In this bi-weekly series reviewing classic science fiction and fantasy books, Alan Brown looks at the front lines and frontiers of the field; books about soldiers and spacers, scientists and engineers, explorers and adventurers. Stories full of what Shakespeare used to refer to as “alarums and excursions”: battles, chases, clashes, and the stuff of excitement.

Today, I’m looking at a pair of planetary romance books by two masters of adventure tales. The first book is by Robert E. Howard, famed creator of the barbarian Conan, and is one of the rare tales where he takes his protagonists to another planet rather than into the distant past. And the second book is by Edgar Rice Burroughs, equally famed creator of Tarzan, John Carter of Mars, and others, and is set beyond our own solar system, in a planetary system that seems tailored to provide non-stop adventure.

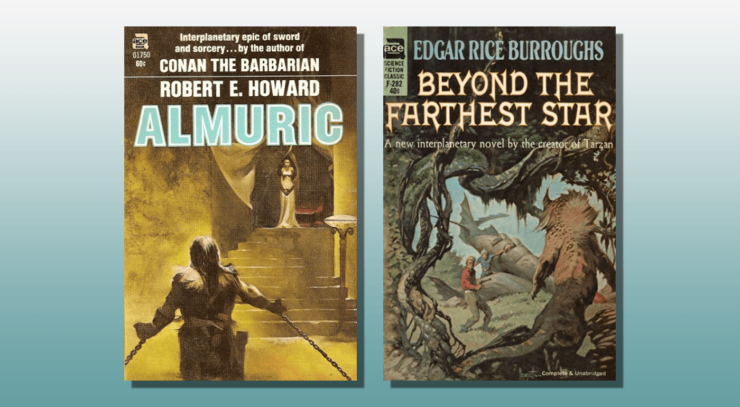

I found my copy of Beyond the Farthest Star a few years ago at my favorite used bookstore; it’s an Ace paperback from their seventh printing, published in 1979 with a cover by Frank Frazetta. It collects two related stories. The first story was entitled “Adventure on Poloda,” and originally published in Blue Book magazine in 1942, while the second, entitled “Tangor Returns,” was not published until years after Burroughs’ death, and copyrighted in 1964.

My copy of Almuric was published by Berkley Medallion Books in 1977, and while the cover painting is uncredited, it looks like the work of artist Ken Kelly. I am pretty sure I bought it when I lived in Sitka, Alaska, from a little bookstore across the street from the iconic Russian Orthodox Church in the center of town. It reprints a story that was first serialized in Weird Tales magazine in 1939, and first published in book form by Ace Books in 1964. There is some dispute regarding the authorship of Almuric, which was not published until after Howard’s death. Some speculate it may have been written by fellow writer Otis Adelbert Kline, Howard’s literary agent and an editor of Weird Tales magazine, or perhaps rewritten from an early draft or outline by Howard.

About the Authors

Robert E. Howard (1906-1936) was a Texan author who started his professional writing career at 18, and by 23 had become a full-time author. While largely known for his pioneering work in the sword and sorcery genre, he also wrote tales of suspense, adventure, boxing, horror, western adventure, and even planetary romance. I’ve reviewed Howard’s work before in this column, looking at his Conan tales here, and his Kull tales here, and there is more biographical information in those reviews. You can find work by Howard available to read for free at Project Gutenberg.

Edgar Rice Burroughs (1875-1950) was one of the most popular authors of the early 20th century, making an indelible mark on both science fiction and adventure fiction. I’ve looked at his work in this column before, including A Princess of Mars, the book Pirates of Venus and the rest of the Venus series, and also Tarzan at the Earth’s Core and the other Pellucidar books. All those reviews contain more biographical information on the author. You can find much of Burroughs’ work available to read for free at Project Gutenberg.

Planetary Romance Beyond Our Solar System

Planetary romance is a distinct sub-genre of science fiction, and was especially popular in the early days of the genre. While early space opera tales were often set in space, and spent a great deal of time describing how people got to other worlds, planetary romance was distinctive in skipping the journeys and moving the story directly to distant worlds, where the authors could imagine all sorts of exotic settings for adventures. During the golden era of planetary romance, the authors generally utilized the worlds of our own solar system, which were often imagined as having similar conditions to what we have here on Earth, especially a breathable atmosphere. Venus was depicted as hot and wet, Mars as cold and dry, and Mercury as tidally locked to the sun, with only a thin habitable region between its light and dark sides, but even asteroids were often described as having an environment where a spacesuit would not be required.

That consensus view of the solar system, however, collapsed in the era of robot probes beginning in the 1960s, which showed that the worlds around us were far stranger, and far less hospitable, than had previously been hoped.

The reaction of the science fiction community was for the most part to take planetary romances to planets that orbited other stars, which could still be imagined as earth-like worlds. A famous example of this is the Skaith trilogy by Leigh Brackett, who starting in 1973, sent her planetary romance hero John Eric Stark to a dying world orbiting a distant red sun (see my reviews here, here, and here). And she was not alone, as science fiction books that portrayed Earth-like worlds moved out to other stars.

Even before the era of robot probes, however, there were planetary romances set outside our solar system, including the two books under discussion today…

Almuric

The novel opens with a forward written by Professor Hildebrand, a scientist who has discovered a portal to a far-off world he calls Almuric. And it is through the professor’s eyes that Howard first describes Esau Cairn, a character right out of Howard’s boxing and contemporary adventure tales. Cairn is a powerful man who falls into the orbit of a corrupt political boss. When that boss tries to break Cairn, as he has broken so many others, Cairn kills him in a fit of rage. Hunted by the authorities, Cairn goes to Hildebrand for help and is sent through the professor’s portal, at which point the book shifts to a first-person narrative from Cairn’s perspective.

He finds himself naked on a grassy plain, and soon encounters a powerful warrior. They fight, Cairn knocks his opponent out with his powerful fists, and takes his knife, belt, loincloth, and sandals. Rather than fight others he sees approaching in the distance, Cairn heads into the nearby hills. He faces many fierce beasts, although the creatures are disappointingly similar to Earth beasts, with Howard not taking full advantage of having a whole new world to explore. Cairn thrives in this primitive environment, finding that its challenges stimulate him, and feeling more alive than he ever did on Earth. He finds a man being attacked by a large saber-toothed leopard, rescues him, and binds his wounds. But, pursued by others who misunderstand Cairn’s actions, he again runs for the hills. He learns to make fire, fully conquering his environment.

But Cairn is lonely, and approaches a nearby stone castle. He is shot by a primitive carbine and taken prisoner. He finds that he can understand his captors, although it is not clear whether they speak English, or if he understands their language through some unexplained mechanism. He finds that while the men of his world are large, shaggy, and barbaric, the women are small, slender, and beautiful. Cairn develops feelings for a woman named Altha. They recognize his dagger, but doubt his story that he won it from its previous owner in a fair fight, and force him to face one of their mightiest warriors in combat. When Cairn wins this and several other fights, he is accepted as a warrior of their tribe.

The common enemy of the warring humans of Almuric is the Yaga, a race of jet-black people with giant bat-like wings. Cairn is out hunting when he sees Altha, who has run away from home, and saves her from a giant beast, only to have them both be captured by the Yaga. They use the human women as slaves and food, and are intrigued by Cairn’s smooth skin. They take him to their queen, who is the only female Yaga who is allowed to keep her wings. This practice of female wing amputation is explained as a means used by the males to control the females, but that seems to clash with the fact that they obey a woman ruler, and the contradiction made my head spin. Cairn and Altha endure all sorts of trials and torture at the hands of the Yaga. As often happens in sword and sorcery tales, the queen develops feelings for Carin, and he uses his favored status to find out secrets about their fortress and escapes.

Cairn then unites the warring human tribes, and leads them against the Yaga. What follows is a headlong rush of battles—a bit too rushed, and lacking the vivid and evocative descriptions that usually bring action scenes to life in Howard’s work. While the book starts out with passages that feel like pure Howard, the rushed battle scenes and a jarringly sunny ending leads me to believe those who suggest that the story was finished by other hands.

Beyond the Farthest Star

Like many Burroughs tales, the story begins with a framing device, a typewriter that operates itself to tell the tale of an Allied aviator who dies in a dogfight with German fighters (although we are not offered any more information about his past, or even his name). He awakens, naked and alone, in a garden, to be discovered by a young woman dressed in a skintight outfit that appears to be made of red sequins. A group of men appear, dressed similarly but carrying sidearms, and take the protagonist prisoner (the scene reminds the reader of a similar encounter in Pirates of Venus…not the only time this book recycles ideas from previous Burroughs works).

The mysterious aviator is put in the hands of a psychiatrist, who gives him the name Tangor (which means “from nothing”), teaches him the local language, tells him he is on the planet Poloda, 450,000 lightyears from Earth, and eventually begins to believe his story that he comes from another world. Tangor volunteers to help Unis in their eternal battle with the Kapar, and is soon accepted into their air forces.

Burroughs describes an interesting world, gripped in endless war, where many live underground, and buildings on the surface retract into the ground when the enemy attacks. The entire economy is dedicated to the military effort, and those odd costumes are the only thing people wear in order to save resources. “It is war” is a fatalistic litany repeated by the inhabitants as they accept their fate, a depiction influenced by real-world events from the time Burroughs was writing the tale, where the world being drawn into another World War, with the carnage of the first still fresh in everyone’s minds. Tangor soon becomes a pilot, and a successful one, in aerial battles that dwarf anything he’d seen on Earth, featuring combatants numbering in the tens of thousands. Tangor is shot down twice and has to make his way through dangerous wilderness and neutral territory to return to safety.

And then the story shifts from aerial adventure to espionage. There is a woman who wants to defect to the Kapar, and tries to convince Tangor to join her. But Tangor goes to the authorities, who want him to play along in order to spy on a Kapar effort to develop a longer-range power transmitter that will allow trips to other worlds. It turns out Poloda is one of a number of worlds that are strung around its star in a torus of atmosphere. The Unis authorities think that fleeing to one of those worlds could break the cycle of endless war. While improbable from a scientific standpoint, this is a fascinating stage for further adventures, and you can see Burroughs laying the groundwork for a whole series.

Tangor accompanies the woman to Kapar, where the enemy are suspicious and imprison him. There are a lot of twists and turns, but he is eventually enlisted into their research effort, finds the secret of long-range power transmission, steals an experimental craft, and escapes back to Unis. The book ends here, and unfortunately, the series does as well. Burroughs soon thereafter volunteered to serve as a war correspondent, and after the war, failing health prevented him from writing further. We will never know what adventures Tangor might have had after this one.

Final Thoughts

Almuric and Beyond the Farthest Star are solid examples of planetary adventure, although neither takes full advantage of the possibilities of being set in a whole new solar system, on worlds that could have taken any form at all. Neither Howard nor Burroughs does much more than give us more of the same type of tales they had already been writing, but in a new setting. And now it’s your turn to chime in: If you’ve read these two books, or would like to discuss any work by Howard or Burroughs, here’s your chance to comment. And I’m always interested in hearing about other planetary romance stories you may have enjoyed.