Since I started this column in 2019, I’ve been avoiding one famous—possibly even the most famous—example of using linguistics in SFF literature: the work of J.R.R. Tolkien. It’s not because I don’t like Lord of the Rings—quite the opposite, in fact. It’s just such an obvious topic, and one which people have devoted decades of scholarship to exploring. Hell, my Old English prof has published academic scholarship on the topic, in addition to teaching a Maymester class on the languages of Middle-earth. But I suppose it’s time to dedicate a column to the book that first made me think language was cool and to the man who wrote it.

Tolkien was born in 1892 in Bloemfontein, modern South Africa. His father died when he was 3, and his mother died when he was 12. He was given to the care of a priest and attended King Edward’s School, where he learned Latin and Old English, which was called Anglo-Saxon back then. When he went to Oxford, he ended up majoring in English literature, and his first job post-WW1 was researching the etymology of words of Germanic origin that started with W for the Oxford English Dictionary. This sounds both fascinating and utterly tedious, given the obvious lack of digitization at the time and thus the necessity to read and annotate print books to find and confirm sources.

Tolkien’s academic career began around the same time, and he worked on reference materials for Germanic languages (a vocabulary of Middle English and translations of various medieval poetry) before being named Rawlinson and Bosworth Professor of Anglo-Saxon at Oxford. Diana Wynne Jones attended his lectures and found them “appalling” because she thought that “Tolkien made quite a cynical effort to get rid of us so he could go home and finish writing The Lord of the Rings.” (Does the timeline match publication history? No, probably not, but this is what Wynne Jones remembered 50 years later.)

He was academically interested in the history of language: how words and grammar changed over time. He was focussed on English, but by necessity he had to know about other Germanic languages (German, Norwegian, etc.) in order to pursue etymological studies. This interest in dead languages carried with it an interest in translation, taking a poem from a long-gone society and bringing it to the modern reader (see my column on Maria Dahvana Headley’s Beowulf translation for more info on that).

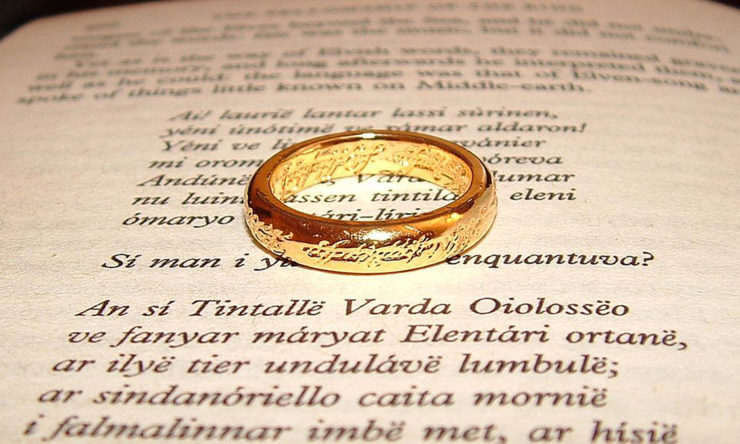

As a youth, Tolkien encountered invented languages first from his cousins, then moved on to making up his own a little later. He also learned Esperanto before 1909. If you put his academic interest in language history together with his nerdy interest in invented languages, you can see how he decided to invent an Elvish language and give it a history. And then develop distinct branches of that language and give them their own histories. And then come up with people (well, Elves) who spoke the languages and give them a history.

Tolkien set up the entire history of Middle-earth as a frame story, one based in the premise that he was publishing his own translations of ancient texts that he’d found. The frame is entirely unnecessary (and unless you read the appendices and prologue, you probably don’t know it exists), but the man was a giant nerd about language and translation, so it was completely obviously the thing he needed to do in order to tell this tale. Logically.

The prologue of LOTR, “Concerning Hobbits,” tells us that The Hobbit is a translation of a section of the Red Book of Westmarch, which itself started from Bilbo’s memoirs of his journey with the dwarves. The book, bound in plain red leather, has gone through multiple titles by the time Frodo adds his memoirs and passes it on to Sam:

My Diary. My Unexpected Journey. There and Back Again. And What Happened After.

Adventures of Five Hobbits. The Tale of the Great Ring, compiled by Bilbo Baggins from his own observations and the accounts of his friends. What we did in the War of the Ring.

Here Bilbo’s hand ended and Frodo had written:

The Downfall

of the

Lord of the Rings

and the

Return of the King

(as seen by the Little People; being the memoirs of Bilbo and Frodo of the Shire, supplemented by the accounts of their friends and the learning of the Wise.)

Together with extracts from Books of Lore translated by Bilbo in Rivendell.

Then the Appendices are all about the history of Gondor and the Elves, and transliteration notes and a discussion similar to what you’d find in the translator’s notes or introduction of a text, where they justify the various decisions they made, especially controversial ones. He had an idea, and he committed to it. That’s dedication.

Tolkien’s academic interest in Germanic languages, especially Old English, is most obvious in the Rohirrim. In the frame narrative, the language of the Rohirrim is unrelated to the language of Gondor (but is related to the Hobbits’ language, as noted when Théoden—or maybe it was Éomer—remarks that he can sort of understand Merry and Pippin’s conversation). Tolkien, as the translator of the RBoW for an English-speaking audience and as an Anglo-Saxon scholar, decided to use Old English to represent it. So the king is Théoden, which is an OE word for “king or leader,” from théod (“people”), and Éowyn is a compound word that means approximately “horse-joy.” The name they give themselves, Eorlings, contains the same eo(h)- “horse” root as Éowyn. Tolkien gives this as “the Men of the Riddermark.” Eorl is also the name of one of their early kings, much like the legendary Jutes who led the invasion of Britain in the 5th century were called Hengist and Horsa, both of which are words for horse (heng(e)st = stallion).

Let me tell you, when I was learning Old English, there were so many vocab words that immediately made me think of Tolkien and say appreciatively, “Oh, I see what you did there, old man. You nerd.” Because he used Old English to represent Rohirric, the songs of the Rohirrim in the text are in alliterative verse (again, see my column on Beowulf):

Out of DOUBT, out of DARK, to the DAY’S rising

I came SINGING in the SUN, SWORD unsheathing

To HOPE’S end I rode and to HEART’S breaking

Now for WRATH, now for RUIN and a RED nightfall!

The language of the Hobbits is a descendant of a Mannish language from the upper Anduin, which is related to that of the Rohirrim. The origin of the word Hobbit, which they call themselves, is “forgotten” but seems “to be a worn-down form of a word preserved more fully in Rohan: holbytla ‘hole builder’.” But later in the same Appendix F, he writes that hobbit “is an invention,” because the common tongue used banakil ‘halfling,’ and he based it on the word kuduk, used by the people in Bree and the Shire. This word, he writes, is probably a “worn-down form of kûd-dûkan,” which he translated as holbytla, as previously explained, and then derived hobbit as a worn-down form that would exist “if that name had occurred in our own ancient language.”

Tolkien used linguistics in an entirely different way than I’ve talked about in this column before. Rather than content himself with making up a few words here and there or doing just enough to give everything a veneer of truthiness, he constructed a whole-ass language (more than one!) and pretended that he was translating a book written in that language into modern English. When I was a wee baby writer (so, like, high school), I, too, wanted to create a similarly huge setting and a bunch of languages and so on. I eventually decided I didn’t want to put in that kind of immense effort but my interest in languages endured, and through a long, circuitous route I ended up getting an MA in (Germanic) linguistics while writing SF. And here we are!

So, what was your first exposure to Tolkien? Did you also try to learn the dwarvish runes and Tengwar? Did you make it farther than I did and actually learn them? Discuss in the comments!

CD Covington has masters degrees in German and Linguistics, likes science fiction and roller derby, and misses having a cat. She is a graduate of Viable Paradise 17 and has published short stories in anthologies, most recently the story “Debridement” in Survivor, edited by Mary Anne Mohanraj and J.J. Pionke. You can find her current project, a book on practical linguistics for writers, on Patreon.