In the late 19th century, Lord Acton penned the now oft quoted line, ‘power tends to corrupt, and absolute power corrupts absolutely.’ At the time, he was writing about how history should judge the actions of kings and popes, but it has been lifted for so many purposes that I think he won’t mind if I use it for an observation about fairytales—namely that these stories are extremely suspicious of power, and even more so of women wielding power.

To start with the obvious, there aren’t a lot of traditional fairytales where women hold any sort of real power. In most cases, like Sleeping Beauty or The Frog Prince or Rapunzel the main female character is there to be rescued or married, or more frequently rescued and married, and their power comes from being female and of course pretty. (This is not to say that there are not female heroes in traditional fairytales, but they are the exception and I want to reserve a discussion of them to a later post.)

More interesting, though, is that in those fairytales where women are permitted a measure of power, either terrestrial or magical, it is almost universal that they will wield the power for evil or will be corrupted by the power. I realize the same can be said of some male characters with power, the evil Rumpelstiltskin comes to mind as does the truly creepy king in Furrypelts—seriously he’s disturbed—but there are plenty of kings and charming princes that are allowed to be noble and good and all the rest. By contrast, in stories like Cinderella and Snow White—where a mother exists without a father or a queen without a king, and the women have power of their own, if over nothing else than at least over their household and the welfare of their daughters—women with authority tend to turn that power to evil. In Snow White the transformation is quite sudden, even instantaneous:

When the queen heard these words, she began to tremble, and her face turned green with envy. From that moment on, she hated Snow White, and whenever she set eyes on her, her heart turned cold like a stone.

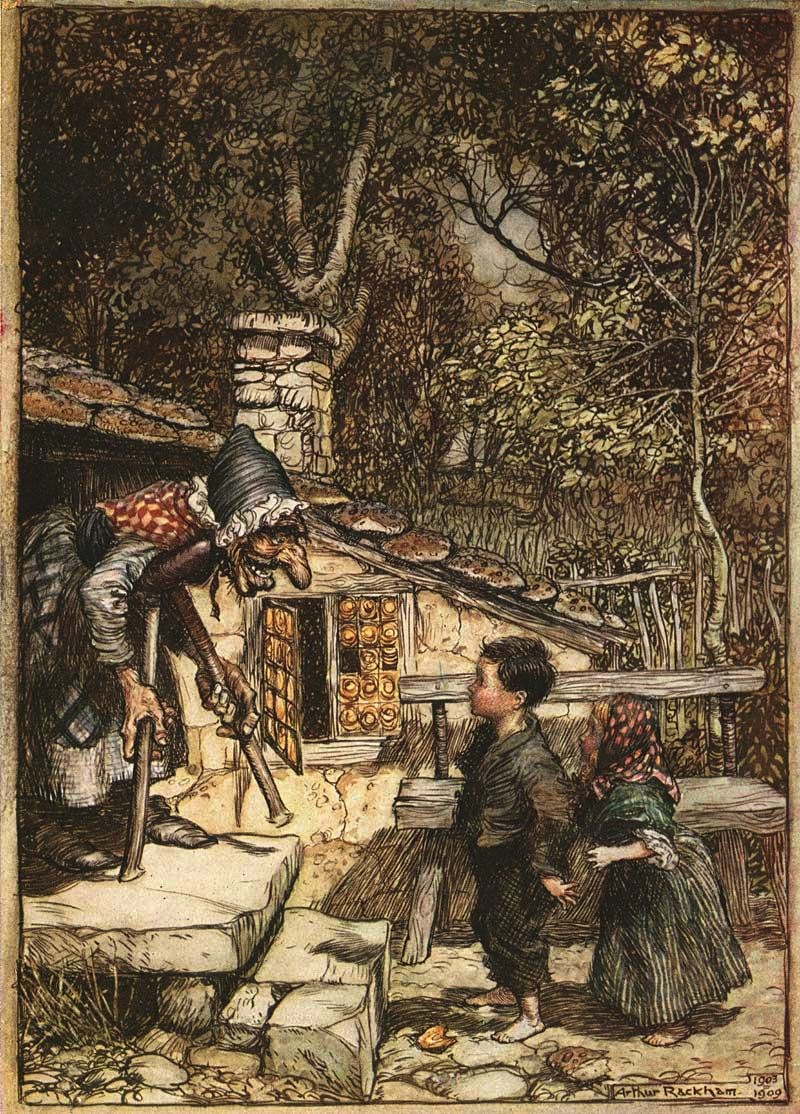

Likewise, in most stories where women are granted magical powers—Rapunzel or Hansel and Gretel would be good examples—the power is described in black terms, as witchcraft, and the women are in turn described as witches or hags. Take the description of the prototypical “wicked witch” from Hansel and Gretel,

Witches have red eyes that can’t see very far, but like animals, they do have a keen sense of smell, and they can always tell when a human being is around. When Hansel and Gretel got near her, she laughed fiendishly and hissed: “They’re mine! This time they won’t get away!”

A fantastic example of a fairytale that has a moral that seems to revolve entirely around the corrupting influence of power on women is The Fisherman and His Wife. In this story a fisherman catches an enchanted fish. Interestingly, the fisherman never asks the fish for anything, saying only, “Oh, ho! You need not make so many words about the matter; I will have nothing to do with a fish that can talk: so swim away, sir, as soon as you please!” It is only when he reports his encounter to his wife that she insists that he go and demand that the fish grant him a wish. Though the fish grants her wish, she is never satisfied always wishing for ever grander houses and titles until at last she asks for the impossible: to be God. At that everything is taken away and the fisherman and his wife are returned to the pigsty they were living in at the beginning of the story.

There are two points I find interesting:

First, that it is the person that makes the wish or uses the power that is corrupted. All along the way, even when the wish is actually quite reasonable (not to have to live in a pigsty for instance), the fisherman does not like the idea of imposing on the fish.

The Fisherman didn’t really want to go back, but he also didn’t want to irritate his wife, and so he made his way back to the shore.

Second, at every step of their improvement the fisherman is perfectly content, saying when first they receive a humble cottage, “Ah! How happily we shall live now!” Meanwhile, at every step the wife is less and less satisfied, and embodies the power of her new position, saying to her husband when she wishes to be not just king, but emperor, “I am king, and you are my slave; so go at once!”

Perhaps this is why so many scholars have written critically about the gender roles portrayed in fairytales. For example, Historian, Henal Patel writes,

In the end, the heroine is saved by a noble Prince and gets her happy ending because she is good. Perhaps ironically, the villain is also generally female. She is cunning and ambitious and, in most cases she is jealous and malicious. She will go to any means to achieve her end. As good as the heroine is, the villain is just as evil. These characters suggest if a woman shows agency and takes action, she is automatically evil. To be good, one must be docile.

Perhaps these gender norms are not surprising or troubling in these ancient tales, born as they were in a time and a place where ideas about men and women were fundamentally different from those the majority of people hold today. But, when I look at two very recent fairytale recreations, Frozen and Maleficent, I notice disturbing echoes of these old patterns.

Take Disney’s recent movie Maleficent, featuring the badass fairy Maleficent, a regular Dirty Harry of the fairy world. She stands, nearly alone, against the king’s army. She patrols the skies like an avenging angel. She kicks ass. But, she kicks ass as a warrior more than as a ruler or an enchanter. It is only after she is betrayed, and after she learns that Stefan has used her to become king, that she truly reveals and exerts the full measure of her power, and then in a moment she becomes evil. Initially, one might be able to forgive her desire for revenge, after all Stefan was cruel and he is well-deserving of whatever punishment Maleficent might devise, but Maleficent is not satisfied with retribution against the king alone. She curses Aurora, an innocent baby, and perhaps more troubling, she also punishes the truly innocent creatures of faerie. She installs herself as queen, creating by fiat a throne for herself where one had never before existed, and using her tree soldiers to forcibly subjugate the other creators of the realm—quite literally making them bow down before her. That she is redeemed in the end by her maternal instincts is not the point. The point is that her power corrupts her almost the instant she embraces it, and she must then spend the rest of the story attempting to undo all she has done with it.

Similarly, in Frozen Elsa is, nearly from birth, cursed by her power. In early scenes, when Elsa is shown playing with her sister, you can see her potential. Disney gives us the briefest of glimpses into the kind of joy she can create with her gifts, and yet despite her total innocence and the innocent purposes to which she puts her powers, she is not allowed to enjoy them. Almost at once the dark side of Elsa’s gifts are revealed, and she is not only forbidden to use them, she is forbidden even to interact with her beloved sister or to explain to her sister why they cannot be as close as they once were. Because of a power that was force upon her at birth, Elsa is physically and emotionally cut off from the rest of the world. She is even deprived of the comfort of human touch, having to, at all times, wear elbow length gloves lest she inadvertently reveal her true self to the world. And, needless to say, once she does decide that she can no longer conceal this central part of herself, and she actually uses her powers for her own purposes, she instantly plunges the rest of the kingdom into a deadly frost. Again, she is ultimately redeemed, but the redemption comes not in an acceptance of who she is or what her powers can do, as much as it does from her maternal instincts overcoming her earlier “selfishness” as she realizes that her love for her sister is more important to her.

I do not say that Frozen and Maleficent are not steps in the right direction. In both cases we have powerful women that manage to survive their stories more or less intact—at least they do not end up burned at the stake or rolled into a river in a barrel full of spikes. However, both stories still show a troubling tendency to punish women for exerting the full measure of their power, and both require for redemption that these women instead embrace their more traditional maternal sides. But then that is the marvel of fairytales, we can keep retelling them until we get them right. As Bruce Lansky wrote,

Nothing stays the same forever—especially if it doesn’t make sense. Take fairy tales, for example. I think you’ll agree with me that a princess shouldn’t have to marry a knight she doesn’t love (even if the knight does defeat a dragon), that no one can weave straw into gold, that no prince in his right mind would marry a princess who complains about a pea under twenty mattresses, and that the brave little tailor was actually a vain braggart.

Jack Heckel is the writing team of John Peck, an IP attorney living in Long Beach, CA who is looking forward to the upcoming release of Once Upon a Rhyme, and Harry Heckel, a roleplaying game designer and fantasy author, who is looking forward to the publication of Happily Never After.