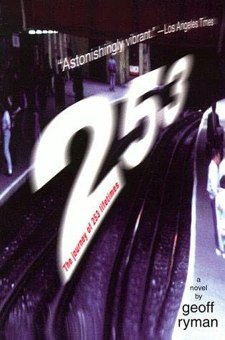

253 is one of those books that ought to be gimmicky but isn’t. It’s 253 descriptions of 253 people on a London underground train, all described in 253 words each. It was originally published online in the days before there was really a proper web in the early nineties—I remember seeing it all in grey, it was one of the first things I actually looked at online. It’s still online with rather better graphics. But I recommend you pick up the Philip K. Dick Award-winning “print remix” and read it all in one go, or if you do read it online read it as a novel, as one whole thing, rather than skipping about in it as the online format encourages. When I did that, it did seem like a gimmick. Reading all of it, one person after the next, all through the train to the inevitable ending, it becomes something more.

This isn’t really science fiction or fantasy. There’s nothing overtly fantastical in it, except for the footnote in which the ghost of William Blake gets out in Lambeth, which is in my opinion worth the price of the book all by itself. But reading it, reading all of it, is a deeply science fictional experience all the same. It’s like John Varley’s Manhattan Phone Book (Abridged) and not like anything else at all.

There are closely observed people and inevitability. There are strange connections, coincidences, last minute escapes, sidesplitting comedy and heartbreaking tragedy. You meet these people for a very short time, but you see right inside them. It’s like the condensed experience of reading an ordinary novel—no, condensed isn’t the right metaphor. It’s like the exploded experience—this is like an exploded diagram of a novel, with all the experience of reading a novel combined with seeing it simultaneously in exploded diagram form.

To give an example, there’s a man who sells the Big Issue at Waterloo—a homeless man, who is on the train, and who is pursuing relationships with a number of different women on the train, to whom he has told different stories about his background. We see him after we have seen them, spread throughout the book, and until we do meet him we can’t be sure that they are all thinking about the same man, although we must suspect. The book is full of tangles like this. Because of the exploded diagram nature the experience of reading it feels a lot more like playing God than the normal experience of reading a novel, where you have a story and follow a limited set of characters. Here you have everyone and they all have a story and a surprising number of them connect.

It’s funny, of course, and it’s tragic, and it’s a farce in the way that life so often is. And although it is one person after another, it is paced like a novel, there are revelations, there’s foreshadowing, there’s a beginning and very definitely an end.

I wouldn’t have read this even once if I didn’t already like Ryman’s more conventional work a great deal. I found it very strange at first, but I like it and I keep coming back to it, to these beautifully observed and imagined people, this intersection of lives. It’s surprisingly effective and surprisingly moving. Also, there is an awesome footnote about William Blake coming out of the train in Lambeth North and seeing 1995 and thinking it is a vision, recognising London voices and seeing that he is remembered.

Jo Walton is a science fiction and fantasy writer. She’s published two poetry collections and nine novels, most recently Among Others, and if you liked this post you will like it. She reads a lot, and blogs about it here regularly. She comes from Wales but lives in Montreal where the food and books are more varied.