In the late 19th century, Lord Acton penned the now oft quoted line, ‘power tends to corrupt, and absolute power corrupts absolutely.’ At the time, he was writing about how history should judge the actions of kings and popes, but it has been lifted for so many purposes that I think he won’t mind if I use it for an observation about fairytales—namely that these stories are extremely suspicious of power, and even more so of women wielding power.

To start with the obvious, there aren’t a lot of traditional fairytales where women hold any sort of real power. In most cases, like Sleeping Beauty or The Frog Prince or Rapunzel the main female character is there to be rescued or married, or more frequently rescued and married, and their power comes from being female and of course pretty. (This is not to say that there are not female heroes in traditional fairytales, but they are the exception and I want to reserve a discussion of them to a later post.)

More interesting, though, is that in those fairytales where women are permitted a measure of power, either terrestrial or magical, it is almost universal that they will wield the power for evil or will be corrupted by the power. I realize the same can be said of some male characters with power, the evil Rumpelstiltskin comes to mind as does the truly creepy king in Furrypelts—seriously he’s disturbed—but there are plenty of kings and charming princes that are allowed to be noble and good and all the rest. By contrast, in stories like Cinderella and Snow White—where a mother exists without a father or a queen without a king, and the women have power of their own, if over nothing else than at least over their household and the welfare of their daughters—women with authority tend to turn that power to evil. In Snow White the transformation is quite sudden, even instantaneous:

When the queen heard these words, she began to tremble, and her face turned green with envy. From that moment on, she hated Snow White, and whenever she set eyes on her, her heart turned cold like a stone.

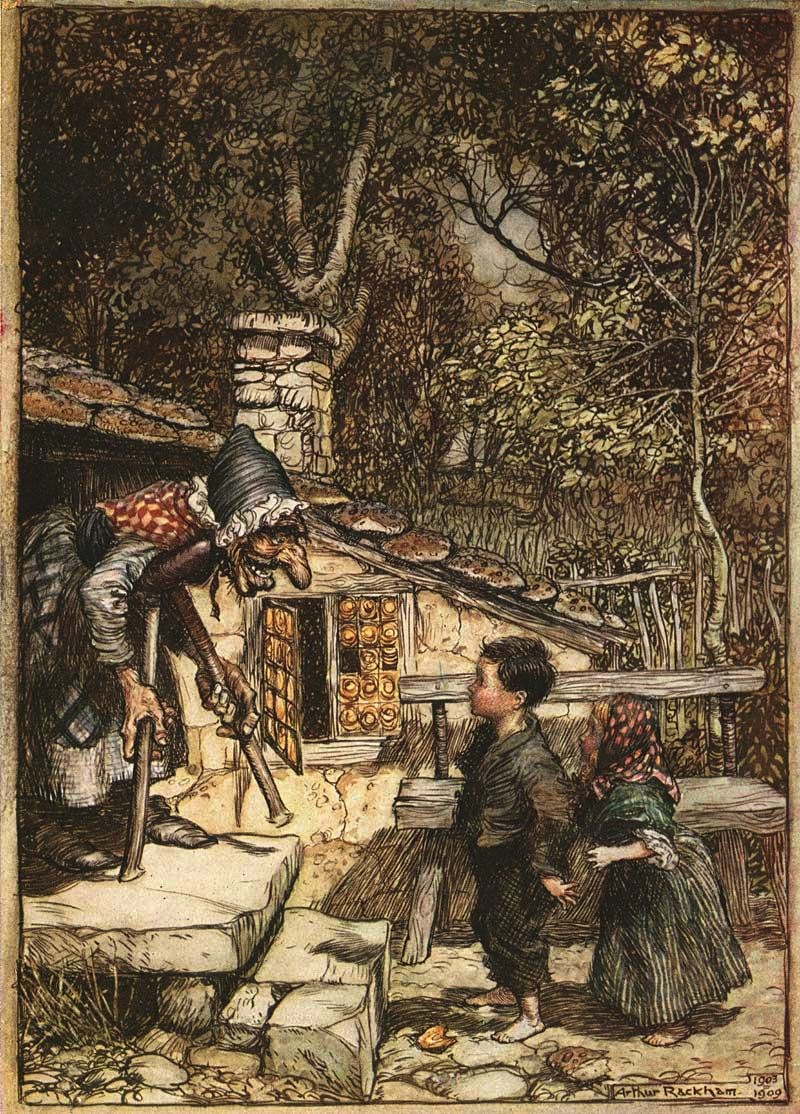

Likewise, in most stories where women are granted magical powers—Rapunzel or Hansel and Gretel would be good examples—the power is described in black terms, as witchcraft, and the women are in turn described as witches or hags. Take the description of the prototypical “wicked witch” from Hansel and Gretel,

Witches have red eyes that can’t see very far, but like animals, they do have a keen sense of smell, and they can always tell when a human being is around. When Hansel and Gretel got near her, she laughed fiendishly and hissed: “They’re mine! This time they won’t get away!”

A fantastic example of a fairytale that has a moral that seems to revolve entirely around the corrupting influence of power on women is The Fisherman and His Wife. In this story a fisherman catches an enchanted fish. Interestingly, the fisherman never asks the fish for anything, saying only, “Oh, ho! You need not make so many words about the matter; I will have nothing to do with a fish that can talk: so swim away, sir, as soon as you please!” It is only when he reports his encounter to his wife that she insists that he go and demand that the fish grant him a wish. Though the fish grants her wish, she is never satisfied always wishing for ever grander houses and titles until at last she asks for the impossible: to be God. At that everything is taken away and the fisherman and his wife are returned to the pigsty they were living in at the beginning of the story.

There are two points I find interesting:

First, that it is the person that makes the wish or uses the power that is corrupted. All along the way, even when the wish is actually quite reasonable (not to have to live in a pigsty for instance), the fisherman does not like the idea of imposing on the fish.

The Fisherman didn’t really want to go back, but he also didn’t want to irritate his wife, and so he made his way back to the shore.

Second, at every step of their improvement the fisherman is perfectly content, saying when first they receive a humble cottage, “Ah! How happily we shall live now!” Meanwhile, at every step the wife is less and less satisfied, and embodies the power of her new position, saying to her husband when she wishes to be not just king, but emperor, “I am king, and you are my slave; so go at once!”

Perhaps this is why so many scholars have written critically about the gender roles portrayed in fairytales. For example, Historian, Henal Patel writes,

In the end, the heroine is saved by a noble Prince and gets her happy ending because she is good. Perhaps ironically, the villain is also generally female. She is cunning and ambitious and, in most cases she is jealous and malicious. She will go to any means to achieve her end. As good as the heroine is, the villain is just as evil. These characters suggest if a woman shows agency and takes action, she is automatically evil. To be good, one must be docile.

Perhaps these gender norms are not surprising or troubling in these ancient tales, born as they were in a time and a place where ideas about men and women were fundamentally different from those the majority of people hold today. But, when I look at two very recent fairytale recreations, Frozen and Maleficent, I notice disturbing echoes of these old patterns.

Take Disney’s recent movie Maleficent, featuring the badass fairy Maleficent, a regular Dirty Harry of the fairy world. She stands, nearly alone, against the king’s army. She patrols the skies like an avenging angel. She kicks ass. But, she kicks ass as a warrior more than as a ruler or an enchanter. It is only after she is betrayed, and after she learns that Stefan has used her to become king, that she truly reveals and exerts the full measure of her power, and then in a moment she becomes evil. Initially, one might be able to forgive her desire for revenge, after all Stefan was cruel and he is well-deserving of whatever punishment Maleficent might devise, but Maleficent is not satisfied with retribution against the king alone. She curses Aurora, an innocent baby, and perhaps more troubling, she also punishes the truly innocent creatures of faerie. She installs herself as queen, creating by fiat a throne for herself where one had never before existed, and using her tree soldiers to forcibly subjugate the other creators of the realm—quite literally making them bow down before her. That she is redeemed in the end by her maternal instincts is not the point. The point is that her power corrupts her almost the instant she embraces it, and she must then spend the rest of the story attempting to undo all she has done with it.

Similarly, in Frozen Elsa is, nearly from birth, cursed by her power. In early scenes, when Elsa is shown playing with her sister, you can see her potential. Disney gives us the briefest of glimpses into the kind of joy she can create with her gifts, and yet despite her total innocence and the innocent purposes to which she puts her powers, she is not allowed to enjoy them. Almost at once the dark side of Elsa’s gifts are revealed, and she is not only forbidden to use them, she is forbidden even to interact with her beloved sister or to explain to her sister why they cannot be as close as they once were. Because of a power that was force upon her at birth, Elsa is physically and emotionally cut off from the rest of the world. She is even deprived of the comfort of human touch, having to, at all times, wear elbow length gloves lest she inadvertently reveal her true self to the world. And, needless to say, once she does decide that she can no longer conceal this central part of herself, and she actually uses her powers for her own purposes, she instantly plunges the rest of the kingdom into a deadly frost. Again, she is ultimately redeemed, but the redemption comes not in an acceptance of who she is or what her powers can do, as much as it does from her maternal instincts overcoming her earlier “selfishness” as she realizes that her love for her sister is more important to her.

I do not say that Frozen and Maleficent are not steps in the right direction. In both cases we have powerful women that manage to survive their stories more or less intact—at least they do not end up burned at the stake or rolled into a river in a barrel full of spikes. However, both stories still show a troubling tendency to punish women for exerting the full measure of their power, and both require for redemption that these women instead embrace their more traditional maternal sides. But then that is the marvel of fairytales, we can keep retelling them until we get them right. As Bruce Lansky wrote,

Nothing stays the same forever—especially if it doesn’t make sense. Take fairy tales, for example. I think you’ll agree with me that a princess shouldn’t have to marry a knight she doesn’t love (even if the knight does defeat a dragon), that no one can weave straw into gold, that no prince in his right mind would marry a princess who complains about a pea under twenty mattresses, and that the brave little tailor was actually a vain braggart.

Jack Heckel is the writing team of John Peck, an IP attorney living in Long Beach, CA who is looking forward to the upcoming release of Once Upon a Rhyme, and Harry Heckel, a roleplaying game designer and fantasy author, who is looking forward to the publication of Happily Never After.

I’m not sure I buy this. it seems to me that her redemption comes from the realization that fear lights the path to suffering, while love lights the path to joy.

Does her realization that her love for her sister is more important than <I’m guessing you are referring to her powers?> play a role in redeeming her from ostensible villiany? Even that seems a stretch – I don’t see anything to suggest that the general populace held a grudge against what was a scared child in a grown woman’s body. Once she is able to let her love for her sister overcome her fear of her power (even when she embraced them, she feared them – she had only let go of her fear of what others thought) she is able to wield total control.

At no point, however, do I see definably maternal instincts. Does she care about her sister? Sure? I care about my sisters, but I wouldn’t call my relationship with them maternal. Heck, I wouldn’t even say that about my relationship with my kids. And if someone called my relationship my spouse “maternal”, that would just be unnatural. “Familial instincts” seems a more appropriate phrase for both Elsa and for me.

I think the situation with Frozen and Maleficent is the result of a plot archetype that you have to be bad before you can be redeemed. Or in the words of the Stever Miller Band, you’ve got to go through hell before you get to heaven. If Campbell’s Hero’s Journey can be summed up as “good person learns to be a hero” then these stories can be summed up as “bad (or misunderstood) person learns to be good.”

Assuming that making the hero a women is a good thing, and further assuming (correctly) that making the hero(ine) both good and heroic from day one is boring, and then further assuming that the traditional hero’s journey has been done to death (from the very good Alice in Wonderland (2010) to the very bad Snow White and the Huntsman) I’m not sure what else is left besides the redemption angle. Which at least has the side-effect of making strong women victims of their own power, at least initially. Not sure how to overcome that.

I was totally with you until you got to the part about Frozen (I haven’t seen Maleficent and don’t really have a desire to, partially because I’m a bit weary of the whole ‘the villain is just misunderstood and the good guys were actually mean to them and it’s all their fault’ trope).

I had the exact opposite reaction you did to Frozen. In fact, I had some issues with that movie, but one of the things I really did like was that it was a bout a woman, with powers, who is ultimately allowed to KEEP her powers, and learns how to integrate them with her life and still have a sense of community – in other words, having power doesn’t mean becoming a villain or having to be isolated.

She’s not isolated/punished for her powers, but for losing control of her powers, which actually causes quantifiable harm. Some of this loss of control also comes out of fear (partially fed by the external fears of others), and yes, the excessive isolation was the wrong way to handle it (and I think we’re supposed to see it as wrong, and acknowledge that trying to isolate/punish women – or anybody else – with power/gifts is NOT the right way to go).

But ultimately, she is a woman who is allowed to be extraordinary, but that doesn’t mean she doesn’t bear some responsibility for her power. I also like the message that not all problems are solved with might/power. This is something all genders can/should learn. I think it’s cool they were able to do a story like this with a female protagonist.

Her redemption coming from “her maternal instincts overcoming her earlier “selfishness” as she realizes that her love for her sister is more important to her.” – you write this like this is some bad, oppressive thing that we should be horrified at encouraging in modern, progressive girls. It’s not. It’s a good thing. It’s what men AND women should aspire to; the issue I tend to see regarding these things and gender is that such things tend to be solely relegated to women (and enforced much more strictly/harshly in women), but to me the ‘fix’ is to start encouraging such things in men as well. Honestly, I think the song Let it Go is a villain song and not a song we should try to emulate (as awesome as it may be).

Edited – also, agreed to the poster who mentions ‘maternal’ isn’t even the right word to use here, nor did I see it as her making a choice between her powers and her sister. And, what is with the implication that being ‘maternal’ is bad or weak or something we need to move past as women, anyway? I’ll be honest, I don’t know one way or the other if women are more generally predisposed to be ‘maternal’ or not, based on their biological/neurological makeup, or just socially. But even if they were (and of course it’s just general and there are men and women all over the spectrum), I don’t think that’s bad, and I take the point of view that it just means it’s something we – people of all genders – can all learn from and try to follow as an example (and I myself am one of the outliers in that I am not naturally very maternal, but my husband is).

I second everything LisaMarie said above (thank you so much for eloquently addressing “Why are we treating traditionally feminine virtues as something to get rid of, rather than as something to encourage in everyone?”)

In Frozen, couldn’t we see the whole movie as an exploration of the consequences of people buying into the “Women With Power Are Bad” trope? Elsa has power, and her parents automatically treat that as something evil and fearful–which directly leads to Elsa acting fearful, losing control of her power, etc. The way I saw it, the movie makes it pretty clear that her bad actions aren’t the result of her powers, they’re the result of how her family treated those powers. And once everyone’s arrived at the moral of Love Fixes Everything, and once she learns to have full control over her own power, everyone gets to celebrate that. She makes a public ice rink, it’s hard to get more innocuous than that.

As a friend of mine mentioned, in both Cinderela and Sleeping Beauty, the fairy godmothers are female, have power and use it for good and to defend the kingdom.

I missed the part where Elsa actually did anything evil. Sure some of the things she did had terrible consequences but she never did anything through malice, just accidents and reactions that she did not see and could not foresee. It was fear of making things worse that prevented her from trying to fix things once she became aware of them.

you write this like this is some bad, oppressive thing that we should be horrified at encouraging in modern, progressive girls. It’s not

If you will forgive me for getting political, that is exactly what a certain strain of modern feminism argues. The person who wrote “A woman needs a man like a fish needs a bicycle” was clearly not thinking about 18+ years of child rearing. The same people who respect a woman’s choice to abort but don’t respect her choice to quit her job and stay home raising kids. Not all women who identify as feminists believe that of course, that viewpoint seems to be concentrated among coastal white highly educated liberal women. But it’s there.

An interesting piece — but I think you’re conflating 3 seperate kinds of power that really can’t be analysed together. Let’s call them Internal Power, External Power and Super Power.

Internal Power: Confidence, competence, self-acceptance, strength of will. Positive traits, that should be treated as such — though they do need to be well-written. Confidence can easily be written as smugness and hostility — as seen in the 90s “Strong Independent Woman” archetype — and strength of will should not preclude vulnerability — a problem seen in many male heroes who can only be truly hurt through a refridgerated female proxy, creating the impression that vulnerability and trauma are inherently female things. The treatment of internal strength as a moral negative among women, with positive women being pliant and timid, is definitely a problem in fairytales — though less so now, and it should diminish as well-written strong, female characters filter into our cultural landscape.

(That said, not all protagonists need internal strength — weak characters can be extremely interesting, and weakness should not be treated with contempt.)

External Power: Power over others, power within a hierarchy. Power that corrupts, power that the corrupt seek, power that the children of the powerful are taught is theirs by right. The power of bullies. Power that our stories should always be critical of, whether it is held by a man or a woman — the problem with fairytales is not the evil queen, it’s the noble king and the charming prince. Not that the powerful are always evil — some of them may be perfectly nice, and may use their power for good, to the extent that they can — but their power is always unjust, is typically based on the threat of violence and starvation, and they will almost always fight to defend it.

Super Powers: Extraordinary abilities and skills. Can be a metaphor for talents or minority status, can simply be there to make everything more awesome and epic, can act as a flexible plot-engine. The “oh no, my powers are exploding!” story is definitely the last kind, and it is troubling how much more common it is with female characters than male (the Dark Phoenix Saga, Frozen, Dark Willow, Doctor Who’s series 4 finale, etc.). That said, Frozen plays it very differently — it’s the fear of her powers that causes them to explode, not the powers themselves; at the end, she embraces her powers rather than being punished for them; definitely an improvement on the traditional narrative.

The Evil Witch also typically falls into the “plot engine” category, and again, the fact that Witches are typically evil and Wizards typically good is deeply problematic, though this is largely restricted to fairytales and their adaptations — modern witches are typically no different from wizards, with either being evil only when they use their Super Powers to gain power over others: External Power. This, I believe, is what happens in Maleficent — it isn’t that power corrupts her; she seize’s power because she is corrupted. And that — assuming power over others because one can — is bad.

See, the problem is that by conflating External Power with Internal Power (which is positive) and Super Powers (which are neutral, but awesome) you make it sound like External Power is a great thing just because sometimes, women can have it. Sure, as long as hierarchy exists, it shouldn’t favor one gender over the other — but even if it doesn’t, that doesn’t make it okay. It’s a problem that identity-politics can often fall into; by focusing solely on power imbalances between sexual or racial groups, you can imply that the power structure itself is justified but for those imbalances — that if inequality and injustice affected white men as much as black women, it would be fair and just. This is rarely the intent, but it is a troubling implication. The existence of black slaveowners in the American South did not make slavery just, nor should they be held to be admired as Powerful African-Americans who managed to succeed in a racist world. Their Power — to buy and sell humanity — was every bit as terrible as it was in the hands of white folk.

The true injustice — the one that makes the others possible, that creates them then uses them to justify itself — is the inequality between those who have (External) Power and those who don’t. Other inequalities matter, and need to be fought, but that shouldn’t lead us to celebrate such Power just because it is held by someone who wouldn’t normally get a chance. Stories should not treat Powerful Women worse than Powerful Men, but both should be treated critically.

I think you’re ignoring a whole class of women in traditional fairy tales to make your theory work. In many of the tales I’ve read, the heroine has someone looking out for her, and it is often a fairy godmother or and old woman they’ve helped or a dead mother. They all have a magical power, mothers most often the power of love and goodness, and use it to protect and to help their charge gain her wishes and overcome evil. What makes one set of women evil and the other good is what makes all characters good or evil, what they value, what they strive for, and how they go about getting it.

Comment posted twice.

^ As it is in stories, so it is in life.

Note that in the pre-modern and Early Modern societies the folk tales came from, our sort of radical individualism was not present. Wasn’t even really imaginable.

Eg., it makes perfect sense to curse your enemy’s descendants if you think of them (and yourself) as being very much the incarnation of a bloodline rather than a discrete free-standing individual. The whole institution of the vendetta and the blood feud were based on this. Y from Family X kills your uncle, you kill his cousin.

It’s more like two nations fighting than two individuals having a spat, in our terms.

Keep in mind how power was exercised in the societies in question; largely by inheritance and largely in a face-to-face personal manner, rather than through bureaucratic mechanisms. Power meant an immediate, personal assumption of obedience and ritual deference from a concrete human being, and would probably be punished immediately if withheld.

The metaphor for authority was familial, the household, rather than a machine or organization.

It could be exercised well or badly, but it would exist. This is why things like dynastic legitimacy were so important. Someone who’d break the rules to acquire power would probably be unpleasantly ruthless even by the standards of the day.

Also, while women usually (but not always) had less power than men of equivalent social status, they most certainly had power over men (and women) of lower standing. A peasant man would treat a noblewoman as a superior, or he’d suffer for it.

I want to start by acknowledging the many very insightful comments this article received. Since we began writing The Charming Tales, I have been studying and reading fairytales, and I think this issue of power and its representation in fairytales is fascinating. I will be exploring other aspects of morality and femininity in upcoming articles I hope to also be able to release through the Tor website.

It seems that the point that most commentors disagree with me about is in my analysis of Disney’s Frozen. I want to start by repeating what I hope came out in the article, that I’m a huge fan of the movie, and I do believe that it is a major step forward in how we formulate and tell tales about women and girls. However, I am judging it, not against other fairytales, like Snow White or Cinderella, but against its source material, Hans Christian Andersen’s Snow Queen. It is in that comparison that I find fault. I think had Disney simply taken the original Snow Queen tale and made a cartoon movie out of it, I would have been happier.

First, Snow Queen is a truly fascinating tale told in seven parts, and though it has many of the elements common in Anderesen tales like redemptive Christianity and rebirth, in some ways it is very subversive. In particular, in how it portrays women. Andersen’s Snow Queen revolves around a female protagonist, Gerda (which Disney kind of transforms into Anna), and her quest to rescue her playmate, Kai (a boy that is really eliminated from Disney’s version), from the Snow Queen (who Disney sort of transforms into Elsa).

Here we have the Snow Queen who is a true villian in the traditional sense (she kidnaps Kai) and set against her is our hero, Gerda, and a host of female helper characters including Kai’s wise grandmother, a female crow who helps her sneak into a palace, a princess that takes the unheard of position that she will only marry a prince as intelligent as herself, and a robber’s fearless knife wielding daughter who defies her family to free Gerda. (As an aside, Snow Queen also proves that you can have a great story about a Gerda without there being a need for a Kristoff.)

Anyway, there are so many fascinating female characters, and though Gerda is revealed to have power, she is never punished for it, but is allowed to use her power throughout the tale without consequence. Here is a quote from the sixth part of the Snow Queen when the reindeer Gerda is travelling with begs a woman they met to give Gerda power to fight the Snow Queen.

There is no need in this story for Gerda to overcome her powers or learn to love herself or not to fear her own agency. She is allowed the freedom to enjoy agency and power because of her innocence and because her cause is just.

Compare this to Elsa’s story.

Why does Elsa have to learn to fear her powers when her use of them is benign to begin with? If Elsa really was the evil Snow Queen then what follows and the lessons she learns would be justified, but she isn’t. She is not a villain, and her use of her powers is never villainous, and yet she is put through a classic villain character arc.

Is it such a bad thing that she goes off and build’s her castle in the mountains? Perhaps it is a little selfish, but who could not allow that Elsa, after so many years of isolation, deserves a release. It is a natural human desire to test the limits of ourselves, and yet she is not allowed this freedom, even though she takes precautions to isolate herself far away to avoid hurting people.

Is it really love for her sister overcoming her fear that allows her to control her powers? This would seem to suggest that she did not love her sister earlier in the story, or did not love her sister enough. I don’t buy this. If all it took was love to control her powers then she should have been able to control them, at least with respect to Anna, from the beginning. (By the way, I still maintain that by the coronation scene the relationship between Elsa and Anna is more parental that sibling. Elsa in those scenes acts like a classic parentified child.)

I definitely think Frozen is an interesting case, and this discussion makes me want to watch it again (for the dozenth time) to see if I really am missing the point. Still, in the end, I could wish that, in at least some respects, Frozen followed the script laid down by the Snow Queen a little more closely.

Thanks again for the comments.

Very interesting – I read Snow Queen years and years ago in a book of HCA fairy tales but don’t recall any of the details. So, I never thought about it when watching the movie. However, I think it may be unfair to do the comparison. Disney is notorious for only loosely based on it source material (such as one of my favorites, Hunchback of Notre Dame, and when they made Jungle Book, Walt Disney specifically told his people not to read the book).

From what I understand (this could be hearsay), they were initially going to go with a more close rendition. Elsa was going to be a villain, and Let it Go was going to be a true villain song and the start of her descent. But after hearing the performance of it, they decided to take her a different path. Which, in some ways I find more interesting, because it avoids the ‘woman with power=villain’ trope.

I am not sure it is love for her sister specifically – and I don’t think ANYBODY is suggesting that Elsa stopped loving her. But it’s a kind of ‘love casts out fear’ thing. I really didn’t see her arc as villianous at all, but for me the story resonated a lot, because I have been (in the past) the type of person to isolate myself or being afraid to let myself love people. So I think that is more Elsa’s issue – that, and a fear of herself which she should not have had (again, something I think the movie is pointing out. I don’t see her as being punished for her power because she was a villain, but rather she is coming to terms with her own fears. The movie is not approving of that punishment).

Ultimately the movie is less a ‘quest’ movie about a cause like the Snow Queen, but a movie about relationships. At least that’s how I see it.

To clarify, my problem with Let it Go wasn’t just the isolation, but more about her declaration that she’s above right and wrong. Which, if she kept going down that path, WOULD be villainous.

I actually do agree with you about Kristoff to an extent though. They subvert the ‘love at first sight’/’true love =romantic love’ thing just to have Anna end up with somebody else at the end. Except…I like Kristoff, haha, and I’m kind of a sucker for romance. And in general I think relationships are a good thing and it’s natural we like to see people paired off so I’m not going to get too upset over it.

I think we need to look further back than the Brothers Grimm and their contemporaries. The struggle is between the essentially and overwhelmingly patriarchal powers of Christianity (the priests and potentates of all flavors) who saw their largely matriarchal Pagan opponents as evil and threatening to their power. The first task of the Christians was to eradicate any semblance of matriarchal power or influence and establish the supremacy of the church and its patriarchs as the supreme rulers and relegating only subservient roles to women. You can see it today in the structure of the Catholic Church, not one position of any influence is occupied by women, and any attempts by the women of that faith to change that structure are strongly beaten down.

Because the churches of the middle ages were the repositories of knowlege and literature, only the naratives that support their outlook have survived. References to women legitimately wielding power have been systematically culled from our culture and any woman usurping power were persecuted to oblivion (see Joan of Arc). You can see the modern equivalent in the Republican paranoia with Hillary Clinton heading to possible power in the White House.