Words have power. In the hands of storytellers, words can paint tapestries on your brain, let you inhabit someone else’s skin, and take you to a strange and distant universe. The particular choices a writer makes—this word over that, this nickname instead of the other—are the backbone of the narrative. The tone of a story relies entirely on word choices and phrasing: is it humorous, darkly witty, serious or horrific? How does the narrator feel about this other character? A talented writer won’t have to tell you—you’ll simply know, deep down, because the words held all the information you needed.

This is no less true of queer fiction, speculative or otherwise. The danger, or perhaps difficulty, is that when writing about a people who are marginalized, abused and degraded through language on a daily basis in our own culture, the power of words seems to triple. When the language of power devotes itself to hurting the people you are writing or reading about (and this also, obviously, applies to talking about people of color and other marginalized groups), overtly or covertly, using that language becomes a minefield.

How can an author capture those nuances effectively in their fiction, avoid the pitfalls and wrestle with the question of authenticity—especially when authentic language and dialogue involves slurs and hate-speech? There is also the question of how a queer character uses language as a part of their performance and identity—because there are nuances there, too, ironic self-reflection and gender verbiage that might not be directly obvious. Writers on the LGBT spectrum who are writing characters that identify differently from themselves also have to consider these differences in language.

The word “queer,” for example—it is both a word of hurt and a word of reclaimed power, depending on usage. That’s a thing I learned young: when somebody calls you a queer, say “yeah, and?” It removes their power, their attempt to hurt—which isn’t to say it didn’t still leave a mark; just that you refuse to let that person see it. I’ve claimed the word as a part of my identity.

A male character, however, might identify himself as “gay” and not “queer.” Contemporary language is hugely fond of labels and most people choose to use those labels for ease of communication and ease of grouping. I will admit, “queer” often confuses people who would really like to know which end of the spectrum I’m on—am I a lesbian, a bisexual, am I trans or cisgendered? Many folks will actually ask you if they don’t feel your label is accurate or revealing enough. That’s a topic for another time—intrusiveness and the “right to know” that are supported in Western culture towards queer folks—but it’s something to consider when writing a character who falls outside the normative gender roles. Despite a desire not to label, most of us are forced to at some point or another, because “I refuse to identify myself, gender or otherwise” frequently leads to badgering or outright laughter, and not just from the straight community. Pick a label, stick it on, stay in line—that’s a fairly universal problem. (There will be another, more in-depth post on identity and gender performances in the future. For now, we’ll just touch on the language issues.)

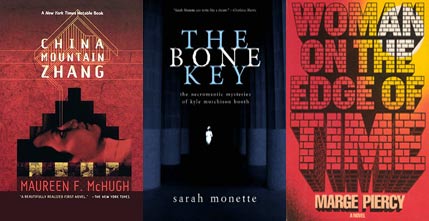

Aside from the words the character may or may not use to identify themselves (as discussed in this series before, characters who do not identify such as Booth from Sarah Monette’s The Bone Key are equally important to consider), there is also the way they talk about the world around them. One of the best short examples I can think of for this is from Caitlin Kiernan’s The Red Tree. The main character is a lesbian, female performing and identified, and when she is discussing another woman character in sexual terms she uses the phrase “clit-tease.”

That seems like a very small detail; it’s only a one-word difference from the more usual “cock-tease.” The use of it, on the other hand, tells a reader a great deal about the narrator. Another lesbian character, more masculine identified, might have still used the phrase “cock-tease”—or might not have. The use of that single word denotes a great deal about how the character sees herself, her sexuality, and her performance.

Knowing the character you want to write goes a long way into this process. Just because she is a lesbian does not mean she performs in any specific way: she could be a masculine-performing woman or she could be a feminine-performing woman, or she could be genderqueer and playing with those roles entirely, mixing and matching the social structures as she pleases. Furthermore, she could be a pre-transition woman who is still in the process of claiming a body that matches her gender (or, choosing not to). It is a responsibility for the writer to know not only these things about their characters but to put them into words without having to tell the reader flat-out. It’s all in the word-choice, the descriptions; especially first person point of view.

This brings us to the uglier part of the discussion: the reality for queer folks throughout history has been pretty unpleasant, to put it lightly. On the one hand, if you’re writing far future science fiction, you can play with that and dispense with gender roles and problems in your future, ala Marge Piercy’s Woman on the Edge of Time. (The catch being that you should have a good explanation.) However, if you’re writing contemporary, historical or even historically-inspired fiction, you need to acknowledge the reality of the times for your characters. Erasing pain, struggle and hate by pretending it never happened is disingenuous and never, ever a good idea.

So, if you’re writing queer characters you need to have an awareness in the text of the social climate, even if the story is not “about” homophobia or transphobia or their attendant violence. Maureen F. McHugh’s China Mountain Zhang explores issues of homophobia, danger and sexuality for a “bent” man in both a socialist America and in the China of that setting. In one, his sexuality isn’t tolerated (he could be fired from his job if anyone found out, for example), in the other it is punishable by hard labor or death. However, that isn’t what the book is “about.” It’s about Zhang as a human being, not as a Gay Man. He has a full personality with so many problems to juggle, each given weight. McHugh explores the delicate balance of all parts of his personality—as someone who passes for American-Born Chinese but has Latino roots, as a gay man, as a feckless youth developing into a creative adult—with love and attention. That is what makes the book tick; she doesn’t pull her punches about the ugly parts of the world but also never turns it into a melodrama. Zhang is an amazing character, framed by the narratives of other amazing characters who happen to be straight and are also dealing with the same issues of sexuality, money, freedom and safety. Obviously, their problems are different and Zhang has the most negative social pressure behind his self-expression, but McHugh masterfully handles the issues of language, sexuality, and identity. For a primer on doing this sort of thing well, refer to China Mountain Zhang.

As for contemporary settings like urban fantasies, though, odds are that if your character leaves their house at some point, they are going to get one dirty look or muttered phrase, maybe more. There are also the curious double-takes, the kids asking their parents if you’re a man or a woman (especially heartbreaking for some folks, though if your character is genderqueer this may rub them as positive—another thing to consider), people flat out asking you if you’re “a fag,” “a dyke,” etcetera. The locale of your story is important here, too—say your character lives in, oh, rural Kentucky versus a more metropolitan area. Speaking from experience, the Kentucky character is going to catch shit when they’re out in public. It is going to happen, with varying levels of aggression depending on gender and performance, especially if they’re alone in a crowd.

The writer then comes to a scene of homophobia, short or pronounced. Is it all right to use the language of negative power? It is accurate, but it’s also hurtful. There’s the danger that the reader might interpret the writer as having those feelings themselves. If the narrator is the one doing the hateful thing, that’s an even bigger danger. Some readers will conflate writer and narrator; it can be easy to do, even when it’s wrong. Avoiding that is a matter of building the story beforehand to show positive elements that outweigh your narrator, yet avoid preaching to the reader through the mouths of a secondary character. While it’s good to know that the writer doesn’t agree with their narrator and that the reader isn’t supposed to, either, it’s not so good when a secondary character begins explaining, usually in an “As You Know, Bob” fashion, why This Is Wrong.

In the case of a short, one-sentence instance and a queer narrator, how they react can be telling as well. Does it roll right off, do they engage, do they fume and stew about it, does it still hurt them even if they put on a brave face? Story is often about doing the worst things you can do to your characters, running them through the fire, and seeing how they come out on the other side. Their reaction to this kind of a situation can be revealing about their personality as a whole.

Though I feel like I shouldn’t need to say this, I’ll put it out there: none of this means you should exploit the potential suffering of a queer character just because they aren’t straight. This should not be the only aspect of their personality or even a big part of it. It is a part of their lives, yes, but it’s not the only part, much like their sexuality isn’t the only thing that makes them who they are. Ignoring the struggle is bad, capitalizing on it for melodrama is almost worse. I see a bit too much of that lurking around, usually secondary LGBT characters who exist in the story solely to be tormented and queer and sad. (They usually die by the end, too.) No, no, no. Just no.

I suspect the best thing to do is be truthful, avoid clumsy narrative, and don’t chicken out.

The fact is that negative power and negative language are a reality, and the suspension of a readers’ disbelief relies on the writer’s ability to present a familiar enough reality that they can get onboard. In second-world fantasy, the blow can and usually is softened for the reader by the introduction of socially apt terms for queer folk that fit the language of the characters. Sarah Monette’s Doctrine of Labyrinths series has its own words for discussing sexuality, as do many others, because sex is so social that each world will have a different way of looking at it. Different countries within the world, also.

My answer, in the end, is that it’s necessary to acknowledge that there is a language of dominance and that, in most worlds, it is directed against those it views as Other—such as queer people. To write a queer character means engaging with that reality, even if it’s just slightly, and to do otherwise is often a weakness in the development of the story. Which is also not to say that throwing around slurs and negative language is a good idea or will add realism—if it’s done badly or stupidly, it won’t, it will just be offensive.

Then again: imagine a world where there isn’t so much hate or hurt. Imagine a world with a different structure and find a new language of empowerment for that world. We have room for both in speculative fiction because we have the freedom to make up new universes wholesale when we need them. While I respect and appreciate the need for realism in contemporary settings, it’s also great to read a book where the queer characters aren’t at all Othered or persecuted, they simply are. It’s a world I’d dearly like to get to, someday.

What books, on your end, do you feel have handled issues of language, homophobia and identity well? What did they do right or what struck you about the story?

Lee Mandelo is a multi-fandom geek with a special love for comics and queer literature. She can be found on Twitter and Livejournal.