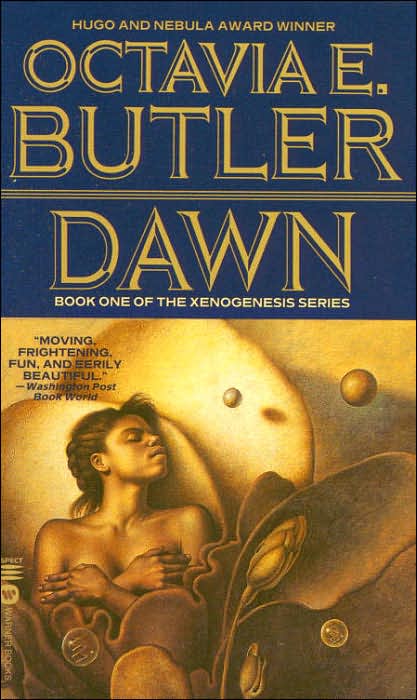

I first read Octavia Butler’s Dawn almost (oh, gods) 10 years ago for an undergraduate course called “Science Fiction? Speculative Fiction?” It is the first in the Xenogenesis trilogy which was republished as Lilith’s Brood. It is also a gateway drug. Dawn introduced me to the troubling and compelling universe of Butler’s mind, populated with complex, defiant, intelligent woman leaders, consensual sex between humans and aliens, and heavy doses of every social issue under the sun.

Dawn‘s Lilith Iyapo is a young black woman who awakens 250 years after a nuclear holocaust on an enormous ship orbiting Earth. The alien Oankali have rescued/captured the few remaining humans and begun regenerating the planet so it can again be habitable. These humanoid, tentacled higher beings intend to return the humans to Earth, but it wouldn’t be a Butler novel if there weren’t some sort of tremendous sacrifice involved. The Oankali are gene traders. They travel the galaxy improving their race by joining up with the races they encounter. They’ve saved humanity in order to fulfill their biological imperative to interbreed. Lilith will be a leader in one of the new human-Oankali communities on Earth. Her children will have fun tentacles. And she has no say in the matter. Lilith reacts to this with more than a little skepticism—she almost kills herself.

The Oankali manipulate her into training the first group of humans to re-colonize Earth. Lilith is a natural leader, but leading 40 angry, confused and captive humans is no easy task. Her loyalties are divided: On one hand she wants human freedom; on the other, she comes to respect and perhaps even love some of the Oankali. She develops a rewarding yet unequal intimate relationship with one of the Oankali ooloi (third sex). The relationships Butler creates defy categorization. Lilith is both mentor and enemy to the humans; lover, captive and defiant apprentice to the Oankali. Neither the humans nor the Oankali make this easier on her. The human community is hateful, violent and cruel. The Oankali are arrogant, careless and have no concept of human rights.

People claim that Butler is essentially pessimistic about humankind and that her perspective on the future is dystopian. Certainly the humans react to the Oankali with xenophobia and violence. Actually they share these tendencies with each other as well. The humans are none too keen on having a leader who appears to have allied herself with the enemy. The men are particularly threatened by Lilith’s strength and confidence. They beat her and call her a whore. They attempt to rape one of the other women. They respond to Lilith’s Chinese-American boyfriend Joe with bigotry and homophobia. The humans start a war with their alien captors. The Oankali are peaceful, environmentally responsible and relatively egalitarian. They’re just trying to save humanity, right? And look at the thanks they get.

Yet Butler isn’t interested in simple characterizations: Oankali good, humans bad. The Oankali don’t have a utopian society. They berate the humans for their deadly combination of intelligence and hierarchical thinking. Yet they constantly violate the rights of their captives, and their society has its own hierarchy among its three genders. Their forced interbreeding program looks a lot like the rape with which the humans threaten each other. Lilith is kept in solitary confinement for two years with no knowledge of who her captors are. When she’s released she has no control over her life. She is denied contact with other humans for a long time. At first the Oankali won’t allow her writing materials or access to some written human records they saved. And she discovers that they have destroyed the few ruins of human society, so humanity can “begin anew” with the Oankali. This sounds a lot like colonialism, slavery, internment camps take your pick. If Butler is showing her negativity about humanity, she’s doing it allegorically through the Oankali as much as she is directly through the humans.

However, I don’t think Butler was a misanthrope. As usual, I find a ray of hope in her work. There are redemptive characters among both the humans and the Oankali. While Lilith doesn’t regain her freedom, there is the possibility at the end of the novel that the other humans will. Lilith is coerced and manipulated, and her choices are extremely limited (interbreed, death or a solitary life aboard the ship). But she’s an intelligent, creative and strong-willed woman, and she does what Butler’s heroines do well: She negotiates between poor options. She reluctantly acts as the mediator between the humans and the Oankali. She isn’t willing to be an Oankali pet or a guinea pig, but she isn’t willing to revert to caveman society with the humans either. Throughout the novel she demands respect from the Oankali, and works to forge a more equal partnership between the two groups. The novel, as the first in a series, offers no resolution, only the assurance that our heroine is undaunted in her quest for autonomy, and that the possibility of transformation and progress exists for both species.

Erika Nelson is re-reading the entire Octavia Butler canon for her M.A. thesis. She spends most days buried under piles of SF criticism and theory, alternately ecstatic and cursing God.

“She negotiates between poor options.”

This, exactly. I am reading the trilogy for the first time right now and am dazzled at the way Butler continually undercuts your narrative expectations. She is a profoundly discomforting writer, which I think is one of her greatest strengths. Though they’re so dissimilar, she constantly reminds me of Iain Banks in her rigorous rejection of sentimentality.

I love Fledgling and the Seed to Harvest series, but I suspect Lilith’s Brood is her masterpiece. Of all her books I have read, it is most explicit about her constant theme: what the Oankali call The Contradiction. Humans are intelligent yet hierarchical. Coercion is both unbearable and inevitable. Sometimes all you can do is negotiate between poor options.

Having read Butler’s Kindred in a Afr-Amer. Lit. Class I cannot say how intrigued this book has me. I was gonna pick up another Ursula K. Le Guin, but it looks like a new femal science fiction writer might take her place.

Butler’s females heroines are powerful but don’t wreak of the “I can be a hero too” mentality that a lot of writers drench their female leads in. Butler makes her heroines, strong, realistic and mortal. Nobody suffers like a woman in a Octavia Butler novel.

Dawn made a Butler fan out of me. It has been a few years since I read it, but your review/synopsis made me think I should pick it up again, knowing that I am sure to enjoy it again and again.

I would agree that Xenogenesis is Butler’s masterpiece, though I enjoyed the Patternist series almost as much. Lilith and her family exhibit the best trait of humanity in there ability to navigate their circumstances.

I’ve recently discovered the work of Octavia Butler, starting with the Xenogenesis trilogy and then the Paternist series. At the monent I’m reading the Parable of the sower and though I don’t know (haven’t looked it up) which comes latest, I found the Paternist series to be pretty uneven, not having the same ‘draw’ that the Xenogesis trilogy has. If I would guess I’d say that the Parable books are written after that as her writing in those books is even more ‘capturing’/’immersive’/whatever (English as a second language here, grasping for words)

Anyway, I would recommend anyone to read her books, they have given me food for thought and held my attention as not many books have done in the past few months.

The fact that Octavia Butler is relatively so little known really sums up much of what is wrong with our world. I am a lifelong science fiction fan, but this woman knocks some of the established (male) ‘greats’ into a cocked hat.

I am almost at the end of the Xenogenesis trilogy and (having recently read both Parable books and Fledgling following my discovery of Butler’s work through Kindred) I am just ashamed that I hadn’t read the work of this truly great writer before. The themes are almost overwhelming in their complexity – pointed up by the stark, spare prose – and the emotional impact of the work simply grows and grows as the reader tries to take these themes in.

I would urge everyone to read this series because you will come back to it again and again in your mind. This book – this writer – will change your life.

Where is this thesis you spoke of?

Just finished reading dawn and boy it is simply exquisite, I love the simplicity of the tone which amazingly enough draws you in like poetry. It’s incredible that being an avid reader, an black woman, and an inspiring writer that I never even heard of this lady until I was in my 20s and that it took me this long to read her books and now that I have, I can’t get enough. The way she incorporates race relations, the aspects of imperialism, colonialism and slavery is impressive, the paternalistic aspect of the Ooloi, and the cognitive dissonance that exist is fascinating to read. Also fascinating is the justification of the Oankali’s desires to interbreed being a biological imperative and yet the Oankali have no objection on denying humans that same right. I could go on about the many contradictions and interesting perspectives but I would wound up writing an article or two. Point being, loved the book, about to read adulthood rites. It’s so sad that she passed away but if I could write half as well as her I would be very happy.

I do think the Oankali attitude towards humans can be explained by the fact that when they turned up humans had essentially genocide themselves due to racism, nationalism, and political ideology. They look at these h7mans and rightly conclude that if they saved them and let them continue as before, they’d just genocide themselves again. Humans are far lower down the technology and civilizational ladder than the Oankali. Sure the Oankali talk of trade, but trade benefits both parties, and they are trying to help humans survive. They see the best way to keep humans from auto-genocide is to revolve their destructive genetic traits. They do that because that is their natural way of thinking. Sure they make mistakes. But they aren’t invaders ir colonials because the world would be dead without them.