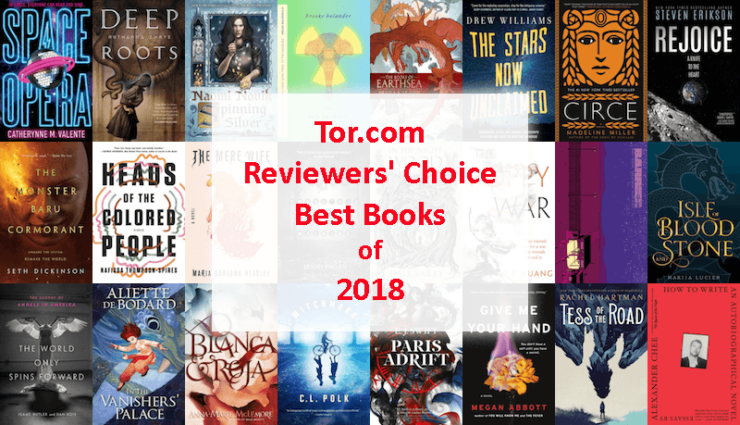

It’s been a year, hasn’t it? It started with losing Le Guin, and it’s hard to say it’s improved since then. But books? Those were good. We picked some favorites in the middle of the year, and now we’ve picked even more—some titles make a second appearance on this list, but as is usually the case, the second half of the year packed in a lot of winners. If your TBR stack isn’t already teetering, it will be after you read this list.

What did you love in this year’s reading?

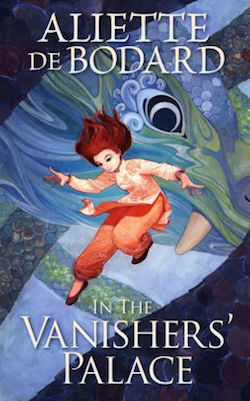

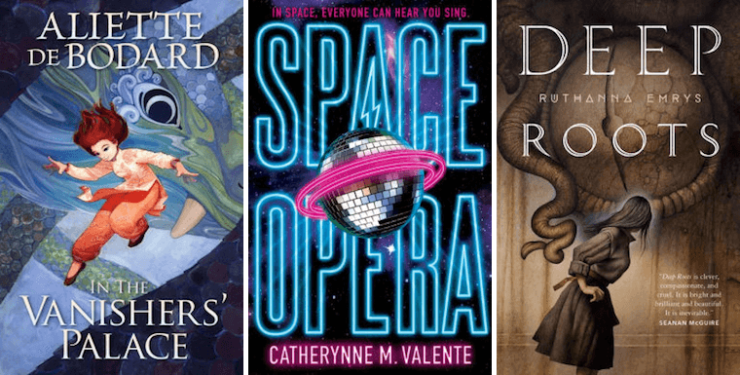

In the Vanishers’ Palace by Aliette de Bodard is a short novel. At around 50,000 words, it’s scarcely longer than a novella. And yet, of all the (many) books I’ve read in the last year, it’s the one that’s left the deepest impression: the one that cuts sharpest, and deepest, and most true. At the simplest level, it’s a variant on Beauty and the Beast, the complex—and complicated—interplay of necessity, agency, and affection between a scholar and a dragon. De Bodard’s prose is precise, elegantly beautiful, and her characters and worldbuilding are devastatingly brilliant. In the Vanishers’ Palace is a story about how the world is shit, but how it’s still possible to be kind. It’s a book I can’t help but love, and one that I expect I’ll return to many times in the years to come.

–Liz Bourke

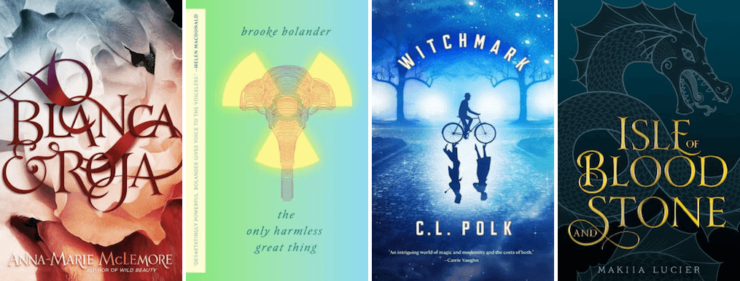

If you’ve never read anything by Anna-Marie McLemore, Blanca & Roja is a fantastic place to start. Inspired by “Snow White,” “Rose Red,” and “Swan Lake,” and lush with Latinx mythology subtext, this is a heart-wrenchingly beautiful young adult magical realism novel. In each generation of del Cisnes are born two sisters: one who will grow up into a woman and lead a normal life and another who will turned into a swan and stolen away by a local bevy. Everyone has assumes Roja will be taken by the swans, but Blanca will do anything to protect her sister. When two teenagers—nonbinary Page and reluctant prince Yearling—emerge from the woods, their liven entangle with the sisters. And since it’s written by McLemore, you know it’s poetic and powerful and devastating all at once.

Bo Bolander’s The Only Harmless Great Thing is one of those stories I can’t let go of. It haunts me all these months later. It’s my number one most recommended novellette. My own copy has been passed around since April. Bolander’s story, inspired by Topsy the elephant, radium girls, ray cats, and the atomic priesthood, is cutting and calculating, but not cold or cruel. It’s a tale of loss and love, of vitriol and spite, of need and want, of everything that is and should never be.

Although they are, content-wise, very different, Witchmark by C.L. Polk and Isle of Blood and Stone by Makiia Lucier have the same vibe. Witchmark tells the story of Miles, a doctor with secret magic powers, and Hunter, the otherworldly supernatural hunk of a man who he falls for as they uncover a murder and mass conspiracy. Isle of Blood and Stone is a young adult novel about three friends, King Ulises, Lady Mercedes, and mapmaker Elias, who set off on a quest to find man who is supposed to be dead. Lucier and Polk’s stories are light and airy and full of romance and adventure, but beneath their playful surfaces lie deeper truths about colonialism, abuses of power, and systemic oppression. There is far more to these two books than meets the eye.

–Alex Brown

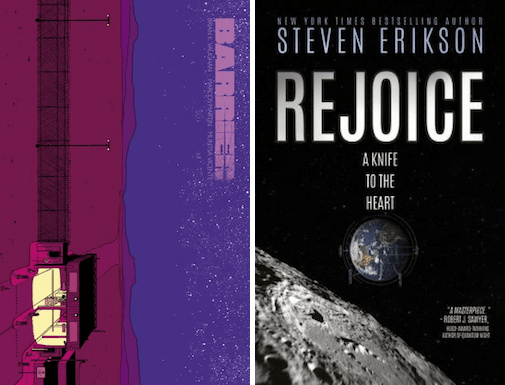

Admittedly, this one’s a bit of a cheat: Writer Brian K. Vaughan, artist Marcos Martin, and colorist Muntsa Vicente’s five-issue comic Barrier came out digitally back 2016 (and you can still pick it up that way, paying whatever you want via Panel Syndicate). But I’m sneaking it in because Image Comics physically published it in 2018—and over the past two years, the book has only grown more powerful and poignant. Written in both English and Spanish—with no translations for either—Barrier follows Liddy, a South Texas rancher, and Oscar, a refugee who’s endured a brutal journey from Honduras and now finds himself on Liddy’s land. That’s already a good setup to examine issues of illegal immigration… and the aliens haven’t even shown up yet. To say much more would be to give away Barrier’s potent surprises, but things get creepy, dark, and sharply insightful. Page after page, Liddy and Oscar’s journey is intense and inventive—and, in 2018, it’s also heartbreakingly relevant.

Thankfully, Rejoice, A Knife to the Heart, Steven Erikson’s novel about Earth’s first contact with extraterrestrials, isn’t nearly as stilted or self-serious as its goofy title. Erikson’s setup is simple: Aliens show up, promptly abduct science-fiction author Samantha August, and then start… well, fixing stuff. Endangered species find their habitats restored. Humans realize they can no longer physically harm each other. And a plan for an engine that runs on clean, inexhaustible energy shows up on hard drives across the world. Meanwhile, August hangs out in orbit, speaking with a clever alien A.I. about humanity’s catastrophic past and unknown future. Erikson’s impassioned novel doesn’t bother to conceal its examinations of contemporary issues—the book’s characters include barely disguised, and rarely complimentary, counterparts for the Koch brothers, Elon Musk, Rupert Murdoch, Donald Trump, and Vladimir Putin—and it’s all the better for it. As August decries and defends humanity, and as those on Earth grapple with unimaginable changes, Erikson mines The Day the Earth Stood Still and Star Trek to suggest that old-school sci-fi optimism could still serve as a counter to 2018’s horrific headlines. Well, that’s one reading, anyway. Another is that without help from super-advanced aliens, we’re all totally fucked.

–Erik Henriksen

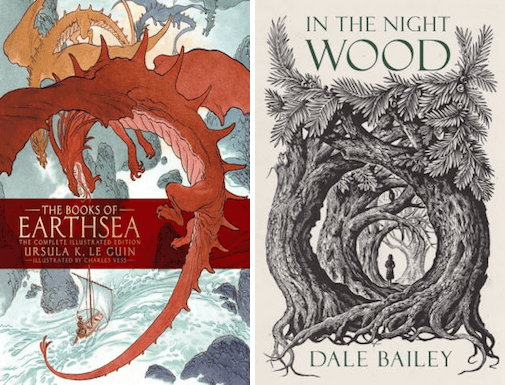

I first read Ursula Le Guin’s A Wizard of Earthsea as a high schooler in thrall to doorstop fantasy novels full of conventionally bloody heroism, and so the qualities that now most impress me—its spareness, its serenity—left me confused then. So I’m enjoying the opportunity to return to Earthsea (and to travel beyond the first book) with the recent release of The Books of Earthsea. Were the six books of Earthsea just printed together for the first time, Books would be a book of the year, but the Charles Vess illustrations, the uncollected stories, and the supplemental essays raise it above most anything else.

I tore through Dale Bailey’s In the Night Wood, a folk horror-fantasy hybrid full of green men and dark secrets that married an eventful plot with a study of grief in a very intense 200 pages. I’m currently reading Sarah Perry’s brilliant Melmoth, a literary Gothic fantasia perfect for the coming winter nights. Last but not least, I need to recommend Alan Garner’s beautiful memoir Where Shall We Run To?, which published in the UK this summer. Anyone who has been moved by Garner’s books, even readers put off by his uncompromising late style, should treasure this book. That it hasn’t been picked up for US publication is a scandal.

–Matthew Keeley

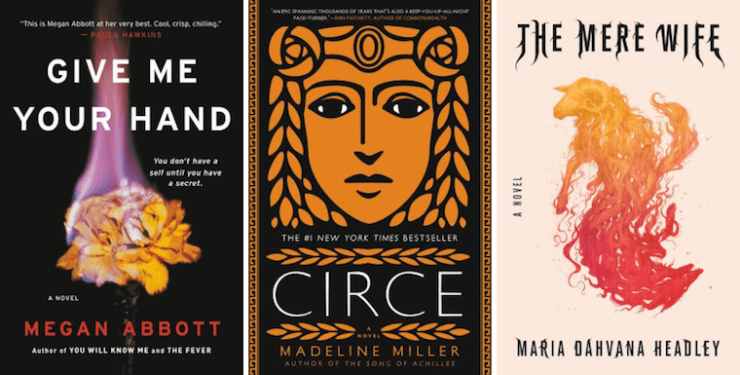

I’m a fangirl of Megan Abbott’s lean, mean writing, so of course I was going to enjoy her latest novel, Give Me Your Hand. I didn’t know just how much of an impact it would have though, because it did, with its taut, intense narrative about two young women scientists working on premenstrual dysphoric disorder research. Abbott is so deft at turning a thriller narrative inwards, forcing us to dip our fingers into the bloody souls of female friendships.

There have been a few revamps of ancient epics this year, and Madeline Miller’s Circe is one of the two I loved. It’s a gorgeous book ostensibly based on The Odyssey, but told from the perspective of the witch Circe, and is a glorious exploration of femininity and feminism, divinity and motherhood.

The second book based on an epic that will stay with me for a long while is Maria Dahvana Headley’s The Mere Wife, a sharp,visceral feminist take on Beowulf. Headley’s writing has rhythms I’ve always been fascinated by, and The Mere Wife is no exception to her unabashed no holds barred approach to any narrative. If Beowulf was a story about aggressive masculinity, The Mere Wife is one of femininity, where the female characters are more than just monster, hag, trophy—they are also in turn hero, saviour, leader.

–Mahvesh Murad

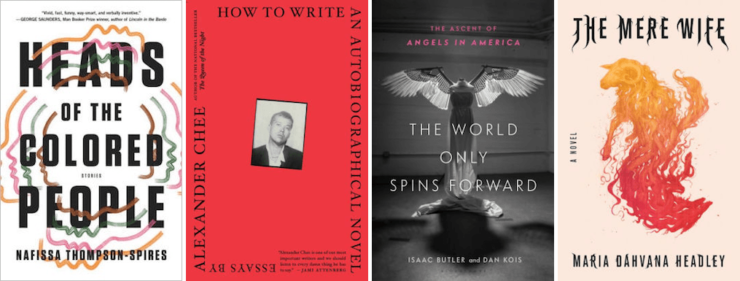

I already wrote about Heads of the Colored People’s title story in a TBR Stack post, but the whole collection is extraordinary, ranging from stories about a epistolary war between the mothers of the only two black girls in an elementary school class to intricate, layered explorations about how the white gaze infects a conversation between two very different black college students. Plus writing about it again gives me an excuse to link to Nafissa Thompson-Spires’ appearance on Late Night with Seth Meyers, in which she discusses television as an integral part of the writing process.

Alexander Chee’s How to Write an Autobiographical Novel is one of the best books of writing advice I’ve ever read, but so much more: Chee’s essays on craft and process will be useful to writers of any genre, and the essay “The Querent” asks real, tough questions about the ways some cultures can take deeply-held beliefs of another, and cast them as parlor tricks or speculative fiction. He also writes movingly of his lifelong activism and engagement with queer politics, and how that aspect of his life has shaped his sense of self. And as if all of that wasn’t enough his essay on creating a rose bower in the middle of Brooklyn will delight all the gardeners out there.

The World Only Spins Forward by Isaac Butler and Dan Kois is a fantastic oral history about one of my favorite plays. I have to say that as much as I loved all of the books I’ve recommended here, this one was the most sheer fun. I love oral histories as a format because, done well, they allow their editors to replicate the crosstalk of a good conversation, and TWOSF does not disappoint. Tony Kushner is garrulous and large-hearted as always, George C. Wolfe is incisive and seem to maybe have the best memory?), and each of the actors, directors, producers, teachers, angel designers—everybody gets to tell their part of the story and share this iconic history with the rest of us.

Maria Dahvana Headley’s The Mere Wife re-imagines the story of Beowulf, casting Grendel as an innocent boy named Gren, Dana Owens as his war veteran mother, and Willa Herot as the Queen Bee of Herot Hall, a fancy planned community built at the foot of the mountain. When Willa’s son forms an unlikely friendship with young Gren, it sets their mothers on a path that can only led to violent confrontation. And then Ben Woolf, former Marine, current cop, shows up, and things go from tense to explosive. Headley digs her claws into the meat of one of our oldest tales, and pulls out all the tendons that make it absolutely vital to our modern era.

–Leah Schnelbach

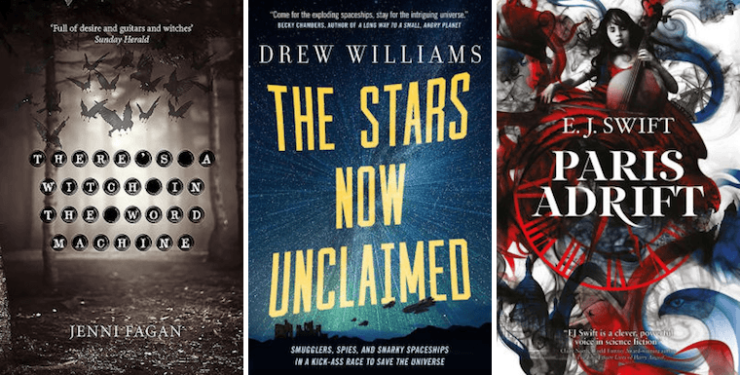

I swear by Jenni Fagan as one of the greatest living stylists of the written word. No new novel this year (so I’ve made time to reread The Sunlight Pilgrims). But… she published a slim new volume of poetry: There’s a Witch in the Word Machine. As the title indicates, these poems have a incantatory slant to them: part grimoire, part protest. As powerful and upsetting as they can be, there’s something addictive and hopeful about their faith in magic.

I mentioned Drew Williams’ The Stars Now Unclaimed at the midway point when (I cheated) it wasn’t even out yet. So it is only fair that I double-down. This space opera is bouncy and bounding in the best way: casually progressive and continuously entertaining. It is like revisiting the limitless joy of an old favourite, but upgraded with all the latest bells and whistles. Plus: zombie space raptors.

E.J. Swift’s Paris Adrift is beautiful, an ode to Paris (specifically) and romantic freedom (broadly). Cleverly composed, Paris Adrift begins with cataclysmic end of the world—and then steps sideways and backwards into the gloriously mundane. This is a book about love in a crisis; and learning to know yourself in an age of uncertainty. It is, if you’ll excuse the pun, timely. And, being a genuinely great book, will always be so.

–Jared Shurin

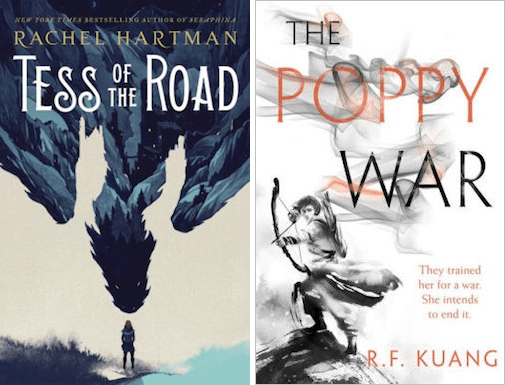

All year, I haven’t been able to put into words how much I love Rachel Hartman’s Tess of the Road. The third book set in the same world as Hartman’s Seraphina, Tess finds its title character (Seraphina’s half-sister) setting out on a stumbling road trip on which she finds a whole host of things we don’t always think of as heroic: truth, friendship, healing, honesty, and new ways of living in the world. But this is a heroic journey—one about healing from trauma, about retelling the story of yourself, and about coming to understand even the people you don’t really want to understand (including, sometimes, your own family). Stubborn, wounded Tess is a character I didn’t want to leave with the last page, and Hartman’s world grows bigger and bigger—and more inclusive—with every step of Tess’s journey. This is a book about compassion, about rape culture, about keeping moving when there’s little else you can do. It’s pointed and poignant, sharp and true, and the kind of book I know I’ll go back to again and again.

R.F. Kuang’s much-lauded debut, The Poppy War, eludes summation. There are layers upon layers to the story of the orphan Rin, who wins a place at the elite military school Sinegard and finds herself training in shamanism, in harnessing the power of a god in order to fight a powerful enemy. When war comes, it comes brutally, and nothing about it is easy—not dying, and not surviving, either. The setting is a secondary world, but Kuang’s story draws on Chinese history, including the Rape of Nanjing. “Almost every single reviewer has reeled from” specific chapters, Kuang writes in a post on her site about the necessity of brutality. I reeled, and I sat quietly, and I absorbed, and I understood the choices Rin makes after she sees what her enemy has done. I don’t just want to know what happens next; I need to know. But I’ve got months to wait: the sequel, The Dragon Republic, comes out in June.

–Molly Templeton

Aliette de Bodard’s fiction ranges from space opera to ruined Angel-ruled Paris, Aztec empire police procedurals and explorations of the interior lives of artificial intelligence. In the Vanishers’ Palace sits squarely in a post-apocalyptic science fantasy mode, something new and different, even if there are elements from her other work that meld together into a fusion that is more than the sum of its parts. From post-apocalyptic themes to dragons, to the legacy of colonial and cultural oppression, the insularity of village life, romance, family dynamics and much more, the author grounds the work in a tangled web of characters’ relationships. The trials, troubles, story drivers and worldbuilding all are wonderfully emergent from these character relationships. And this is all, at its base, the author’s take on a same sex version of the romance at the heart of Beauty and the Beast, between a human and a dragon. With all of these competing elements for the reader’s attention, it’s a balancing and juggling act that the author performs with confidence and success. In the Vanisher’s Palace showed me the consummate skill of the author’s ability.

Catherynne Valente’s Space Opera is a novel that is exuberantly fun, in a time and moment where such fun may seem frivolous and frothy and not serious. However, I hold the contrary view that such fun and frivolity is a tonic for people in these times. And it must be said, underneath of the chassis of this novel, which is the best combination of Eurovision and Hitchhikers Guide to the Galaxy that you could possibly ever imagine, there is a real beating heart of an ethos, an idea and a staked-out claim that science fiction can not only be fun and outwardly enthusiastically extroverted—but it can be well written and provide all the genre elements and invention at the same time. My knowledge of popular music, and Eurovision, is limited, and even with those limitations, I was carried along and through the themes and plot and characters of the novel by the sheer audacious flow of Valente’s writing. This is the novel I had the most fun reading all year.

Deep Roots, Ruthanna Emrys’ follow up to Winter Tide, deepens and enriches the Lovecraftian universe that Emrys brings to the page. With Aphra now having built a fragile but very real found family, her goal to find more of the blood of Innsmouth brings her to a place in its way as dangerous as any city beneath the ocean—New York City. While there, Aphra and her friends do find possible relatives, but also come into contact with more of the Lovecraftian universe, in the form of the Mi-Go, beings whose goals and directives toward humanity are not the same as Aphra, or even the Yith. Keeping her family together, forging relationships with her new relatives, and treating with the Mi-Go forces Aphra to become ever more a leader, whether she will, or not. It’s a lovely study and development of her character, and the relationships of those who connect around her. Emrys engages with Lovecraft’s body of work and makes it palatable and readable, and essential by having protagonists that, pointedly, Lovecraft would have never dreamed of writing from their point of view. It’s essential reading for those interested in Lovecraft’s legacy.

–Paul Weimer

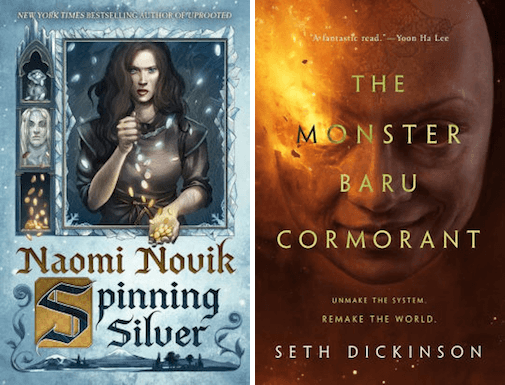

If I could have a new Naomi Novik standalone fantasy every three years, I would want for very little else. To call Spinning Silver simply a retelling of Rumpelstiltskin falls short of what it achieves, but it’s a good starting point: Novik begins with the familiar fairy tale conceit of a maiden trapped by her ability to conjure riches out of misery, then layers on commentaries into poverty, anti-Semitism, and money as the root of all evil, then lays down a glittering road of ice and crosses over it to a terrifying, cold kingdom. Basically, it’s Rumpelstiltskin meets The Merchant of Venice meets Robert Frost’s “Fire and Ice” poem, and it’s lovely.

Seth Dickinson’s The Monster Baru Cormorant had a lot to live up to after Traitor Baru; and while it didn’t shock and delight in the same ways, it triumphantly expanded the series’ universe while keeping Baru a compelling antihero. I had to read this book in fits and starts around other reading obligations, so that each time I returned to this dense tome was like reimmersing myself in deep water. Learning the new nations and players, revisiting the old ones, I felt like Baru herself, faced with the world map spread over the floor while playing the Great Game. To read this book is a challenge, but an intoxicating and satisfying one.

Every year I have to highlight the speculative short fiction that stuck with me longer than some books did. Whenever there’s a new Karen Russell story, I feel compelled to read it like a moth drawn to a flame, and “Orange World” captivates with its depiction of the desperate protectiveness of early motherhood. Judging by “The Pamphlet,” I’m likely to feel the same way about T Kira Madden’s fiction going forward: She weaves questions of racial identity and genetic inheritance into an unsettling ghost story that nonetheless made me tear up at its end.

I’m especially fond of those stories that futz with the medium and readers’ expectations of text. Like how Nino Cipri’s “Dead Air” unfolds through audio transcripts, establishing its own boundaries of white noise in brackets and then sneaking in otherworldly voices into that calming buzz. The fact that it stalwartly refuses to be a recording, to exist on the page instead of in your ears, actually heightens the creepiness factor. Then there’s Sarah Gailey’s “STET,” a brilliant, spiteful, poignant takedown of unfeeling near-future accident reports and overbearing editors, with the ingenious formatting (from the team at Fireside Fiction) to match.

–Natalie Zutter