A reluctant medium discovers the ties that bind can unleash a dangerous power…

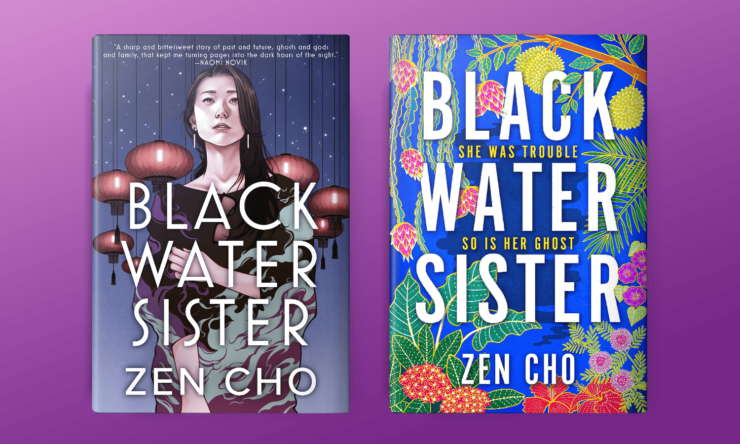

We’re thrilled to share an excerpt from Black Water Sister, a new Malaysian-set contemporary fantasy from author Zen Cho. Black Water Sister publishes May 11th in the US with Ace Books, and will be available in the UK June 10th with Pan Macmillan.

When Jessamyn Teoh starts hearing a voice in her head, she chalks it up to stress. Closeted, broke and jobless, she’s moving back to Malaysia with her parents—a country she last saw when she was a toddler.

She soon learns the new voice isn’t even hers, it’s the ghost of her estranged grandmother. In life, Ah Ma was a spirit medium, avatar of a mysterious deity called the Black Water Sister. Now she’s determined to settle a score against a business magnate who has offended the god—and she’s decided Jess is going to help her do it, whether Jess wants to or not.

Drawn into a world of gods, ghosts, and family secrets, Jess finds that making deals with capricious spirits is a dangerous business, but dealing with her grandmother is just as complicated. Especially when Ah Ma tries to spy on her personal life, threatens to spill her secrets to her family and uses her body to commit felonies. As Jess fights for retribution for Ah Ma, she’ll also need to regain control of her body and destiny—or the Black Water Sister may finish her off for good.

CHAPTER ONE

The first thing the ghost said to Jess was:

Does your mother know you’re a pengkid?

The ghost said it to shock. Unfortunately it had failed to consider the possibility that Jess might not understand it. Jess understood most of the Hokkien spoken to her, but because it was only ever her parents doing the speaking, there were certain gaps in her vocabulary.

Jess didn’t take much notice of the ghost. She might have been more worried if she was less busy, but in a sense, she’d been hearing disapproving voices in her head all her life. Usually it was her mom’s imagined voice lecturing her in Hokkien, but the ghost didn’t sound that different.

Even so, the ghost’s voice stuck with her. The line was still repeating itself in her head the next day, with the persistence of a half-heard advertising jingle.

She was waiting with her mom for the guy from the moving company. Mom was going through the bags of junk Jess had marked for throwing away, examining each object and setting some aside to keep. Jess had spent hours bagging up her stuff; this second go-over was totally unnecessary.

But it was a stressful time for Mom, she reminded herself. It was a huge deal to be moving countries at her age, even if she and Dad called it going home. Back to Malaysia, they said, as though the past nineteen years had been a temporary aberration, instead of Jess’s entire life.

Buy the Book

Black Water Sister

“We said we were going to cut down on our possessions,” Jess said.

“I know,” said Mom. “But this hair band is so nice!” She waved a sparkly pink hair band at Jess. “You don’t want to wear, Min?”

“Dad gave me that when I was ten,” said Jess. “My head’s too big for it now.”

Mom laid the hair band down, grimacing, but she couldn’t quite bring herself to put it back in the garbage bag. Her innate hoarding tendencies had been aggravated by years of financial instability. It seemed almost to give her a physical pain to throw things away.

“Maybe your cousin Ching Yee can wear,” she murmured.

“Ching Yee is older than me,” said Jess. She could feel her voice getting sharp. Patience didn’t come naturally to her. She needed to redirect the conversation.

The line came back to her. Does your mother know you’re a—what?

“Mom,” Jess said in English, “what does ‘pengkid’ mean?”

Mom dropped the hair band, whipping around. “What? Where did you learn that word?”

Startled by the success of her feint, Jess said, “I heard it somewhere. Didn’t you say it?”

Mom stiffened all along her back like an offended cat.

“Mom doesn’t use words like that,” she said. “Whatever friend told you that word, you better not hang out with them so much. It’s not nice to say.”

This struck Jess as hilarious. “None of my friends speak Hokkien, Mom.”

“It’s a Malay word,” said Mom. “I only know is because my colleague told me last time. Hokkien, we don’t say such things.”

“Hokkien doesn’t have any swear words?” said Jess skeptically.

“It’s not a swear word—” Mom cut herself off, conscious she’d betrayed too much, but Jess pounced.

“So what does ‘pengkid’ mean?”

It took some badgering before Mom broke down and told her. Even then she spoke in such vague roundabout terms (“you know, these people . . . they have a certain lifestyle . . .”) that it took a while before Jess got what she was driving at.

“You mean, like a lesbian?” said Jess.

Mom’s expression told her all she needed to know.

After a moment Jess laughed. “I was starting to think it was something really terrible.”

Mom was still in prim schoolmarm mode. “Not nice. Please don’t say such things in front of the relatives.”

“I don’t know what you’re worrying about,” said Jess, bemused. “If they’re anything like you, I’m not going to be saying anything in front of the relatives. They’ll do all the saying.”

“Good,” said Mom. “Better not say anything if you’re going to use such words.”

The hair band lay forgotten on the floor. Jess swept it discreetly into the garbage bag.

“C’mon, focus,” she said. “This is taking forever. Remember they’re coming at four.”

“Ah, Mom is not efficient!” said her mom, flustered. But this acknowledged, she went on at the same snail’s pace as before, picking through each bag as though, with sufficient care, the detritus of Jess’s childhood might be made to yield some extraordinary treasure.

Whatever the treasure was, it wasn’t Jess herself. Everything had boded well when she was a kid. Exemplary grades, AP classes, full ride to an Ivy . . .

But look at her now. Seven months out from college, she was unemployed and going nowhere fast. Everyone she’d known at college was either at some fancy grad school or in a lucrative big-tech job. Meanwhile Jess’s parents had lost all their money and here she was—their one insurance policy, their backup plan—still mooching off them.

“Ah!” cried Mom. She sounded as though she’d discovered the Rosetta stone. “Remember this? Even when you’re small you’re so clever to draw.”

The drawing must have been bundled up with other, less interesting papers, or Jess wouldn’t have thrown it away. Mom had kept every piece of art Jess had ever made, her childhood scrawls treated with as much reverence as the pieces from her first—and last—photography exhibition in her junior year.

The paper was thin, yellow and curly with age. Jess smelled crayon wax as she brought the drawing up to her face, and was hit with an intense shot of nostalgia.

A spindly person stood outside a house, her head roughly level with the roof. Next to her was a smaller figure, its face etched with parallel lines of black tears. They were colored orange, because the child Jess had struggled to find any crayons that were a precise match for Chinese people’s skin.

Both figures had their arms raised. In the sky, at the upper left-hand corner of the drawing, was the plane at which they were waving, flying away.

Jess didn’t remember drawing the picture, but she knew what it was about. “How old was I?”

“Four years old,” said Mom. Her eyes were misty with reminiscence. “That time Daddy still couldn’t get a job in America. Luckily his friend asked Daddy to help out with his company in Kuala Lumpur, but Daddy had to fly back and forth between here and KL. Each time went back for two, three months. Your kindergarten teacher asked me, ‘Is Jessamyn’s father overseas?’ Then she showed me this. I thought, ‘Alamak, cannot like this, Min will get a complex.’ I almost brought you back to Malaysia. Forget America, never mind our green cards. It’s more important for the family to be together.”

Jess touched the drawing, following the teardrops on the child’s face. When was the last time she’d cried? Not when she’d said goodbye to Sharanya, neither of them knowing when they’d see each other again. She’d told a dumb joke and made Sharanya laugh and call her an asshole, tears in her eyes.

Jess must have cried during Dad’s cancer scare. But she couldn’t remember doing it. Only the tearless hours in waiting rooms, stale with exhaustion, Jess staring over Mom’s head as she wept.

“Why didn’t we go back?” said Jess.

“In the end Daddy got a job what,” said Mom. “He was going back and forth for a short time only. It’s not like you were an abandoned child. I was here. You turned out OK.”

The words sounded like an appeal for reassurance. But the tone was strangely perfunctory, as though she was rehearsing a defense she’d repeated many times before.

“You turned out OK,” Mom said again. She took the picture from Jess, smoothing it out and putting it on the pile of things to keep.

“Yeah,” said Jess. She wasn’t sure whom they were trying to convince.

After this, the ghost lay low for a while. It wasn’t like Jess had time to worry about stray voices in her head. Masterminding an intercontinental move crowded everything else out. Her mom, a person to whom all matters were equally important, could probably have gotten it done given three years. Since they had three weeks, it fell on Jess to move things along.

Her dad had gone ahead to Malaysia to start the new job his brother-in-law had arranged for him. He looked tired on their video calls. He’d stopped dyeing his hair after the cancer scare; his head was now almost completely gray. Watching him, Jess noticed for the first time that the skin on his throat hung a little loose, creased with wrinkles. It made him look old.

The sudden disturbing thought came to her: They’ve done it. They did it in the end. After years of insults small and large—misunderstanding his accent, underrating his abilities, dangling opportunities in front of him only to snatch them away—America had finally beaten him.

Jess smothered the thought. Dad was only in his fifties. Asia was rising. This move to Malaysia wasn’t a failure, for Jess or her parents. It was a new beginning.

Her subconscious wasn’t convinced. In the manic run-up to the move, she started having vivid dreams about Malaysia.

At least, she assumed it was Malaysia. The dreams were permeated by overpowering sunshine, an intense glare she had never seen anywhere else. The perpetual sticky heat and vivid greenery were familiar from visits there. But nothing else was familiar.

She was almost always engaged in some mundane task—scrubbing plates, hanging up faded laundry on a clothesline, washing herself with a bucket of gaspingly cold water from a tank. Sometimes there was a baby she was responsible for. It never seemed to stop crying. She found herself staring at its scrunched-up face with stony resentment, hating it but knowing there was nothing to be done.

In one dream she was outdoors, watching her own hands score lines in a tree trunk with a knife. Milky white fluid welled from the gash. Rows of trees stretched out around her.

She had started in the early morning, when it was dark, the air soft and cool on her skin. It grew warmer and brighter as she worked, the light turning silver, then gold. By the time she laid down her tools the heat was all-encompassing, the sun beating mercilessly down.

She carried her harvest to the river, where she paused to scoop water into the pails of white fluid—just enough so the agent wouldn’t be able to tell when he weighed her yield. He still underpaid her. Everyone knew the agent was a cheat, as he knew they sought to cheat him, so that they were all bound by duplicity.

Getting her pay meant she could go to the shop to buy meat, so they’d have something more to eat than plain rice. By the time she got home she was bone tired, but she put the rice on to cook and started chopping the vegetables. She had to get the meal ready before sunset, before night came, before . . .

But Jess didn’t find out what happened at night. She woke up in her sleeping bag, alone in a dark room.

For a moment she didn’t know where she was. They’d shipped or sold off everything in the apartment. Empty, her bedroom looked different, the angles and shadows altered. She might still have been dreaming.

“Mom,” she said later, “you know when you’ve got trees and you cut lines in it so the sap comes out—is that a thing? A Malaysian thing?”

She regretted the question at once. It had made sense in her head, but it sounded like gibberish once the words hit the air. But Mom only nodded, as though it was a perfectly normal thing to ask.

“Rubber tapping?” she said. “Malaysia still produce a lot, but not so much as before. Why?”

“I saw a video somewhere,” said Jess.

She couldn’t recall ever having seen or heard anything about rubber tapping, but her mom must have told her about it sometime. The rustling quiet between the trees, the red-faced baby, her own work-coarsened hands keeping strange rooms clean—they lost their reality in the light of day.

They were just dreams, Jess told herself, the result of her brain processing the move to Malaysia. The rubber tapping must represent her anxiety about her employment prospects—her nostalgia for a time when life was simpler, if harder. Probably the baby was her mom. A therapist would have a field day with her, Jess thought wryly, and forgot all about the dreams.

Excerpted from Black Water Sister, copyright © 2021 by Zen Cho