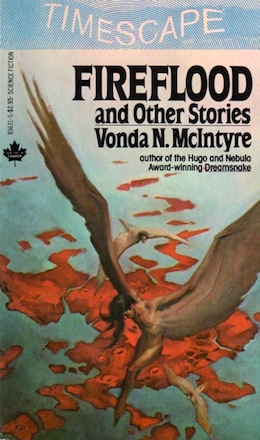

I initially picked up Vonda N. McIntyre’s 1979 collection Fireflood and Other Stories—the author’s first—because it included a novella featuring magical spaceship pilots, one of my favorite themes. I was surprised to find engagements with shifting gender and sex, polyamorous families, and thoughtful, emotionally resonant discussions of embodiment and shape change. In retrospect, this should not have been as surprising, because McIntyre’s Hugo- and Nebula-winning novel Dreamsnake was many readers’ first introduction to polyamory in fiction. (Samuel Delany’s Babel-17, which I previously covered, was another common entry point from the same era). Fireflood contains three novellas and a number of short stories, including the novella which was later expanded into Dreamsnake.

My favorite stories from Fireflood feature winged, flying humanoid beings, and are gently interlinked—even when explicit links are not provided, they suggest themselves. The collection starts with the eponymous Fireflood, a story of a human woman transformed into an armored mole-like creature for the purposes of a space colonization project that never happened. She escapes from the prison of her people to seek out allies among the graceful, elfin flyers, but nothing quite goes as planned. I really liked the interactions of characters who were transformed differently, and who are suffering differently under human colonial ambitions. The story avoids making one-to-one historical parallels, which has helped it age well—if not for some outdated disability terminology, it could have been written today. This holds true for most of the collection, too; it has a strikingly present-day approach, despite being almost forty years old.

“Wings” again returns to the theme of graceful, flying people—two of them left on a slowly abandoned and dying planet, both physically disabled. The keeper of a temple rescues a dying youth and sets the youth’s broken wing, and the two of them begin an uneasy relationship. The winged humanoids are born with ambiguous (“androgynous”) genitals, and must consciously choose their gender, which changes their sex accordingly. The keeper would like the youth to pick a specific gender, and the youth eventually makes that decision, but both of them have very different motivations. Another aspect that reads as very contemporary is that the youths, pre-decision, are referred to with different pronouns in the second person—conveyed in the story with thou/thy/thine/thyself. The story also engages with misgendering, where the keeper refers to the youth with different pronouns in his thoughts than he does when actually addressing the youth. This is uncomfortable to read, but in the narrative, it is clearly intended to be uncomfortable. The ending is melancholy, just like the following story “The Mountains of Sunset, the Mountains of Dawn”—in some senses a companion piece to this one.

“The Mountains of Sunset, the Mountains of Dawn” follows the winged beings who have left their planet and are now traveling in space. Yet they struggle with many of the same dilemmas as the characters of “Wings” who remained behind. Both stories feature a couple with a considerable age gap, a need to choose gender, the difficulty of adapting to one’s physical environment, and issues of embodiment. These are not happy stories, but I found them touching and resonant.

Another theme that threads through the collection is that of collaboration between people of different backgrounds. In “The Genius Freaks”, a woman created to serve humanity with her high intelligence escapes and is aided by an aging man—a very visibly marginalized person in a world of longevity treatments. (Here we also see the first tentative glimmers of cyberpunk, with hacking being an important part of the plot in a dystopian near future.) The novella Screwtop is another example of a similar collaboration, this time between people in a far-future prison camp. Some of them, including one of the main characters, have four biological parents due to a genetic engineering procedure aimed at creating exceptional humans. Others are ordinary humans (as much as people can be “ordinary” in a world where people stow away on spaceships). The main characters form a polyamorous triad of two men and a woman, and are considering inviting another woman to join them… but escape from the camp might be impossible. I enjoyed the character interactions in this novella and thought the environment was very powerfully described. It was also refreshing to read something so matter-of-factly and unapologetically queer—from 1979, no less.

The novella Of Mist, and Grass, and Sand, the first chapter of what would become the novel Dreamsnake, was another highlight of the collection for me. Snake is a human healer crossing the desert on horseback with her three healing snakes, in order to bring a cure to a boy dying from tumors, and relief to his three parents. In this secondary-world setting, a meeting of cultures does not go without problems, but it was such a relief for me to read about people meeting on an equal, respectful footing. The story again avoids the pitfalls of “not filing off the serial numbers”—the cultures shown are obviously not European-based, but they are not quick, off-the-shelf analogs of Earth cultures either. I really appreciated the emphasis on medicine, and the story made me want to pick up Dreamsnake, too.

I felt that the shorter stories in the book were less successful, with strong and heartfelt emotional cores, but with plots that often did not go beyond some variant of “oppression is bad and the characters are suffering.” I found “Only at Night” especially difficult, due to its exaggerated portrayal of disabled children. (This is something characteristic of 1960s-1970s science fiction in general, but it was not a particularly welcome meeting to come across another narrative in this vein.) Another story that has not aged well is “Recourse, Inc.,” with its fight against a computerized bureaucracy—a fight that plays out in an epistolary format. I found myself wondering if I’d read this particular piece previously, or just many others like it.

Buy the Book

Miranda in Milan

But after these occasional speed bumps, the collection ends on another extremely high note: Aztecs, later expanded into the novel Superluminal, is about the struggle of a woman pilot undergoing a surgical procedure to enable her to stay conscious during faster-than-light travel. (The title ties together this surgery with the Aztec practice of sacrificial heart-extraction.) While still recovering, she attempts to start a relationship with a likewise out-of-his-element male crewmember, but nothing quite fits together. Here the queer elements are more subtextual—I was not quite sure even after two rereadings if the protagonist was bisexual, or if I was just imagining that—but in any case, the characters are so fully realized as living, breathing individuals that I would gladly read about anything that happened to them.

This collection sold me on reading two other novels, and just about anything else Vonda N. McIntyre has written in her career. The stories are often sad, often melancholy, or angry, but I never felt like they were one-dimensional or thoughtless. Most of her longer-form work is in print, and I’m not sure why this book hasn’t been made similarly available—but I’d suggest you pick it up if you come across it.

An endnote: I bought and started reading Fireflood before I found out that Vonda N. McIntyre was seriously ill with pancreatic cancer. This post by her ebook publisher both explains how to buy her work, and how to support her in other ways; I suggest that you pay a visit. Which of her books have you read, and which are your favorites?

Bogi Takács is a Hungarian Jewish agender trans person (e/em/eir/emself or singular they pronouns) currently living in the US with eir family and a congregation of books. Bogi writes, reviews and edits speculative fiction, and is currently a finalist for the Hugo, Lambda and Locus awards. You can find em at Bogi Reads the World, and on Twitter and Patreon as @bogiperson.