Steampunk is rooted in the maker philosophy. It rejects mass production and the smooth, factory-fresh minimalism of futurist design and instead embraces the one-of-a-kind, the handmade, the maximalist. And if you’ve ever watched a Studio Ghibli film—especially those helmed by Hayao Miyazaki—you know that this is the defining ethos of the studio. They’re famous for the level of craft that goes into their films; every cell is treated as an individual work of art, every detail is absolutely intentional, and every scene is bursting with the kind of intricate, lived-in realism that is anathema to budget-conscious animation productions. The studio is notorious (in both connotations of the word) for how hard its animators work to achieve the level of artistry that has set Ghibli apart from nearly every other big animation studio. Like a steampunk tinkerer, each of the studio’s animators is devoted to their craft to an obsessive degree.

With this philosophy tangibly present in every film, it’s no surprise that Studio Ghibli’s inaugural1 feature Laputa: Castle in the Sky is, per Jeff VanderMeer in The Steampunk Bible, “one of the first modern [s]teampunk classics.”

The term “steampunk” was actually coined by accident. Or at least that’s the case according to Mike Perchon in his literary study “Seminal Steampunk: Proper and True.” When K.W. Jeter used the term to describe his book Molok Night in 1987, it was simply to narrow the definition of his work from general science fiction down to the more specific Victorian-infused retro-futurism we have since recognized as the hallmark of the genre. According to Jeter himself, the “-punk” in steampunk was meant as a joke and was not really intended to denote the countercultural interests or political activism of punk. Yet, despite how entrenched the term has become as an aesthetic marker, I would argue the best steampunk stories regularly engage with social and political issues, with the rewriting of history through alternate histories and technologies operating as a deconstruction (and reconstruction) of contemporary concerns. And one of the greatest is Laputa: Castle in the Sky.

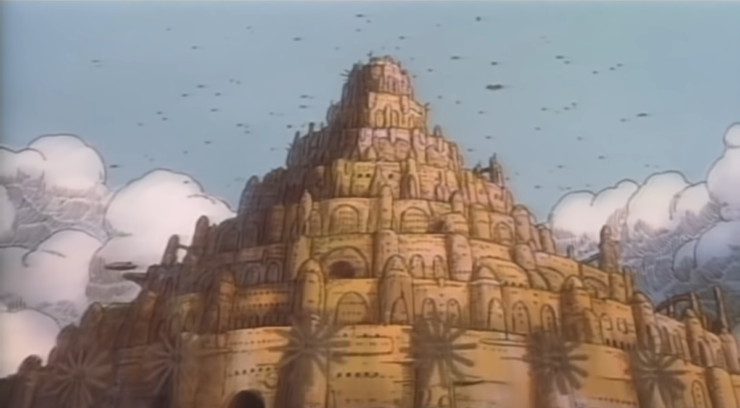

Released in 1986, Castle in the Sky (the slightly shorter title used for its US release) is set in a vaguely European, Edwardian milieu and has a fairly simple plot. A young girl named Sheeta is in possession of a stone necklace imbued with peculiar powers. Both the military, led by the skeevy secret agent Muska, and a ragtag family of airship pirates want to get their hands on Sheeta’s amulet, which is the key to finding the floating city of Laputa. While making an accidental escape from her pursuers, Sheeta falls—or rather, floats—down from an airship mid-flight and is caught by an industrious and optimistic orphan boy named Pazu. Sheeta and Pazu become friends and the two of them go on the run, but it isn’t long before they are caught and separated. There are more scuffles, various escapes and escapades, and a truly horrifying sequence of destruction before the two are reunited and finally find their way to Laputa, where Sheeta’s necklace originated. There, Sheeta must face the legacy of Laputa, which is intrinsically tied to her own.

The film is full of steampunk iconography, including airships, retro-futuristic robots, and steam-powered mining equipment; the opening scene of the film features an airship battle that could grace the cover of any steampunk anthology. But Miyazaki is never just about aesthetics without meaning; every piece of machinery reflects those who operate it. Dola’s pirate crew—scrappy and tough but also a warm and loving family—pilot their small, utilitarian ship with their laundry flying from lines strewn across the decks. Meanwhile, the military’s oppressive power is brought to visual life in the smooth, gravity-defying solidity of their enormous flying tank, The Goliath. Even the aging, complicated steam-powered mining equipment used in Pazu’s town offers insight into the state of the people that live and work on (and under) the ground. This refraction of people as seen through their ships and other tech is both a crucial piece of characterization that introduces us to these central players within the first few moments of the film, and a subtle commentary on the overarching themes of personal responsibility for the uses—and abuses—of technology throughout. This connection between technology and its users become much more overt when we encounter Laputa and learn more about its history.

Laputa, named for the floating land in Gulliver’s Travels, is a legendary construction that resembles a castle or immense fortress, built in the distant past by engineers who had mastered the power of Ethereum, a mystical power source found deep in the Earth (and the material Sheeta’s necklace is made of). The mastery of Ethereum has become lost to time; it is posited by Pazu’s elderly friend Uncle Pom that the loss of the knowledge to control Ethereum is why Laputa and its technology has drifted into legend. During a confrontation with Muska, Sheeta explains that the inhabitants left the floating world because they realized that humans were meant to live on Earth, and that the technology/power that they drew from the Earth to create Laputa was meant to connect them to the world—both to the literal Earth and their fellow humans—not carry them above it. They knew that they had overreached and created something dangerous and out of sync with the rest of the world. Laputa itself is both beautiful and frightening in its depiction as a floating mass that defies the laws of nature, only to be slowly retaken by nature after its inhabitants are gone.

We’re all familiar with the famous Arthur C. Clarke quote that “any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic.” Ethereum is treated as both mystical—it’s a glowing rock that can make things fly—and technological. The stone powers machinery, all of which has the recognizable, tech-heavy design of the steampunk aesthetic. Yet there is more to it than just the ability to power machinery. In a small but gorgeous scene about halfway through the film, Sheeta and Pazu are underground with Uncle Pom and he talks to them about the Earth and the way Pom, as a lifelong miner, feels he is connected to it. He cracks open a stone, revealing an otherworldly glow inside the rock itself, which then takes over the entire cavern, igniting the same glow in Sheeta’s necklace and making the connection between the Earth and the power behind Laputa suddenly clear. Ethereum—magical or natural or both—is the key and whether the technology it powers is ultimately magical or scientific is an interesting distinction that is entirely irrelevant to Miyazaki’s treatment of it in the plot, though it is hard not to draw a parallel between Ethereum and the dangerous, radioactive elements we have put to various uses—both creative and destructive—in the 20th century and beyond. In this case, it’s enough that the machines powered by Ethereum are made by humans in the name of progress, to serve human ends for both good and evil.

Laputa is an invaluable find for every primary (and secondary) character in Castle in the Sky. For Sheeta, it’s a legacy and a link to her own unknown past. For Pazu, it’s an obsession he inherited from his father and an escapist fantasy from a life that is full of hard labor and scarcity. For Dola, the air pirate captain, it’s the ultimate treasure score. And for Muska, it’s immeasurable power and world domination. That this technological marvel is so many things to so many people is the key to understanding the ambivalence Miyazaki brings to his explorations of technology and industrialization. As a Japanese creator who was born during World War II, Miyazaki knows better than most the destructive power of technology in the hands of the powerful, and he also deeply understands the seeming impossibility of separating industrialization and weaponization, or of making “progress” while preserving our natural resources. Technology always has the potential to destroy, and human nature rarely passes up the opportunity to turn its inventions and resources to their worst possible purposes.

While there are many elements I could highlight to illustrate Miyazaki’s complex take on technology as both advancement and horror, one of the most distinctive in the film are the robots that guard the now uninhabited Laputa. Fusing retro-futuristic and organic design, they have a sort of vacant kindness woven into their appearance—their lopsided eyes are very similar to the adorable kodama in Princess Mononoke—that belies their capacity for death and destruction. They are protectors of Laputa that help Sheeta on more than one occasion, but the level of power they are capable of is staggering. Like Lady Eboshi’s Iron Town in Mononoke, there is no absolute moral line drawn between the benefits and the terrible price of “progress” in Castle in the Sky. What is beautiful and magical is also dangerous and destructive. The technology that powers Laputa could transform the hardscrabble, working class lives of the miners in Pazu’s town, making their jobs easier and more fruitful. It can also wreak absolute and deadly havoc, a horrible truth made explicit in a genuinely terrifying sequence about halfway through the film, when one of Laputa’s fallen robots comes back to life and utterly destroys a military outpost.

Laputa is not the only film that exhibits Miyazaki’s use of steampunk as both storytelling tool and aesthetic. Howl’s titular castle certainly has the look of a tinkerer’s elaborate construction, and the war at the center of the film is fought with airships and other deadly technological marvels. Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind hinges on the dangers of human ambition and incorporates the hybrid mechanical-organic designs that are Miyazaki trademarks in later films. Even Spirited Away has certain retro elements in the spirit world that defy the film’s 21st century setting. It’s fairly common for critics and fans to comment on Miyazaki (and by extension, Studio Ghibli’s) common themes: anti-war sentiment, environmentalism, the wide-open potential of the young protagonists. Throughout all of his films, Miyazaki is concerned with the ways people are connected—or rather, disconnected—to the natural world and how this disconnection is often the result of our increased reliance on industrialization and technology.

Of all of his films, it is probably the trio of Nausicaä, Princess Mononoke, and Castle in the Sky that are the most direct in tackling the ambivalence of technological progress through the lens of SFF. And of these three, Castle in the Sky is the most clearly centered on the repercussions of the technology itself, rather than employing industrialization as part of a larger story. Sheeta and Pazu are the beating heart of the film, but their adventures are less about their individual desires than how they have become entangled in something much larger than themselves. It is really the pursuit of Laputa—the pursuit of power, of wealth, of answers—that defines the story and encourages the audience to consider the price of technological advancement.

Buy the Book

A Psalm for the Wild-Built

Sheeta, at the end of the film, must make a hard and terrible choice. Laputa is her home by inheritance, and it is a beautiful and wondrous place when seen through her and Pazu’s eyes. But Laputa is also a weapon whose potential for destruction is near-limitless—and Muska’s desire to possess it is similarly boundless. Muska is a specific kind of villain that is common in steampunk. He is both personally ambitious and representative of a military-industrial complex that will seek power at any cost. From his dark, round sunglasses to his impeccable suit and cravat, he is the Edwardian villain-dandy extraordinaire (and a very common steampunk character design trope). To save the world from men like Muska, Sheeta must destroy Laputa. Where this choice between industrialization (that could potentially improve the lives of ordinary people) and the preservation of the natural world was much more difficult to parse in absolute terms of “right” and “wrong” in Mononoke, this bittersweet resolution is much more straightforward in Castle—though no less sad or complicated for the heroine that must make such an immense decision.

Despite the eurocentric (or even London-centric) nature of many steampunk portrayals in books and film, Japan has a long history of steampunk storytelling that can be traced back as early as the 1940s. I find it a fascinating coincidence that Castle in the Sky was released just a year before the actual term “steampunk” was coined; the film followed in the footsteps of a long tradition and helped define the genre before it even had the name we recognize today.

Are there substantial differences in the way an Asian creator approaches the tools and iconography of steampunk? I think the answer is yes, but as the genre itself has been pretty consistently rooted in European Victoriana—and was ultimately named by an American—it can be difficult to put my finger on definitive differences. In later Japanese steampunk works like Casshern (2004) and Steamboy (2009), the conventional, euro-inflected visual and political language of the genre is even more at play than in anything by Miyazaki. Perhaps the differences come down to philosophy rather than visuals or cultural cues. Because Japanese steampunk can trace its roots to the post-WWII years and the last gasp of a mighty empire (and the rise of monstrous technologies in the atomic age), there is a certain ambivalence to technological advancement deeply present, even through the lens of alternative history. Western steampunk stories are often set at the height of the colonial and industrial power of Europe (especially Great Britain), while Japanese entries in the genre2 are perpetually aware of the collapse of their imperial might on the world stage and the destructive height of industrialization. Does eurocentric steampunk revisit the past as a form of nostalgia for the glorious memory of empire? It would seem that the collapse or decline of that past power is something Japan has accepted in a way many Western nations have not. It’s harder to speak for Asian and/or Japanese creators in general, but I don’t think anyone could accuse Miyazaki of imperial nostalgia, no matter how fun and whimsical his films are. Looking back at (imaginary) technologies past seems to provide a certain amount of distance for the film to look at harder truths in the real world, not to soften them, but to divorce them from the complex politics that muddy the discussion. At this point, I’m raising more questions rather than bringing this to a close, but I think it’s something worth thinking about if you accept the premise that stories like this are placed in a steampunk context for socio-political reasons rather than the purely superficial.

For some, steampunk will always be shorthand for a particular aesthetic. But what Miyazaki does in Castle in the Sky demonstrates why the “-punk” in steampunk can be a genuine call for radical approaches to SFF storytelling. K.W. Jeter may have been joking around when he created the term, but Miyazaki’s steampunk masterpiece shows the power of interrogating technology through the lens of fantasy, where we can extract ourselves from our immersion in an increasingly tech-centered world to look at these marvels from a distance, to see both their wonder and their potential for ruin.

Amber Troska is a writer, copyeditor, and steampunk witch from a shadowy holler below the Mason-Dixon. When she’s not hexing assholes and adding unnecessary cogs to her top hat, you can find her shouting about books and all things SFF on Twitter @atroskity.

[1]Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind was made and released earlier, though not technically created under the Studio Ghibli umbrella.

[2]There’s an argument to be made for steampunk as a storytelling mode rather than a distinct genre or subgenre, but for the sake of time and word count, I won’t be making it here.