In this bi-weekly series reviewing classic science fiction and fantasy books, Alan Brown looks at the front lines and frontiers of the field; books about soldiers and spacers, scientists and engineers, explorers and adventurers. Stories full of what Shakespeare used to refer to as “alarums and excursions”: battles, chases, clashes, and the stuff of excitement.

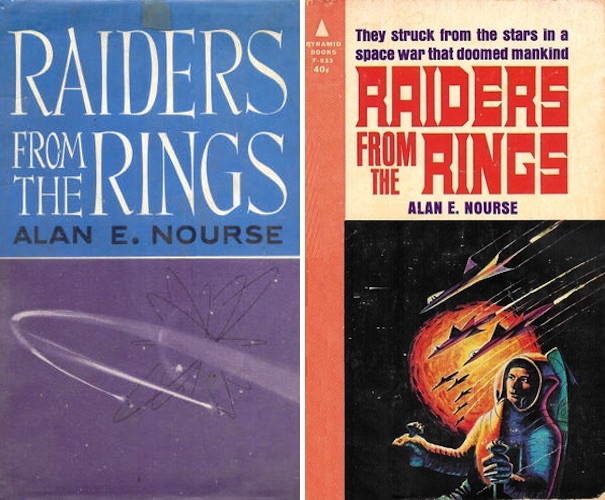

Sometimes, you revisit an old favorite book from your childhood, and it feels comfortable and familiar. Other times, you put it down after re-reading, and ask, “Is that the same book I read all those years ago?” For me, one such book is Raiders from the Rings by Alan E. Nourse. I remembered it for the action, the exciting depictions of dodging asteroids while pursued by hostile forces. But while I did find that this time around, I also found a book with elements that reminded me of Margaret Atwood’s The Handmaid’s Tale. Which raised a question in my mind: how did this troubling subject matter end up in a 1960s juvenile novel?

I discovered the works of Alan E. Nourse in the library during my youth for one simple reason: In the juvenile science fiction section, his works were immediately adjacent to those of Andre Norton. Norton was a favorite of my older brother, whose books I often borrowed after he was finished. I was also immediately impressed that Nourse spelled his first name correctly, not with that extra ‘l’—or worse, an ‘e’ instead of the middle ‘a,’ which so many people added to my own name. As I recollect, there were three books by Nourse in the library: The Universe Between, a mind-bending tale about the discovery of a parallel universe with a fourth physical dimension; Tiger by the Tail, a collection of short stories; and Raiders from the Rings, a rip-snorting adventure story that I checked out many times.

About the Author

Alan E. Nourse (1928-1992) was a physician who also had a long and productive writing career. He primarily wrote science fiction, which included a number of juvenile novels. He also wrote mainstream fiction, non-fiction books on science and medical issues, and penned a column on medical issues that appeared in Good Housekeeping magazine. While his work was well crafted and he was respected by his peers, he never received a Hugo or Nebula award. He wrote Raiders from the Rings in 1962.

In addition to his novels, Nourse also published many excellent stories that are well worth reading. One that has stuck in my head over the years is “The Coffin Cure,” in which an effort to cure the common cold becomes an object lesson on the danger of rushing through the research process, and the unintended consequences that may result. Like many authors of his time, some of his work is out of copyright, and available for reading on the internet (see here for work available on Project Gutenberg).

Ironically, Nourse’s greatest claim to fame in the science fiction world may be the attachment of a title to one of his books to a movie. Ridley Scott and his team were beginning work on a film based on Phillip K. Dick’s Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?, but the original title was not felt to be accessible to moviegoers. The screenwriter came across a treatment of a novel by Nourse called The Bladerunner, and gained permission to attach that title to his adaptation of the Dick story.

Asteroid Civilizations

The asteroid belt, a collection of small objects and planetoids that orbits between Mars and Jupiter, has always fascinated me. I have early memories of a Tom Corbett Space Cadet tale (I think it was in the form of View-Master reels) where the protagonists discovered that the asteroids were the remnants of an ancient planet that was destroyed, and found evidence of an ancient civilization. And of course, more than one science fiction author has portrayed a society based in the asteroids. Larry Niven’s Known Space series portrayed Belters as fierce individualists and independent miners. Ben Bova’s Asteroid Wars books depicted industrialists clashing over the resources of the asteroid belt. And Isaac Asimov’s Lucky Star and the Pirates of the Asteroids casts the belt as the home of criminal gangs. More recently, James S. A. Corey’s Expanse series also features inhabitants of the belt as major players in the solar system’s conflicts.

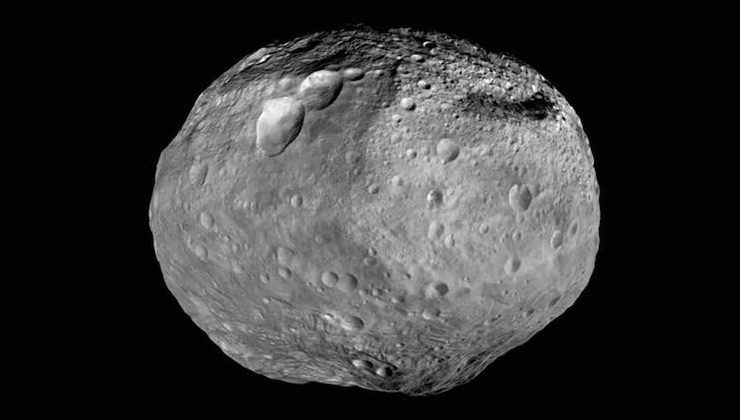

Star Wars fans, when asteroids are mentioned, immediately think of the Millennium Falcon in The Empire Strikes Back, twisting its way through tightly-grouped rocks while the TIE Fighters crash and burn on every side. But that cinematic portrayal of asteroids is as fanciful as their appearance in Antoine de Saint-Exupéry’s The Little Prince, where the protagonist lives alone on an asteroid that sports an atmosphere, volcanos, and a variety of plants.

In actuality, the asteroid belt is neither dense, nor is it well suited for a single, cohesive culture. Asteroids are numerous, but scattered thinly over a wide area. In an article first published in Galaxy in 1974, which I found in the Ace Books collection A Step Farther Out, “Those Pesky Belters and Their Torchships,” Jerry Pournelle pointed out that, while they share a similar orbit, the distances between the major asteroids make them, in many cases, further from each other in terms of fuel expenditures than they are from the major planets (an expansion of those ideas can be found here, in an article by Winchell Chung). Pournelle suggested that if a cohesive society built around the exploitation of small worlds were to form, it would be more probable in the moons of Jupiter or Saturn than in the asteroid belt.

While science fiction stories may not have gotten all the details right, however, the asteroid belt, assuming that humanity moves into space, will likely be among the first resources to be exploited. There are a variety of minerals and ice just waiting to be harvested, without the need to enter a gravity well to access them. Regardless of how the efforts are organized, extensive human activity in the asteroid belt will be an integral part of any move out into the solar system. As Robert A. Heinlein famously said, “Once you get to earth orbit, you’re halfway to anywhere in the solar system.”

Raiders from the Rings

The book begins with a prologue, where we follow a team of raiders boarding an Earth ship. They are there to rescue a woman, referred to as a mauki, who is singing a lament that has the crew transfixed. The Earth crew has murdered her five-year-old child, but she will not let the raiders destroy them. She says they acted out of fear, and she wants them to live to bring word of her song back to Earth. The naming of the woman as a “mauki” always intrigued me, but I could find no previous reference for that word, other than its use as the name of a slave in a Jack London story. It may be that Nourse created the term for the novel.

The book begins with a prologue, where we follow a team of raiders boarding an Earth ship. They are there to rescue a woman, referred to as a mauki, who is singing a lament that has the crew transfixed. The Earth crew has murdered her five-year-old child, but she will not let the raiders destroy them. She says they acted out of fear, and she wants them to live to bring word of her song back to Earth. The naming of the woman as a “mauki” always intrigued me, but I could find no previous reference for that word, other than its use as the name of a slave in a Jack London story. It may be that Nourse created the term for the novel.

We then join eighteen-year-old Ben Trefon as he lands his personal ship on Mars to visit his father at the family home. Ben’s family is among the leading families among the raiders, exiled from Earth, who live throughout the solar system. He is excited about participating in his first raid on Earth, but shocked to find that his father, Ivan, not only wants Ben to sit out the raid, but has gone to the raider Council to get the raid cancelled altogether. The old man has a feeling that something is terribly wrong, and that the raid may lead to disaster. We learn that these raids have two purposes. The first is to seize the food the raiders need to survive. The second is to capture women.

It turns out that exposure to the radiation of space precludes women from having female babies. Thus, in order to perpetuate the survival of their people, the raiders regularly kidnap women from Earth. Bride kidnapping is something that has occurred throughout history, and unfortunately continues to this day. Kidnapping to bring more genetic diversity into a tribe was a past practice of some Native American tribes, and this may be where Nourse got the idea. I had not remembered this aspect of the book, and with the generally prudish approach that juvenile publishers took in the era in which it was published, I am surprised it was deemed appropriate for a novel targeted toward young people. As a young reader, I had very little exposure to hardship or sorrow, and I missed the implications of this practice; in fact, I thought being kidnapped by space pirates sounded exciting. As an adult, however, I could not ignore it, and it evoked reactions similar to those I felt when I read The Handmaid’s Tale. The fact that the raider society was based on the exploitation of unwilling women was a sticking point I could not get past or dismiss, and that context made re-reading the book an unpleasant experience, at times.

In terms of the plot, the raid goes on as scheduled, and Nourse does a thrilling job of describing how it is carried out. The raiders meet more resistance than they expected, and Ben barely escapes with a captive girl on his shoulders, only to find her brother aboard his ship with a gun. He desperately launches the ship into space to throw off the boy’s aim, and soon finds himself with one too many captives. As they leave Earth, he finds that the pair, Tom and Joyce Barron, are full of all sorts of nasty ideas regarding raider society involving tortured captives and the breeding of evil armies of mutants. They also dispel Ben of many false notions he’d held about Earth culture. From the perspective of Earth, the raiders are traitors, descendants of military men who disobeyed the orders of their nations. But the raiders insist on the fact that those orders were to rain nuclear weapons onto Earth, and see their actions as having saved the planet. Somewhat more quickly than seems reasonable, the three teens see through the propaganda of their elders and form a friendship.

That friendship is soon put to a test when Ivan Trefon’s fears prove well-founded, and Earth launches a huge warfleet into space. Ben returns to Mars only to find that the Earth forces have killed his father and everyone in his home. He finds two items that his father wanted him to have, but never explained. One is a mysterious egg-like object, and the other is the tape of a mauki song in a mysterious language. Ben checks other homes on Mars, finding them destroyed as well, and decides to head out to the asteroids, where some raiders should have survived. On the way, they are shadowed by an elusive phantom ship, and soon find themselves attacked and crippled by Earth forces.

The three land on an asteroid to make repairs. Ben and Tom work around the clock to fix the ship, while Joyce explores the asteroid to avoid boredom (the idea that a woman could potentially help with the repairs apparently eludes all of them). Joyce comes back to the ship in a panic, having seen what she thinks are the evil mutants from Earth propaganda. She and the boys go out to investigate, and make contact with an alien race—a race that knows of Ben through his father, and those mysterious objects Ben gathered at his home prove to be quite important. These aliens have been monitoring mankind from afar, and have advice on how the conflict could be ended.

But first, Ben, Tom, and Joyce must find their way to the raiders’ headquarters on Asteroid Central. And here, Nourse gives us a thrilling chase through tightly-packed asteroids that could be torn right out of a lurid pulp—but he does it in a way that is perfectly plausible. To protect their headquarters from both missile attacks and invaders, the raiders have surrounded it with a cloud of re-positioned asteroids in a variety of orbits. So, we get the thrill of the chase without having to check scientific fact at the door.

In the end, the songs of the mauki prove pivotal. This aspect of the book might stretch believability for some readers, but I have spent more than a few evenings in Irish pubs, and have heard sean-nós, or “old style,” singers quiet a boisterous crowd and hold them entranced until the final note fades away. The old laments, and the sound of a solitary human voice, often have a power that must be heard to be believed.

That said, I will leave the other details of the plot and ending alone at this point, in order to prevent spoiling anything for those who might decide to read the book.

Final Thoughts

Raiders from the Rings was a quick read, full of action and adventure. I can see why it appealed to me as a youth. The book is a competently executed juvenile novel, which pays attention to science along the way. I enjoyed reading about teenagers who were capable of solving problems whose solutions had eluded adults for generations. And who wouldn’t want to have their own personal spaceship that can zip around the solar system as easily as the family SUV drives around town?

The concept of bride kidnapping mars what would have otherwise been a fun adventure, and the attitudes of the boys toward Joyce are enough to set modern teeth on edge. There is nothing wrong with an author putting a problematic issue at the center of a story, but once they have done so, it feels wrong to utterly ignore all the implications of that issue. For example, Ben reads like a happy, privileged, well-adjusted suburban teenager—not someone from a fugitive society raised by a kidnapped mother. And he doesn’t question the morality of his actions when he kidnaps Joyce, which makes me think quite a bit less of him and his character. The raiders owe their entire existence to theft and kidnapping. While they began with the best of intentions by preventing nuclear war, it seems to me that their society has a moral rot at its core, which is not sufficiently addressed anywhere in the novel.

Because of those issues, I would not recommend this particular novel to a new reader without caveats. But I do wholeheartedly recommend that people seek out and explore the works of Alan E. Nourse in general. He is an excellent author, who deserves to be more widely read and remembered by the science fiction community. As I pointed out above, many of his works are available via Project Gutenberg, and can be found here.

And now it’s time for you to chime in: Have you read Raiders from the Rings, or the other works by Nourse? If so, what did you think? And what are your thoughts on how fiction targeted at young readers should grapple with troublesome issues?

Alan Brown has been a science fiction fan for over five decades, especially fiction that deals with science, military matters, exploration and adventure.