October 7th marked the 161st anniversary of Edgar Allan Poe’s death, and as Halloween looms, it seems especially apt to focus on his foremost interpreter on the screen, producer-director Roger Corman. Between 1960 and 1964, Corman conflated a dozen of Poe’s poems and tales into eight films for American International Pictures (AIP), seven of them starring Vincent Price. Half of the cycle was written by Richard Matheson, whose friend Charles Beaumont worked on another three—Premature Burial (1962), The Haunted Palace (1963), and The Masque of the Red Death (1963); the last, The Tomb of Ligeia (1964), was written by future Oscar-winner Robert Towne.

Long associated with AIP, the legendary “King of the B’s” is now revered for the generation of filmmakers Corman nurtured on both sides of the camera. Matheson, meanwhile, had followed The Incredible Shrinking Man with a far less successful film, The Beat Generation (1959), and three diverse novels, all destined to reach the screen. Writer-director David Koepp filmed A Stir of Echoes (1958), minus its initial article, in 1999; Matheson adapted Ride the Nightmare (1959) as a 1962 episode of The Alfred Hitchcock Hour (remade in 1970 as Cold Sweat by James Bond mainstay Terence Young), and The Beardless Warriors (1960) as The Young Warriors (1968).

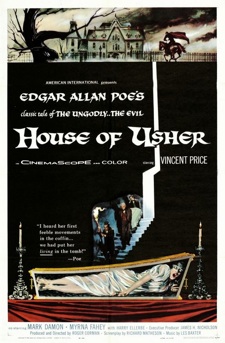

Beginning with House of Usher (1960), Matheson’s work for AIP dominated his screen career in the 1960s, and included some of his best-known films. Its title supposedly shortened from Poe’s “The Fall of the House of Usher” to fit on cinema marquees, the project was a bit of a gamble for AIP honchos James H. Nicholson and Samuel Z. Arkoff. Corman convinced them that instead of backing another pair of exploitative black-and-white programmers, they should devote a bigger budget and longer shooting schedule to a full-color adaptation of an established literary classic, one already familiar to AIP’s teenaged audiences and, not coincidentally, in the public domain.

A sizable chunk of Usher’s almost-$300,000 budget secured the services of its only star, Price, known for such genre films as House of Wax (1953) and William Castle’s House on Haunted Hill and The Tingler (both 1959). With snow-white hair and “a morbid acuteness of the senses,” Roderick Usher is played to perfection by Price as the fear of propagating his tainted line leads him to entomb his cataleptic sister, Madeline (Myrna Fahey), alive. Corman customarily hired seasoned pros like Price, who knew what they were doing, and left the younger actors—e.g., Mark Damon as Madeline’s suitor, Philip Winthrop—largely to their own devices as he concentrated on the camera.

A sizable chunk of Usher’s almost-$300,000 budget secured the services of its only star, Price, known for such genre films as House of Wax (1953) and William Castle’s House on Haunted Hill and The Tingler (both 1959). With snow-white hair and “a morbid acuteness of the senses,” Roderick Usher is played to perfection by Price as the fear of propagating his tainted line leads him to entomb his cataleptic sister, Madeline (Myrna Fahey), alive. Corman customarily hired seasoned pros like Price, who knew what they were doing, and left the younger actors—e.g., Mark Damon as Madeline’s suitor, Philip Winthrop—largely to their own devices as he concentrated on the camera.

Although introducing a romance with what had been Poe’s nameless narrator, and revving up his somber ending to a traditional Hollywood blaze (with footage of a burning barn that appeared in three more films in the cycle), Matheson’s script is generally true to its original author, who has perhaps never been better treated on the screen. The result was a critical and commercial success that ran all summer, sometimes on a double bill with Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho (1960). Neither AIP nor Corman had anticipated doing a Poe series, but circumstances dictated a follow-up, and after considering “The Masque of the Red Death,” they settled on “The Pit and the Pendulum.”

In between those efforts—published by Gauntlet as Visions of Death: Richard Matheson’s Edgar Allan Poe Scripts, Volume One—Matheson adapted AIP’s Master of the World (1961) from Jules Verne’s novel Robur, the Conqueror (aka The Clipper of the Clouds) and its eponymous sequel. In its more modest way, AIP clearly hoped to cash in on the success of Disney’s 20,000 Leagues Under The Sea (1954), and Robur (Price), who makes war on war with his futuristic Albatross, is obviously Verne’s airborne answer to his own Captain Nemo and Nautilus. But sadly, Western and serial vet William Witney’s uninspired direction and taciturn co-star Charles Bronson kept it from taking off.

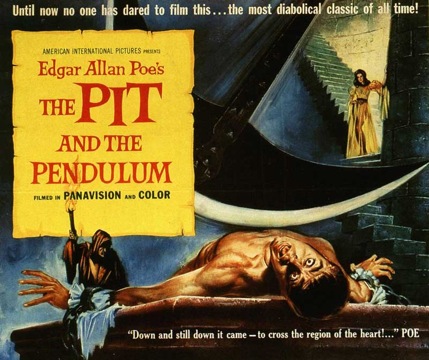

Its onscreen title also shy an initial article, Pit and the Pendulum (1961) bears more than a passing resemblance to Usher, perhaps because Poe’s tale lacks narrative thrust. Once again, the secretive Price presides over a forbidding structure to which the somewhat wooden young hero (Philip Kerr) comes, inquiring after a woman who is eventually revealed to have been entombed alive. In fact, Matheson merely imposed Poe’s set piece of a man tormented by the Inquisition as the final act of the screenplay, appending it to a plot he had largely derived from his outline for The House of the Dead, an uncompleted novel that was recently included in Matheson Uncollected: Volume Two.

Differentiating the two films is the fact that here, the object of the exercise, Elizabeth Medina (Barbara Steele), has faked her own death, colluding with family doctor Charles Leon (Antony Carbone) to drive her wealthy husband Nicholas (Price) mad. British-born Steele’s 1960s reign as Italy’s scream queen started with Mario Bava’s directorial debut, Black Sunday (1960), which AIP released in the U.S. with great success. The conspirators come to grief after succeeding too well, with Nicholas convinced he is his Inquisitor father; Charles and Elizabeth consigned to the pit and an iron maiden, respectively; and her brother Francis Barnard (Kerr) stuck under the pendulum.

Corman and his usual team pulled out all the stops for the climactic scenes in the torture room, later spoofed with Price in Norman Taurog’s AIP comedy Dr. Goldfoot and the Bikini Machine (1965). Production designer Daniel Haller removed the catwalks from the soundstage and built his sets all the way to the ceiling, while the illusion of the pit was convincingly created with a matte painting by that legendary master of the form, Albert Whitlock. Similarly, Price’s performance as Nicholas, at one point reeling off the many names for Hell, matched Floyd Crosby’s flamboyantly colorful photography, and was in marked contrast to the commendable restraint he had shown as Roderick.

Before continuing the Poe series, Matheson and his erstwhile television collaborator, Beaumont, adapted Fritz Leiber’s 1943 novel Conjure Wife into a speculative script (published exclusively in the Gauntlet edition of Christopher Conlon’s He Is Legend) and sold it to AIP. Because this story of a professor whose wife’s witchcraft furthers his career had previously been filmed as the Inner Sanctum mystery Weird Woman (1944), AIP had to acquire the rights from Universal, thus cutting into the screenwriters’ fee. Following controversial revisions by George Baxt, their only feature was filmed in England as Night of the Eagle (1962), released here as Burn, Witch, Burn.

Up next: Tales of Terror (1962) and The Raven (1963).

Matthew R. Bradley is the author of Richard Matheson on Screen, now on sale from McFarland, and the co-editor—with Stanley Wiater and Paul Stuve—of The Richard Matheson Companion (Gauntlet, 2008), revised and updated as The Twilight and Other Zones: The Dark Worlds of Richard Matheson (Citadel, 2009). Check out his blog, Bradley on Film.