Next up on the docket for this month’s Extravaganza, following Nicola Griffith’s historical novel Hild, is a totally different kind of book: No Straight Lines, an anthology of “four decades of queer comics,” published by Fantagraphics Books in 2012. The book opens with a brief history of the development of LGBTQ comics and then progresses through around 300 pages of excerpts and shorts, arranged by time period, that give a broad and engaging glimpse of the field as a whole.

As for its place here: there’s a fascinating overlap between comics and speculative fiction that goes back to the pulps—and that’s also true of queer comics, which often straddle a fine line between genres and audiences. The comic as an outsider artform, as a “genre” work, often stands alongside other, similar types of stories, like the ol’ science fiction and fantasy yarns we tend to enjoy. And, of course, some comics are themselves actually pieces of speculative fiction—superheroes, aliens, superhero aliens, and things like “transformation into other forms” are all pretty common tropes.

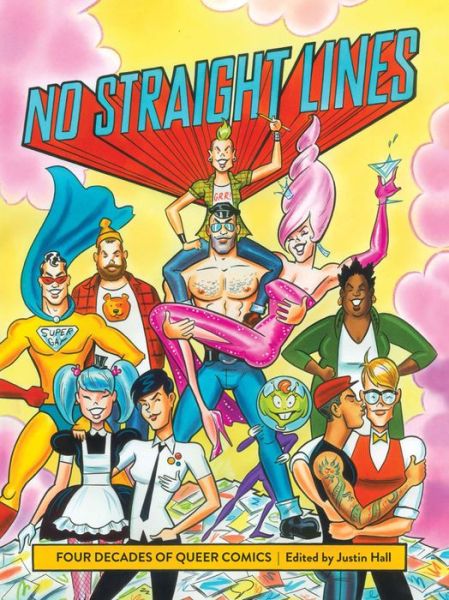

No Straight Lines contains a balance of types of stories, ranging as widely as it does through the publishing history of queer comics. Sometimes there are genies who grant wishes; more often, there are personal narratives and slice-of-life stories. The vibrant, playful cover for the book reflects that variety: it’s got dykes and superheroes and bears, queens and punks and then some, all standing gleeful and proud atop a pile of comic books. And since all of the pieces collected here are graphic stories of some sort or another, the book as a whole does seem to me to be the sort of thing an audience inclined to sf and/or comics might appreciate.

I sure did, at least.

Of particular interest to me were the shifts in tone and style that become remarkably clear between decades when these pieces are all grouped together: the ripe and blatant sexuality of the early “underground comix”-inspired zines, the anger and political consciousness evolving during the AIDS epidemic—the plague years—and also the growing presence of the “B” and “T” from the acronym in contemporary comics. The generational differences are also bracketed by clear differences in life experience between gay and lesbian comics, as well the shared but also quite variable experiences of being queer that are shaped by gender, race, and socioeconomic status. Hall has managed to collect a nice smorgasbord of stories, here, and more than just in terms of genre.

That’s the thing that I think will appeal most for this book—the reason I think it’s worth picking up if you have any interest in (a) queer stuff (b) comics and/or (c) sf. There’s just such variety. Though, as Hall recognizes, even the sampler he offers here is in no way representative of the real depth and breadth of the field. Limited as his selections are to shorts and easily excerpted chapters or sections, there’s plenty that’s missing, though that’s also addressed in the “recommended reading” with further anthologies and graphic novels at the end. But I appreciated, in reading this anthology, the sense that I got of how much was really out there, and how much has been out there since before I was even born. There is a genealogy of LGBTQ stories in graphic form, one that spans erotic and mundane, playful and serious, comic and tragic, realist and speculative—and Hall has given, in No Straight Lines, a delightful cross-section of that genealogy.

As for particular pieces I found enjoyable, they also ranged across all of those sorts of charting factors. “My Deadly Darling Dyke” by Lee Marrs was an exceptionally silly gothic parody that had me giggling with its over-the-top camp; “The Tortoise and the Scorpion” by Carl Vaughn Frick, on the other hand, is a visually quite strange story about the conflicts of the AIDS outbreak for gay men—using anthropomorphized animals to tell the story, until they eventually cast off their shells and contortions to become regular men again together.

Then there are pieces like the one-page selection from 7 Miles a Second by David Wojnarrowicz, James Romberger, and Marguerite Van Cook—a handsome color illustration of a person gone giant-size, smashing what appears to be a church-building, paired with a long text section on the rage and helplessness of those “plague years.” It’s moving and deliberate, as well as beautiful. And then—because there’s always more, it seems like, in this book—there are selections from Hothead Paisan: Homicidal Lesbian Terrorist by Dianna DiMassa, which is so absurd and extreme as to be an excellent cathartic experience. (I’m also going to say Hothead is speculative in the total extremity of the comic itself, even if there aren’t any dragons or giant squids involved.)

I also enjoyed selections from Alison Bechdel and Jennifer Camper, Eric Orner and Gina Kamentsky and others whose stories are “realist”—slice of life queer narratives, dealing with the experiences of social, personal, and political difference—and compelling as all hell. These stories fit well together in their uniqueness and verve; even the ones throughout the collection that I found off-putting or “unrelatable” or totally alien to my experiences are fascinating for the views they offer into what it was like to be someone else, somewhen else, and to be queer there in some stripe.

Really, I’m glad this anthology is out there, and I think it’s a great read, not just for the stories alone but for what they represent together: a history, a genealogy, or LGBTQ writers and artists telling stories that reflect their experiences and knowledge of the world. It’s good to see, and it’s good to have out there to show that we’ve always been around, drawing and writing and adapting genre mediums to queer purposes—genre mediums that are, maybe, more open to us to begin with. If I wanted to get philosophical, it’s one of the things I find welcoming about straight-up prose sf too, and comics certainly share the tendency.

So, we’re there in historical novels like Hild and we’re so very there in comics like the ones collected in No Straight Lines—where else, and when else? There’s more to come, of course.

Lee Mandelo is a writer, critic, and editor whose primary fields of interest are speculative fiction and queer literature, especially when the two coincide. She can be found on Twitter or her website.