I was a sophomore in college when my grandfather died. He was a good man—82 years old, a trumpeter, soft-spoken and kind. He slipped on an empty Coke bottle getting into his car one day; he hit his head on the curb, passed out, and never woke up again.

I went down to Chicago to be with my family for his shivah. Shivah is the seven day mourning period in Judaism immediately following the burial of a close family member. Mostly the observance consists of scrupulously doing nothing— opening a space to reflect, to process, to be with the loss. It’s a long spiraling week of almost entirely unstructured time: there are regular prayers, but even mealtimes grow wishy-washy as the leftovers cycle in and out of the fridge.

And this, after all, is the point. Without distractions, thoughts turn naturally toward the departed. People reminisce. Anecdotes are traded, and the family history that might otherwise have been forgotten starts to bubble up to the surface. We found some interesting things in the boxes and closets: naturalization documents, yearbooks, war letters.

What most interested me at the time, though—what I still think about today—was a thick photo album, full of curling-cornered prints and washed-out color. I remember flipping through it on the couch during that shivah, tracking the family resemblance. Press clippings, informal groupings: my father’s disinclination to smile seemed to run back at least as far as the mid-’60’s. There were pictures of a vacation home in Union Pier on Lake Michigan, and my Dad pointed out his own grandfather—a grocer upon whose monumental onion sacks he played as a boy.

At the very back of the album, though, there was a photograph that no one could recognize. It was thick, printed on card, the kind of thing that hasn’t been produced in a hundred years.

In the picture, a man in a boxy yarmulke with a wild growth of beard stared directly at the camera. There were no markings on the back to confirm my suspicions, but I was convinced that he was a member of our family. The resemblance was there: the full lips and almond-shaped eyes, the expression just a bit more severe than I suspect he’d intended.

Given what we know about the timing of our family’s arrival in this country, it seems likely that someone carried that print with them across the ocean, but I still don’t know who the man was. Years later when I began my own family, I indulged in some light genealogical research, but by that time, the photo album had been mislaid. I have some guesses now—a thin thread of names and dates that I try from time to time to hang that memory upon.

But the 20th century has proved to be something of an insuperable obstacle on my path back into the past. Records in the Old Country were made not only in a language I don’t know, but in a different alphabet as well, and anyway, they were most often kept in church registers, where there’s no mention of the Jews. My grandfather’s father (Hirschl by birth, Harry by assimilation) was born in the little village of Hoholiv, Ukraine; these days, judging from their website, there’s no memory that Jews were ever even there.

It’s hard to exaggerate the cataclysmic havoc that the 20th century spilled out on the Jews of Eastern Europe. The Holocaust, of course, is the ready example—millions of lives and a millennium of mimetic culture gone in just a handful of years. But Jewish Eastern Europe began the century on the back foot: hundreds of years of legalized oppression and popular violence in the Russian Empire culminated in a thick wave of pogroms—state sanctioned Jew massacres—that had already set off a major tide of emigration in the waning years of the 19th century. And if the beginning and middle of the 20th century didn’t go well for the Jews of Eastern Europe, then the end was hardly any better—the Soviet regime criminalized the practice of Jewish religion and invented spurious charges with which to sweep up those interested in preserving any hint of secular Jewish culture.

At the end of the 19th century, there were more Jews in Eastern Europe than anywhere else; by the end of the 20th, the largest body of Jews in the world had been decimated in human and cultural terms. Thankfully, neither Hitler nor Stalin managed to wipe out our culture entirely—the descendants of Ashkenazi Jews make up roughly 80% of the world’s Jewish community today, and when we fled to safer shores, we brought our language, our food, our books with us.

I, however, am more concerned with the things that didn’t make the crossing.

There were many—all the secret recipes, all the art and artifacts. An entire architectural style was lost: the wooden synagogue, often highly figured and beautifully adorned. Perhaps a handful of examples remain in the world, and most of them are replicas.

If it was Jewish and it could burn, then they burned it.

I mourn the loss of the synagogues, of course, of the artifacts and recipes, but in the end, I am not an architect, or a chef. I’m a writer of fantasies.

What keeps me up at night is the loss of Jewish magic. And I mean this literally.

It’s sometimes hard to communicate to non-Jews the degree to which Jewishness is not just a religious identity. Founded as a nation roughly three thousand years ago, before the concepts of ethnicity, worship, and nationality were tidily separable, we are a people—a civilization more than anything else. The most traditionally observant Jews will persist in identifying people born to Jewish mothers as Jews even as they practice other religions and renounce the Jewish God. There are even Jewish atheists—a lot of them.

Our religion is submerged, then, in a thick broth of associate culture, and that’s why, despite the fact that the Hebrew Bible clearly prohibits the practice, we can still discuss Jewish magic just as easily as we can discuss Jewish atheism: it’s very clearly there.

From the ancient Near Eastern making of incantation bowls to the still-ongoing practice of leaving petitionary notes at the graves of sages, Jews have been practicing magic as long as we’ve been around. In some times and places, Jewish magic has been codified, elevated into theology and philosophy. Traces of this tendency exist in the Talmud, and notably in the various phases of Kabbalistic development throughout our diasporic history.

But these are the kinds of Jewish magic that haven’t been lost; anyone with a library card or an internet connection can find out about them. What I mourn is the loss of folk magic—the stuff too quotidian, too obscure, perhaps even too heterodox to have been recorded. We know it was there. We see traces of it in rabbinic responsa as well as secular literature: the way our grandmothers used to tie red thread to our bassinets in order to keep the thieving demons away; the way our grandfathers used to appeal to the local scribe for a protective amulet of angels’ names scratched out on a spare roll of parchment.

This was the magic of a people living among the same trees at the end of the same muddy lane for hundreds and hundreds of years. They knew that demons haunted the cemetery, that angels guarded their borders, that their sages could intervene for them with God Himself and make miracles to solve the problems of their day-to-day lives. It was an entire enchanted ethos, a magic stitched into their experience moment by moment.

And it’s gone now; it was a combination of place and time and people, a delicate ecosystem of superstition and socialization, and even if it could be resuscitated on these shores, it would, of necessity, be different. The demons who haunt forests and shtetls are surely not the same as those who lurk on fire escapes and at the back of service alleys.

No, we can no more bring back the dead magic of my ancestors than we can unburn an intricate wooden synagogue.

But we can build replicas.

The blueprints are already there. Yiddish literature is full of fantastical stories: the holy sages working miracles, the nefarious demons plotting for their own gain. Though many of these Yiddish masterworks have been translated into English, and are at least theoretically accessible—check out the work of I.L. Peretz, S. An-sky, Der Nister—often, the tales are so submerged in Jewish context that they’re difficult for fantasy fans without a strong Jewish education to enjoy.

A few of us have begun to try to change this, though, writing fantasies as accessible to non-Jewish readers as they might be to members of our own community. In Spinning Silver, Naomi Novik gracefully transmuted the familiar tale of Rumpelstiltskin into a medieval Jewish context. Adam Gidwitz sent three exceptional 13th century kids on a quest to save a copy of the Talmud in The Inquisitor’s Tale, and now, I hope to make my own contribution to the small but mighty subgenre of Jewish fantasy.

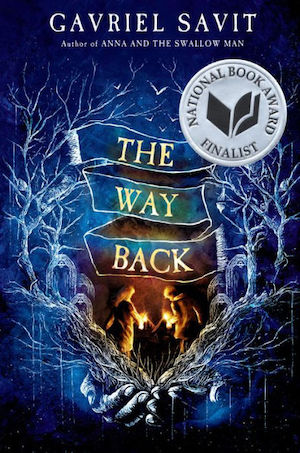

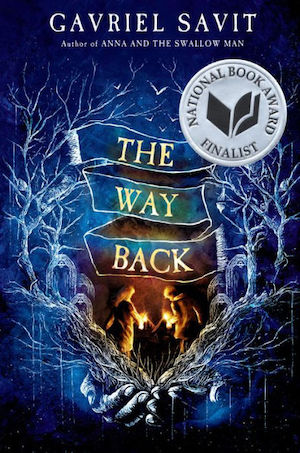

Buy the Book

The Way Back

My new book, The Way Back is the story of two kids, Bluma and Yehuda Leib, from the little Jewish village of Tupik in Eastern Europe: how they each encounter the Angel of Death; how this encounter sends them spinning off through the realm of the dead known as the Far Country; how, by bargaining with ancient demons and beseeching saintly sages, they finally make their way to the very doorstep of Death’s House. One of the main reasons I wrote it was to try and recapture the lost magic that the man at the end of my grandfather’s photo album must’ve known.

It’s a spooky adventure of magic and mysticism, but beyond the fun of traveling alongside Bluma and Yehuda Leib, of meeting and—sometimes—evading the demons, I think The Way Back has something else to offer.

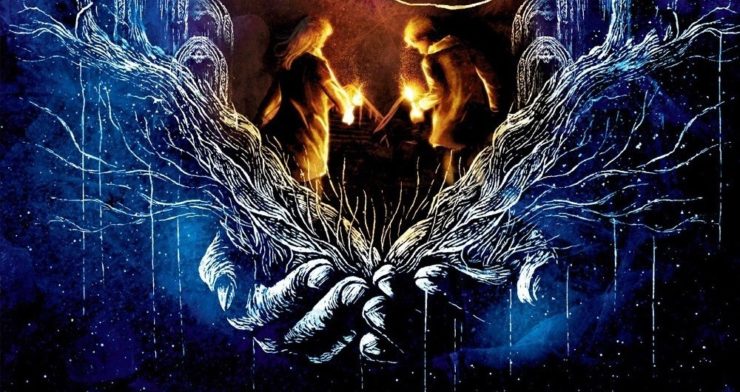

In the book, one of the ways you make your way into the Far Country is through the cemetery: a long and winding path that meanders among the gravestones. Maybe the book itself is such a path— back through the death and destruction of the 20th century, back and back to my ancestors’ own worn kitchen table, where the world is a little darker, a little colder, and a lot more enchanted.

Here the demons lurk just beyond the bounds of the bright firelight; here the dead magic is still breathing and warm.

Come on back.

Gavriel Savit holds a BFA in musical theater from the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor, where he grew up. As an actor and singer, Gavriel has performed on three continents, from New York to Brussels to Tokyo. He is also the author of Anna and the Swallow Man, which the New York Times called “a splendid debut.” Learn more about Gavriel at his website.