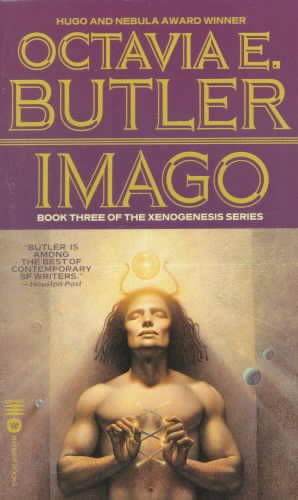

This post marks my third and final visit to Octavia Butler’s Lilith’s Brood. I’ve written about colonization, desire, transformation and negotiation in Dawn and Adulthood Rites. Imago ups the ante on all these, raising questions about identity and the performed self.

The human-Oankali breeding program begun a century earlier with Lilith and the events of Dawn reaches a critical turning point in Imago. To everyone’s surprise, one of Lilith’s hybrid children enters its adolescent metamorphosis indicating that it will become ooloi, the third sex. Jodahs is the first ooloi with genes from both species. Uncontrolled, flawed ooloi have the capacity to do massive genetic damage to everything they touch, and an ooloi with a human side poses even greater danger. Lilith and her family move to the deep woods to be isolated during Jodahs’ metamorphosis, awaiting possible exile on the Oankali ship orbiting Earth. Jodahs gains the ability to regrow limbs and change shape. But without human mates it’s unable to control its changes, and there is no chance of finding human mates on Earth before being exiled. Jodahs becomes isolated and silent. Beginning to lose its sense of self, it changes erratically with the weather and environment. Aaor, Jodahs’ closest sibling, follows suit, becoming ooloi. It then transforms into a sea-slug-like creature and nearly physically dissolves in its loneliness.

Wandering in the woods as a sort of lizard-creature, Jodahs discovers two siblings from an unknown settlement. Though the Oankali thought they had sterilized all humans on Earth who wouldn’t breed with them, the villagers are fertile on their own, thanks to one woman who slipped through the cracks. The inhabitants are inbred and diseased, but ooloi can heal anything. Jodahs repairs and seduces the pair, then returns with the ailing Aaor to find mates for it as well. The two young oolois’ trip to the resister village nearly ends in catastrophe as the siblings try to protect their human mates from hostile villagers. Like its mother Lilith and brother Akin, Jodahs becomes the diplomat between humans and Oankali, on which many lives depend.

Imago makes gender, race and species performative and malleable beyond even the first two novels. Seduction is easy for the siblings because they can become exactly their lover’s ideal of beauty, of any apparent race or gender, even concealing most of their Oankali features. Humans in the novel say that if the Oankali had always been able to shape shift, they would have had a much easier time drawing humanity into their breeding program. Even so, the humans still learn to accept difference — after all, the construct ooloi have scattered tentacles and four arms. With Jodahs’ peacemaking work, many of the resisters willingly (even eagerly) join Oankali families at the novel’s finale. The rest join the fertile, human-only colony that Lilith’s son Akin began on Mars in Adulthood Rites.

The two species have met each other half way. I don’t want to call this a utopian ending, exactly. The imbalance of power remains; the Oankali will always be stronger than humanity. Yet the alternative of the Mars colony puts the two species on more equal footing. While there are still some resisters on Earth, the reconciliation between the isolated village and the Oankali seems emblematic of the beginning of a truly hybrid race, characterized by consent and cooperation instead of coercion. Because of the construct siblings’ particular talents for physical transformation, seduction and verbal negotiation, they achieve something that would have been impossible in the first two novels.

The novel’s title certainly refers to the adult stage of insect development, hearkening back to Adulthood Rites‘ focus on Akin’s own adolescence. His metamorphosis, in which he transitions from a human to Oankali appearance, literalized his own struggle to be loyal to both sides of his heritage. These conflicts are repeated and complicated in Imago with Jodahs’ own metamorphosis and dual loyalties. While it loves its family and its Oankali ooloi parent in particular, it also knows Earth as home, and refuses to live on the Oankali ship. Like Akin it has to learn to reconcile this hybrid nature as it approaches adulthood. While Jodahs remains loyal to the Oankali, it also respects the humans’ need for autonomy, and chooses to maintain a human appearance and to live among them.

Yet the title also seems to refer to the siblings’ reliance on images, simulations and mimicry, their ability to reflect and embody both species. I would even venture that the title refers metaphorically to the imago dei, or at least to Butler’s notion of it. Humans from the village call the Oankali devils; Butler’s story suggests the opposite. Jodahs and Aaor’s shape-shifting echoes Butler’s Parable of the Sower and Parable of the Talents—and to an extent her story “The Book of Martha“—in which God is depicted as trickster and changer, that which molds and is molded by others. For Butler, adaptability and persuasion are next to godliness. These characteristics allow Jodahs to build effectively on the work of Lilith and Akin from the first two novels. Lilith enabled a painful, imbalanced integration with the Oankali. Akin created human separation and safety from their alien colonizers. With this foundation, Jodahs’ enables the two species to meet as something resembling equals. Jodahs’ physical changes are only the catalyst for more critical cultural changes it’s able to enact. The future for both species is not merely biological change, which has been obvious from the beginning of the series, but a progressively negotiated relationship moving closer to equality.

Erika Nelson is re-reading the Octavia Butler canon for her M.A. thesis. She spends most days buried under piles of SF criticism and theory, alternately ecstatic and cursing God.