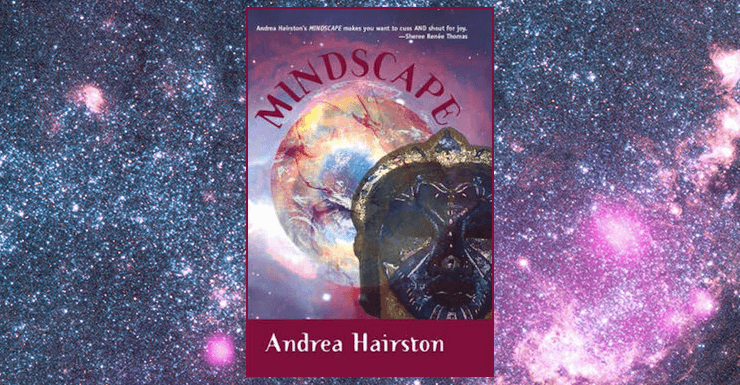

Andrea Hairston’s debut novel Mindscape, published in 2006, won the Carl Brandon Parallax Award and was shortlisted for both the Tiptree and Philip K. Dick awards. It’s also a very explicitly queer book by a queer author, and its Afrofuturist approach pulls no punches. I was surprised that, given all this, there still seems to be relatively little discussion of Mindscape. I can’t speculate whether this is because the book was released by a small publisher (Aqueduct), or if it was ahead of its time, or some other possible reason—but I can provide my own thoughts about the novel, here. I enjoyed it and felt it was original and groundbreaking—but I also had some difficulty with the work, especially with its transgender aspects.

At over 450 relatively large-format pages, Mindscape is a weighty book even before we get to the contents. It presents a sweeping vista of a world still dealing with the aftershocks of alien contact—but not alien contact in the conventional science fictional sense. In Mindscape, the alien presence is a vast Barrier (with a capital B), that moves and changes; it divides Earth into smaller areas, isolating them and only infrequently opening seasonal corridors. It is unclear to what extent the Barrier is sentient, but attempting to cross it results in almost certain death. There are only a handful of people—called Vermittler, after the German word for “go-between”—who can communicate with the Barrier to a limited extent and summon corridors to cross over at will.

Over a hundred years after the appearance of the Barrier, three larger inhabited zones persist: New Ouagadougou, Paradigma, and Los Santos. New Ouagadougou is an Afrofuturist land of spirituality that doesn’t shy away from modernity; Paradigma is a technocratic democracy where the aims often justify the means; and Los Santos is a Wild West version of Hollywood where entertainment is king, and impoverished extras can readily be murdered for the latest movie take. The Interzonal Treaty keeps peace among these areas, but the peace is tenuous, and the Barrier increasingly restless. The Vermittler begin to witness visions of destruction in their minds, while diplomats scramble to preserve the Treaty. Will the Barrier consume the planet?

The story is presented from a number of viewpoints, but probably the most central one is that of Elleni, Vermittler and spirit daughter of Celestina, the Treaty’s architect. As Elleni appears at the center of the narrative, Celestina appears at the margins—at the end of each chapter. We slowly find out what happened to Celestina after she was attacked by an assassin, and the secrets she held in her role as a high-profile politician. Their power relations are reversed compared to their narrative positioning: in-universe, Celestina has been elevated almost to the status of a mythical figure, while most people look down on Elleni. Elleni, like many other Vermittler, has been visibly changed by contact with the Barrier: the braids of her hair are alive, like snakes. She also receives visions as the Barrier communicates with her, and thus to outside observers, her behavior often seems erratic. Yet Elleni is strongheaded and determined.

Many characters are underestimated by the people surrounding them over the course of the story. One of the most poignant examples is Lawanda, a diplomat sent to Los Santos from Paradigma. She is what is called an “ethnic throwback” in this setting: someone who keeps aspects of pre-Barrier Earth cultures alive. Lawanda speaks and writes in a 21st-century African American dialect, and the people around her routinely assume that she is ignorant, naive, and childish, when she is anything but.

Overall, I found the character interactions to be the strongest part of the novel—there are many complicated people in Mindscape, several of whom we also see as point of view characters, and their interactions fit together in complex and yet believable ways. The cast is also very queer. One of the major male characters is bisexual, another is trans—Celestina herself is queer, as well. Vermittler are also matter-of-factly declared to be polyamorous, though not everyone has a positive attitude about this within the narrative.

Mindscape is an extremely ambitious book: it presents not only a new physical world, but also a new spiritual and mental world, as foreshadowed by its title. When characters interact with the Barrier, even the usual familiar dimensions of space and time, or life and death, are no longer what they seem. Characters might teleport large distances, sometimes entirely taken by surprise; they often gain telepathic capabilities, accessing each other’s mindscapes directly—the boundary between magic and science is porous. (Some of the scientific ideas were inspired by the symbiotic planet hypothesis of Lynn Margulis, as described by Hairston in her collection of plays and essays, Lonely Stardust. Margulis herself also provided inspiration for one of the characters in the novel.) All this makes for a fascinating read, but also means that the book is relatively difficult to pick up just for a few pages of casual reading; you need to take the time to become immersed in this world.

I always enjoy seeing Afrofuturist states in fiction (we discussed one in a previous review, too!), and New Ouagadougou especially reminded me of Black Panther’s Wakanda, touching on similar themes of isolationism. There is also all manner of fascinating detail woven into the story: for instance, after a group of European Barrier refugees ended up in New Ouagadougou, the German they spoke became a part of the local culture. (Hairston wrote part of the novel while living in Germany.) It is really interesting to see how German, of all languages, becomes the source for quotable snippets of mystical significance: Was für ein Wunder ist das Leben!

But the scope of the novel is also possibly its greatest challenge. Sometimes the worldbuilding doesn’t quite click—for example, are there no more countries on the planet, beyond just these three? The plot can be hard to follow, and while I’d argue that this is the result of the alternate mindscape afforded by the Barrier, it can also create confusion for the reader: who is where and conspiring against whom, again? I felt that a little bit more contextual grounding at the beginning of chapters could have gone a long way. And, as I mentioned earlier, the queer aspects also didn’t always work for me. While Celestina is a fascinating character and her storyline is a thorough deconstruction of what seems at first to be a simplistic Tragic Queers arc (mini-spoiler: it is not), and it ends on a very satisfying note, not all of the cast get such positive treatment.

Buy the Book

Mindscape

I especially had difficulty with the trans man character whose transness is treated as a spoiler, and whose backstory includes gang rape. In the narrative, transgender is conflated with “transracial” [sic]—not in the sense of transracial adoption, but in the Rachel Dolezal sense. Likewise, being trans is considered similar to being multiple / plural in the sense of more than one person being in one body. Now that trans conversations happen more in the open, it is better known that these are misleading comparisons, but when the book was written, there was less discussion accessible to both cis and trans people alike. I still found the trans aspects of the book frustrating, but there is so much happening in the narrative otherwise that these do not take over the whole novel.

Another issue I had was that, possibly due to the cast being very large, minor characters sometimes came across as one-dimensional. Achbar, the Arab gangster, runs around in a burnoose with a scimitar, and his character only benefits from greater elaboration near the very end. I also found the figure of Jesus Perez, the soybean king and gang leader somewhat baffling: he is set up to be a major antagonist, but then his scenes fizzle out. While this can be realistic—certainly people aren’t always as all-powerful as their reputations might suggest—here, this felt to me more like a technical issue with plotting. I felt similarly toward the Wovoka and Ghost Dancer plotline, which likewise raised many questions that ultimately went unanswered. The book could potentially have worked better as a duology or trilogy: at that length, all the plotlines could have gotten their full due, and the minor characters could have also been given more space without overtaking the narrative. There is so much detail contained in Mindscape, and so much subtlety, that it bursts at the seams. I would be glad to read more about this world, and this interview suggests that Hairston has at least one unpublished manuscript set in the same universe. I could discuss the book endlessly, and probably every reader will find some aspect of this text that really resonates with them. For example, I personally loved seeing how characters reclaimed “throwback;” as a Jewish person with a relatively traditional observance, I have been called my share of similar terms, and it has not occurred to me until now that they could be reclaimed in any way. The book really made me think.

Overall, Mindscape was a fascinating read, despite my occasional struggles with it, and I’ve already started reading my next book by the author, the more recent Lonely Stardust. If you are interested in Mindscape’s themes and its exploration of atypical consciousness, I would strongly recommend that you pick it up. Next time in the column, we will discuss a very different novel that also pushes against boundaries…

Bogi Takács is a Hungarian Jewish agender trans person (e/em/eir/emself or singular they pronouns) currently living in the US with eir family and a congregation of books. Bogi writes, reviews and edits speculative fiction, and is currently a finalist for the Hugo, Lambda and Locus awards. You can find em at Bogi Reads the World, and on Twitter and Patreon as @bogiperson.