The Emperor needs necromancers.

The Ninth Necromancer needs a swordswoman.

Gideon has a sword, some dirty magazines, and no more time for undead bullshit.

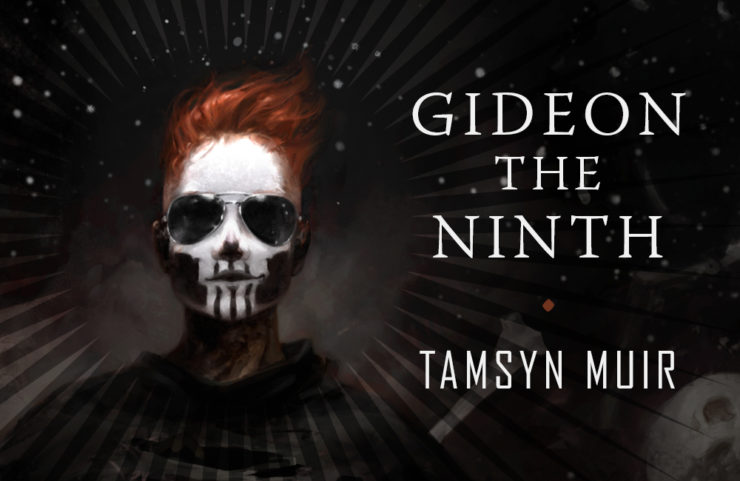

Tamsyn Muir’s heart-pounding epic science fantasy Gideon the Ninth unveils a solar system of swordplay, cut-throat politics, and lesbian necromancers. Available September 10th from Tor.com Publishing, it’s the most fun you’ll ever have with a skeleton. We’re excited to share the first two chapters with you below—what are you waiting for?!

Chapter 1

In the myriadic year of our Lord—the ten thousandth year of the King Undying, the kindly Prince of Death!— Gideon Nav packed her sword, her shoes, and her dirty magazines, and she escaped from the House of the Ninth.

She didn’t run. Gideon never ran unless she had to. In the absolute darkness before dawn she brushed her teeth without concern and splashed her face with water, and even went so far as to sweep the dust off the floor of her cell. She shook out her big black church robe and hung it from the hook. Having done this every day for over a decade, she no longer needed light to do it by. This late in the equinox no light would make it here for months, in any case; you could tell the season by how hard the heating vents were creaking. She dressed herself from head to toe in polymer and synthetic weave. She combed her hair. Then Gideon whistled through her teeth as she unlocked her security cuff, and arranged it and its stolen key considerately on her pillow, like a chocolate in a fancy hotel.

Leaving her cell and swinging her pack over one shoulder, she took the time to walk down five flights to her mother’s nameless catacomb niche. This was pure sentiment, as her mother hadn’t been there since Gideon was little and would never go back in it now. Then came the long hike up twenty-two flights the back way, not one light relieving the greasy dark, heading to the splitoff shaft and the pit where her ride would arrive: the shuttle was due in two hours.

Out here, you had an unimpeded view up to a pocket of Ninth sky. It was soupy white where the atmosphere was pumped in thickest, and thin and navy where it wasn’t. The bright bead of Dominicus winked benignly down from the mouth of the long vertical tunnel. In the dark, she made an opening amble of the field’s perimeter, and she pressed her hands up hard against the cold and oily rock of the cave walls. Once this was done, she spent a long time methodically kicking apart every single innocuous drift and hummock of dirt and rock that had been left on the worn floor of the landing field. She dug the shabby steel toe of her boot into the hard-packed floor, but satisfied with the sheer improbability of anyone digging through it, left it alone. Not an inch of that huge, empty space did Gideon leave unchecked, and as the generator lights grumbled to half-hearted life, she checked it twice by sight. She climbed up the wire-meshed frames of the floodlights and checked them too, blinded by the glare, feeling blindly behind the metal housing, grimly comforted by what she didn’t find.

She parked herself on one of the destroyed humps of rubble in the dead centre. The lamps made lacklustre any real light. They explosively birthed malform shadow all around. The shades of the Ninth were deep and shifty; they were bruise-coloured and cold. In these surrounds, Gideon rewarded herself with a little plastic bag of porridge. It tasted gorgeously grey and horrible.

Buy the Book

Gideon the Ninth

The morning started as every other morning had started in the Ninth since the Ninth began. She took a turn around the vast landing site just for a change of pace, kicking absently at an untidy drift of grit as she went. She moved out to the balcony tier and looked down at the central cavern for signs of movement, worrying porridge from her molars with the tip of her tongue. After a while, there was the faraway upward clatter of the skeletons going to pick mindlessly at the snow leeks in the planter fields. Gideon saw them in her mind’s eye: mucky ivory in the sulfurous dim, picks clattering over the ground, eyes a multitude of wavering red pinpricks.

The First Bell clanged its uncanorous, complaining call for beginning prayers, sounding as always like it was getting kicked down some stairs; a sort of BLA-BLANG… BLA-BLANG… BLA-BLANG that had woken her up every morning that she could recall. Move-ment resulted. Gideon peered down at the bottom where shadows gathered over the cold white doors of Castle Drearburh, stately in the dirt, set into the rock three bodies wide and six bodies tall. Two braziers stood on either side of the door and perpetually burned fatty, crappy smoke. Over the doors were tiny white figures in a multitude of poses, hundreds to thousands of them, carved using some weird trick where their eyes seemed to look right at you. Whenever Gideon had been made to go through those doors as a kid, she’d screamed like she was dying.

More activity in the lowest tiers now. The light had settled into visibility. The Ninth would be coming out of their cells after morning contemplation, getting ready to head for orison, and the Drear-burh retainers would be preparing for the day ahead. They would perform many a solemn and inane ritual in the lower recesses. Gideon tossed her empty porridge bag over the side of the tier and sat down with her sword over her knees, cleaning it with a bit of rag: forty minutes to go.

Suddenly, the unchanging tedium of a Ninth morning changed. The First Bell sounded again: BLANG… BLA-BLANG… BLA-BLANG… Gideon cocked her head to listen, finding her hands had stilled on her sword. It rang fully twenty times before stopping. Huh; muster call. After a while came the clatter of the skeletons again, having obediently tossed down pick and hoe to meet their summons. They streamed down the tiers in an angular current, broken up every so often by some limping figure in vestments of rusting black. Gideon picked up her sword and cloth again: it was a cute try, but she wasn’t buying.

She didn’t look up when heavy, stumping footsteps sounded on her tier, or for the rattle of rusting armour and the rusty rattle of breath.

“Thirty whole minutes since I took it off, Crux,” she said, hands busy. “It’s almost like you want me to leave here forever. Ohhhh shit, you absolutely do though.”

“You ordered a shuttle through deception,” bubbled the marshal of Drearburh, whose main claim to fame was that he was more decrepit alive than some of the legitimately dead. He stood before her on the landing field and gurgled with indignation. “You falsified documents. You stole a key. You removed your cuff. You wrong this house, you misuse its goods, you steal its stock.”

“Come on, Crux, we can come to some arrangement,” Gideon coaxed, flipping her sword over and looking at it critically for nicks. “You hate me, I hate you. Just let me go without a fight and you can retire in peace. Take up a hobby. Write your memoirs.”

“You wrong this house. You misuse its goods. You steal its stock.” Crux loved verbs.

“Say my shuttle exploded. I died, and it was such a shame. Give me a break, Crux, I’m begging you here—I’ll trade you a skin mag. Frontline Titties of the Fifth.” This rendered the marshal momentarily too aghast to respond. “Okay, okay. I take it back. Frontline Titties isn’t a real publication.”

Crux advanced like a glacier with an agenda. Gideon rolled backward off her seat as his antique fist came down, skidding out of his way with a shower of dust and gravel. Her sword she swiftly locked within its scabbard, and the scabbard she clutched in her arms like a child. She propelled herself backward, out of the way of his boot and his huge, hoary hands. Crux might have been very nearly dead, but he was built like gristle with what seemed like thirty knuckles to each fist. He was old, but he was goddamn ghastly.

“Easy, marshal,” she said, though she was the one floundering in the dirt. “Take this much further and you’re in danger of enjoying yourself.”

“You talk so loudly for chattel, Nav,” said the marshal. “You chatter so much for a debt. I hate you, and yet you are my wares and inventory. I have written up your lungs as lungs for the Ninth. I have measured your gall as gall for the Ninth. Your brain is a base and shrivelled sponge, but it too is for the Ninth. Come here, and I’ll black your eyes for you and knock you dead.”

Gideon slid backward, keeping her distance. “Crux,” she said, “a threat’s meant to be ‘Come here, or…’”

“Come here and I’ll black your eyes for you and knock you dead,” croaked the advancing old man, “and then the Lady has said that you will come to her.”

Only then did Gideon’s palms prickle. She looked up at the scarecrow towering before her and he stared back, one-eyed, horrible, baleful. The antiquated armour seemed to be rotting right off his body. Even though the livid, over-stretched skin on his skull looked in danger of peeling right off, he gave the impression that he simply wouldn’t care. Gideon suspected that—even though he had not a whit of necromancy in him—the day he died, Crux would keep going anyway out of sheer malice.

“Black my eyes and knock me dead,” she said slowly, “but your Lady can go right to hell.”

Crux spat on her. That was disgusting, but whatever. His hand went to the long knife kept over one shoulder in a mould-splattered sheath, which he twitched to show a thin slice of blade: but at that, Gideon was on her feet with her scabbard held before her like a shield. One hand was on the grip, the other on the locket of the sheath. They both faced each other in impasse, her very still, the old man’s breath loud and wet.

Gideon said, “Don’t make the mistake of drawing on me, Crux.”

“You are not half as good with that sword as you think you are, Gideon Nav,” said the marshal of Drearburh, “and one day I’ll flay you for disrespect. One day we will use your parts for paper. One day the sisters of the Locked Tomb will brush the oss with your bristles. One day your obedient bones will dust all places you disdain, and make the stones there shine with your fat. There is a muster, Nav, and I command you now to go.”

Gideon lost her temper. “You go, you dead old dog, and you damn well tell her I’m already gone.”

To her enormous surprise he wheeled around and stumped back to the dark and slippery tier. He rattled and cursed all the way, and she told herself that she had won before she even woke up that morning; that Crux was an impotent symbol of control, one last attempt to test if she was stupid enough or cowed enough to walk back behind the cold bars of her prison. The grey and putrid heart of Drearburh. The greyer and more putrid heart of its lady.

She pulled her watch out of her pocket and checked it: twenty minutes to go, a quarter hour and change. Gideon was home free. Gideon was gone. Nothing and nobody could change that now.

“Crux is abusing you to anyone who will listen,” said a voice from the entryway, with fifteen minutes to go. “He said you made your blade naked to him. He said you offered him sick pornographies.”

Gideon’s palms prickled again. She’d sat back down on her awkward throne of rocks and balanced her watch between her knees, staring at the tiny mechanical hand that counted the minutes. “I’m not that dumb, Aiglamene,” she said. “Threaten a house official and I wouldn’t make toilet-wiper in the Cohort.”

“And the pornography?”

“I did offer him stupendous work of a titty nature, and he got offended,” said Gideon. “It was a very perfect moment. The Cohort’s not going to care about that though. Have I mentioned the Cohort? You do know the Cohort, right? The Cohort I’ve left to enlist in… thirty-three times?”

“Save the drama, you baby,” said her sword-master. “I know of your desires.”

Aiglamene dragged herself into the small light of the landing field. The captain of the House guard had a head of melty scars and a missing leg which an indifferently talented bone adept had replaced for her. It bowed horribly and gave her the appearance of a building with the foundations hastily shored up. She was younger than Crux, which was to say, old as balls: but she had a quickness to her, a liveliness, that was clean. The marshal was classic Ninth and he was filthy rotten all the way through.

“Thirty-three times,” repeated Gideon, somewhat wearily. She checked back on her clockwork: fourteen minutes to go. “The last time, she jammed me in the lift. The time before that she turned off the heating and I got frostbite in three toes. Time before that: she poisoned my food and had me crapping blood for a month. Need I go on.”

Her teacher was unmoved. “There was no disservice done. You didn’t get her permission.”

“I’m allowed to apply for the military, Captain. I’m indentured, not a slave. I’m no fiscal use to her here.”

“Beside the point. You chose a bad day to fly the coop.” Aiglamene jerked her head downward. “There’s House business, and you’re wanted downstairs.”

“This is her being sad and desperate,” said Gideon. “This is her obsession… this is her need for control. There’s nothing she can do. I’ll keep my nose clean. Keep my mouth shut. I’ll even—you can write this down, you can quote me here—do my duty to the Ninth House. But don’t pretend at me, Aiglamene, that the moment I go down there a sack won’t come down over my head and I won’t spend the next five weeks concussed in an oss.”

“You egotistical foetus, you think our Lady rang the muster call just for you?”

“So, here’s the thing, your Lady would set the Locked Tomb on fire if it meant I’d never see another sky,” Gideon said, looking up. “Your Lady would stone cold eat a baby if it meant she got to lock me up infinitely. Your Lady would slather burning turds on the great-aunts if she thought it would ruin my day. Your Lady is the nastiest b—”

When Aiglamene slapped her, it had none of the trembling affrontedness Crux might have slapped her with. She simply back-handed Gideon the way you might hit a barking animal. Gideon’s head was starry with pain.

“You forget yourself, Gideon Nav,” her teacher said shortly. “You’re no slave, but you’ll serve the House of the Ninth until the day you die and then thereafter, and you’ll commit no sin of perfidy in my air. The bell was real. Will you come to muster of your own accord, or will you disgrace me?”

There was a time when she had done many things to avoid disgracing Aiglamene. It was easy to be a disgrace in a vacuum, but she had a soft spot for the old soldier. Nobody had ever loved her in the House of the Ninth, and certainly Aiglamene did not love her and would have laughed herself to her overdue death at the idea: but in her had been a measure of tolerance, a willingness to loosen the leash and see what Gideon could do with free rein. Gideon loved free rein. Aiglamene had convinced the House to put a sword in Gideon’s hands, not to waste her on serving altar or drudging in the oss. Aiglamene wasn’t faithless. Gideon looked down and wiped her mouth with the back of her hand, and saw the blood in her saliva and saw her sword; and she loved her sword so much she could frigging marry it.

But she also saw her clock’s minute hand ticking, ticking down. Twelve minutes to go. You didn’t cut loose by getting soft. For all its mouldering brittleness, the Ninth was hard as iron.

“I guess I’ll disgrace you,” Gideon admitted easily. “I feel like I was born to it. I’m naturally demeaning.”

Her sword-master held her gaze with her aged hawk’s face and her pouchy socket of an eye, and it was grim, but Gideon didn’t look away. It would have made it somewhat easier if Aiglamene had made a Crux out of it and cursed her lavishly, but all she said was: “Such a quick study, and you still don’t understand. That’s on my head, I suppose. The more you struggle against the Ninth, Nav, the deeper it takes you; the louder you curse it, the louder they’ll have you scream.”

Back straight as a poker, Aiglamene walked away with her funny seesawing walk, and Gideon felt as though she’d failed a test. It didn’t matter, she told herself. Two down, none to go. Eleven minutes until landing, her clockwork told her, eleven minutes and she was out. That was the only thing that mattered. That was the only thing that had mattered since a much younger Gideon had realised that, unless she did something drastic, she was going to die here down in the dark.

And—worst of all—that would only be the beginning.

Nav was a Niner name, but Gideon didn’t know where she’d been born. The remote, insensate planet where she lived was home to both the stronghold of the House and a tiny prison, used only for those criminals whose crimes were too repugnant for their own Houses to rehabilitate them on home turf. She’d never seen the place. The Ninth House was an enormous hole cracked vertically into the planet’s core, and the prison a bubble installation set halfway up into the atmosphere where the living conditions were probably a hell of a lot more clement.

One day eighteen years ago, Gideon’s mother had tumbled down the middle of the shaft in a dragchute and a battered hazard suit, like some moth drifting slowly down into the dark. The suit had been out of power for a couple of minutes. The woman landed brain-dead. All the battery power had been sucked away by a bio-container plugged into the suit, the kind you’d carry a transplant limb in, and inside that container was Gideon, only a day old.

This was obviously mysterious as hell. Gideon had spent her life poring over the facts. The woman must have run out of juice an hour before landing; it was impossible that she would have cleared gravity from a drop above the planet, as her simple haz would have exploded. The prison, which recorded every coming and going obsessively, denied her as an escapee. Some of the nun-adepts of the Locked Tomb were sent for, those who knew the secrets for caging ghosts. Even they—old in their power then, seasoned necromancers of the dark and powerful House of the Ninth—couldn’t rip the woman’s shade back to explain herself. She would not be tempted back for fresh blood or old. She was too far gone by the time the exhausted nuns had tethered her by force, as though death had been a catalyst for the woman to hit the ground running, and they only got one word out of her: she had screamed Gideon! Gideon! Gideon! three times, and fled.

If the Ninth—enigmatic, uncanny Ninth, the House of the Sewn Tongue, the Anchorite’s House, the House of Heretical Secrets—was nonplussed at having an infant on their hands, they moved fast anyway. The Ninth had historically filled its halls with penitents from other houses, mystics and pilgrims who found the call of this dreary order more attractive than their own birthrights. In the antiquated rules of those supplicants who moved between the eight great households, she was taken as a very small bondswoman, not of the Ninth but beholden to it: what greater debt could be accrued than that of being brought up? What position more honourable than vassal to Drearburh? Let the baby grow up postulant. Push the child to be an oblate. They chipped her, surnamed her, and put her in the nursery. At that time, the tiny Ninth House boasted two hundred children between infancy and nineteen years of age, and Gideon was numbered two hundred and first.

Less than two years later, Gideon Nav would be one of only three children left: herself, a much older boy, and the infant heir of the Ninth House, daughter of its lord and lady. They knew by age five that she was not a necromancer, and suspected by eight that she would never be a nun. Certainly, they would have known by ten that she knew too much, and that she could never be allowed to go.

Gideon’s appeals to better natures, financial rewards, moral obligations, outlined plans, and simple attempts to run away numbered eighty-six by the time she was eighteen. She’d started when she was four.

Chapter 2

There were five minutes to go when Gideon’s eighty-seventh escape plan got messed up fantastically.

“I see that your genius strategy, Griddle,” said a final voice from the tierway, “was to order a shuttle and walk out the door.”

The Lady of the Ninth House stood before the drillshaft, wearing black and sneering. Reverend Daughter Harrowhark Nonagesimus had pretty much cornered the market on wearing black and sneering. It comprised 100 percent of her personality. Gideon marvelled that someone could live in the universe only seventeen years and yet wear black and sneer with such ancient self-assurance.

Gideon said, “Hey, what can I say? I’m a tactician.”

The ornate, slightly soiled robes of the House dragged in the dust as the Reverend Daughter approached. She’d brought her marshal along, and Aiglamene too. A few Sisters were behind her on the tier, having sunk down to their knees: the cloisterwomen painted their faces alabaster grey and drew black patterns on their cheeks and lips like death’s-heads. Dressed in breadths of rusty black cloth, they looked like a peanut gallery of sad old waist-high masks.

“It’s embarrassing that it had to come to this,” said the Lady of the Ninth, pulling back her hood. Her pale-painted face was a white blotch among all the black. Even her hands were gloved. “I don’t care that you run away. I care that you do it badly. Take your hand from your sword, you’re humiliating yourself.”

“In under ten minutes a shuttle’s going to come and take me to Trentham on the Second,” Gideon said, and did not take her hand from her sword. “I’m going to get on it. I’m going to close the door. I’m going to wave goodbye. There is literally nothing you can do anymore to stop me.”

Harrow put one gloved hand before her and massaged her fingers thoughtfully. The light fell on her painted face and black-daubed chin, and her short-cropped, dead-crow-coloured hair. “All right. Let’s play this one through for interest’s sake,” she said. “First objection: the Cohort won’t enlist an unreleased serf, you know.”

“I faked your signature on the release form,” said Gideon.

“But a single word from me and you’re brought back in cuffs.”

“You’ll say nothing.”

Harrowhark ringed two fingers around one wrist and slowly worked the hand up and down. “It’s a cute story, but badly characterised,” she said. “Why the sudden mercy on my part?”

“The moment you deny me leave to go,” said Gideon, hand unmoving on her scabbard, “the moment you call me back—the moment you give the Cohort cause, or, I don’t know, some list of trumped-up criminal charges… ”

“Some of your magazines are very nasty,” admitted the Lady.

“That’s the moment I squeal,” said Gideon. “I squeal so long and so loud they hear me from the Eighth. I tell them everything. You know what I know. And I’ll tell them the numbers. They’d bring me home in cuffs, but I’d come back laughing my ass off.”

At that, Harrowhark stopped working her scaphoid and glanced at Gideon. She gave a rather brusque hand-wave to the geriatric fan club behind her and they scattered: tottering, kissing the floor and rattling both their prayer beads and their unlubricated knee joints, disappearing into the darkness and down the tier. Only Crux and Aiglamene stayed. Then Harrow cocked her head to the side like a quizzical bird and smiled a tiny, contemptuous smile.

“How coarse and ordinary,” she said. “How effective, how crass. My parents should have smothered you.”

“I’d like to see them try it now,” said Gideon, unmoved.

“You’d do it even if there was no ultimate gain,” the Lady said, and she even seemed to be marvelling at it. “Even though you know what you’d suffer. Even though you know what it means. And all because…?”

“All because,” said Gideon, checking her clock again, “I completely fucking hate you, because you are a hideous witch from hell. No offence.”

There was a pause.

“Oh, Griddle!” said Harrow pityingly, in the silence. “But I don’t even remember about you most of the time.”

They stared at each other. There was a lopsided smile tugging at Gideon’s mouth, unsuppressed, and looking at it made Harrowhark’s expression slide into something even moodier and more petulant. “You have me at an impasse,” she said, and she sounded grudgingly amazed by the fact. “Your ride will be here in five minutes. I don’t doubt you have all the documents and that they look good. It’d be master’s sin if I employed unwarranted violence. There is really nothing I can do.”

Gideon said nothing. Harrow said, “The muster call is real, you know. There’s important Ninth business afoot. Won’t you give a handful of minutes to take part in your House’s last muster?”

“Oh hell no,” said Gideon.

“Can I appeal to your deep sense of duty?”

“Nope,” said Gideon.

“Worth a try,” admitted Harrow. She tapped her chin thoughtfully. “What about a bribe?”

“This is going to be good,” said Gideon to nobody in particular. “‘Gideon, here’s some money. You can spend it right here, on bones.’ ‘Gideon, I’ll always be nice and not a dick to you if you come back. You can have Crux’s room.’ ‘Gideon, here’s a bed of writhing babes. It’s the cloisterites, though, so they’re ninety percent osteoporosis.’”

From out of her pocket, with no small amount of drama, Harrowhark drew a fresh piece of parchment. It was paper—real paper!—with the official letterhead of the House of the Ninth on the top. She must have raided the coffers for that one. The hairs on the back of Gideon’s neck prickled in warning. Harrow ostentatiously walked forward to leave it at a safe middle point between them both, and backed away with hands open in surrender.

“Or,” said the Lady, as Gideon slowly went to pick it up, “it could be an absolutely authentic purchase of your commission in the Cohort. You can’t forge this, Griddle, it’s to be signed in blood, so don’t stuff it down your trousers yet.”

It was real Ninth bond, written correctly and clearly. It purchased Gideon Nav’s commission to second lieutenant, not privy to resale, but relinquishing capital if she honourably retired. It would grant her full officer training. The usual huge percentage of prizes and territory would be tithed to her House if they were won, but her inflated Ninth serfdom would be paid for in five years on good conditions, rather than thirty. It was more than generous. Harrow was shooting herself in the foot. She was gamely firing into one foot and then taking aim at the other. She’d lose rights to Gideon forever. Gideon went absolutely cold.

“You can’t say I don’t care,” said Harrow.

“You don’t care,” said Gideon. “You’d have the nuns eat each other if you got bored. You are a psychopath.”

Harrow said, “If you don’t want it, return it. I can still use the paper.”

The only sensible option was to fold the bond into a dart and sail it back the way it came. Four minutes until the shuttle landed and she was able to make hot tracks far away from this place. She’d already won, and this was a vulnerability that would put everything she’d worked for—months of puzzling out how to infiltrate the shuttle standing-order system, months to hide her tracks, to get the right forms, to intercept communications, to wait and sweat— into jeopardy. It was a trick. And it was a Harrowhark Nonagesimus trick, which meant it was going to be atrociously nasty—

Gideon said, “Okay. Name your price.”

“I want you downstairs at the muster meeting.”

She didn’t bother to hide her amazement. “What are you announcing, Harrow?”

The Reverend Daughter remained smileless. “Wouldn’t you like to know.”

There was a long moment. Gideon let a long breath escape through her teeth, and with a heroic effort, she dropped the paper on the ground and backed away. “Nah,” she said, and was interested to see a tiny beetling of the Lady’s black eyebrows. “I’ll go my own way. I’m not going down into Drearburh for you. Hell, I’m not going down into Drearburh if you get my mother’s skeleton to come do a jig for me.”

Harrow bunched her gloved hands into fists and lost her composure. “For God’s sake, Griddle! This is the perfect offer! I am giving you everything you’ve ever asked for—everything you’ve whined for so incessantly, without you even needing to have the grace or understanding to know why you couldn’t have it! You threaten my House, you disrespect my retainers, you lie and cheat and sneak and steal—you know full well what you’ve done, and you know that you are a disgusting little cuckoo!”

“I hate it when you act like a butt-touched nun,” said Gideon, who was only honestly sorry for one of the things in that lineup.

“Fine,” snarled Harrowhark, now in every appearance of a fine temper. She was struggling out of her long, ornate robes, the human ribcage she wore clasped around her long torso shining whitely against the black. Crux cried out in dismay as she began to detach the little silver snaps that held it to her chest, but she silenced him with a curt gesture as she took it off. Gideon knew what she was doing. A great wave of commingled pity and disgust moved through her as she watched Harrow take off her bone bracelets, the teeth she kept at her neck, the little bone studs in her ears. All these she dumped in Crux’s arms, stalking back to the shuttlefield and presenting herself like an emptied quiver. Just in gloves and boots and shirt and trousers, with her cropped black head and her face pinched with wrath, she seemed like what she really was: a desperate girl younger than Gideon, and rather small and feeble.

“Look, Nonagesimus,” said Gideon, thoroughly unbalanced and now actually embarrassed, “cut the bull. Don’t do—whatever you’re about to do. Let me go.”

“You don’t get to turn and leave quite so easily, Nav,” said Harrowhark, with palpable chill.

“You want your ass kicked by way of goodbye?”

“Shut up,” said the Lady of the Ninth, and, horrifyingly: “I’ll alter the terms. A fair fight and—”

“—and I leave scot free? I’m not that stupid—”

“No. A fair fight and you can go with the commission,” said Harrow. “If I win, you come to the muster, and you leave afterward— with the commission. If I lose, you leave now—with the commission.” She snatched the paper from the ground, pulled a fountain pen from her pocket, and slid it between her lips to stab it deeply into her cheek. It came out thick with blood—one of her party tricks, Gideon thought numbly—and signed: Pelleamena Novenarius, Reverend Mother of the Locked Tomb, Lady of Drearburh, Ruler of the Ninth House.

Gideon said, feeling idiotic: “That’s your mother’s signature.”

“I’m not going to sign as me, you utter moron, that would give the whole game away,” said Harrow. This close, Gideon could see the red starbursts at the corners of her eyes, the pink smears of someone who hadn’t slept all night. She held out the commission and Gideon snatched it with shameless hunger, folding it up and shoving it down her shirt and into her bandeau. Harrow didn’t even smirk. “Agree to duel me, Nav, in front of my marshal and guard. A fair fight.”

Above all else Harrowhark was a skeleton-maker, and in her rage and pride she was offering an unfair fight instead. The thoroughbred Ninth adept had unmanned herself by starting a fight with no body to raise and not even a bone button to help her. Gideon had seen Harrow in this mood only once before, and had thought she would probably never see her in this mood again. Only a complete asshole would agree to such a duel, and Harrowhark knew it. It would take a dyed-in-the-wool douchebag. It would be an embarrassing act of cruelty.

“If I lose, I go to your meeting and leave with the commission,” said Gideon.

“Yes.”

“If I win, I go with the commission now,” said Gideon.

Blood flecked Harrow’s lips. “Yes.”

Overhead, a roar of displaced air. A searchlight flickered over the drillshaft as the shuttle, finally making its descent, approached the wound in the planet’s mantle. Gideon checked her clock. Two minutes. Without a moment’s hesitation, she patted the Reverend Daughter down: arms, midsection, legs, a quick clutch around the boots. Crux cried out again in disgust and dismay at the sight. Harrow said nothing, which was more contemptuous than anything she could have said. But you didn’t get anywhere through softness. The House was hard as iron. You smashed iron where it was weak.

“You all heard her,” she said to Crux, to Aiglamene. Crux stared back at her with the hate of an exploding star: the empty hate of pressure pulled inward, a deforming, light-devouring resentment. Aiglamene refused to meet her gaze. That sucked, but fine. Gideon started digging around in her pack for her gloves. “You heard her. You witnessed. I’m going either way, and she offered the terms. Fair fight. You swear by your mother it’s a fair fight?”

“How dare you, Nav—”

“By your mother. And to the floor.”

“I swear by my mother. I have nothing on me. To the floor,” snapped Harrow, breath coming in staccato pants of anger. As Gideon hastily slipped on her polymer mitts, flipping the thick clasps shut at the wrists, her smile twisted. “My God, Griddle, you’re not even wearing leather. I’m hardly that good.”

They stepped away from each other, Aiglamene finally raised her voice over the growing noise of the shuttle: “Gideon Nav, take back your honour and give your lady a weapon.”

Gideon couldn’t help herself: “Are you asking me to… throw her a bone?”

“Nav!”

“I gave her my whole life,” said Gideon, and unsheathed her blade.

The sword was really just a gesture. What ought to have happened was that Gideon raised a booted foot and knocked Harrow ass-over-tits, hard enough to prevent the Lady of the Ninth embarrassing herself by getting up over and over and over. A booted foot on Harrow’s stomach and it would have all been done. She would have sat on Harrow if she’d needed to. No one in the Ninth House understood what cruelty was, not really, none of them but the Reverend Daughter; none of them understood brutality. The knowledge had been dried out of them, evaporated by the dark that pooled at the bottom of Drearburh’s endless catacombs. Aiglamene or Crux would have had to call it a fair fight won, and Gideon would have walked away a nearly-free woman.

What happened was that Harrowhark peeled off her gloves. Her hands were wrecked. The fingers were riddled with dirt and oozing cuts, and grit stuck in the wounds and beneath the messed-up nails. She dropped the gloves and wiggled her fingers in Gideon’s direction, and Gideon had a split second to realise that it was drillshaft grit, and that she was absolutely boned in all directions.

She charged. It was too late. Next to the drifts of dirt and stone that she had carefully kicked apart, skeletons burst out of the hard earth where they had been hastily interred. Hands erupted from little pockets in the ground, perfect, four-fingered and thumbed; Gideon, stupid with assumption, kicked them off and careened sideways. She ran. It didn’t matter: every five feet—every five god-damned feet—bones burst from the ground, grasping her boots, her ankles, her trousers. She staggered away, desperate to find the limits of the field: there were none. The floor of the drillshaft was erupting in fingers and wrists, waving gently, as though buffeted by the wind.

Gideon looked at Harrow. Harrow was breaking out in blood sweat, and her returned stare was calm and cold and assured.

She plunged back toward the Lady of Drearburh with an incoherent yell, smashing carpals and metacarpals to bits as she ran, but it didn’t matter. From as little as a buried femur, a hidden tibia, skeletons formed for Harrow in perfect wholeness, and as Gideon neared their mistress a tidal wave of reanimated bones crested down on her. Her booted foot knocked Harrow into the arms of two of her creations, who carted her easily out of harm’s way. Harrowhark’s unperturbed gaze disappeared behind a blur of fleshless men, of femur and tibia and supernaturally quick grasp. Gideon used her sword like a lever, showering herself in chips of bone and cartilage and trying to make each cut count, but there were too many of them. There were just so many. Replacements rose even as she pulverized them into rains of bone. More and more cannonballed her down to the ground, no matter in what direction she lurched, from the fruits of the morbid garden Harrow had sowed.

The roar of the shuttle drowned out the clattering of bones and the blood in her ears as she was grabbed by dozens of hands. Harrowhark’s talent had always been in scale, in making a fully realised construct from as little as an arm bone or a pelvis, able to make an army of them from what anyone else would need for one, and in some far-off way Gideon had always known that this would be how she went: gangbanged to death by skeletons. The melee melted away to admit a booted foot that knocked her down. The bone men held her to the earth as she reared up, spitting and bleeding, to find Harrow: tucked between her grinning minions, pensive, serene. Harrowhark kicked Gideon in the face.

For a couple of seconds everything was red and black and white. Gideon’s head lolled to the side as she coughed out a tooth, choking, thrashing to rise. The boot pressed itself to her throat, then down and down and down, forcing her back into the hard grit floor. The shuttle’s descent whipped up a storm of stinging dust, sending some of the skeletons flying. Harrow discarded them and they rattled into still, anatomical piles.

“It’s pathetic, Griddle,” said the Lady of the Ninth. Bones were shedding from her minions now after the initial adrenaline rush: peeling off and falling inert to earth, an arm there, a jawbone here, as they wobbled out of shape. She’d pushed herself very hard. Radiating out from them was a circle of burst pockets in the hard ground, like tiny exploded mines. She stood among her holes with a hot, bloody face and trickling nosebleed, and indifferently wiped her face with her forearm.

“It’s pathetic,” she repeated, slightly thick with blood. “I turn up the volume. I put on a show. You feel bad. You make it so easy. I got more hot and bothered digging all night.”

“You dug,” wheezed Gideon, rather muffled with grit and dust, “all night.”

“Of course. This floor’s hard as hell, and there’s a lot to cover.”

“You insane creep,” said Gideon.

“Call it, Crux,” ordered Harrowhark.

It was with poorly hidden glee that her marshal called out, “A fair fight. The foe is floored. A win for the Lady Nonagesimus.”

The Lady Nonagesimus turned back to her two retainers and raised her arms up for her discarded robe to be slipped back around her shoulders. She coughed a small knot of blood up into the dirt and waved Crux off as he hovered about her. Gideon lifted her head, then let it fall back hard on the grit floor, dazed and cold. Aiglamene was looking at her now with an expression she couldn’t parse. Sympathy? Disappointment? Guilt?

The shuttle connected its docking feet to the ground, crunching hard into the floor. Gideon looked at it—its gleaming sides, its steaming engine vents—and tried to pull herself up on her elbows. She couldn’t; she was too winded still. She couldn’t even raise a shaking middle finger to the victor: she just kept looking at the shuttle, and her suitcase, and her sword.

“Buck up, Griddle,” Harrowhark was saying. She spat another clot out on the ground, close to Gideon’s head. “Captain, go and tell the pilot to sit and wait: he’ll get paid for his time.”

“What if he asks after his passenger, my lady?” God bless Aiglamene.

“She’s been delayed. Tell him he’ll stand by on my grace for an hour, with apologies. My parents have been waiting long enough, and this took somewhat longer than I thought it would. Marshal, get her down to the sanctuary—”

Excerpted from Gideon the Ninth, copyright © 2019 by Tamsyn Muir.