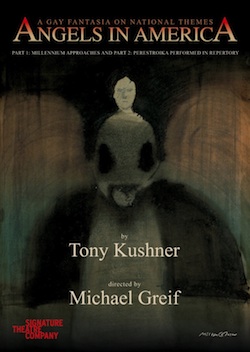

Generally in this series, the books I’ve looked at have come firmly out of the speculative tradition, and have been prose fiction—no dramas, only a few books that are figured more as queer lit than as spec-fic. I think it’s high time to remedy that with a contemporary classic of gay literature that’s also pretty damned speculative—what with the angels and the exploration of heaven with God gone missing—in the form of Tony Kushner’s Pulitzer-prize winning play-in-two-parts, Angels in America: A Gay Fantasia on National Themes.

This is not a piece that’s going to come up on the average reader of queer SF’s radar, because it isn’t figured as SF, and it isn’t a novel. That’s a shame, because Kushner’s play (also adapted to a miniseries by HBO) is eminently readable, emotionally gripping, and thematically charged; plus, it’s flat-out speculative, no question about that. As a contemporary story, it also does what much SF does not: engages with the AIDS epidemic, the politics of the Reagan era, homophobia, religion, and racism.

A common critique of queer speculative fiction based out of the SF community is that it fails to engage with the realities of being queer and with contemporary LGBTQI experience—issues of homophobia, of systematic discrimination, of watching a generation of friends and loved ones decimated by disease. While there is certainly room for positive queer futures—I love books where gender and sexuality are both diverse and unremarkable—there is also a need for fiction that deals with the things that queer people actually have dealt with, especially the ugly stuff that shapes each and every one of us in contemporary culture. (I am too young to remember the AIDS epidemic; but I am not too young to have friends who survived it, and not too young to have friends who are positive and living with HIV.) This is the thing that speculative fiction that comes out of the queer community tends to do and encompass, all the time, and that is extremely valuable in a discussion of queerness in SF.

So, today we have Angels in America by Tony Kushner, a drama that blew me away when I first read it and left me with a lingering, complex set of feelings about what it had to say. It’s only a long night’s reading—despite the size of the text, it’s a fast read thanks to the format—and I cannot recommend picking it up enough. I also can’t possibly encompass all of what Kushner is doing in this short appreciation, but I’m going to give it a shot.

Angels in America engages with the struggles of the “age of AIDS” through humor, the fantastic, and the down-and-dirty world of interpersonal connections and failures to connect. As a text it provides an intimate sense of many of the struggles associated with the 1980s for the American gay community (which are covered from a historiographic viewpoint in texts like Neil Miller’s Out of the Past, for those who are curious). The realities of this era are so viscerally awful that it’s difficult to manage them all in one two-part drama, but Kushner does so astoundingly well: the contradictions of conservative politics, the class warfare that resulted in death for thousands of gay men who could not afford prohibitively expensive early medications, and on a personal level, the impossibilities of caring for a dying partner, for dying friends, and for yourself, emotionally and physically. That Angels in America features a primary relationship that, ultimately, fails for fear of death—that’s intense.

Actually, intense is the perfect word for this play. The emotional content, the social critiques, the fantastic—all of these are turned up to eleven. Angels in America is unapologetic, uncomfortable, and infinitely rewarding. The cast is large (and played by a small set of actors, which is fascinating in a performance), and the majority aren’t entirely sympathetic: Louis cheats on his sick lover with Joe and is quite frankly a well-meaning racist; Belize is cruel to people who may or may not deserve it; Joe cheats on his wife and beats Louis after being confronted with his boss Roy Cohn’s sexuality. Only Prior is for the most part a sympathetic character, and he’s the protagonist, so it’s not entirely surprising. He’s also the one who’s having visions of angels and an empty heaven and bonding with Harper. Joe’s wife Harper is also a heart-breaker and a highly empathetic, rich character, as well as one of the only women in the play (which does, after all, take place in a male-centric community).

Furthermore, some of the folks involved in this story are downright horrific, such as Roy Cohn, the conservative lawyer and power broker who has such eviscerating, wince-inducing speeches as this one, to his doctor, while he’s saying that he can’t have AIDS and that it must be said that he has liver cancer instead:

“I don’t want you to be impressed. I want you to understand. This is not sophistry. And this is not hypocrisy. This is reality. I have sex with men. But unlike nearly every other man of whom this is true, I bring the guy I’m screwing to the White House and President Regan smiles at us and shakes his hand. Because what I am is defined entirely by who I am. Roy Cohn is not a homosexual. Roy Cohn is a heterosexual man, Henry, who fucks around with guys.” (52)

To be honest, I would like to quote the entire scene with his doctor for its hair-raising nastiness, because it’s not exactly a fantasy. Roy Cohn was a real person, and while the things attributed to him in this play are conjecture, he was not a unique figure in conservative politics of the ’80s. It’s also telling that in the story it’s Roy Cohn who gets the AZT, not our protagonist, Prior (until, of course, Belize has Louis snag some when Roy dies). Roy only gets it through his blackmails, his connections, and his money. The distribution of drugs was a special type of class warfare—the poor, even the middle class, were for the majority going to die for lack of care. Kushner brings that home with crystal-clear consequences.

Wild humor and over-the-top strangeness are used throughout to counterpoint the eviscerating sorrow of the truth, and the fear of death. The speculative elements are fundamentally necessary to the plot and the effect of this story, while camp and comedy are the only weapons available to combat terror, loneliness and despair. Kushner is well aware of this and uses it to full effect, bouncing between extremely emotional scenes and outright hilarity. His author-notes are all rather specific on how to get those laughs, and it’s not by playing with silliness—it’s by playing with seriousness. (141-143) Tragedy and comedy are two sides of one coin.

One of the memorable lines near the ending is with Prior in heaven, discussing matters with the Angel. He says, of the missing God: “And if He returns, take Him to Court. He walked out on us. He ought to pay.” And then Roy in hell is going to be God’s lawyer, in one short aside scene. Comedy gold, layered over a very serious emotional realization regarding faith, religion, and the nature of God. The blessings of the Angel include, at one point, a fabulous orgasm—you’d just have to read it to get the significance of sexuality as life-giving despite its new dangers, and the comedy Kushner employs to make that obvious.

Angels in America is a drama that I’m likely to come back to again and again for its rich, wonderful prose and the amazingly varied cast of characters—and the manic, strange, inextricably fantastical nature of the whole story, which is as much about religion, mystery, myth and faith as it is the realities of gay life in the ’80s. The scenes with the Angel and in the abandoned Heaven, and the culmination in Prior’s asking for the blessing of More Life, are high speculative drama. Any fan of fantasy is likely to be ensnared by them.

But in the end of this appreciation I’ll leave you with a bit of Prior’s final speech, which lifts the terror, pain and suffering in the book to a different place, rhetorically:

“We won’t die secret deaths anymore. The world only spins forward. We will be citizens. The time has come.

Bye now.

You are fabulous creatures, each and every one.

And I bless you: More Life.

The Great Work Begins.”

Lee Mandelo is a writer, critic and occasional editor whose primary fields of interest are speculative fiction and queer literature, especially when the two coincide. Also, comics. She can be found on Twitter or her website.