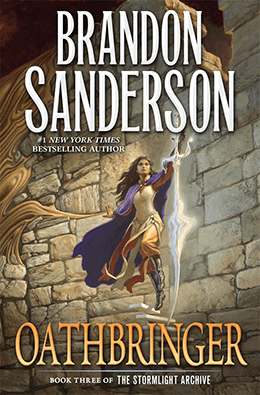

Start reading Oathbringer, the new volume of Brandon Sanderson’s Stormlight Archive epic, right now. For free!

Tor.com is serializing the much-awaited third volume in the Stormlight Archive series every Tuesday until the novel’s November 14, 2017 release date.

Every installment is collected here in the Oathbringer index.

Need a refresher on the Stormlight Archive before beginning Oathbringer? Here’s a summary of what happened in Book 1: The Way of Kings and Book 2: Words of Radiance.

Spoiler warning: Comments will contain spoilers for previous Stormlight books, other works that take place in Sanderson’s cosmere (Elantris, Mistborn, Warbreaker, etc.), and the available chapters of Oathbringer, along with speculation regarding the chapters yet to come.

Chapter 28

Another Option

Finally, I will confess my humanity. I have been named a monster, and do not deny those claims. I am the monster that I fear we all can become.

—From Oathbringer, preface

The decision has been made,’” Teshav read, “ ‘to seal off this Oathgate until we can destroy it. We realize this is not the path you wished for us to take, Dalinar Kholin. Know that the Prime of Azir considers you fondly, and looks forward to the mutual benefit of trade agreements and new treaties between our nations.

“ ‘A magical portal into the very center of our city, however, presents too severe a danger. We will entertain no further pleas to open it, and suggest that you accept our sovereign will. Good day, Dalinar Kholin. May Yaezir bless and guide you.’ ”

Dalinar punched his fist into his palm as he stood in the small stone chamber. Teshav and her ward occupied the writing podium and seat beside it, while Navani had been pacing opposite Dalinar. King Taravangian sat in a chair by the wall, hunched forward with hands clasped, listening with a concerned expression.

That was it then. Azir was out.

Navani touched his arm. “I’m sorry.”

“There’s still Thaylenah,” Dalinar said. “Teshav, see if Queen Fen will speak with me today.”

“Yes, Brightlord.”

He had Jah Keved and Kharbranth from Taravangian, and New Natanan was responding positively. With Thaylenah, Dalinar could at least forge a unified Vorin coalition of all the Eastern states. That model might eventually persuade the nations of the west to join with them.

If anyone remained by then.

Dalinar started pacing again as Teshav contacted Thaylenah. He preferred little rooms like this one; the large chambers were a reminder of how enormous this place was. In a small room like this, you could pretend that you were in a cozy bunker somewhere.

Of course, even in a small chamber there were reminders that Urithiru wasn’t normal. The strata on the walls, like the folds of a fan. Or the holes that commonly showed up at the tops of rooms, right where the walls met the ceiling. The one in this room couldn’t help but remind him of Shallan’s report. Was something in there, watching them? Could a spren really be murdering people in the tower?

It was nearly enough to make him pull out of the place. But where would they go? Abandon the Oathgates? For now, he’d quadrupled patrols and sent Navani’s researchers searching for a possible explanation. At least until he could come up with a solution.

As Teshav wrote to Queen Fen, Dalinar stepped up to the wall, suddenly bothered by that hole. It was right by the ceiling, and too high for him to reach, even if he stood on a chair. Instead he breathed in Stormlight. The bridgemen had described using stones to climb walls, so Dalinar picked up a wooden chair and painted its back with shining light, using the palm of his left hand.

When he pressed the back of the chair against the wall, it stuck. Dalinar grunted, tentatively climbing up onto the seat of the chair, which hung in the air at about table height.

“Dalinar?” Navani asked.

“Might as well make use of the time,” he said, carefully balancing on the chair. He jumped, grabbing the edge of the hole by the ceiling, and pulled himself up to look down it.

It was three feet wide, and about one foot tall. It seemed endless, and he could feel a faint breeze coming out of it. Was that… scraping he heard? A moment later, a mink slunk into the main tunnel from a shadowed crossroad, carrying a dead rat in its mouth. The tubular little animal twitched its snout toward him, then carried its prize away.

“Air is circulating through those,” Navani said as he hopped down off the chair. “The method baffles us. Perhaps some fabrial we have yet to discover?”

Dalinar looked back up at the hole. Miles upon miles of even smaller tunnels threaded through the walls and ceilings of an already daunting system. And hiding in them somewhere, the thing that Shallan had drawn…

“She’s replied, Brightlord!” Teshav said.

“Excellent,” Dalinar said. “Your Majesty, our time is growing short. I’d like—”

“She’s still writing,” Teshav said. “Pardon, Brightlord. She says… um…”

“Just read it, Teshav,” Dalinar said. “I’m used to Fen by now.”

“ ‘Damnation, man. Are you ever going to leave me alone? I haven’t slept a full night in weeks. The Everstorm has hit us twice now; we’re barely keeping this city from falling apart.’ ”

“I understand, Your Majesty,” Dalinar said. “And am eager to send you the aid I promised. Please, let us make a pact. You’ve dodged my requests long enough.”

Nearby, the chair finally dropped from the wall and clattered to the floor. He prepared himself for another round of verbal sparring, of half promises and veiled meanings. Fen had been growing increasingly formal during their exchanges.

The spanreed wrote, then halted almost immediately. Teshav looked at him, grave.

“ ‘No,’ ” she read.

“Your Majesty,” Dalinar said. “This is not a time to forge on alone! Please. I beg you. Listen to me!”

“ ‘You have to know by now,’” came the reply, “ ‘that this coalition is never going to happen. Kholin… I’m baffled, honestly. Your garnet-lit tongue and pleasant words make it seem like you really assume this will work.

“ ‘Surely you see. A queen would have to be either stupid or desperate to let an Alethi army into the very center of her city. I’ve been the former at times, and I might be approaching the latter, but… storms, Kholin. No. I’m not going to be the one who finally lets Thaylenah fall to you people. And on the off chance that you’re sincere, then I’m sorry.’ ”

It had an air of finality to it. Dalinar walked over to Teshav, looking at the inscrutable squiggles on the page that somehow made up the women’s script. “Can you think of anything?” he asked Navani as she sighed and settled down into a chair next to Teshav.

“No. Fen is stubborn, Dalinar.”

Dalinar glanced at Taravangian. Even he had assumed Dalinar’s purpose was conquest. And who wouldn’t, considering his history?

Maybe it would be different if I could speak to them in person, he thought. But without the Oathgates, that was virtually impossible.

“Thank her for her time,” Dalinar said. “And tell her my offer remains on the table.”

Teshav started writing, and Navani looked to him, noting what the scribe hadn’t—the tension in his voice.

“I’m fine,” he lied. “I just need time to think.”

He strode from the room before she could object, and his guards outside fell into step behind him. He wanted some fresh air; an open sky always seemed so inviting. His feet didn’t take him in that direction, however. He instead found himself roaming through the hallways.

What now?

Same as always, people ignored him unless he had a sword in his hand.

Storms, it was like they wanted him to come in swinging.

He stalked the halls for a good hour, getting nowhere. Eventually, Lyn the messenger found him. Panting, she said that Bridge Four needed him, but hadn’t explained why.

Dalinar followed her, Shallan’s sketch a heavy weight in his mind. Had they found another murder victim? Indeed, Lyn led him to the section where Sadeas had been killed.

His sense of foreboding increased. Lyn led him to a balcony, where the bridgemen Leyten and Peet met him. “Who was it?” he asked as he met them.

“Who…” Leyten frowned. “Oh! It’s not that, sir. It’s something else.

This way.”

Leyten led him down some steps onto the wide field outside the first level of the tower, where three more bridgemen waited near some rows of stone planters, probably for growing tubers.

“We noticed this by accident,” Leyten said as they walked among the planters. The hefty bridgeman had a jovial way about him, and talked to Dalinar—a highprince—as easily as he’d talk to friends at a tavern. “We’ve been running patrols on your orders, watching for anything strange. And… well, Peet noticed something strange.” He pointed up at the wall. “See that line?”

Dalinar squinted, picking out a gouge cut into the rock wall. What could score stone like that? It almost looked like…

He looked down at the planter boxes nearest them. And there, hidden between two of them, was a hilt protruding from the stone floor.

A Shardblade.

It was easy to miss, as the blade had sunk all the way down into the rock. Dalinar knelt beside it, then took a handkerchief from his pocket and used it to grab the hilt.

Even though he didn’t touch the Blade directly, he heard a very distant whine, like a scream in the back of someone’s throat. He steeled himself, then yanked the Blade out and set it across the empty planter.

The silvery Blade curved at the end almost like a fishhook. The weapon was even wider than most Shardblades, and near the hilt it rippled in wave-like patterns. He knew this sword, knew it intimately. He’d carried it for decades, since winning it at the Rift all those years ago.

Oathbringer.

He glanced upward. “The killer must have dropped it out that window. It clipped the stone on its way down, then landed here.”

“That’s what we figured, Brightlord,” Peet said.

Dalinar looked down at the sword. His sword.

No. Not mine at all.

He seized the sword, bracing himself for the screams. The cries of a dead spren. They weren’t the shrill, painful shrieks he’d heard when touching other Blades, but more of a whimper. The sound of a man backed into a corner, thoroughly beaten and facing something terrible, but too tired to keep screaming.

Dalinar steeled himself and carried the Blade—a familiar weight—with the flat side against his shoulder. He walked toward a different entrance back into the tower city, followed by his guards, the scout, and the five bridgemen.

You promised to carry no dead Blade, the Stormfather thundered in his head.

“Calm yourself,” Dalinar whispered. “I’m not going to bond it.”

The Stormfather rumbled, low and dangerous.

“This one doesn’t scream as loudly as others. Why?”

It remembers your oath, the Stormfather sent. It remembers the day you won it, and better the day you gave it up. It hates you—but less than it hates others.

Dalinar passed a group of Hatham’s farmers who had been trying, without success, to get some lavis polyps started. He drew more than a few looks; even at a tower populated by soldiers, highprinces, and Radiants, someone carrying a Shardblade in the open was an unusual sight.

“Could it be rescued?” Dalinar whispered as they entered the tower and climbed a stairway. “Could we save the spren who made this Blade?”

I know of no way, the Stormfather said. It is dead, as is the man who broke his oath to kill it.

Back to the Lost Radiants and the Recreance—that fateful day when the knights had broken their oaths, abandoned their Shards, and walked away. Dalinar had witnessed that in a vision, though he still had no idea what had caused it.

Why? What had made them do something so drastic?

He eventually arrived at the Sadeas section of the tower, and though guards in forest green and white controlled access, they couldn’t deny a highprince—particularly not Dalinar. Runners dashed before him to carry word. Dalinar followed them, using their path to judge if he was going in the right direction. He was; she was apparently in her rooms. He stopped at the nice wooden door, and gave Ialai the courtesy of knocking.

One of the runners he had chased here opened the door, still panting. Brightness Sadeas sat in a throne set in the center of the room. Amaram stood at her shoulder.

“Dalinar,” Ialai said, nodding her head to him like a queen greeting a subject.

Dalinar heaved the Shardblade off his shoulder and set it carefully on the floor. Not as dramatic as spearing it through the stones, but now that he could hear the weapon’s screams, he felt like treating it with reverence.

He turned to go.

“Brightlord?” Ialai said, standing up. “What is this in exchange for?”

“No exchange,” Dalinar said, turning back. “That is rightfully yours. My guards found it today; the killer threw it out a window.”

She narrowed her eyes at him.

“I didn’t kill him, Ialai,” Dalinar said wearily.

“I realize that. You don’t have the bite left in you to do something like that.”

He ignored the gibe, looking to Amaram. The tall, distinguished man met his gaze.

“I will see you in judgment someday, Amaram,” Dalinar said. “Once this is done.”

“As I said you could.”

“I wish that I could trust your word.”

“I stand by what I was forced to do, Brightlord,” Amaram said, stepping forward. “The arrival of the Voidbringers only proves I was in the right. We need practiced Shardbearers. The stories of darkeyes gaining Blades are charming, but do you really think we have time for nursery tales now, instead of practical reality?”

“You murdered defenseless men,” Dalinar said through gritted teeth. “Men who had saved your life.”

Amaram stooped, lifting Oathbringer. “And what of the hundreds, even thousands, your wars killed?”

They locked gazes.

“I respect you greatly, Brightlord,” Amaram said. “Your life has been one of grand accomplishment, and you have spent it seeking the good of Alethkar. But you—and take this with the respect I intend—are a hypocrite.

“You stand where you do because of a brutal determination to do what had to be done. It is because of that trail of corpses that you have the luxury to uphold some lofty, nebulous code. Well, it might make you feel better about your past, but morality is not a thing you can simply doff to put on the helm of battle, then put back on when you’re done with the slaughter.”

He nodded his head in esteem, as if he hadn’t just rammed a sword through Dalinar’s gut.

Dalinar spun and left Amaram holding Oathbringer. Dalinar’s stride down the corridors was so quick that his entourage had to scramble to keep up.

He finally found his rooms. “Leave me,” he said to his guards and the bridgemen.

They hesitated, storm them. He turned, ready to lash out, but calmed himself. “I don’t intend to stray in the tower alone. I will obey my own laws. Go.”

They reluctantly retreated, leaving his door unguarded. He passed into his outer common room, where he’d ordered most of the furniture to be placed. Navani’s heating fabrial glowed in a corner, near a small rug and several chairs. They finally had enough Stormlight to power it.

Drawn by the warmth, Dalinar walked up to the fabrial. He was surprised to find Taravangian sitting in one of the chairs, staring into the depths of the shining ruby that radiated heat into the room. Well, Dalinar had invited the king to use this common room when he wished.

Dalinar wanted nothing but to be alone, and he toyed with leaving. He wasn’t sure that Taravangian had noticed him. But that warmth was so welcoming. There were few fires in the tower, and even with the walls to block wind, you always felt chilled.

He settled into the other chair and let out a deep sigh. Taravangian didn’t address him, bless the man. Together they sat by that not-fire, staring into the depths of the gem.

Storms, how he had failed today. There would be no coalition. He couldn’t even keep the Alethi highprinces in line.

“Not quite like sitting by a hearth, is it?” Taravangian finally said, his voice soft.

“No,” Dalinar agreed. “I miss the popping of the logs, the dancing of flamespren.”

“It does have its own charm though. Subtle. You can see the Stormlight moving inside.”

“Our own little storm,” Dalinar said. “Captured, contained, and channeled.”

Taravangian smiled, eyes lit by the ruby’s Stormlight. “Dalinar Kholin… do you mind me asking you something? How do you know what is right?”

“A lofty question, Your Majesty.”

“Please, just Taravangian.”

Dalinar nodded.

“You have denied the Almighty,” Taravangian said.

“I—”

“No, no. I am not decrying you as a heretic. I do not care, Dalinar. I’ve questioned the existence of deity myself.”

“I feel there must be a God,” Dalinar said softly. “My mind and soul rebel at the alternative.”

“Is it not our duty, as kings, to ask questions that make the minds and souls of other men cringe?”

“Perhaps,” Dalinar said. He studied Taravangian. The king seemed so contemplative.

Yes, there still is some of the old Taravangian in there, Dalinar thought. We have misjudged him. He might be slow, but that doesn’t mean he doesn’t think.

“I have felt warmth,” Dalinar said, “coming from a place beyond. A light I can almost see. If there is a God, it was not the Almighty, the one who called himself Honor. He was a creature. Powerful, but still merely a creature.”

“Then how do you know what is right? What guides you?”

Dalinar leaned forward. He thought he could see something larger within the ruby’s light. Something that moved like a fish in a bowl.

Warmth continued to bathe him. Light.

“ ‘On my sixtieth day,’” Dalinar whispered, “ ‘I passed a town whose name shall remain unspoken. Though still in lands that named me king, I was far enough from my home to go unrecognized. Not even those men who handled my face daily—in the form of my seal imprinted upon their letters of authority—would have known this humble traveler as their king.’ ”

Taravangian looked to him, confused.

“It’s a quote from a book,” Dalinar said. “A king long ago took a journey. His destination was this very city. Urithiru.”

“Ah…” Taravangian said. “The Way of Kings, is it? Adrotagia has mentioned that book.”

“Yes,” Dalinar said. “ ‘In this town, I found men bedeviled. There had been a murder. A hogman, tasked in protecting the landlord’s beasts, had been assaulted. He lived long enough, only, to whisper that three of the other hogmen had gathered together and done the crime.

“ ‘I arrived as questions were being raised, and men interrogated. You see, there were four other hogmen in the landlord’s employ. Three of them had been responsible for the assault, and likely would have escaped suspicion had they finished their grim job. Each of the four loudly proclaimed that he was the one who had not been part of the cabal. No amount of interrogation determined the truth.’ ”

Dalinar fell silent.

“What happened?” Taravangian asked.

“He doesn’t say at first,” Dalinar replied. “Throughout his book, he raises the question again and again. Three of those men were violent threats, guilty of premeditated murder. One was innocent. What do you do?”

“Hang all four,” Taravangian whispered.

Dalinar—surprised to hear such bloodthirst from the other man— turned. Taravangian looked sorrowful, not bloodthirsty at all.

“The landlord’s job,” Taravangian said, “is to prevent further murders. I doubt that what the book records actually happened. It is too neat, too simple a parable. Our lives are far messier. But assuming the story did occur as claimed, and there was absolutely no way of determining who was guilty… you have to hang all four. Don’t you?”

“What of the innocent man?”

“One innocent dead, but three murderers stopped. Is it not the best good that can be done, and the best way to protect your people?” Taravangian rubbed his forehead. “Stormfather. I sound like a madman, don’t I? But is it not a particular madness to be charged with such decisions? It’s difficult to address such questions without revealing our own hypocrisy.”

Hypocrite, Amaram accused Dalinar in his mind.

He and Gavilar hadn’t used pretty justifications when they’d gone to war. They’d done as men did: they’d conquered. Only later had Gavilar started to seek validation for their actions.

“Why not let them all go?” Dalinar said. “If you can’t prove who is guilty—if you can’t be sure—I think you should let them go.”

“Yes… one innocent in four is too many for you. That makes sense too.”

“No, any innocent is too many.”

“You say that,” Taravangian said. “Many people do, but our laws will claim innocent men—for all judges are flawed, as is our knowledge. Eventually, you will execute someone who does not deserve it. This is the burden society must carry in exchange for order.”

“I hate that,” Dalinar said softly.

“Yes… I do too. But it’s not a matter of morality, is it? It’s a matter of thresholds. How many guilty may be punished before you’d accept one innocent casualty? A thousand? Ten thousand? A hundred? When you consider, all calculations are meaningless except one. Has more good been done than evil? If so, then the law has done its job. And so… I must hang all four men.” He paused. “And I would weep, every night, for having done it.”

Damnation. Again, Dalinar reassessed his impression of Taravangian. The king was soft-spoken, but not slow. He was simply a man who liked to consider a great long time before committing.

“Nohadon eventually wrote,” Dalinar said, “that the landlord took a modest approach. He imprisoned all four. Though the punishment should have been death, he mixed together the guilt and innocence, and determined that the average guilt of the four should deserve only prison.”

“He was unwilling to commit,” Taravangian said. “He wasn’t seeking justice, but to assuage his own conscience.”

“What he did was, nevertheless, another option.”

“Does your king ever say what he would have done?” Taravangian asked. “The one who wrote the book?”

“He said the only course was to let the Almighty guide, and let each instance be judged differently, depending on circumstances.”

“So he too was unwilling to commit,” Taravangian said. “I would have expected more.”

“His book was about his journey,” Dalinar said. “And his questions. I think this was one he never fully answered for himself. I wish he had.”

They sat by the not-fire for a time before Taravangian eventually stood and rested his hand on Dalinar’s shoulder. “I understand,” he said softly, then left.

He was a good man, the Stormfather said.

“Nohadon?” Dalinar said.

Yes.

Feeling stiff, Dalinar rose from his seat and made his way through his rooms. He didn’t stop at the bedroom, though the hour was growing late, and instead made his way onto his balcony. To look out over the clouds.

Taravangian is wrong, the Stormfather said. You are not a hypocrite, Son of Honor.

“I am,” Dalinar said softly. “But sometimes a hypocrite is nothing more than a person who is in the process of changing.”

The Stormfather rumbled. He didn’t like the idea of change.

Do I go to war with the other kingdoms, Dalinar thought, and maybe save the world? Or do I sit here and pretend that I can do all this on my own?

“Do you have any more visions of Nohadon?” Dalinar asked the Stormfather, hopeful.

I have shown you all that was created for you to see, the Stormfather said. I can show no more.

“Then I should like to rewatch the vision where I met Nohadon,” Dalinar said. “Though let me go fetch Navani before you begin. I want her to record what I say.”

Would you rather I show the vision to her as well? the Stormfather asked. She could record it herself that way.

Dalinar froze. “You can show the visions to others?”

I was given this leave: to choose those who would best be served by the visions. He paused, then grudgingly continued. To choose a Bondsmith.

No, he did not like the idea of being bonded, but it was part of what he’d been commanded to do.

Dalinar barely considered that thought.

The Stormfather could show the visions to others.

“Anyone?” Dalinar said. “You can show them to anyone?”

During a storm, I can approach anyone I choose, the Stormfather said. But you do not have to be in a storm, so you can join a vision in which I have placed someone else, even if you are distant.

Storms! Dalinar bellowed a laugh.

What have I done? the Stormfather asked.

“You’ve just solved my problem!”

The problem from The Way of Kings?

“No, the greater one. I’ve been wishing for a way to meet with the other monarchs in person.” Dalinar grinned. “I think that in a coming highstorm, Queen Fen of Thaylenah is going to have a quite remarkable experience.”

Chapter 29

No Backing Down

So sit back. Read, or listen, to someone who has passed between realms.

—From Oathbringer, preface

Veil prowled through the Breakaway market, hat pulled low, hands in her pockets. Nobody else seemed to be able to hear the beast that she did.

Regular shipments of supplies through Jah Keved via King Taravangian had set the market bustling. Fortunately, with a third Radiant capable of working the Oathgate now, less of Shallan’s time was required.

Spheres that glowed again, and several highstorms as proof that that would persist, had encouraged everyone. Excitement was high, trading brisk. Drink flowed freely from casks emblazoned with the royal seal of Jah Keved. Lurking within it all, somewhere, was a predator that only Veil could hear.

She heard the thing in the silence between laughter. It was the sound of a tunnel extending into the darkness. The feel of breath on the back of your neck in a dark room.

How could they laugh while that void watched?

It had been a frustrating four days. Dalinar had increased patrols to almost ridiculous levels, but those soldiers weren’t watching the right way. They were too easily seen, too disruptive. Veil had set her men to a more targeted surveillance in the market.

So far, they’d found nothing. Her team was tired, as was Shallan, who suff red from the long nights as Veil. Fortunately, Shallan wasn’t doing anything particularly useful these days. Sword training with Adolin each day—more frolicking and flirting than useful swordplay—and the occasional meeting with Dalinar where she had nothing to add but a pretty map.

Veil though… Veil hunted the hunter. Dalinar acted like a soldier: increased patrols, strict rules. He asked his scribes to find him evidence of spren attacking people in historical records.

He needed more than vague explanations and abstract ideas—but those were the very soul of art. If you could explain something perfectly, then you’d never need art. That was the difference between a table and a beautiful woodcutting. You could explain the table: its purpose, its shape, its nature. The woodcutting you simply had to experience.

She ducked into a tent tavern. Did it seem busier in here than on previous nights? Yes. Dalinar’s patrols had people on edge. They were avoiding the darker, more sinister taverns in favor of ones with good crowds and bright lights.

Gaz and Red stood beside a pile of crates, nursing drinks and wearing plain trousers and shirts, not uniforms. She hoped they weren’t too intoxicated yet. Veil pushed up to their position, crossing her arms on the boxes.

“Nothing yet,” Gaz said with a grunt. “Same as the other nights.”

“Not that we’re complaining,” Red added, grinning as he took a long pull on his drink. “This is the kind of soldiering I can really get behind.”

“It’s going to happen tonight,” Veil said. “I can smell it in the air.”

“You said that last night, Veil,” Gaz said.

Three nights ago, a friendly game of cards had turned to violence, and one player had hit another over the head with a bottle. That often wouldn’t have been lethal, but it had hit just right and killed the poor fellow. The perpetrator—one of Ruthar’s soldiers—had been hanged the next day in the market’s central square.

As unfortunate as the event had been, it was exactly what she’d been waiting for. A seed. An act of violence, one man striking the other. She’d mobilized her team and set them in the taverns near where the fight occurred. Watch, she’d said. Someone will get attacked with a bottle, in exactly the same way. Pick someone who looks like the man who died, and watch.

Shallan had done sketches of the murdered man, a short fellow with long drooping mustaches. Veil had distributed them; the men took her as no more than another employee.

Now… they waited.

“The attack will come,” Veil said. “Who are your targets?”

Red pointed out two men in the tent who had mustaches and were of a similar height to the dead man. Veil nodded and dropped a few low-value spheres onto the table. “Get something in you other than booze.”

“Sure, sure,” Red said as Gaz grabbed the spheres. “But tell me, sweetness, don’t you want to stay here with us a little longer?”

“Most men who have made a pass at me end up missing a finger or two, Red.”

“I’d still have plenty left to satisfy you, I promise.”

She looked back at him, then started snickering. “That was a decently good line.”

“Thanks!” He raised his mug. “So…”

“Sorry, not interested.”

He sighed, but raised his mug farther before taking a pull on it. “Where did you come from, anyway?” Gaz said, inspecting her with his single eye.

“Shallan kind of sucked me up along the way, like a boat pulling flotsam into its wake.”

“She does that,” Red said. “You think you’re done. Living out the last light of your sphere, you know? And then suddenly, you’re an honor guard to a storming Knight Radiant, and everyone’s looking up to you.”

Gaz grunted. “Ain’t that true. Ain’t that true.…”

“Keep watch,” Veil said. “You know what to do if something happens.”

They nodded. They’d send one man to the meeting place, while the other tried to tail the attacker. They knew there might be something weird about the man they chased, but she hadn’t told them everything.

Veil walked back to the meeting point, near a dais at the center of the market, close to the well. The dais looked like it had once held some kind of official building, but all that remained was the six-foot-high foundation with steps leading up to it on four sides. Here, Aladar’s officers had set up central policing operations and disciplinary facilities.

She watched the crowds while idly spinning her knife in her fingers. Veil liked watching people. That she shared with Shallan. It was good to know how the two of them were different, but it was also good to know what they had in common.

Veil wasn’t a true loner. She needed people. Yes, she scammed them on occasion, but she wasn’t a thief. She was a lover of experience. She was at her best in a crowded market, watching, thinking, enjoying.

Now Radiant… Radiant could take people or leave them. They were a tool, but also a nuisance. How could they so often act against their own best interests? The world would be a better place if they’d all simply do what Radiant said. Barring that, they could at least leave her alone.

Veil flipped her knife up and caught it. Radiant and Veil shared efficiency. They liked seeing things done well, in the right way. They didn’t suffer fools, though Veil could laugh at them, while Radiant simply ignored them.

Screams sounded in the market.

Finally, Veil thought, catching her knife and spinning. She came alert, eager, drawing in Stormlight. Where?

Vathah came barreling through the crowd, shoving aside a marketgoer. Veil ran to meet him.

“Details!” Veil snapped.

“It wasn’t like you said,” he said. “Follow me.”

The two took off back the way he’d come.

“It wasn’t a bottle to the head.” Vathah said. “My tent is near one of the buildings. The stone ones that were here in the market, you know?”

“And?” she demanded.

Vathah pointed as they drew close. You couldn’t miss the tall structure beside the tent he and Glurv had been watching. At the top, a corpse dangled from an outcropping, hanged by the neck.

Hanged. Storm it. The thing didn’t imitate the attack with the bottle… it imitated the execution that followed!

Vathah pointed. “Killer dropped the person up there, leaving them to twitch. Then the killer jumped down. All that distance, Veil. How—”

“Where?” she demanded.

“Glurv is tailing,” Vathah said, pointing.

The two charged in that direction, shoving their way through the crowds. They eventually spotted Glurv up ahead, standing on the edge of the well, waving. He was a squat man with a face that always looked swollen, as if it were trying to burst through its skin.

“Man wearing all black,” he said. “Ran straight toward the eastern tunnels!” He pointed toward where troubled marketgoers were peering down a tunnel, as if someone had just passed them in a rush.

Veil dashed in that direction. Vathah stayed with her longer than Glurv— but with Stormlight, she maintained a sprint no ordinary person could match. She burst into the indicated hallway and demanded to know if anyone had seen a man pass this way. A pair of women pointed.

Veil followed, heart beating violently, Stormlight raging within her. If she failed the chase, she’d have to wait for two more people to be assaulted—if it even happened again. The creature might hide, now that it knew she was watching.

She sprinted down this hallway, leaving behind the more populated sections of the tower. A few last people pointed down a tunnel at her shouted question.

She was beginning to lose hope as she reached the end of the hallway at an intersection, and looked one way, then the other. She glowed brightly to light the corridors for a distance, but she saw nothing in either.

She let out a sigh, slumping against the wall.

“Mmmm…” Pattern said from her coat. “It’s there.”

“Where?” Shallan asked.

“To the right. The shadows are off. The wrong pattern.”

She stepped forward, and something split out of the shadows, a figure that was jet black—though like a liquid or a polished stone, it reflected her light. It scrambled away, its shape wrong. Not fully human.

Veil ran, heedless of the danger. This thing might be able to hurt her— but the mystery was the greater threat. She needed to know these secrets.

Shallan skidded around a corner, then barreled down the next tunnel. She managed to follow the broken piece of shadow, but she couldn’t quite catch it.

The chase led her deeper into the far reaches of the tower’s ground floor, to areas barely explored, where the tunnels grew increasingly confusing. The air smelled of old things. Of dust and stone left alone for ages. The strata danced on the walls, the speed of her run making them seem to twist around her like threads in a loom.

The thing dropped to all fours, light from Shallan’s glow reflecting off its coal skin. It ran, frantic, until it hit a turn in the tunnel ahead and squeezed into a hole in the wall, two feet wide, near the floor.

Radiant dropped to her knees, spotting the thing as it wriggled out the other side of the hole. Not that thick, she thought, standing. “Pattern!” she demanded, thrusting her hand to the side.

She attacked the wall with her Shardblade, slicing chunks free, dropping them to the floor with a clatter. The strata ran all the way through the stone, and the pieces she carved off had a forlorn, broken beauty to them.

Engorged with Light, she shoved up against the sliced wall, finally breaking through into a small room beyond.

Much of its floor was taken up by the mouth of a pit. Circled by stone steps with no railing, the hole bored down through the rock into darkness. Radiant lowered her Shardblade, letting it slice into the rock at her feet. A hole. Like her drawing of spiraling blackness, a pit that seemed to descend into the void itself.

She released her Shardblade, falling to her knees.

“Shallan?” Pattern asked, rising up from the ground near where the Blade had vanished.

“We’ll need to descend.”

“Now?”

She nodded. “But first… first, go and get Adolin. Tell him to bring soldiers.”

Pattern hummed. “You won’t go alone, will you?”

“No. I promise. Can you make your way back?”

Pattern buzzed affirmatively, then zipped off across the ground, dimpling the floor of the rock. Curiously, the wall near where she’d broken in showed the rust marks and remnants of ancient hinges. So there was a secret door to get into this place.

Shallan kept her word. She was drawn toward that blackness, but she wasn’t stupid. Well, mostly not stupid. She waited, transfixed by the pit, until she heard voices from the hallway behind her. He can’t see me in Veil’s clothing! she thought, and started to reawaken. How long had she been kneeling there?

She took off Veil’s hat and long white coat, then hid them behind the debris. Stormlight enfolded her, painting the image of a havah over her trousers, gloved hand, and tight buttoned shirt.

Shallan. She was Shallan again—innocent, lively Shallan. Quick with a quip, even when nobody wanted to hear it. Earnest, but sometimes over-eager. She could be that person.

That’s you, a part of her cried as she adopted the persona. That’s the real you. Isn’t it? Why do you have to paint that face over another?

She turned as a short, wiry man in a blue uniform entered the room, grey dusting his temples. What was his name again? She’d spent some time around Bridge Four in the last few weeks, but still hadn’t learned them all.

Adolin strode in next, wearing Kholin blue Shardplate, faceplate up, Blade resting on his shoulder. Judging from the sounds out in the hallway— and the Herdazian faces that peeked into the room—he had brought not only soldiers, but the entirety of Bridge Four.

That included Renarin, who clomped in after his brother, clad in slate-colored Shardplate. Renarin looked far less frail when fully armored, though his face didn’t seem like a soldier’s, even if he had stopped wearing his spectacles.

Pattern approached and tried to slide up her illusory dress, but then stopped, backing away and humming in pleasure at the lie. “I found him!” he proclaimed. “I found Adolin!”

“I see that,” Shallan said.

“He came at me,” Adolin said, “in the training rooms, screaming that you’d found the killer. Said that if I didn’t come, you’d probably—and I quote—‘go do something stupid without letting me watch.’ ”

Pattern hummed. “Stupidity. Very interesting.”

“You should visit the Alethi court sometime,” Adolin said, stepping over to the pit. “So…”

“We tracked the thing that has been assaulting people,” Shallan said. “It killed someone in the market, then it came here.”

“The… thing?” one of the bridgemen asked. “Not a person?”

“It’s a spren,” Shallan whispered. “But not like one I’ve ever seen. It’s able to imitate a person for a time—but it eventually becomes something else. A broken face, a twisted shape…”

“Sounds like that girl you’ve been seeing, Skar,” one of the bridgemen noted.

“Ha ha,” Skar said dryly. “How about we toss you in that pit, Eth, and see how far down this thing goes?”

“So this spren,” Lopen said, approaching the pit, “it, sure, killed Highprince Sadeas?”

Shallan hesitated. No. It had killed Perel in copying the Sadeas murder, but someone else had murdered the highprince. She glanced at Adolin, who must have been thinking the same thing, for how solemn his expression was.

The spren was the greater threat—it had performed multiple murders. Still, it made her uncomfortable to acknowledge that her investigation hadn’t taken them a single step closer to finding who had killed the highprince.

“We must have passed by this point a dozen times,” a soldier said from behind. Shallan started; that voice was female. Indeed, she’d mistaken one of Dalinar’s scouts—the short woman with long hair—for another bridgeman, though her uniform was diff rent. She was inspecting the cuts Shallan had made to get into this room. “Don’t you remember scouting right past that curved hallway outside, Teft?”

Teft nodded, rubbing his bearded chin. “Yeah, you’re right, Lyn. But why hide a room like this?”

“There’s something down there,” Renarin whispered, leaning out over the pit. “Something… ancient. You’ve felt it, haven’t you?” He looked up at Shallan, then the others in the room. “This place is weird; this whole tower is weird. You’ve noticed it too, right?”

“Kid,” Teft said, “you’re the expert on what’s weird. We’ll trust your word.”

Shallan looked with concern toward Renarin at the insult. He just grinned, as one of the other bridgemen slapped him on the back—Plate notwithstanding—while Lopen and Rock started arguing over who was truly the weirdest among them. In a moment of surprise, she realized that Bridge Four had actually assimilated Renarin. He might be the lighteyed son of a highprince, resplendent in Shardplate, but here he was just another bridgeman.

“So,” one of the men said, a handsome, muscled fellow with arms that seemed too long for his body, “I assume we’re heading down into this awful crypt of terror?”

“Yes,” Shallan said. She thought his name was Drehy.

“Storming lovely,” Drehy said. “Marching orders, Teft?”

“That’s up to Brightlord Adolin.”

“I brought the best men I could find,” Adolin said to Shallan. “But I feel like I should bring an entire army instead. You sure you want to do this now?”

“Yes,” Shallan said. “We have to, Adolin. And… I don’t know that an army would make a difference.”

“Very well. Teft, give us a hefty rearguard. I don’t fancy having something sneak up on us. Lyn, I want accurate maps—stop us if we get too far ahead of your drawing. I want to know my exact line of retreat. We go slowly, men. Be ready to perform a controlled, careful retreat if I command it.”

Some shuffling of personnel followed. Then the group finally started down the staircase, single file, Shallan and Adolin near the center of the pack. The steps jutted right from the wall, but were wide enough that people would be able to pass on their way up, so there was no danger of falling off She tried to keep from brushing anyone, as it might disturb the illusion that she was wearing her dress.

The sound of their footsteps vanished into the void. Soon they were alone with the timeless, patient darkness. The light of the sphere lanterns the bridgemen carried didn’t seem to stretch far in that pit. It reminded Shallan of the mausoleum carved into the hill near her manor, where ancient Davar family members had been Soulcast to statues.

Her father’s body hadn’t been placed there. They had lacked the funds to pay for a Soulcaster—and besides, they’d wanted to pretend he was alive. She and her brothers had burned the body, as the darkeyes did.

Pain…

“I have to remind you, Brightness,” Teft said from in front of her, “you can’t expect anything… extraordinary from my men. For a bit, some of us sucked up light and strutted about like we were Stormblessed. That stopped when Kaladin left.”

“It’ll come back, gancho!” Lopen said from behind her. “When Kaladin returns, we’ll glow again good.”

“Hush, Lopen,” Teft said. “Keep your voice down. Anyway, Brightness, the lads will do their best, but you need to know what—and what not—to expect.”

Shallan hadn’t been expecting Radiant powers from them; she’d known about their limitation already. All she needed were soldiers. Eventually, Lopen tossed a diamond chip into the hole, earning him a glare from Adolin.

“It might be down there waiting for us,” the prince hissed. “Don’t give it warning.”

The bridgeman wilted, but nodded. The sphere bounced as a visible pinprick below, and Shallan was glad to know that at least there was an end to this descent. She’d begun to imagine an infinite spiral, like with old Dilid, one of the ten fools. He ran up a hillside toward the Tranquiline Halls with sand sliding beneath his feet—running for eternity, but never making progress.

Several bridgemen let out audible sighs of relief as they finally reached the bottom of the shaft. Here, piles of splinters scattered at the edges of the round chamber, covered in decayspren. There had once been a banister for the steps, but it had fallen to the effects of time.

The bottom of the shaft had only one exit, a large archway more elaborate than others in the tower. Up above, almost everything was the same uniform stone—as if this whole tower had been carved in one go. Here, the archway was of separately placed stones, and the walls of the tunnel beyond were lined with bright mosaic tiles.

Once they entered the hall, Shallan gasped, holding up a diamond broam. Gorgeous, intricate pictures of the Heralds—made of thousands of tiles— adorned the ceiling, each in a circular panel.

The art on the walls was more enigmatic. A solitary figure hovering above the ground before a large blue disc, arms stretched to the side as if to embrace it. Depictions of the Almighty in his traditional form as a cloud bursting with energy and light. A woman in the shape of a tree, hands spreading toward the sky and becoming branches. Who would have thought to find pagan symbols in the home of the Knights Radiant?

Other murals depicted shapes that reminded her of Pattern, windspren… ten kinds of spren. One for each order?

Adolin sent a vanguard a short distance ahead, and soon they returned. “Metal doors ahead, Brightlord,” Lyn said. “One on each side of the hall.”

Shallan pried her eyes away from the murals, joining the main body of the force as they moved. They reached the large steel doors and stopped, though the corridor itself continued onward. At Shallan’s prompting, the bridgemen tried them, but couldn’t get them open.

“Locked,” Drehy said, wiping his brow.

Adolin stepped forward, sword in hand. “I’ve got a key.”

“Adolin…” Shallan said. “These are artifacts from another time. Valuable and precious.”

“I won’t break them too much,” he promised.

“But—”

“Aren’t we chasing a murderer?” he said. “Someone who is likely to, say, hide in a locked room?”

She sighed, then nodded as he waved everyone back. She tucked her safehand, which had brushed him, back under her arm. It was so strange to feel like she was wearing a glove, but to see her hand as sleeved. Would it really have been so bad to let Adolin know about Veil?

A part of her panicked at the idea, so she let go of it quickly.

Adolin rammed his Blade through the door just above where the lock or bar would be, then swept it down. Teft tried the door, and was able to shove it open, hinges grinding loudly.

The bridgemen ducked in first, spears in hand. For all Teft’s insistence that she wasn’t to expect anything exceptional of them, they took point without orders, even though there were two Shardbearers at the ready.

Adolin rushed in after the bridgemen to secure the room, though Renarin wasn’t paying much attention. He’d walked a few steps farther down the main corridor, and now stood still, staring deeper into the depths, sphere held absently in one gauntleted hand, Shardblade in the other.

Shallan stepped up hesitantly beside him. A cool breeze blew from behind them, as if being sucked into that darkness. The mystery lurked in that direction, the captivating depths. She could sense it more distinctly now. Not an evil really, but a wrongness. Like the sight of a wrist hanging from an arm after the bone is broken.

“What is it?” Renarin whispered. “Glys is frightened, and won’t speak.”

“Pattern doesn’t know,” Shallan said. “He calls it ancient. Says it’s of the enemy.”

Renarin nodded.

“Your father doesn’t seem to be able to feel it,” Shallan said. “Why can we?”

“I… I don’t know. Maybe—”

“Shallan?” Adolin said, looking out of the room, his faceplate up. “You should see this.”

The wreckage inside the room was more decayed than most they’d found in the tower. Rusted clasps and screws clung to bits of wood. Decomposed heaps ran in rows, containing bits of fragile covers and spines.

A library. They’d finally found the books Jasnah had dreamed of discovering.

They were ruined.

With a sinking feeling, Shallan moved through the room, nudging at piles of dust and splinters with her toes, frightening off decayspren. She found some shapes of books, but they disintegrated at her touch. She knelt between two rows of fallen books, feeling lost. All that knowledge… dead and gone.

“Sorry,” Adolin said, standing awkwardly nearby.

“Don’t let the men disturb this. Maybe… maybe there’s something Navani’s scholars can do to recover it.”

“Want us to search the other room?” Adolin asked.

She nodded, and he clanked off. A short time later, she heard hinges creak as Adolin forced open the door.

Shallan suddenly felt exhausted. If these books here were gone, then it was unlikely they’d find others better preserved.

Forward. She rose, brushing off her knees, which only reminded her that her dress wasn’t real. You aren’t here for this secret anyway.

She stepped out into the main hallway, the one with the murals. Adolin and the bridgemen were exploring the room on the other side, but a quick glance showed Shallan that it was a mirror of the one they’d left, furnished only with piles of debris.

“Um… guys?” Lyn, the scout, called. “Prince Adolin? Brightness Radiant?”

Shallan turned from the room. Renarin had walked farther down the corridor. The scout had followed him, but had frozen in the hallway. Renarin’s sphere illuminated something in the distance. A large mass that reflected the light, like glistening tar.

“We shouldn’t have come here,” Renarin said. “We can’t fight this. Stormfather.” He stumbled backward. “Stormfather…”

The bridgemen hastened into the hallway in front of Shallan, between her and Renarin. At a barked order from Teft, they made a formation spanning from one side of the main hallway to the other: a line of men holding spears low, with a second line behind holding more spears higher in an overhand grip.

Adolin burst out of the second library room, then gaped at the undulating shape in the distance. A living darkness.

That darkness seeped down the hallway. It wasn’t fast, but there was an inevitability about the way it coated everything, flowing up the sides of the walls, onto the ceiling. On the ground, shapes split from the main mass, becoming figures that stepped as if from the surf. Creatures that had two feet and soon grew faces, with clothing that rippled into existence.

“She’s here,” Renarin whispered. “One of the Unmade. Re-Shephir… the Midnight Mother.”

“Run, Shallan!” Adolin shouted. “Men, start back up the hall.” Then—of course—he charged at the flood of things.

The figures… they look like us, Shallan thought, stepping back, farther from the line of bridgemen. There was one midnight creature that looked like Teft, and another that was a copy of Lopen. Two larger shapes seemed to be wearing Shardplate. Except they were made of shiny tar, their features blobby, imperfect.

The mouths opened, sprouting spiny teeth.

“Make a careful retreat, like the prince ordered!” Teft called. “Don’t get boxed in, men! Hold the line! Renarin!”

Renarin still stood out in front, holding forth his Shardblade: long and thin, with a waving pattern to the metal. Adolin reached his brother, then grabbed his arm and tried to tow him back.

He resisted. He seemed mesmerized by that line of forming monsters.

“Renarin! Attention!” Teft shouted. “To the line!”

The boy’s head snapped up at the command and he scrambled—as if he weren’t the cousin of the king—to obey his sergeant’s order. Adolin retreated with him, and the two fell into formation with the bridgemen. Together, they pulled backward through the main hall.

Shallan backed up, staying roughly twenty feet behind the formation. Suddenly, the enemy moved with a burst of speed. Shallan cried out, and the bridgemen cursed, turning spears as the main mass of darkness swept up along the sides of the corridor, covering the beautiful murals.

The midnight figures dashed forward, charging the line. An explosive, frantic clash followed, bridgemen holding formation and striking at creatures who suddenly began forming on the right and left, coming out of the blackness on the walls. The things bled vapor when struck, a darkness that hissed from them and dissipated into the air.

Like smoke, Shallan thought.

The tar swept down from the walls, surrounding the bridgemen, who circled to keep themselves from being attacked at the rear. Adolin and Renarin fought at the very front, hacking with Blades, leaving dark figures to hiss and gush smoke in pieces.

Shallan found herself separated from the soldiers, an inky blackness between them. There didn’t seem to be a duplicate for her.

The midnight faces bristled with teeth. Though they thrust with spears, they did so awkwardly. They struck true now and then, wounding a bridgeman, who would pull back into the center of the formation to be hastily bandaged by Lyn or Lopen. Renarin fell into the center and started to glow with Stormlight, healing those who were hurt.

Shallan watched all this, feeling a numbing trance settle over her. “I… know you,” she whispered to the blackness, realizing it was true. “I know what you’re doing.”

Men grunted and stabbed. Adolin swept before himself, Shardblade trailing black smoke from the creatures’ wounds. He chopped apart dozens of the things, but new ones continued forming, wearing familiar shapes. Dalinar. Teshav. Highprinces and scouts, soldiers and scribes.

“You try to imitate us,” Shallan said. “But you fail. You’re a spren. You don’t quite understand.”

She stepped toward the surrounded bridgemen.

“Shallan!” Adolin called, grunting as he cleaved three figures before him. “Escape! Run!”

She ignored him, stepping up to the darkness. In front of her—at the closest point of the ring—Drehy stabbed a figure straight through the head, sending it stumbling back. Shallan seized its shoulders, spinning it toward her. It was Navani, a gaping hole in her face, black smoke escaping with a hiss. Even ignoring that, the features were off. The nose too big, one eye a little higher than the other.

It dropped to the floor, writhing as it deflated like a punctured wineskin.

Shallan strode right up to the formation. The things fled her, shying to the sides. Shallan had the distinct and terrifying impression that these things could have swept the bridgemen away at will—overwhelming them in a terrible black tide. But the Midnight Mother wanted to learn; she wanted to fight with spears.

If that was so, however, she was growing impatient. The newer figures forming up were increasingly distorted, more bestial, spiny teeth spilling from their mouths.

“Your imitation is pathetic,” Shallan whispered. “Here. Let me show you how it’s done.”

Shallan drew in her Stormlight, going alight like a beacon. Things screamed, pulling away from her. As she stepped around the formation of worried bridgemen—wading into the blackness at their left flank—figures extended from her, shapes growing from light. The people from her recently rebuilt collection.

Palona. Soldiers from the hallways. A group of Soulcasters she’d passed two days ago. Men and women from the markets. Highprinces and scribes. The man who had tried to pick up Veil at the tavern. The Horneater she’d stabbed in the hand. Soldiers. Cobblers. Scouts. Washwomen. Even a few kings.

A glowing, radiant force.

Her figures spread out to surround the beleaguered bridgemen like sentries. This new, glowing force drove the enemy monsters back, and the tar withdrew along the sides of the hall, until the path of retreat was open. The Midnight Mother dominated the darkness at the end of the hall, the direction they had not yet explored. It waited there, and did not recede farther.

The bridgemen relaxed, Renarin muttering as he healed the last few who had been hurt. Shallan’s cohort of glowing figures moved forward and formed a line with her, between darkness and bridgemen.

The creatures formed again from the blackness ahead, growing more ferocious, like beasts. Featureless blobs with teeth sprouting from slit mouths.

“How are you doing this?” Adolin asked, voice ringing from within his helm. “Why are they afraid?”

“Has someone with a knife—not knowing who you were—ever tried to threaten you?”

“Yeah. I just summoned my Shardblade.”

“It’s a little like that.” Shallan stepped forward, and Adolin joined her. Renarin summoned his Blade and took a few quick steps to reach them, his Plate clicking.

The darkness pulled back, revealing that the hallway opened up into a room ahead. As she approached, Shallan’s Stormlight illuminated a bowl-like chamber. The center was dominated by a heaving black mass that undulated and pulsed, stretching from floor to ceiling some twenty feet above.

The midnight beasts tested forward against her light, no longer seeming as intimidated.

“We have to choose,” Shallan said to Adolin and Renarin. “Retreat or attack?”

“What do you think?”

“I don’t know. This creature… she’s been watching me. She’s changed how I see the tower. I feel like I understand her, a connection I cannot explain. That can’t be a good thing, right? Can we even trust what I think?”

Adolin raised his faceplate and smiled at her. Storms, that smile. “Highmarshal Halad always said that to beat someone, you must first know them. It’s become one of the rules we follow in warfare.”

“And… what did he say about retreat?”

“ ‘Plan every battle as if you will inevitably retreat, but fight every battle like there is no backing down.’”

The main mass in the chamber undulated, faces appearing from its tarry surface—pressing out as if trying to escape. There was something beneath the enormous spren. Yes, it was wrapped around a pillar that reached from the floor of the circular room to its ceiling.

The murals, the intricate art, the fallen troves of information… This place was important.

Shallan clasped her hands before herself, and the Patternblade formed in her palms. She twisted it in a sweaty grip, falling into the dueling stance Adolin had been teaching her.

Holding it immediately brought pain. Not the screaming of a dead spren. Pain inside. The pain of an Ideal sworn, but not yet overcome.

“Bridgemen,” Adolin called. “You willing to give it another go?”

“We’ll last longer than you will, gancho! Even with your fancy armor.”

Adolin grinned and slammed his faceplate down. “At your word, Radiant.”

She sent her illusions in, but the darkness didn’t shy before them as it had previously. Black figures attacked her illusions, testing to find that they weren’t real. Dozens of these midnight men clogged the way forward.

“Clear the way for me to the thing in the center,” she said, trying to sound more certain than she felt. “I need to get close enough to touch her.”

“Renarin, can you guard my back?” Adolin asked.

Renarin nodded.

Adolin took a deep breath, then charged into the room, bursting right through the middle of an illusion of his father. He struck at the first midnight man, chopping it down, then began sweeping around him in a frenzy.

Bridge Four shouted, rushing in behind him. Together, they began to form a path for Shallan, slaying the creatures between her and the pillar.

She walked through the bridgemen, a rank of them forming a spear line to either side of her. Ahead, Adolin pushed toward the pillar, Renarin at his back preventing him from being surrounded, bridgemen in turn pushing up along the sides to keep Renarin from being overwhelmed.

The monsters no longer bore even a semblance of humanity. They struck Adolin, too-real claws and teeth scraping his armor. Others clung to him, trying to weigh him down or find chinks in the Shardplate.

They know how to face men like him, Shallan thought, still holding her Shardblade in one hand. Why then do they fear me?

Shallan wove Light, and a version of Radiant appeared near Renarin. The creatures attacked it, leaving Renarin for a moment—unfortunately, most of her illusions had fallen, collapsing into Stormlight as they were disrupted again and again. She could have kept them going, she thought, with more practice.

Instead, she wove versions of herself. Young and old, confident and frightened. A dozen different Shallans. With a shock, she realized that several were pictures she’d lost, self-portraits she’d practiced with a mirror, as Dandos the Oilsworn had insisted was vital for an aspiring artist.

Some of her selves cowered; others fought. For a moment Shallan lost herself, and she even let Veil appear among them. She was those women, those girls, every one of them. And none of them were her. They were things she used, manipulated. Illusions.

“Shallan!” Adolin shouted, voice straining as Renarin grunted and ripped midnight men off him. “Whatever you’re going to do, do it now!”

She’d stepped up to the front of the column the soldiers had won for her, right near Adolin. She tore her gaze away from a child Shallan dancing among the midnight men. Before her, the main mass—coating the pillar in the center of the room—bubbled with faces that stretched against the surface, mouths opening to scream, then submerged like men drowning in tar.

“Shallan!” Adolin said again.

That pulsing mass, so terrible, but so captivating.

The image of the pit. The twisting lines of the corridors. The tower that couldn’t be completely seen. This was why she’d come.

Shallan strode forward, arm out, and let the illusory sleeve covering her hand vanish. She pulled off her glove, stepped right up to the mass of tar and voiceless screams.

Then pressed her safehand against it.

Chapter 30

Mother of Lies

Listen to the words of a fool.

—From Oathbringer, preface

Shallan was open to this thing. Laid bare, her skin split, her soul gaping wide. It could get in.

It was also open to her.

She felt its confused fascination with humankind. It remembered men— an innate understanding, much as newborn mink kits innately knew to fear the skyeel. This spren was not completely aware, not completely cognizant. She was a creation of instinct and alien curiosity, drawn to violence and pain like scavengers to the scent of blood.

Shallan knew Re-Shephir at the same time as the thing came to know her. The spren tugged and prodded at Shallan’s bond with Pattern, seeking to rip it free and insert herself instead. Pattern clung to Shallan, and she to him, holding on for dear life.

She fears us, Pattern’s voice buzzed in her head. Why does she fear us?

In her mind’s eye, Shallan envisioned herself holding tightly to Pattern in his humanoid form, the two of them huddled down before the spren’s attack. That image was all she could see at the moment, for the room— and everything in it—had dissolved to black.

This thing was ancient. Created long ago as a splinter of the soul of something even more terrible, Re-Shephir had been ordered to sow chaos, spawning horrors to confuse and destroy men. Over time, slowly, she’d become increasingly intrigued by the things she murdered.

Her creations had come to imitate what she saw in the world, but lacking love or affection. Like stones come alive, content to be killed or to kill with no attachment or enjoyment. No emotions beyond an overpowering curiosity, and that ephemeral attraction to violence.

Almighty above… it’s like a creationspren. Only so, so wrong.

Pattern whimpered, huddled against Shallan in his shape of a man with a stiff robe and a moving pattern for a head. She tried to shield him from the onslaught.

Fight every battle… as if there is… no backing down.

Shallan looked into the depths of the swirling void, the dark spinning soul of Re-Shephir, the Midnight Mother. Then, growling, Shallan struck.

She didn’t attack like the prim, excitable girl who had been trained by cautious Vorin society. She attacked like the frenzied child who had murdered her mother. The cornered woman who had stabbed Tyn through the chest. She drew upon the part of her that hated the way everyone assumed she was so nice, so sweet. The part of her that hated being described as diverting or clever.

She drew upon the Stormlight within, and pushed herself farther into Re-Shephir’s essence. She couldn’t tell if it was actually happening—if she was pushing her physical body farther into the creature’s tar—or if this was all a representation of someplace else. A place beyond this room in the tower, beyond even Shadesmar.

The creature trembled, and Shallan finally saw the reason for its fear. It had been trapped. The event had happened recently in the spren’s reckoning, though Shallan had the impression that in fact centuries upon centuries had passed.

Re-Shephir was terrified of it happening again. The imprisonment had been unexpected, presumed impossible. And it had been done by a Lightweaver like Shallan, who had understood this creature.

It feared her like an axehound might fear someone with a voice similar to that of its harsh master.

Shallan hung on, pressing herself against the enemy, but realization washed over her—the understanding that this thing was going to know her completely, discover each and every one of her secrets.

Her ferocity and determination wavered; her commitment began to seep away.

So she lied. She insisted that she wasn’t afraid. She was committed. She’d always been that way. She would continue that way forever.

Power could be an illusion of perception. Even within yourself.

Re-Shephir broke. It screeched, a sound that vibrated through Shallan. A screech that remembered its imprisonment and feared something worse.

Shallan dropped backward in the room where they’d been fighting. Adolin caught her in a steel grip, going down on one knee with an audible crack of Plate against stone. She heard that echoing scream fading. Not dying. Fleeing, escaping, determined to get as far from Shallan as it could.

When she forced her eyes open, she found the room clean of the darkness. The corpses of the midnight creatures had dissolved. Renarin quickly knelt next to a bridgeman who had been hurt, removing his gauntlet and infusing the man with healing Stormlight.

Adolin helped Shallan sit up, and she tucked her exposed safehand under her other arm. Storms… she’d somehow kept up the illusion of the havah.

Even after all of that, she didn’t want Adolin to know of Veil. She couldn’t.

“Where?” she asked him, exhausted. “Where did it go?”

Adolin pointed toward the other side of the room, where a tunnel extended farther down into the depths of the mountain. “It fled in that direction, like moving smoke.”

“So… should we chase it down?” Eth asked, making his way carefully toward the tunnel. His lantern revealed steps cut into the stone. “This goes down a long ways.”

Shallan could feel a change in the air. The tower was… different. “Don’t give chase,” she said, remembering the terror of that conflict. She was more than happy to let the thing run. “We can post guards in this chamber, but I don’t think she’ll return.”

“Yeah,” Teft said, leaning on his spear and wiping sweat from his face. “Guards seem like a very, very good idea.”

Shallan frowned at the tone of his voice, then followed his gaze, to look at the thing Re-Shephir had been hiding. The pillar in the exact center of the room.

It was set with thousands upon thousands of cut gemstones, most larger than Shallan’s fist. Together, they were a treasure worth more than most kingdoms.

Oathbringer: The Stormlight Archive Book 3 copyright © 2017 Dragonsteel Entertainment, LLC