In this bi-weekly series reviewing classic science fiction and fantasy books, Alan Brown looks at the front lines and frontiers of the field; books about soldiers and spacers, scientists and engineers, explorers and adventurers. Stories full of what Shakespeare used to refer to as “alarums and excursions”: battles, chases, clashes, and the stuff of excitement.

Author Roger Zelazny loved to use unlikely characters as protagonists. In Nine Princes in Amber, Corwin, a prince from a land of magic, talked and acted like someone out of a Dashiell Hammett detective novel. In Lord of Light, the powerful Enlightened One preferred to be called Sam. And in Damnation Alley, Zelazny set out to put the “anti” into “antihero” by picking Hell’s Angel and hardened criminal Hell Tanner for a heroic quest that takes him across the blasted landscape of a ruined United States. The result is a compelling look at what it means to be a hero, and stands as a perfect example of Zelazny’s trademark blend of poetic imagery and gritty action.

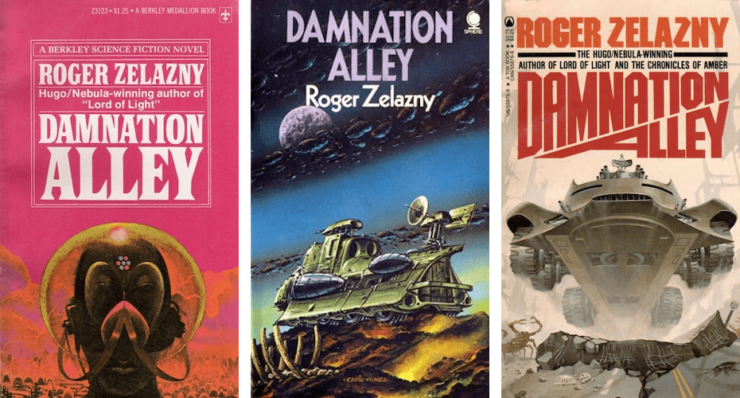

Damnation Alley first appeared in novella form in Galaxy magazine in 1967, and was then expanded to novel length in 1969 (although still a short novel by today’s standards). My copy of the book was printed in May of 1976, and I suspect I picked it up sometime in the following year. It had a sticker on one of the blank pages in the front announcing the movie version being released by 20th Century Fox. I suspect I bought it because of Zelazny’s name, and not because of the cover, which was one of those impressionistic paintings, so popular in that era, having little to do with the contents of the book (the artist is not credited, but I found it attributed to Paul Lehr on the internet). I also recollect buying it because I had heard about the movie, and wanted to read the book before seeing it…which turned out to be a huge mistake, because the movie wasn’t that good, and it was even worse when compared to the original source material (I’ll talk about the movie a bit later).

About the Author

Roger Zelazny (1937-1995) was one of the most popular American writers of fantasy and science fiction in the latter half of the twentieth century. I reviewed Zelazny’s work before when I looked at the first book of his famous Amber series, and that review contains a fairly extensive biography of the author.

Armageddon: Lots of Practice Writing About the End of the World

As a child of the 1950s, I grew up inundated with tales of the wars that would destroy civilization, and speculation on what kind of world might exist after that destruction. I’ve reviewed a few of them in this column over the years, and in my most recent review of a post-apocalyptic adventure, Hiero’s Journey by Sterling E. Lanier, I included a list of those previous reviews, and a discussion of the theme of post-apocalyptic worlds. Damnation Alley falls firmly into the most common post-apocalyptic setting portrayed in fiction during my youth, after a nuclear exchange leaves the United States in ruins.

Antiheroes

When I was young, the books I read were full of heroes. The protagonists were not just doers of great deeds, but their achievements were due to their positive qualities, such as ingenuity, courage and perseverance. There might be an occasional curmudgeonly engineer in Analog who did not suffer fools gladly, but in general those protagonists were as positive as they were plucky.

As I entered my teens, however, I began to encounter a different kind of protagonist. The New Wave was beginning to impact science fiction, and protagonists were often darker or flawed. And some of them, while they still achieved great deeds, did not do so because of any positive qualities at all. What I was encountering were tales where the protagonist was an antihero. There is a useful article in the online Encyclopedia of Science Fiction on the theme of antiheroes, which demonstrates that antiheroes had long been part of science fiction. One of the characters they cite is Jules Verne’s Captain Nemo, a figure who fascinated me when I saw the Disney version of 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea at a drive-in theater.

But the concept of the antihero can be slippery as well. A list of antiheroes on Wikipedia includes Donald Duck, a character who is a pain in the butt, but not especially anti- or heroic. It includes Errol Flynn’s Robin Hood, someone who I always considered purely heroic, a doer of great deeds, who did things that were illegal, but never immoral. And it includes Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid from the movie of the same name, who to me were just charming villains, and not heroic at all.

Hell Tanner, however, is a poster child for the modern antihero. He is a classical hero from the accomplishment standpoint, setting out to save a city full of people in a situation where no one else might succeeded. And other than his determination to do what he sets his mind on, he is a despicable person from the word go. If I met him in a gas station or convenience store, I would probably get back in the car, lock the doors, and go somewhere else to conduct my business. When I first read Damnation Alley, I hadn’t yet encountered a character quite like him, so the book hit me with the impact of a ton of bricks.

Damnation Alley

The book opens with Tanner on the run from the authorities in California. He is a swastika-wearing member of the Hell’s Angels motorcycle group (this was written back when gang members riding motorcycles were frequently portrayed as a menace, not like today when the average motorcycle rider appears to be a law-abiding citizen old enough to draw social security). Tanner has a long criminal record, but has gained notoriety as one of the only drivers who can successfully navigate the ruins that cover most of the country.

We find Tanner accepting a reward and a pardon, promising to drive across the country to Boston to deliver a vaccine that can cure a plague the Californians already faced. That cross-country trip will be through a stretch of land that is called Damnation Alley. Only one person has ever made the run, and that’s the man who brought news of the plague from Boston. But after agreeing to attempt the trip, Tanner tries to skip out on the job. We cut to Boston, where the city’s ruler is maddened by the constant tolling of bells that announce more deaths. And then Tanner is brought to a staging area where three armored vehicles have been prepared for the trip. He finds the authorities have convinced his brother to partner with him. He tells his brother where he can find some ill-gotten gains buried, and then breaks his ribs so he can’t make the trip. So, unlike the drivers of the other vehicles, Tanner will make the trip without a partner.

On the road, they face freakish weather where even rocks fall from the sky, as well as encountering giant Gila monsters and enormous bats. Zelazny explains that the weather prevents aircraft from flying, which deals with the old “why didn’t they just fly into Mordor?” issue, but doesn’t explain how giant bats are able to thrive. We get a description of the vehicles, eight-wheeled, windowless, armored, radiation shielded, with .50 caliber machine guns, grenade launchers, armor-piercing rockets, flamethrowers, and giant knife blades. If giant, tricked-out trucks are proof of manhood, Tanner is the manhood-iest guy on the road. One of the vehicles is destroyed, and Tanner takes its only surviving driver, Greg, as partner in his vehicle. They encounter multiple tornadoes and the second car disappears, never to be seen again. Tanner and Greg make it to Salt Lake City, where they can stop for repairs and resupply, but two out of three vehicles not surviving the ‘safest’ part of the run shows just how nasty the trip will be. At this point, having previously only showed us Tanner from outside his head, Zelazny brings us into the stream-of-consciousness flow of his thoughts that might be mistaken for one of those massive, run-on sentences from James Joyce’s Ulysses.

As Tanner and company make their way across the country, we get glimpses of the hopelessness in Boston, where people face almost certain death. The leader of Boston is despicable, but we also see heroic doctors, young lovers in despair, and we get a fuller sense of the importance of Tanner’s mission. On the road, Tanner faces radioactive ruins, more of those giant bats, and other threats. When Greg gets cold feet and wants to go back, Tanner beats him senseless and ties him up.

I’ll leave my recap there, as I don’t want to spoil the ending. Tanner is a fascinating character, although the deck is a bit stacked in his favor, as while we are told he has a reprehensible past, what we are shown is a tough but determined character whose entire focus is completing his mission. The ruined America, with its storms of gravel, giant mutant monsters, and radiation that stays in the vicinity of bombed cities (despite all those winds) is not scientifically accurate, but is a setting that feels plausible from a poetic or emotional standpoint. The book works very well as an adventure story, and also as a meditation on what heroism means. I particularly liked a scene where Zelazny shows a family of farmers saving Tanner from defeat, underscoring the fact that this horrible world still has some kindness and compassion left in it, and that cruel determination and individualism isn’t always enough to get the job done.

Damnation Alley (the Movie)

I’ve read that Zelazny expanded Damnation Alley to novel length at his agent’s recommendation in order to attract a movie deal. Zelazny reportedly was not happy with the novel version, and he might have saved everyone a lot of disappointment if he hadn’t written it, because the movie does not live up to the original tale in any way, shape, or form. While the first drafts of the movie script resembled the novel, the script as filmed was only loosely inspired by Zelazny’s work.

The movie is set after a nuclear war, and features horrible weather, fierce creatures, a ruined America and some cool armored vehicles—but other than that, it bears little resemblance to the book.

In the film, the plague in Boston does not exist, which immediately removes the heroic quest element that gave the book its power. And Tanner is an Air Force junior officer whose installation survives the war, which removes the “anti-” from the “hero.” Jan-Michael Vincent was a decent action star, but he was no Hell Tanner. The plot that replaced the original lacked its drive and intensity, the special effects were not compelling, and the movie concludes with an implausibly happy ending. The film went through all sorts of behind-the-scenes difficulties which drove up the cost, eventually underwent massive re-editing, and the special effects were problematic. The end result was a disappointing mishmash, the movie was panned by critics, and it went on to be a box-office bust.

Final Thoughts

For a young reader who had not encountered many true antiheroes before, Damnation Alley was an eye-opening experience. Hell Tanner was as repellent as he was compelling. The book had a raw energy, and at times, an almost poetical, allegorical feel. And almost 45 years later, I found it difficult to put down, and read it in large gulps over the course of only two evenings.

And now, I’m interested in your thoughts on either the book or the movie. Also, if anyone’s read both the original shorter version and the novel, I’d enjoy hearing your perspective on the differences between the two. And, as always, if there are other books you’d recommend with post-apocalyptic settings, we can chat about them as well.

Alan Brown has been a science fiction fan for over five decades, especially fiction that deals with science, military matters, exploration and adventure.