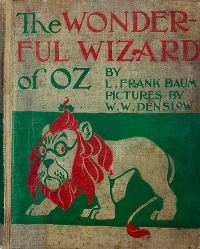

The Wonderful Wizard of Oz appeared a little over a century ago, spawning at least 200 sequels (some authorized, some not, some with marvelous titles like The Haunted Hot-Tub of Oz); a little film you might have heard of; several other films of greater or lesser inspiration; a couple of musicals; plenty of comics; a delightful collection of toys, calendars, games and more.

And still, more people are familiar with the movie than with the book, which is a pity, since the original book and series are among the most original works in American literature. And phenomenally lucrative, for everyone except L. Frank Baum, the creator, helping to establish the commercially successful genres of fantasy and children’s literature. The books also inadvertently helped to spawn the production of long running fantasy series—inadvertently, because Baum had no plans to create a series when he sat down to write the first book. (This helps account for the myriad inconsistencies that pop up in later books.)

So what’s in the book, you might ask?

You probably know the story: small girl gets snatched from the dull, grey, poverty stricken prairies of Kansas (Baum may actually have had the Dakotas in mind) to a magical land of color and wealth and above all, plentiful food, where she meets three magical companions: the Scarecrow, the Tin Woodman, and the talking Cowardly Lion. To return home, she must gain the help of the Wizard of Oz, which he will give only if she kills the Wicked Witch of the West. She does so, only to find that Oz cannot help her. She takes a second, somewhat anticlimactic journey to another witch, and finds that she only needs to click her heels and the shoes she is wearing will take her home.

It’s a classic Quest story, clearly influenced by Grimm’s fairy tales, where the hero receives aid from talking animals or magical friends after receiving some kindness from the hero. But right from this first book Baum begins to subvert the old tales. Most of the fairy tale helpers Dorothy meets along the way are neither wise nor able to tell her how to destroy her enemy. Although they join her quest, they do so for their own goals—the brain, the heart, and courage. And while they do protect her, killing multiple animals as they do, she must rescue them from the Wicked Witch, unlike in Grimm’s tales, where after their original rescues, the magical animals and helpers generally remain on the sidelines, but safe.

And, of course, in a major twist, Dorothy is just an ordinary young farm girl, not a princess, without even the comfortable upper class confidence of Alice in Wonderland, and rather than become a princess or queen, her reward is a safe return to her barren Kansas home. A few books later, Dorothy would become a princess, and Oz a comfortable socialist paradise ruled by women—about as subversive as an early 20th century American kids book could get—and while A Wonderful Wizard of Oz is not quite there yet, glimmers of that direction are there.

Nonetheless, rereading this book after reading the other Oz books can be a bit startling. Certainly, some of the best known features of Oz are already present: the talking animals, the strange concern for the pain and suffering of insects, the trend towards human vegetarianism (Dorothy eats only bread, fruits and nuts on her journey, even after the Lion offers the possibility of fresh venison), the puns, the fantastically improbable characters, the wealth and abundance, and the division into different territories each marked by color (blue for the Munchkins, Yellow for the Winkies, and so on.)

But the rest is decidedly different. Not merely the absence of Ozma (the later ruler of Oz) but the presence of two elements later removed from the world of Oz—money and death. Children pay for green lemonade with green pennies. And while in later books Baum would claim that no one, human or animal, could age or die in Oz, in this book the death toll is astounding, even apart from the Wicked Witches: several wolves, a wildcat, a giant spider, bees, birds, and—offscreen—the Tin Woodman’s parents and whatever the Cowardly Lion is eating for dinner that the Tin Woodman does not want to know about. And before most of these deaths are dismissed as, “oh, well, they were just animals,” bear in mind that these are talking animals, and the Lion, at least, is accepted as a complete equal.

But perhaps the greatest difference is Baum’s focus on the power of the ordinary over the magical here, and the way ordinary things—bran and needles—can be substitutes for genuinely magical items, like brains for a living Scarecrow. The Wicked Witches are destroyed by the most ordinary of things: a flimsy one room claim shanty from Kansas and plain water. The brains, heart and courage the Wizard gives Dorothy’s companions are all things that Dorothy might have found anywhere in a Kansas store. (Well. She might have had to sew the silk for the sawdust heart together.) The Wizard uses a balloon, not a spell, to escape. And although occasionally Dorothy and her gang resort to magic to escape various perils (summoning the Winged Monkeys as a kind of Ozian taxi service), for the most part, they use ordinary tools: logs, axes, hastily assembled log rafts, and so on.

This elevation of the ordinary would later be changed. But in this book, Baum was content to reassure readers that magic wasn’t everything, or necessary for happiness.

I’m leaving out several bits that make this book wonderful: the way the text bursts with color, the way the tale is structured to allow for perfect bedtime reading (nearly every chapter presents a small mini story, with a climax and happy resolution, and the book reads wonderfully out loud), the tiny details (the green hen laying a green egg) that make the book come alive, the magic of reading about a talking Scarecrow and a man made from tin. (Although I’ve often wondered—where do all of those tears the Tin Woodman is continually weeping and rusting over come from, since supposedly he never eats nor drinks?)

Oz was supposed to end there, but Baum found himself chronically short of money, and continuously turned to his one reliable cash cow, Oz, whenever he felt financially desperate, which was most of the time. In upcoming weeks, I’ll be looking at the slow transformation of Oz from the land of pure marvel to early feminist utopia. And possibly examining the puns. Oh, the puns. But we’ll save that pain for now.

Mari Ness lives in central Florida, near a large lake infested with alligators, who so far have refused to confirm that they have the ability to speak. When not thinking about Oz, she spends her time futilely trying to convince her cats that the laptop is not a cat bed. She keeps a disorganized blog at mariness.livejournal.com.