On the nesting Matryoshka dolls of space-faring civilizations, philosophy a la Nietzsche, and how Banks ruined SF and epic fantasy at the same time for me.

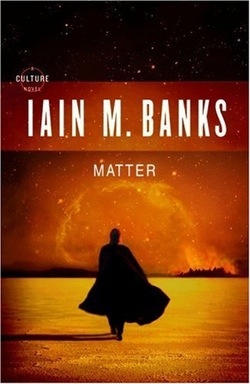

Matter is one of Banks’ loosely set Culture novels. As a rule they’re Big Idea tales that ruthlessly use mechanisms unique to science fiction to explore said ideas. Written years after the last Culture novel, Matter not only retains the virility of the acclaimed Use of Weapons, but intensifies it. His world-building is more glorious and mind-bending than before, his ideas more encompassing and disturbing.

But in Matter, the main idea is colder and more distant than ever before. As a consequence, character and plot, always more vehicles than not in Banks’ books, are consumed entirely by this Idea, which asks the question:

“Life: what’s the point?”

Normally the question is interpreted as a personal reflection and self-discovery. But in Matter, the question is asked not just on the level of the individual, but also on the level of entire civilizations.

Banks, of course, never makes this interpretation easy.

The “Culture” that gives the series its name is itself an extremely advanced society—of meddlers. Into the depths of the politics and development of technologically inferior races they tread, with results sometimes fortunate, sometimes not, often both, always disturbing to think about. With ultimate power comes ultimate responsibility, the very definition of the Culture.

Other civilizations also wish to emulate the Culture, thinking that they’re climbing up the ladder of racial superiority, not knowing—or, sometimes, caring—about the terrible cost that such tinkering can bring. In Matter, we end up with a Matryoshka nest of civilizations, each wielding influence on their “smaller” wards.

At the unfortunate center of this particular nesting is a medieval-level culture. Which annoys the hell out of some readers expecting a more futuristic tale, even though these passages alternate with ye olde style Banks Culture chapters. I found this part of the story interesting, however, because they’re executed with a flair comparable to that of George R. R. Martin or David Anthony Durham. In fact, all by themselves these chapters would have made an intriguing tale, with the grit of A Song of Ice and Fire or Acacia, and seemingly random fantastical flourishes replaced with science fiction ones—for these people are quite aware of the power of civilizations above them in the Matryoshka, even if their understanding is incomplete.

The traditionally SFnal point of view in the books is still tied to this culture, in fact: a royal princess who was taken away and raised as part of the capital-C Culture itself. I particularly liked her, with her cool and sarcastic personality, strong and distanced and yet not a caricature of the Strong Female Character. In her history and development is the contrast between the topmost Culture and the bottommost of her home, between a society that allows her to explore her full potential and beyond, and one that would have a hard time with the idea of a female on the throne.

For a book with such a nihilistic theme, the story is alive in so many ways, with character growth and development (even of the villains), humor, intertwining plots writ from small and personal to huge and galaxy-encompassing, intrigue and war both old and new, mysterious ancient ruins and quirky intelligent spaceships. The developing intersection of a medieval world and a far-future one is wonderful to watch and covers well the secondary theme of “Who watches the Watchers?”

And then Banks does something that would be unforgivable in any other kind of story, and is nearly unforgivable here. His answer to the main theme, that which asks the point of the lives and fates of beings of mere matter, begins to rise, stalking towards Bethlehem.

So what does Banks do?

He takes everything he built and tears it all down.

This pissed me off, because, y’know, I made the mistake of getting attached to the plot threads, even though I knew ahead of time that, given the nihilistic theme that became more and more apparent, the collision of the two plots just could not end well. I don’t mind characters dying—gods know that a Martin lover needs to deal with frequent beloved/main characters’ nasty deaths—but Banks didn’t just destroy characters, but entire plots.

I should have known that Banks writes in service of the Idea first and foremost.

After Matter, I devoured more Culture novels in an attempt to divine some formula by which I might come to terms with Matter.

I learned that Banks isn’t known for endings that satisfy plot or character. After the Idea is explored, he’s lost almost all interest. His books are the epitome of the tight ending: no more and no less. Sometimes I think his editor has to club him into writing an epilogue.

His books are excellent, exquisite in their handling of story. He’s one of the best writers out there, in any genre or mainstream. But his books are, in sincerity, not for me.

A second admission: Banks made me despair of ever liking SF again. Any other book or story I attempted to read felt lifeless. I folded myself into the Dresden Files for two weeks after I discovered that I couldn’t even stomach epic low fantasy anymore.

Well played, Banks. Your story stayed with me.

I’ve written this review now, and it gives me a sense of closure I’m not ever getting from Banks.

Maybe the two SF anthologies I’m reading will unbreak me.

I’m a big Banks fan… but his late Culture novels seem to me too obviously nihilistic. I’m thinking of Inversions (never explicitly Culture, but told from the point of view of someone close to a Culture agent as far as I can tell) and Look To Windward. Banks is, I believe, an atheist, so his answer to the question of “what’s the point?” has usually been of the form “None, aside from what you make the point” which is, of course, the logical outcome of a materialist worldview. But it’s one thing to tell me a tale that uses that answer to inform the story and characters and another to bring the answer to the forefront.

I’ve not read Matter mostly because The Algebraist, though brilliantly written, similarly failed on its answer to the central mystery and I’m waiting for Matter to hit mass market paperback.

It’s odd… his early Culture novels gripped me… his later ones seem to tell me what Banks’ answer is, vs showing me and letting me draw my own conclusions. Use of Weapons, Consider Phlebas, Player of Games, Against a Dark Background… those are some of my favorite SF books, period. Excession was an amusing, fun book… but since then I get the feeling that he’s a little bored of the Culture. I think it might be time for it to transcend.

Yeah, I don’t know what it is about British SF writers these days, but why is the Idea (esp. the political one) so important to them, apparently to the exclusion of all else? I think Banks has some great ideas, but he too often makes the story serve them instead of the other way around which just often leads to bad, or unsatisfying, stories. Everyone has their own axe to grind, but I prefer it when the axe isn’t as obvious.

Also, I haven’t read all of his Culture stories, but when isn’t the hero someone with a “cool and sarcastic personality”?

I’m not agreeing with the opinions expressed so far, I’m afraid. I firmly believe that this is one of the best novels I’ve read in a long time. The two arms of the story are brilliantly crafted and, in my opinion, perfectly interwoven. I was intrigued from the start with how Iain Banks might bring both strands together and was not disappointed: it swept me along at a pace I enjoyed. I’ve read all of Mr Bank’s SF writings and not all are as “easy” as Matter. No criticism from me of this one, though.

Ah. Iain M. Banks…

It is true that Banks should be read only be trained professionals. But if you are ready for a Banks novel, what a ride!

Remember: a Banks novel will be set in a galaxy-spanning space-traveling future, inhabited by super-intelligent robots with jokey names, show bizarre technological and natural marvels of enormous scale, involve fearful fanatic antagonists who cannot be reasoned with, contain do-gooders who leave a cornucopiac utopia to try to help the less-fortunate using whatever means are necessary, and at the end those among the protagonists whom a malign fate has put at the end of the spear that might thwart the evil purposes of the antagonists will screw their courage to the sticking place, remember that the needs of the many outweigh the needs of the one, do what needs to be done, and die–or maybe not, if Banks is feeling *exceptionally* generous. There’s always hope–until the very last line…

@decco999 #3 –

Just a note: I loved the book, I thought it was an excellent book, I thought everything worked, I thought he pulled off every effect he intended, and the theme hung together very well. In short: brilliant.

But he’s still not for me, because my preference isn’t for the kind of stuff he does.

Banks pulled off one of the most glorious bastard-author gambits in this book, by putting the epilogue after the glossary. After the main body of the book ends — very abruptly — you turn the page to see a glossary, then promptly begin tearing your hair out, knowing you’ll never find out what happened. Only after you’ve come to terms with this ambiguity while paging through the glossary does he resolve your agony of unknowing. I love him for putting me through my paces like that, and I loved Matter overall, but I was quite ready to kick him in the kneecaps at the time.

@@@@@ jere7my #6 –

Yes, I thought that was a pretty dirty trick, and I actually loved him for it.

Banks is one of an elite group of mind-expanding writers [1]. You should’t read him if you’re not ready to face the hard stuff!

I actually think Banks is deceptively approachable; he can be read as a space opera even as he pulls attentive minds in unexpected directions.

Matter is not his most accessible work, but it’s one of his most penetrating books.

The rogue Culture Agent who seems two steps over the brink of madness is particularly interesting.

[1] The rest of ’em on this Amazon list:

http://www.amazon.com/gp/richpub/listmania/fullview/R31FWMEF05SUL8/ref=cm_lm_pthnk_view?ie=UTF8&lm_bb=

@John #8

I loved the rogue dude-who-is-a-spaceship guy.

I thought Matter was accessible enough, although Use of Weapons is probably a better starting point.

I love Banks’ sense of humor, by the way. As in, that he has one, and it’s sprinkled liberally throughout. In a way, the Culture is one wide-faring high-tech-strung-out hippie colony.

Inversions is pretty explicitly a Culture book. Well, maybe explicitly is the wrong word, but unambiguously. One of the two foreign characters is an SC agent, complete with a drone companion, and the other is ex-Culture. He even told the people of that world about the Culture (“Lavishia”), or at least as much as they would understand, and hints at why he left.

And then, of course, there’s the little flourish. On the first page, “A Note on the Text”, we are told that Vossil “was, without argument, from a different Culture”, and not quite on the last page, but close, the last thing anyone heard from Vossil was “a note declining the invitation, citing an indisposition due to special circumstances.”

I like the book a lot. It’s short and relatively simple, and it largely works by indirection.

I hated it – and am relieved that others can describe what really put me off.

In fact, I only got through about 200 pages and decided it was a snotty, arrogant and ideologically obsessed novel.

I found it hard to relate to the characters, hard to immerse myself in the landscapes. It was told so dispassionately, that, I didn’t care.

I was somewhat put off with Banks’s nuking one of his plot threads with its potential unrealized, but then, it’s hardly unexpected. In _Against a Dark Background_ he does the same thing. In _Consider Phlebas_ he does the same thing but puts it at the end of the book so you can call it a tragedy instead.

It’s still a damn good book. I felt _Look to Windward_ was somewhat sub-par: this is back up at the top again.

I too was quite disappointed with the ending of Matter; however, I can’t remember if I read the epilogue beyond the glossary! I think I did, but I’m going to find my copy tomorrow and check again…

Overall Matter wasn’t bad IMO but doesn’t reach the heady, incredibly dark, heights of Use of Weapons.

austern @10:

“a note declining the invitation, citing an indisposition due to special circumstances.”

That could have been taken as a double-bluff; that unknown to the part of the Culture (it’s not a monolithic entity) that forwarded the invitation, Vossil was already a member of the Culture’s Special Circumstances section. After all, not all of SC’s activities are common knowledge to the rest of the Culture, and the argument could be made that SC are “a different Culture” too.

Multi-layered wordplay going on I thought.

I’m just waiting for Ikea to start offering a Darckense chair…

Seriously, Banks is right at the top of the SF pile as far as I am concerned. He delivers epic scenery, action, and mind-contorting philosophical interrogations, all without giving the reader more than a moment to pause for breath.

I really liked Matter, though the sheer darkness of the ending meant I haven’t re-read it yet. This is a very rare occurrence with me – I usually devour books when I first acquire them, and then re-read at a more leisurely pace a few months later to get all the nuances I missed the first time around. If only I had the patience to wait for paperbacks of his stuff rather than pre-ordering the hardback the day it’s available! Then I could take the book on my ridiculously long plane odyssey next week…

It must also be said that the Culture cycle is also a very interesting way to develop philosophical and political reflections on the potential role of “intelligent” machines in an advanced society: http://yannickrumpala.wordpress.com/2010/01/14/anarchy_in_a_world_of_machines/