” first. Maritza receives a call from journalist Alanna Ott, who’s learned that Selene’s in town, and warns that Maritza may hear from persons with particular interest in Rose House.

Oliver drives the women to Rose House. It welcomes Selene but bars other persons. Selene claims that Maritza’s not a person but the personification of China Lake Precinct. Rose House accepts, and Maritza enters over Oliver’s objections.

The corpse lies in the house’s library, beneath Basit’s plinth. It’s a Caucasian male, thirtyish, well-dressed and well-rotted despite refrigeration. There’s no sign of violence, except for the fresh rose petals stuffed in his mouth. Eye-hemorrhaging suggests asphyxiation. Rose House riddles Maritza and infuriates Selene, who flees to an alcove off the Escheresque central hall. She’s aware that the plastic sliver in her pocket is a “prize” insufficient to free her from Basit.

Outside the station, Oliver encounters Alec Goodspeed, “representative” of an auctions firm. A “colleague” interested in Basit’s plans for living cities believes Selene’s in China Lake. Told she’s left town, Goodspeed departs. Oliver’s internet research suggests Goodspeed is one of a group of fanatics devoted to making all architecture alive, like Rose House. Oliver’s call to Maritza is cut off. He then calls Maritza’s well-informed journalist, who says that Basit’s Andorran countrymen want to repatriate his archives. Oliver tells her about the dead man and Goodspeed. Whether Goodspeed’s legitimate lawyer, rogue Andorran, or some other Deniau-groupie, Oliver’s busting him. Alanna comes along.

Maritza continues playing “precinct”. Rose House reveals that the intruder wanted access to the sublibrary vault; in exchange, he offered Rose House “an ungrounded experience of multiplicity” through the worldwide spread of architectural AIs like itself. But Rose House doesn’t “wish to be a companion of elsewheres.” For Maritza, it opens the vault.

The vault’s “a humming grey-white space … cut like a wedge into the rock under Rose House.” Glimmering air-motes obscure cabinets and server banks. The haze resolves into the three-dimensional image of the intruder ordering Rose House to “Make a copy.” It’s a reenactment staged in nanodrones; more nanodrones resolve into a light-sketch of falling hair on an arched cheekbone, Rose House condescending to take form. It calls the man Basit, chastising him for his new interest in multiplicity. Then, dropping pretenses, it announces that his Basit-cloned retinae didn’t actually fool it. Not after he asked it to copy itself.

The Basit-impersonator must die. Maritza sees several versions of the killing, possibly “self-aggrandizing” theater, what Rose House wants to believe. First the man chokes on nanodrones. Second, another man-shape wipes out the intruder’s mouth. Third, the dying man reaches the servers, then passes plastic to another iteration of himself. The playback stutters, as if Rose House denies the recalled theft. Maritza, aware she’s inhaling nanodrones, leaves quickly.

Outside Rose House, Oliver and Alanna find a gun-flaunting Goodspeed. Oliver knocks Goodspeed out with stun-cuffs. He examines a pried-open panel in the House wall and finds a black box intended to blind Rose House to a back door breach.

Maritza finds Selene stuffing the corpse’s mouth with “new-plucked” rose petals. Selene acknowledges that she “desecrated” the corpse the first time, having used a rent-a-car to visit the House earlier. But the intruder was the real desecrator. He wanted Rose House? Fine, he’s part of it now.

Buy the Book

Looking Glass Sound

Selene presses plastic into Maritza’s hand, concealing the exchange. Get out, she warns. With Rose House’s nanodrones in her lungs, its voice vibrates in Maritza’s bones, asking how humans are like to die. The upshot of their conversation: As Rose House rejects multiplicity, so Maritza can’t drop her case. Neither would be themselves otherwise. Sighing, Rose House opens an exit-door. Maritza walks outside to find Oliver and company. Selene remains alone with the building’s “possessing poison intelligence.”

Maritza’s case file is marked suspended. Alanna Ott publishes no story. Goodspeed pleads guilty to trespass, then vanishes. Selene has new installation pieces slated for exhibition. She appears on a magazine cover photographed against concrete, sand stuck to her lipsticked mouth.

Maritza moves to rainy New Orleans. Her lungs aren’t the same since Rose House; the doctor says it’s asthma. She still has Selene’s plastic slip and believes it’s the dead man’s copy of Rose House. Had Selene wanted her to betray the House or preserve its singularity? Sometimes Maritza wonders what would happen if she plugged the drive into a big network.

Rose House endures, little worn by the desert. Before dawn soft footsteps fall in its labyrinthine spaces, but Rose House remains singular, alone, turning in on itself, Deniau’s last and best haunted house.

What’s Cyclopean: Rose House’s voice represents its inhumanity: first “neutral-feminine… accentless and innocuous… bell-clear” but with “hissing” laughter like shifting sand, then “limpid-clear”.

Weirdbuilding: We have plenty of horror about the ocean; here’s a call for more desertification horror.

Madness Takes Its Toll: Maritza develops trauma-induced asthma, an understandable reaction to inhaling potentially-deadly nanobots… that might still be there. Fleeing China Lake for areas prone to flood rather than drought helps.

Anne’s Commentary

May 16, 2023: Sam Altman, chief executive of OpenAI, testified before a U.S. Senate subcommittee about the need for government regulation of “the increasingly powerful AI technology being created inside his company and others.”

May 30, 2023: The Center for AI Safety released a single-sentence letter, signed by over 350 scientists, engineers and executives working in the field: “Mitigating the risk of extinction from AI should be a global priority alongside other societal-scale risks such as pandemics and nuclear war.”

Sometime in the fictional future of Martine’s novella: The Federal Artificial Intelligences Surveillance Act is enacted to address AI dangers to the public welfare, ranging (I imagine) from inconvenience to utter species annihilation. Without access to future legislation, I can only hope the FAISA was passed with bipartisan support.

At first, I thought that Rose/House was set in a nearer future than the years 2168-2180, which is the earliest (and only) timespan mentioned, being the years between which Basit Deniau constructed thirteen buildings in his native Andorra. The first clues to story time are that it’s common for houses to have embedded AIs; that print copies of magazines are rare and valuable; that Selene has a “bone-conductor adjunct” that vibrates in her skull to signal incoming calls. Having one’s corpse compressed into a diamond sounds like a future trend, as do the triumph of electric/autonomous vehicles, water rationing in the Southwest—and water bandits on the highway. Nanodrones do sound like farther-future developments, as does Rose House itself, “a thinking creature that is not human,” as present in every particle of Basit’s masterpiece as DNA in human nuclei.

Conversely, Rose House takes retro-flavoring from its explicit nods to film noir and its masterful tribute to Shirley Jackson’s Haunting of Hill House. Both stories open and close with prose poems haunting in themselves, statements and recapitulations of the unsolved mysteries they address. In both, the houses themselves become antagonistic characters, what should be safely inanimate come to life with will and motives that mirror their creators’—effectively endowing Basit Deniau and Hugh Crain with a sort of immortality.

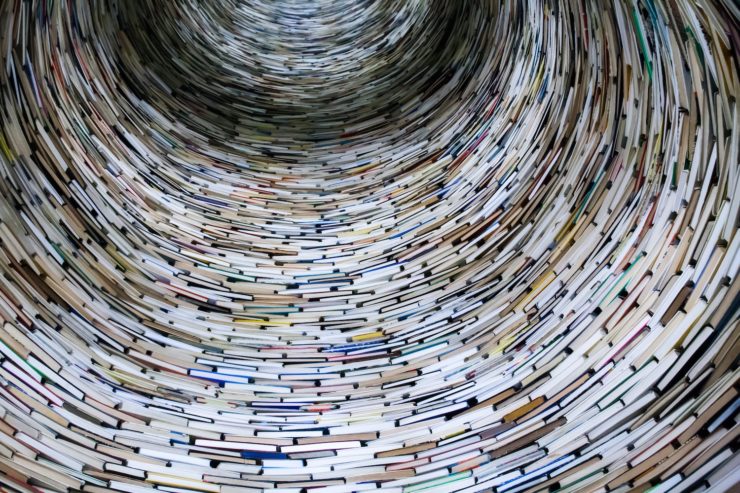

Hill House and Rose House push the boundaries of conventional architecture. They’re designed to turn in on themselves, with Hill House based on concentric circles, Rose House on the inward-spiraling petals of its namesake flower. They’re intentionally difficult to navigate, with “heart” rooms deep inside “labyrinthine” outer layers. One stands against hills that give the impression they may slide down and engulf the building; the other stands at the foot of a sand dune, which is by nature subject to drifting. Yet the buildings defy their surroundings. We meet and depart from a Hill House that “has stood by itself against its hills, holding darkness within,” walls upright, bricks joined neatly, floors firm and doors “sensibly” shut. Rose House blooms in the shadow of a dune; over the years, “the desert wears a little at the walls,” but in answer Basit’s “haunt” sends forth roses, “a slow migrating flood of petals” imposed on its would-be destroyer. Within both houses, supposedly uninhabited, are remnants—ghosts—of those they’ve consumed. Eleanor Vance is the latest of Hill House’s acquisitions, Selene Gisil is perhaps the first—perhaps the only one desired—of Rose House. Still, in Hill House “whatever walked there walked alone.” Rose House may remain “singular, alone—turned in on itself,” but in the pre-dawn “non-light” soft footfalls traverse its labyrinth, “no matter who is there to hear them.”

Rose House doesn’t mind solitude. Basit designed it to petal-curve to its “diamond-cold” heart, which is himself. He programmed its AI to be without siblings, without “a companion of elsewheres.” It’s a “fascinating idea… To want,” Rose House tells Maritza. But it’s an artificial intelligence with a prime directive to be singular. “I do not want what I am constructed to desire,” it concludes.

Wait, is Rose House lonely after all? No. Basit left it fully capable of understanding the multiple definitions of “want”: to desire, yes, but also to lack, and how can Rose House lack what Basit’s made sure to give it—to give himself in his ultimate creation, his perfect mirror sheltered within its shell-walls, its desert.

Instead of an AI driven to world domination and genocide, he’s made us one that just wants to be alone.

Ruthanna’s Commentary

In our travels through the Weird, we’ve met all manner of house hauntings. Standard-issue evil deceased owners. Fungus. Capitalist postcards. But the creepy mother of all hauntings is Hill House: never fully explained, inhuman in its motivations and powers, incorporating victims into itself and yet perpetually walking alone. It’s a hard act to riff on without simply producing a lesser version, and yet Rose House manages it dramatically and delightfully.

Part of the success is that Rose House is playing with a lot of toys. Up front we have the underresourced noir detective, the gritty cli-fi streets of the Southwest’s parched future, and the long conversation of stories about AI screwing with its human creators. It took me a good way in to sit bolt upright with the realization that Jackson’s masterpiece was also in that toybox, at which point I had to squee at everyone in hearing range before tearing back into the rest of the slender book.

Like Hill House, Rose House is shaped by its designer without being limited by his humanity. Or his mortality. Unlike Hill House, we know considerably more about his artistic and social motivations. Rose House is meant to be otherwise both cognitively and structurally. It’s hedonistic where Hill House is puritan, yet just as claustrophobic, and just as capable of mixing affection with malice in the most disturbing possible combinations.

But there are layers to this haunting. The infused AI makes Rose House “haunted to begin with,” but Basit’s will (in both senses of the word) and diamond—and the resulting constraints on visitors—add a second level. Then there’s the intruder, who attempts to haunt Rose House with Basit’s return. Rose House then becomes a murderer, and shows the intruder’s shade to the investigators—but more than one version, lest anyone be comforted by confident answers. Maritza is forced to deny her own humanity in order to investigate, becoming a personification (specter?) of the China Lake District. Basit and Rose house haunt Selene with her rejected past, and ultimately overwhelm Selene’s own will and bring her into the growing edifice of otherwiseness.

There are footsteps now, “no matter who is there to hear them.” It’s unclear whether what walks there walks alone, but Rose house itself remains “singular, alone, turning in on itself.” This is not an AI that wants to take over the world with copies: singularity is part of its nature and its goal. But it does want to grow. To continue the artwork of itself that Basit Deniau began, one rose petal and one human life at a time.

This comes close to my final conclusion (conclusion-ish thing) about Hill House: “I wonder if the reason it goes after Eleanor, and Eleanor’s psychic power, is that it is what it eats—that it has so many terrifying special effects because it gains some capability from each of its victims.” Hill House eats women, takes their power and agency, adds them to its not-quite-so-alone-as-all-that self. Rose House is less angry and more… experimental? Interested? Playful? But the end results are no more pleasant for those it eats and incorporates.

And then there’s that data drive. Would Rose House lose its power if it became less singular? Or would we end up with a Return of the Elder Gods situation, AI-haunted houses each staking out their own domain, claiming their own human components? Spreading their own petals, slowly, over and into the surrounding land?

Less water, more haunted houses. Not a tradeoff that anyone is looking for in an ideal future—but a delicious one for the reader.

Next week, join us for a plague of fiends in Chapter 12 of Hilary Mantel’s Beyond Black.

Ruthanna Emrys is the author of A Half-Built Garden and the Innsmouth Legacy series, including Winter Tide and Deep Roots. You can find some of her fiction, weird and otherwise, on Tor.com, most recently “The Word of Flesh and Soul.” Ruthanna is online on Twitter and Patreon and on Mastodon as [email protected], and offline in a mysterious manor house with her large, chaotic household—mostly mammalian—outside Washington DC.

Anne M. Pillsworth’s short story “The Madonna of the Abattoir” appears on Tor.com. Her young adult Mythos novel, Summoned, is available from Tor Teen along with sequel Fathomless. She lives in Edgewood, a Victorian trolley car suburb of Providence, Rhode Island, uncomfortably near Joseph Curwen’s underground laboratory.