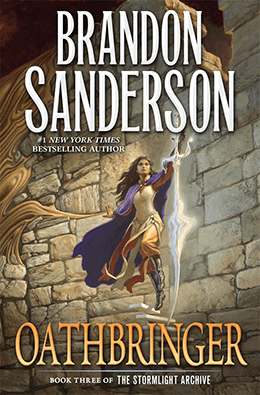

Start reading Oathbringer, the new volume of Brandon Sanderson’s Stormlight Archive epic, right now. For free!

Tor.com is serializing the much-awaited third volume in the Stormlight Archive series every Tuesday until the novel’s November 14, 2017 release date.

Every installment is collected here in the Oathbringer index.

Need a refresher on the Stormlight Archive before beginning Oathbringer? Here’s a summary of what happened in Book 1: The Way of Kings and Book 2: Words of Radiance.

Spoiler warning: Comments will contain spoilers for previous Stormlight books, other works that take place in Sanderson’s cosmere (Elantris, Mistborn, Warbreaker, etc.), and the available chapters of Oathbringer, along with speculation regarding the chapters yet to come.

Chapter 19

The Subtle Art of Diplomacy

THIRTY-ONE YEARS AGO

A candle flickered on the table, and Dalinar lit the end of his napkin in it, sending a small braid of pungent smoke into the air. Stupid decorative candles. What was the point? Looking pretty? Didn’t they use spheres because they were better than candles for light?

At a glare from Gavilar, Dalinar stopped burning his napkin and leaned back, nursing a mug of deep violet wine. The kind you could smell from across the room, potent and flavorful. A feast hall spread before him, dozens of tables set on the floor of the large stone room. The place was far too warm, and sweat prickled on his arms and forehead. Too many candles maybe.

Outside the feast hall, a storm raged like a madman who’d been locked away, impotent and ignored.

“But how do you deal with highstorms, Brightlord?” Toh said to Gavilar. The tall, blond-haired Westerner sat with them at the high table.

“Good planning keeps an army from needing to be out during a storm except in rare situations,” Gavilar explained. “Holdings are common in Alethkar. If a campaign takes longer than anticipated, we can split the army and retreat back to a number of these towns for shelter.”

“And if you’re in the middle of a siege?” Toh asked.

“Sieges are rare out here, Brightlord Toh,” Gavilar said, chuckling.

“Surely there are cities with fortifications,” Toh said. “Your famed Kholinar has majestic walls, does it not?” The Westerner had a thick accent and spoke in a clipped, annoying way. Sounded silly.

“You’re forgetting about Soulcasters,” Gavilar said. “Yes, sieges happen now and then, but it’s very hard to starve out a city’s soldiers while there are Soulcasters and emeralds to make food. Instead we usually break down the walls quickly, or—more commonly—we seize the high ground and use that vantage to pound the city for a while.”

Toh nodded, seeming fascinated. “Soulcasters. We have not these things in Rira or Iri. Fascinating, fascinating… And so many Shards here. Perhaps half the world’s wealth of Blades and Plates, all contained in Vorin kingdoms. The Heralds themselves favor you.”

Dalinar took a long pull on his wine. Outside, thunder shook the bunker. The highstorm was in full force now.

Inside, servants brought out slabs of pork and lanka claws for the men, cooked in a savory broth. The women dined elsewhere, including, he’d heard, Toh’s sister. Dalinar hadn’t met her yet. The two Western lighteyes had arrived barely an hour before the storm hit.

The hall soon echoed with the sounds of people chatting. Dalinar tore into his lanka claws, cracking them with the bottom of his mug and biting out the meat. This feast seemed too polite. Where was the music, the laughter? The women? Eating in separate rooms?

Life had been different these last few years of conquest. The final four highprinces stood firm in their unified front. The once-frantic fighting had stalled. More and more of Gavilar’s time was required by the administration of his kingdom—which was half as big as they wanted it to be, but still demanding.

Politics. Gavilar and Sadeas didn’t make Dalinar play at it too often, but he still had to sit at feasts like this one, rather than dining with his men. He sucked on a claw, watching Gavilar talk to the foreigner. Storms. Gavilar actually looked regal, with his beard combed like that, glowing gemstones on his fingers. He wore a uniform of the newer style. Formal, rigid. Dalinar instead wore his skirtlike takama and an open overshirt that went down to midthigh, his chest bare.

Sadeas held court with a group of lesser lighteyes at a table across the hall. Every one of that group had been carefully chosen: men with uncertain loyalties. He’d talk, persuade, convince. And if he was worried, he’d find ways to eliminate them. Not with assassins, of course. They all found that sort of thing distasteful; it wasn’t the Alethi way. Instead, they’d maneuver the man into a duel with Dalinar, or would position him at the front of an assault. Ialai, Sadeas’s wife, spent an impressive amount of time cooking up new schemes for getting rid of problematic allies.

Dalinar finished the claws, then turned toward his pork, a succulent slab of meat swimming in gravy. The food was better at this feast. He just wished that he didn’t feel so useless here. Gavilar made alliances; Sadeas dealt with problems. Those two could treat a feast hall like a battlefield.

Dalinar reached to his side for his knife so he could cut the pork. Except the knife wasn’t there.

Damnation. He’d lent it to Teleb, hadn’t he? He stared down at the pork, smelling its peppery sauce, his mouth watering. He reached to eat with his fingers, then thought to look up. Everyone else was eating primly, with utensils. But the servers had forgotten to bring him a knife.

Damnation again. He sat back, wagging his mug for more wine. Nearby, Gavilar and that foreigner continued their chat.

“Your campaign here has been impressive, Brightlord Kholin,” Toh said. “One sees a glint of your ancestor in you, the great Sunmaker.”

“Hopefully,” Gavilar noted, “my accomplishments won’t be as ephemeral as his.”

“Ephemeral! He reforged Alethkar, Brightlord! You shouldn’t speak so of one like him. You’re his descendant, correct?”

“We all are,” Gavilar said. “House Kholin, House Sadeas… all ten princedoms. Their founders were his sons, you know. So yes, signs of his touch are here—yet his empire didn’t last even a single generation past his death. Leaves me wondering what was wrong with his vision, his planning, that his great empire broke apart so quickly.”

The storm rumbled. Dalinar tried to catch the attention of a servant to request a dinner knife, but they were too busy scuttling about, seeing to the needs of other demanding feastgoers.

He sighed, then stood—stretching—and walked to the door, holding his empty mug. Lost in thought, he threw aside the bar on the door, then shoved open the massive wooden construction and stepped outside.

A sheet of icy rain suddenly washed over his skin, and wind blasted him fiercely enough that he stumbled. The highstorm was at its raging height, lightning blasting down like vengeful attacks from the Heralds.

Dalinar struck out into the storm, his overshirt whipping about him. Gavilar talked more and more about things like legacy, the kingdom, responsibility. What had happened to the fun of the fight, to riding into battle laughing?

Thunder crashed, and the periodic strikes of lightning were barely enough to see by. Still, Dalinar knew his way around well enough. This was a highstorm waystop, a place built to house patrolling armies during storms. He and Gavilar had been positioned at this one for a good four months now, drawing tribute from the nearby farms and menacing House Evavakh from just inside its borders.

Dalinar found the particular bunker he was looking for and pounded on the door. No response. So he summoned his Shardblade, slid the tip between the double doors, and sliced the bar inside. He pushed open the door to find a group of wide-eyed armed men scrambling into defensive lines, surrounded by fearspren, weapons held in nervous grips.

“Teleb,” Dalinar said, standing in the doorway. “Did I lend you my belt knife? My favorite one, with the whitespine ivory on the grip?”

The tall soldier, who stood in the second rank of terrified men, gaped at him. “Uh… your knife, Brightlord?”

“Lost the thing somewhere,” Dalinar said. “I lent it to you, didn’t I?”

“I gave it back, sir,” Teleb said. “You used it to pry that splinter out of your saddle, remember?”

“Damnation. You’re right. What did I do with that blasted thing?” Dalinar left the doorway and strode back out into the storm.

Perhaps Dalinar’s worries had more to do with himself than they did Gavilar. The Kholin battles were so calculated these days—and these last months had been more about what happened off the battlefield than on it. It all seemed to leave Dalinar behind like the discarded shell of a cremling after it molted.

An explosive burst of wind drove him against the wall, and he stumbled, then stepped backward, driven by instincts he couldn’t define. A large boulder slammed into the wall, then bounced away. Dalinar glanced and saw something luminous in the distance: a gargantuan figure that moved on spindly glowing legs.

Dalinar stepped back up to the feast hall, gave the whatever-it-was a rude gesture, then pushed open the door—throwing aside two servants who had been holding it closed—and strode back in. Streaming with water, he walked up to the high table, where he flopped into his chair and set down his mug. Wonderful. Now he was wet and he still couldn’t eat his pork.

Everyone had gone silent. A sea of eyes stared at him.

“Brother?” Gavilar asked, the only sound in the room. “Is everything… all right?”

“Lost my storming knife,” Dalinar said. “Thought I’d left it in the other bunker.” He raised his mug and took a loud, lazy slurp of rainwater.

“Excuse me, Lord Gavilar,” Toh stammered. “I… I find myself in need of refreshment.” The blond-haired Westerner stood from his place, bowed, and retreated across the room to where a master-servant was administering drinks. His face seemed even paler than those folk normally were.

“What’s wrong with him?” Dalinar asked, scooting his chair closer to his brother.

“I assume,” Gavilar said, sounding amused, “that people he knows don’t casually go for strolls in highstorms.”

“Bah,” Dalinar said. “This is a fortified waystop, with walls and bunkers. We needn’t be scared of a little wind.”

“Toh thinks differently, I assure you.”

“You’re grinning.”

“You may have just proven in one moment, Dalinar, a point I’ve spent a half hour trying to make politically. Toh wonders if we’re strong enough to protect him.”

“Is that what the conversation was about?”

“Obliquely, yes.”

“Huh. Glad I could help.” Dalinar picked at a claw on Gavilar’s plate. “What does it take to get one of these fancy servants to get me a storming knife?”

“They’re master-servants, Dalinar,” his brother said, making a sign by raising his hand in a particular way. “The sign of need, remember?”

“No.”

“You really need to pay better attention,” Gavilar said. “We aren’t living in huts anymore.”

They’d never lived in huts. They were Kholin, heirs to one of the world’s great cities—even if Dalinar had never seen the place before his twelfth year. He didn’t like that Gavilar was buying into the story the rest of the kingdom told, the one that claimed their branch of the house had until recently been ruffians from the backwaters of their own princedom.

A gaggle of servants in black and white flocked to Gavilar, and he requested a new dining knife for Dalinar. As they split to run the errand, the doors to the women’s feast hall opened, and a figure slipped in.

Dalinar’s breath caught. Navani’s hair glowed with the tiny rubies she’d woven into it, a color matched by her pendant and bracelet. Her face a sultry tan, her hair Alethi jet black, her red-lipped smile so knowing and clever. And a figure… a figure to make a man weep for desire.

His brother’s wife.

Dalinar steeled himself and raised his arm in a gesture like the one Gavilar had made. A serving man stepped up with a springy gait. “Brightlord,” he said, “I will see to your desires of course, though you might wish to know that the sign is off. If you’ll allow me to demonstrate—”

Dalinar made a rude gesture. “Is this better?”

“Uh…”

“Wine,” Dalinar said, wagging his mug. “Violet. Enough to fill this three times at least.”

“And what vintage would you like, Brightlord?”

He eyed Navani. “Whichever one is closest.”

Navani slipped between tables, followed by the squatter form of Ialai Sadeas. Neither seemed to care that they were the only lighteyed women in the room.

“What happened to the emissary?” Navani said as she arrived. She slid between Dalinar and Gavilar as a servant brought her a chair.

“Dalinar scared him off,” Gavilar said.

The scent of her perfume was heady. Dalinar scooted his chair to the side and set his face. Be firm, don’t let her know how she warmed him, brought him to life like nothing else but battle.

Ialai pulled a chair over for herself, and a servant brought Dalinar’s wine. He took a long, calming drink straight from the jug.

“We’ve been assessing the sister,” Ialai said, leaning in from Gavilar’s other side. “She’s a touch vapid—”

“A touch?” Navani asked.

“—but I’m reasonably sure she’s being honest.”

“The brother seems the same,” Gavilar said, rubbing his chin and inspecting Toh, who was nursing a drink near the bar. “Innocent, wide-eyed. I think he’s genuine though.”

“He’s a sycophant,” Dalinar said with a grunt.

“He’s a man without a home, Dalinar,” Ialai said. “No loyalty, at the mercy of those who take him in. And he has only one piece he can play to secure his future.”

Shardplate.

Taken from his homeland of Rira and brought east, as far as Toh could get from his kinsmen—who were reportedly outraged to find such a precious heirloom stolen.

“He doesn’t have the armor with him,” Gavilar said. “He’s at least smart enough not to carry it. He’ll want assurances before giving it to us. Powerful assurances.”

“Look how he stares at Dalinar,” Navani said. “You impressed him.” She cocked her head. “Are you wet?”

Dalinar ran his hand through his hair. Storms. He hadn’t been embarrassed to stare down the crowd in the room, but before her he found himself blushing.

Gavilar laughed. “He went for a stroll.”

“You’re kidding,” Ialai said, scooting over as Sadeas joined them at the high table. The bulbous-faced man settled down on her chair with her, the two of them sitting half on, half off. He dropped a plate on the table, piled with claws in a bright red sauce. Ialai attacked them immediately. She was one of the few women Dalinar knew who liked masculine food.

“What are we discussing?” Sadeas asked, waving away a master-servant with a chair, then draping his arm around his wife’s shoulders.

“We’re talking about getting Dalinar married,” Ialai said.

“What?” Dalinar demanded, choking on a mouthful of wine.

“That is the point of this, right?” Ialai said. “They want someone who can protect them, someone their family will be too afraid to attack. But Toh and his sister, they’ll want more than just asylum. They’ll want to be part of things. Inject their blood into the royal line, so to speak.”

Dalinar took another long drink.

“You could try water sometime you know, Dalinar,” Sadeas said. “I had some rainwater earlier. Everyone stared at me funny.”

Navani smiled at him. There wasn’t enough wine in the world to prepare him for the gaze behind the smile, so piercing, so appraising.

“This could be what we need,” Gavilar said. “It gives us not only the Shard, but the appearance of speaking for Alethkar. If people outside the kingdom start coming to me for refuge and treaties, we might be able to sway the remaining highprinces. We might be able to unite this country not through further war, but through sheer weight of legitimacy.”

A servant, at long last, arrived with a knife for Dalinar. He took it eagerly, then frowned as the woman walked away.

“What?” Navani asked.

“This little thing?” Dalinar asked, pinching the dainty knife between two fingers and dangling it. “How am I supposed to eat a pork steak with this?”

“Attack it,” Ialai said, making a stabbing motion. “Pretend it’s some thick-necked man who has been insulting your biceps.”

“If someone insulted my biceps, I wouldn’t attack him,” Dalinar said. “I’d refer him to a physician, because obviously something is wrong with his eyes.”

Navani laughed, a musical sound.

“Oh, Dalinar,” Sadeas said. “I don’t think there’s another person on Roshar who could have said that with a straight face.”

Dalinar grunted, then tried to maneuver the little knife into cutting the steak. The meat was growing cold, but still smelled delicious. A single hungerspren started flitting about his head, like a tiny brown fly of the type you saw out in the west near the Purelake.

“What defeated Sunmaker?” Gavilar suddenly asked.

“Hmm?” Ialai said.

“Sunmaker,” Gavilar said, looking from Navani, to Sadeas, to Dalinar. “He united Alethkar. Why did he fail to create a lasting empire?”

“His kids were too greedy,” Dalinar said, sawing at his steak. “Or too weak maybe. There wasn’t one of them that the others would agree to support.”

“No, that’s not it,” Navani said. “They might have united, if the Sunmaker himself could have been bothered to settle on an heir. It’s his fault.”

“He was off in the west,” Gavilar said. “Leading his army to ‘further glory.’ Alethkar and Herdaz weren’t enough for him. He wanted the whole world.”

“So it was his ambition,” Sadeas said.

“No, his greed,” Gavilar said quietly. “What’s the point of conquering if you can never sit back and enjoy it? Shubreth-son-Mashalan, Sunmaker, even the Hierocracy… they all stretched farther and farther until they collapsed. In all the history of mankind, has any conqueror decided they had enough? Has any man just said, ‘This is good. This is what I wanted,’ and gone home?”

“Right now,” Dalinar said, “what I want is to eat my storming steak.” He held up the little knife, which was bent in the middle.

Navani blinked. “How in the Almighty’s tenth name did you do that?”

“Dunno.”

Gavilar stared with that distant, far-off look in his green eyes. A look that was becoming more and more common. “Why are we at war, Brother?”

“This again?” Dalinar said. “Look, it’s not so complicated. Can’t you remember how it was back when we started?”

“Remind me.”

“Well,” Dalinar said, wagging his bent knife. “We looked at this place here, this kingdom, and we realized, ‘Hey, all these people have stuff .’ And we figured… hey, maybe we should have that stuff. So we took it.”

“Oh Dalinar,” Sadeas said, chuckling. “You are a gem.”

“Don’t you ever think about what it meant though?” Gavilar asked. “A kingdom? Something grander than yourself ?”

“That’s foolishness, Gavilar. When people fight, it’s about the stuff That’s it.”

“Maybe,” Gavilar said. “Maybe. There’s something I want you to listen to. The Codes of War, from the old days. Back when Alethkar meant something.”

Dalinar nodded absently as the serving staff entered with teas and fruit to close the meal; one tried to take his steak, and he growled at her. As she backed away, Dalinar caught sight of something. A woman peeking into the room from the other feast hall. She wore a delicate, filmy dress of pale yellow, matched by her blonde hair.

He leaned forward, curious. Toh’s sister Evi was eighteen, maybe nineteen. She was tall, almost as tall as an Alethi, and small of chest. In fact, there was a certain sense of flimsiness to her, as if she were somehow less real than an Alethi. The same went for her brother, with his slender build.

But that hair. It made her stand out, like a candle’s glow in a dark room.

She scampered across the feast hall to her brother, who handed her a drink. She tried to take it with her left hand, which was tied inside a small pouch of yellow cloth. The dress didn’t have sleeves, strangely.

“She kept trying to eat with her safehand,” Navani said, eyebrow cocked.

Ialai leaned down the table toward Dalinar, speaking conspiratorially. “They go about half-clothed out in the far west, you know. Rirans, Iriali, the Reshi. They aren’t as inhibited as these prim Alethi women. I bet she’s quite exotic in the bedroom.…”

Dalinar grunted. Then finally spotted a knife.

In the hand hidden behind the back of a server clearing Gavilar’s plates.

Dalinar kicked at his brother’s chair, breaking a leg off and sending Gavilar toppling to the ground. The assassin swung at the same moment, clipping Gavilar’s ear, but otherwise missing. The wild swing struck the table, driving the knife into the wood.

Dalinar leaped to his feet, reaching over Gavilar and grabbing the assassin by the neck. He spun the would-be killer around and slammed him to the floor with a satisfying crunch. Still in motion, Dalinar grabbed the knife from the table and pounded it into the assassin’s chest.

Puffing, Dalinar stepped back and wiped the rainwater from his eyes. Gavilar sprang to his feet, Shardblade appearing in his hand. He looked down at the assassin, then at Dalinar.

Dalinar kicked at the assassin to be sure he was dead. He nodded to himself, righted his chair, sat down, then leaned over and yanked the man’s knife from his chest. A fine blade.

He washed it off in his wine, then cut off a piece of his steak and shoved it into his mouth. Finally.

“Good pork,” Dalinar noted around the bite.

Across the room, Toh and his sister were staring at Dalinar with looks that mixed awe and terror. He caught a few shockspren around them, like triangles of yellow light, breaking and re-forming. Rare spren, those were.

“Thank you,” Gavilar said, touching his ear and the blood that was dripping from it.

Dalinar shrugged. “Sorry about killing him. You probably wanted to question him, eh?”

“It’s no stretch to guess who sent him,” Gavilar said, settling down, waving away the guards who—belatedly—rushed to help. Navani clutched his arm, obviously shaken by the attack.

Sadeas cursed under his breath. “Our enemies grow desperate. Cowardly. An assassin during a storm? An Alethi should be ashamed of such action.”

Again, everyone in the feast was gawking at the high table. Dalinar cut his steak again, shoving another piece into his mouth. What? He wasn’t going to drink the wine he’d washed the blood into. He wasn’t a barbarian.

“I know I said I wanted you free to make your own choice in regard to a bride,” Gavilar said. “But…”

“I’ll do it,” Dalinar said, eyes forward. Navani was lost to him. He needed to just storming accept that.

“They’re timid and careful,” Navani noted, dabbing at Gavilar’s ear with her napkin. “It might take more time to persuade them.”

“Oh, I wouldn’t worry about that,” Gavilar said, looking back at the corpse. “Dalinar is nothing if not persuasive.”

Chapter 20

Cords to Bind

However, with a dangerous spice, you can be warned to taste lightly. I would that your lesson may not be as painful as my own.

—From Oathbringer, preface

Now this,” Kaladin said, “isn’t actually that serious a wound. I know it looks deep, but it’s often better to be cut deep by a sharp knife than to be raggedly gouged by something dull.”

He pressed the skin of Khen’s arm together and applied the bandage to her cut. “Always use clean cloth you’ve boiled—rotspren love dirty cloth. Infection is the real danger here; you’ll spot it as red along the outsides of the wound that grows and streaks. There will be pus too. Always wash out a cut before binding it.”

He patted Khen’s arm and took back his knife, which had caused the offending laceration when Khen had been using it to cut branches off a fallen tree for firewood. Around her, the other parshmen gathered the cakes they’d dried in the sun.

They had a surprising number of resources, all things considered. Several parshmen had thought to grab metal buckets during their raid— which had worked as pots for boiling—and the waterskins were going to be a lifesaver. He joined Sah, the parshman who had originally been his captor, among the trees of their improvised camp. The parshman was lashing a stone axehead to a branch.

Kaladin took it from him and tested it against a log, judging how well it split the wood. “You need to lash it tighter,” Kaladin said. “Get the leather strips wet and really pull as you wrap it. If you aren’t careful, it’ll fall off on you midswing.”

Sah grunted, taking back the hatchet and grumbling to himself as he undid the lashings. He eyed Kaladin. “You can go check on someone else, human.”

“We should march tonight,” Kaladin said. “We’ve been in one spot too long. And break into small groups, like I said.”

“We’ll see.”

“Look, if there’s something wrong with my advice…”

“Nothing is wrong.”

“But—”

Sah sighed, looking up and meeting Kaladin’s eyes. “Where did a slave learn to give orders and strut about like a lighteyes?”

“My entire life was not spent as a slave.”

“I hate,” Sah continued, “feeling like a child.” He started rewrapping the axehead, tighter this time. “I hate being taught things that I should already know. Most of all, I hate needing your help. We ran. We escaped. Now what? You leap in, start telling us what to do? We’re back to following Alethi orders again.”

Kaladin stayed silent.

“That yellow spren isn’t any better,” Sah muttered. “Hurry up. Keep moving. She tells us we’re free, then with the very next breath berates us for not obeying quickly enough.”

They were surprised that Kaladin couldn’t see the spren. They’d also mentioned to him the sounds they heard, distant rhythms, almost music.

“ ‘Freedom’ is a strange word, Sah,” Kaladin said softly, settling down. “These last few months, I’ve probably been more ‘free’ than at any time since my childhood. You want to know what I did with it? I stayed in the same place, serving another highlord. I wonder if men who use cords to bind are fools, since tradition, society, and momentum are going to tie us all down anyway.”

“I don’t have traditions,” Sah said. “Or society. But still, my ‘freedom’ is that of a leaf. Dropped from the tree, I just blow on the wind and pretend I’m in charge of my destiny.”

“That was almost poetry, Sah.”

“I have no idea what that is.” He pulled the last lashing tight and held up the new hatchet.

Kaladin took it and buried it into the log next to him. “Better.”

“Aren’t you worried, human? Teaching us to make cakes is one thing. Giving us weapons is quite another.”

“A hatchet is a tool, not a weapon.”

“Perhaps,” Sah said. “But with this same chipping and sharpening method you taught, I will eventually make a spear.”

“You act as if a fight is inevitable.”

Sah laughed. “You don’t think it is?”

“You have a choice.”

“Says the man with the brand on his forehead. If they’re willing to do that to one of their own, what brutality awaits a bunch of thieving parshmen?”

“Sah, it doesn’t have to come to war. You don’t have to fight the humans.”

“Perhaps. But let me ask you this.” He set the axe across his lap. “Considering what they did to me, why wouldn’t I?”

Kaladin couldn’t force out an objection. He remembered his own time as a slave: the frustration, powerlessness, anger. They’d branded him with shash because he was dangerous. Because he’d fought back.

Dare he demand this man do otherwise?

“They’ll want to enslave us again,” Sah continued, taking the hatchet and hacking at the log next to him, starting to strip off the rough bark as Kaladin had instructed, so they could have tinder. “We’re money lost, and a dangerous precedent. Your kind will expend a fortune figuring out what changed to give us back our minds, and they’ll find a way to reverse it. They’ll strip from me my sanity, and set me to carrying water again.”

“Maybe… maybe we can convince them otherwise. I know good men among the Alethi lighteyes, Sah. If we talk to them, show them how you can talk and think—that you’re like regular people—they’ll listen. They’ll agree to give you your freedom. That’s how they treated your cousins on the Shattered Plains when they first met.”

Sah slammed the hatchet down into the wood, sending a chip fluttering into the air. “And that’s why we should be free now? Because we’re acting like you? We deserved slavery before, when we were different? It’s all right to dominate us when we won’t fight back, but now it’s not, because we can talk?”

“Well, I mean—”

“That’s why I’m angry! Thank you for what you’re showing us, but don’t expect me to be happy that I need you for it. This just reinforces the belief within you, maybe even within myself, that your people should be the ones who decide upon our freedom in the first place.”

Sah stalked off, and once he was gone, Syl appeared from the underbrush and settled on Kaladin’s shoulder, alert—watching for the Voidspren—but not immediately alarmed.

“I think I can sense a highstorm coming,” she whispered.

“What? Really?”

She nodded. “It’s distant still. A day or three.” She cocked her head.

“I suppose I could have done this earlier, but I didn’t need to. Or know I wanted to. You always had the lists.”

Kaladin took a deep breath. How to protect these people from the storm? He’d have to find shelter. He’d…

I’m doing it again.

“I can’t do this, Syl,” Kaladin whispered. “I can’t spend time with these parshmen, see their side.”

“Why?”

“Because Sah is right. This is going to come to war. The Voidspren will drive the parshmen into an army, and rightly so, after what was done to them. Our kind will have to fight back or be destroyed.”

“Then find the middle ground.”

“Middle ground only comes in war after lots of people have died—and only after the important people are worried they might actually lose. Storms, I shouldn’t be here. I’m starting to want to defend these people! Teach them to fight. I don’t dare—the only way I can fight the Voidbringers is to pretend there’s a difference between the ones I have to protect and the ones I have to kill.”

He trudged through the underbrush and started helping tear down one of the crude tarp tents for the night’s march.

Chapter 21

Set Up to Fall

I am no storyteller, to entertain you with whimsical yarns.

—From Oathbringer, preface

A clamorous, insistent knocking woke Shallan. She still didn’t have a bed, so she slept in a heap of red hair and twisted blankets.

She pulled one of these over her head, but the knocking persisted, followed by Adolin’s annoyingly charming voice. “Shallan? Look, this time I’m going to wait to come in until you’re really sure I should.”

She peeked out at the sunlight, which poured through her balcony window like spilled paint. Morning? The sun was in the wrong place.

Wait… Stormfather. She’d spent the night out as Veil, then slept to the afternoon. She groaned, tossing off sweaty blankets, and lay there in just her shift, head pounding. There was an empty jug of Horneater white in the corner.

“Shallan?” Adolin said. “Are you decent?”

“Depends,” she said, voice croaking, “on the context. I’m decent at sleeping.”

She put hands over her eyes, safehand still wrapped in an improvised bandage. What had gotten into her? Tossing around the symbol of the Ghostbloods? Drinking herself silly? Stabbing a man in front of a gang of armed thugs?

Her actions felt like they’d taken place in a dream.

“Shallan,” Adolin said, sounding concerned. “I’m going to peek in. Palona says you’ve been in here all day.”

She yelped, sitting up and grabbing the bedding. When he looked, he found her bundled there, a frizzy-haired head protruding from blankets— which she had pulled tight up to her chin. He looked perfect, of course. Adolin could look perfect after a storm, six hours of fighting, and a bath in cremwater. Annoying man. How did he make his hair so adorable? Messy in just the right way.

“Palona said you weren’t feeling well,” Adolin said, pushing aside the cloth door and leaning in the doorway.

“Blarg.”

“Is it, um, girl stuff ?”

“Girl stuff,” she said flatly.

“You know. When you… uh…”

“I’m aware of the biology, Adolin, thank you. Why is it that every time a woman is feeling a little odd, men are so quick to blame her cycle? As if she’s suddenly unable to control herself because she has some pains. Nobody thinks that for men. ‘Oh, stay away from Venar today. He sparred too much yesterday, so his muscles are sore, and he’s likely to rip your head off.’ ”

“So it’s our fault.”

“Yes. Like everything else. War. Famine. Bad hair.”

“Wait. Bad hair?”

Shallan blew a lock of it out of her eyes. “Loud. Stubborn. Oblivious to our attempts to fix it. The Almighty gave us messy hair to prepare us for living with men.”

Adolin brought in a small pot of warm washwater for her face and hands.

Bless him. And Palona, who had probably sent it with him.

Damnation, her hand ached. And her head. She remembered occasionally burning off the alcohol last night, but hadn’t ever held enough Stormlight to completely fix the hand. And never enough to make her completely sober.

Adolin set the water down, perky as a sunrise, grinning. “So what is wrong?”

She pulled the blanket up over her head and pulled it tight, like the hood of a cloak. “Girl stuff,” she lied.

“See, I don’t think men would blame your cycle nearly as much if you all didn’t do the same. I’ve courted my share of women, and I once kept track. Deeli was once sick for womanly reasons four times in the same month.”

“We’re very mysterious creatures.”

“I’ll say.” He lifted up the jug and gave it a sniff. “Is this Horneater white?” He looked to her, seeming shocked—but perhaps also a little impressed.

“Got a little carried away,” Shallan grumbled. “Doing investigations about your murderer.”

“In a place serving Horneater moonshine?”

“Back alley of the Breakaway. Nasty place. Good booze though.”

“Shallan!” he said. “You went alone? That’s not safe.”

“Adolin, dear,” she said, finally pulling the blanket back down to her shoulders, “I could literally survive being stabbed with a sword through the chest. I think I’ll be fine with some ruffians in the market.”

“Oh. Right. It’s kind of easy to forget.” He frowned. “So… wait. You could survive all kinds of nasty murder, but you still…”

“Get menstrual cramps?” Shallan said. “Yeah. Mother Cultivation can be hateful. I’m an all-powerful, Shardblade-wielding pseudo-immortal, but nature still sends a friendly reminder every now and then to tell me I should be getting around to having children.”

“No mating,” Pattern buzzed softly on the wall.

“But I shouldn’t be blaming yesterday on that,” Shallan added to Adolin. “My time isn’t for another few weeks. Yesterday was more about psychology than it was about biology.”

Adolin set the jug down. “Yeah, well, you might want to watch out for the Horneater wines.”

“It’s not so bad,” Shallan said with a sigh. “I can burn away the intoxication with a little Stormlight. Speaking of which, you don’t have any spheres with you, do you? I seem to have… um… eaten all of mine.”

He chuckled. “I have one. A single sphere. Father lent it to me so I could stop carrying a lantern everywhere in these halls.”

She tried to bat her eyelashes at him. She wasn’t exactly sure how one did that, or why, but it seemed to work. At the very least, he rolled his eyes and handed over a single ruby mark.

She sucked in the Light hungrily. She held her breath so it wouldn’t puff out when she breathed, and… suppressed the Light. She could do that, she’d found. To prevent herself from glowing or drawing attention. She’d done that as a child, hadn’t she?

Her hand slowly reknit, and she let out a relieved sigh as the headache vanished as well.

Adolin was left with a dun sphere. “You know, when my father explained that good relationships required investment, I don’t think this is what he meant.”

“Mmm,” Shallan said, closing her eyes and smiling.

“Also,” Adolin added, “we have the strangest conversations.”

“It feels natural to have them with you, though.”

“I think that’s the oddest part. Well, you’ll want to start being more careful with your Stormlight. Father mentioned he was trying to get you more infused spheres for practice, but there just aren’t any.”

“What about Hatham’s people?” she said. “They left out lots of spheres in the last highstorm.” That had only been…

She did the math, and found herself stunned. It had been weeks since the unexpected highstorm where she’d first worked the Oathgate. She looked at the sphere between Adolin’s fingers.

Those should all have gone dun by now, she thought. Even the ones renewed most recently. How did they have any Stormlight at all?

Suddenly, her actions the night before seemed even more irresponsible. When Dalinar had commanded her to practice with her powers, he probably hadn’t meant practicing how to avoid getting too drunk.

She sighed, and—still keeping the blanket on—reached for the bowl of washing water. She had a lady’s maid named Marri, but she kept sending her away. She didn’t want the woman discovering that she was sneaking out or changing faces. If she kept on like that, Palona would probably assign the woman to other work.

The water didn’t seem to have any scents or soaps applied to it, so Shallan raised the small basin and then took a long, slurping drink.

“I washed my feet in that,” Adolin noted.

“No you didn’t.” Shallan smacked her lips. “Anyway, thanks for dragging me out of bed.”

“Well,” he said, “I have selfish reasons. I’m kind of hoping for some moral support.”

“Don’t hit the message too hard. If you want someone to believe what you’re telling them, come to your point gradually, so they’re with you the entire time.”

He cocked his head.

“Oh, not that kind of moral,” Shallan said.

“Talking to you can be weird sometimes.”

“Sorry, sorry. I’ll be good.” She sat as primly and attentively as she could, wrapped in a blanket with her hair sticking out like the snarls of a thorn-bush.

Adolin took a deep breath. “My father finally persuaded Ialai Sadeas to speak with me. Father hopes she’ll have some clues about her husband’s death.”

“You sound less optimistic.”

“I don’t like her, Shallan. She’s strange.”

Shallan opened her mouth, but he cut her off.

“Not strange like you,” he said. “Strange… bad strange. She’s always weighing everything and everyone she meets. She’s never treated me as anything other than a child. Will you go with me?”

“Sure. How much time do I have?”

“How much do you need?”

Shallan looked down at herself, huddled in her blankets, frizzy hair tickling her chin. “A lot.”

“Then we’ll be late,” Adolin said, standing up. “It’s not like her opinion of me could get any worse. Meet me at Sebarial’s sitting room. Father wants me to take some reports from him on commerce.”

“Tell him the booze in the market is good.”

“Sure.” Adolin glanced again at the empty jug of Horneater white, then shook his head and left.

An hour later, Shallan presented herself—bathed, makeup done, hair somewhat under control—to Sebarial’s sitting room. The chamber was larger than her room, but notably, the doorway out onto the balcony was enormous, taking up half the wall.

Everyone was out on the wide balcony, which overlooked the field below. Adolin stood by the railing, lost to some contemplation. Behind him, Sebarial and Palona lay on cots, their backs exposed to the sun, getting massages.

A flight of Horneater servants massaged, tended coal braziers, or stood dutifully with warmed wine and other conveniences. The air, particularly in the sun, wasn’t as chilly as it had been most other days. It was almost pleasant.

Shallan found herself caught between embarrassment—this plump, bearded man wearing only a towel was the highprince—and outrage. She’d just taken a cold bath, pouring ladles of water on her own head while shivering. She’d considered that a luxury, as she hadn’t been required to fetch the water herself.

“How is it,” Shallan said, “that I am still sleeping on the floor, while you have cots right here.”

“Are you highprince?” Sebarial mumbled, not even opening his eyes.

“No. I’m a Knight Radiant, which I should think is higher.”

“I see,” he said, then groaned in pleasure at the masseuse’s touch, “and so you can pay to have a cot carried in from the warcamps? Or do you still rely on the stipend I give you? A stipend, I’ll add, that was supposed to pay for your help as a scribe for my accounts—something I haven’t seen in weeks.”

“She did save the world, Turi,” Palona noted from Shallan’s other side. The middle-aged Herdazian woman also hadn’t opened her eyes, and though she lay chest-down, her safehand was tucked only halfway under a towel.

“See, I don’t think she saved it, so much as delayed its destruction. It’s a mess out there, my dear.”

Nearby, the head masseuse—a large Horneater woman with vibrant red hair and pale skin—ordered a round of heated stones for Sebarial. Most of the servants were probably her family. Horneaters did like to be in business together.

“I will note,” Sebarial said, “that this Desolation of yours is going to undermine years of my business planning.”

“You can’t possibly blame me for that,” Shallan said, folding her arms.

“You did chase me out of the warcamps,” Sebarial said, “even though they survived quite well. The remnants of those domes shielded them from the west. The big problem was the parshmen, but those have all cleared out now, marching toward Alethkar. So I plan to go back and reclaim my land there before others seize it.” He opened his eyes and glanced at Shallan. “Your young prince didn’t want to hear that—he worries I will stretch our forces too thin. But those warcamps are going to be vital for trade; we can’t leave them completely to Thanadal and Vamah.”

Great. Another problem to think about. No wonder Adolin looked so distracted. He’d noted they’d be late to visiting Ialai, but didn’t seem particularly eager to be on the move.

“You be a good Radiant,” Sebarial told her, “and get those other Oathgates working. I’ve prepared quite the scheme for taxing passage through them.”

“Callous.”

“Necessary. The only way to survive in these mountains will be to tax the Oathgates, and Dalinar knows it. He put me in charge of commerce. Life doesn’t stop for a war, child. Everyone will still need new shoes, baskets, clothing, wine.”

“And we need massages,” Palona added. “Lots of them, if we’re going to have to live in this frozen wasteland.”

“You two are hopeless,” Shallan snapped, walking across the sunlit balcony to Adolin. “Hey. Ready?”

“Sure.” She and Adolin struck out through the hallways. Each of the eight highprincedoms’ armies in residence at the tower had been granted a quarter of the second or third level, with a few barracks on the first level, leaving most of that level reserved for markets and storage.

Of course, not even the first level had been completely explored. There were so many hallways and bizarre tangents—hidden sets of rooms tucked away behind everything else. Maybe eventually each highprince would rule his quarter in earnest. For now, they occupied little pockets of civilization within the dark frontier that was Urithiru.

Exploration on the upper levels had been completely halted, as they no longer had Stormlight to spare in working the lifts.

They left Sebarial’s quarter, passing soldiers and an intersection with painted arrows on the floor leading to various places, such as the nearest privy. The guards’ checkpoint didn’t look like a barricade, but Adolin had pointed out the boxes of rations, the bags of grain, set in a specific way before the soldiers. Anyone rushing this corridor from the outside would get tangled in all of that, plus face pikemen beyond.

The soldiers nodded to Adolin, but didn’t salute him, though one did bark an order to two men playing cards in a nearby room. The fellows stood up, and Shallan was startled to recognize them. Gaz and Vathah.

“Thought we’d take your guards today,” Adolin said.

My guards. Right. Shallan had a group of soldiers made up of deserters and despicable murderers. She didn’t mind that part, being a despicable murderer herself. But she also had no idea what to do with them.

They saluted her lazily. Vathah, tall and scruffy. Gaz, short with a single brown eye, the other socket covered by a patch. Adolin had obviously already briefed them, and Vathah sauntered out to guard them in the front, while Gaz lingered behind.

Hoping they were far enough away not to hear, Shallan took Adolin by the arm.

“Do we need guards?” she whispered.

“Of course we do.”

“Why? You’re a Shardbearer. I’m a Radiant. I think we’ll be fine.”

“Shallan, being guarded isn’t always about safety. It’s about prestige.”

“I’ve got plenty. Prestige is practically leaking from my nose these days, Adolin.”

“That’s not what I meant.” Adolin leaned down, whispering. “This is for them. You don’t need guards, maybe, but you do need an honor guard. Men to be honored by their position. It’s part of the rules we play by—you get to be someone important, and they get to share in it.”

“By being useless.”

“By being part of what you’re doing,” Adolin said. “Storms, I forget how new you are to all this. What have you been doing with these men?”

“Letting them be, mostly.”

“What of when you need them?”

“I don’t know if I will.”

“You will,” Adolin said. “Shallan, you’re their commander. Maybe not their military commander, as they’re a civil guard, but it amounts to the same thing. Leave them idle, make them assume they’re inconsequential, and you’ll ruin them. Give them something important to do instead, work they’ll be proud of, and they’ll serve you with honor. A failed soldier is often one that has been failed.”

She smiled.

“What?”

“You sound like your father,” she said.

He paused, then looked away. “Nothing wrong with that.”

“I didn’t say there was. I like it.” She held his arm. “I’ll find something to do with my guards, Adolin. Something useful. I promise.”

Gaz and Vathah didn’t seem to think the duty was all that important, from the way they yawned and slouched as they walked, holding out oil lamps, spears at their shoulders. They passed a large group of women carrying water, and then some men carrying lumber to set up a new privy. Most made way for Vathah; seeing a personal guard was a cue to step to the side.

Of course, if Shallan had really wanted to exude importance, she’d have taken a palanquin. She didn’t mind the vehicles; she’d used them extensively in Kharbranth. Maybe it was the part of Veil inside of her, though, that made her resist Adolin whenever he suggested she order one. There was an independence to using her own feet.

They reached the stairwell up, and at the top, Adolin dug in his pocket for a map. The painted arrows weren’t all finished up here. Shallan tugged his arm and pointed the way down a tunnel.

“How can you know that so easily?” he said.

“Don’t you see how wide those strata are?” she asked, pointing to the wall of the corridor. “It’s this way.”

He tucked away his map and gestured for Vathah to lead the way. “Do you really think I’m like my father?” Adolin said softly as they walked. There was a worried sense to his voice.

“You are,” she said, pulling his arm tight. “You’re just like him, Adolin. Moral, just, and capable.”

He frowned.

“What?”

“Nothing.”

“You’re a terrible liar. You’re worried you can’t live up to his expectations, aren’t you?”

“Maybe.”

“Well you have, Adolin. You have lived up to them in every way. I’m certain Dalinar Kholin couldn’t hope for a better son, and… storms. That idea bothers you.”

“What? No!”

Shallan poked Adolin in the shoulder with her freehand. “You’re not telling me something.”

“Maybe.”

“Well, thank the Almighty for that.”

“Not… going to ask what it is?”

“Ash’s eyes, no. I’d rather figure it out. A relationship needs some measure of mystery.”

Adolin fell silent, which was all well and good, because they were approaching the Sadeas section of Urithiru. Though Ialai had threatened to relocate back to the warcamps, she’d made no such move. Likely because there was no denying that this city was now the seat of Alethi politics and power.

They reached the first guard post, and Shallan’s two guards pulled up close to her and Adolin. They exchanged hostile glares with the soldiers in forest-green-and-white uniforms as they were allowed past. Whatever Ialai Sadeas thought, her men had obviously made up their minds.

It was strange how much difference a few steps could make. In here, they passed far fewer workers or merchants, and far more soldiers. Men with dark expressions, unbuttoned coats, and unshaved faces of all varieties. Even the scribes were diff rent—more makeup, but sloppier clothing. It felt like they’d stepped from law into disorder. Loud voices echoed down hallways, laughing raucously. The stripes painted to guide the way were on the walls here rather than the floor, and the paint had been allowed to drip, spoiling the strata. They’d been smeared in places by men who had walked by, their coats brushing the still-wet paint.

The soldiers they passed all sneered at Adolin.

“They feel like gangs,” Shallan said softly, looking over her shoulder at one group.

“Don’t mistake them,” Adolin said. “They march in step, their boots are sturdy, and their weapons well maintained. Sadeas trained good soldiers. It’s just that where Father used discipline, Sadeas used competition. Besides, here, looking too clean will get you mocked. You can’t be mistaken for a Kholin.”

She’d hoped that maybe, now that the truth about the Desolation had been revealed, Dalinar would have an easier time of uniting the highprinces. Well, that obviously wasn’t going to happen while these men blamed Dalinar for Sadeas’s death.

They eventually reached the proper rooms and were ushered in to confront Sadeas’s wife. Ialai was a short woman with thick lips and green eyes. She sat in a throne at the center of the room.

Standing beside her was Mraize, one of the leaders of the Ghostbloods.

Oathbringer: The Stormlight Archive Book 3 copyright © 2017 Dragonsteel Entertainment, LLC