The more I think on where to start talking about the idea of queering SFF, which is something in between a reclamation and a recognition process, the more I realize there’s no concrete place to begin. To be queer is to be strange, fantastic and outside the normative box. Considering how easily those words apply to speculative fiction, it’s not surprising that some writers of SFF have engaged in a great deal of play with the concepts of gender, identity and sexuality. But how far back could we say the tradition of speculative fiction goes? If we answer “for as long as people have been telling stories,” then when did they start telling stories that questioned the social designations of gender and sexuality? I can’t pick a text to point to and say “yes, this! This is where it started!”

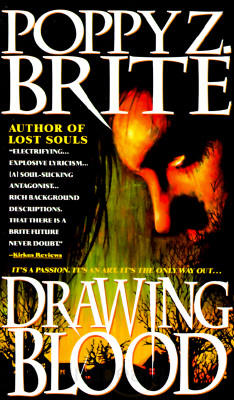

Instead, the best place to begin might be with individual experience. Everyone has a different story about the first book they read with a queer character who wasn’t just the villain or the guy who died in the first chapter. It was mind-blowing and unbelievably freeing to hold a real, published book in my hands and realize that the main characters weren’t straight. I have two examples for my starter books, both read when I was around thirteen: The Picture of Dorian Gray by Oscar Wilde and, on a totally different end of the spectrum, Drawing Blood by Poppy Z. Brite.

There’s a big academic tangle over The Picture of Dorian Gray (is it gay? Is it spec-fic?) that I’m going to avoid entirely. When I read it for the first time, I thought that Basil was in love with Dorian and Dorian had a thing going on with Henry. Nowadays, I could argue ‘til the world ends about whether it’s just homoerotic or actually gay, but that first read was pretty eye-opening. Not only was this a real, published book, it was a classic about “the love that dare not speak its name.”

Wilde’s only novel is occasionally too verbose (there’s a shorter original version which is also much more blatant in its eroticism), but the moments of high dramatic tension in it will still steal a reader’s breath. When Dorian shows Basil his aged portrait, wrecked by vice, it’s hard not to shiver. Basil’s murder at the hands of the man he loved drives home the intensity of Dorian’s fall from grace. The emotional connections between the characters are the strongest part of the story, though; Basil’s hopeless devotion to Dorian is heart-wrenching, doubly so when the reader considers how impossible that love was in their time.

The influence The Picture of Dorian Gray has had on generations of readers who’ve gone on to make movies, music and new stories based on the tale is undeniable. The book’s main narrative concern is not actually romance, but the subtext is rich with implications that make it a worthwhile read for anyone considering the history of queer characters in speculative fiction. I recommend it to anyone who hasn’t read it before: it’s just one of those books that everyone should try at least once.

On the flip side, Poppy Z. Brite’s Drawing Blood is clear as glass: it’s spec-fic, it’s gay, and it’s not shy about it. The world of Drawing Blood is constructed to hook it into a cultural continuum. There are references to Neuromancer, Naked Lunch, R. Crumb and Charlie Parker—all of which firmly place the book in with the things it calls to mind. It’s a legitimizing affair almost as much as it is a way to make the reader identify with the characters. By placing the narrative in a recognizable space, Brite asserts the book’s right to exist in that same spectrum. I would hardly call it a perfect book, as there are some passages of awkward writing that one can generally expect in an early novel, but I’ve still read it more times than I can count throughout my life. Part of this is that the references mentioned above really did resonate with me and still do (I don’t think I’ll ever grow out of cyberpunk). Much more, though, it’s how enthralled I was the first time I read the book. That feeling of pleasure hasn’t ever worn away completely.

Trevor’s side of the plot, a haunted-house story, is intense in a creative and under-stated way for the majority of the book before it erupts into the madness of the ending. Zach’s hacker yarn is just as much fun for the kind of reader who really, really liked the movement in the days it seemed like a viable and fascinating future. I’m not sure how that will have aged for new readers from the millennium generation, to be honest, but anyone who was growing up in the ‘90s will appreciate it. The way their lives collide and combine is somewhere between romantic and crazy.

There actually isn’t much sex in Drawing Blood in comparison to later books like Exquisite Corpse, and where it does play a part it builds the romantic narrative between Zach and Trevor. The scenes are fairly explicit which was in and of itself a new experience for the younger me. I had the internet, so it wasn’t like I was unaware of things like slash fandom, but to read an actual sex scene between two men in a book was sort of a “level up” experience from The Picture of Dorian Gray. Men weren’t just allowed to love each other in books: they could act on it, too. The scenes have a kind of strange, rough tenderness that is common to Brite’s work and that makes them seem real. The physical attraction between Zach and Trevor is treated as natural and erotic. That is what I always hope for from queer romance in spec-fic and Brite manages it well. I’m not sure if I would necessarily recommend Drawing Blood—the nostalgia factor makes it hard for me to weigh the book’s actual relevance—but I still like it. At the very least it can be a guilty pleasure. (Brite’s later books, which are commercial fiction about the New Orleans kitchen scene, have better writing and stronger characters. They’re a very different sort of animal from the horror novels, though.)

There are so many more books to consider, but for now, that seems like a good start. I know that both of these books dealt with gay men, but I didn’t run into much good lesbian SFF until later. It’s always seemed harder to find. I’m not sure if that’s my bad luck or not, but I’d like to find more books with queer female or female-performing leads. Or, even more under-represented, intersex characters. So far the only place I have encountered any has been Elizabeth Bear’s “Promethean Age” series.

To conclude: those were my first experiences, but what were yours? Suggest however many books you like. I could always use more to read.

Lee Mandelo is a multi-fandom geek with a special love for comics and queer literature. She can be found on Twitter and Livejournal.