In this bi-weekly series reviewing classic science fiction and fantasy books, Alan Brown looks at the front lines and frontiers of the field; books about soldiers and spacers, scientists and engineers, explorers and adventurers. Stories full of what Shakespeare used to refer to as “alarums and excursions”: battles, chases, clashes, and the stuff of excitement.

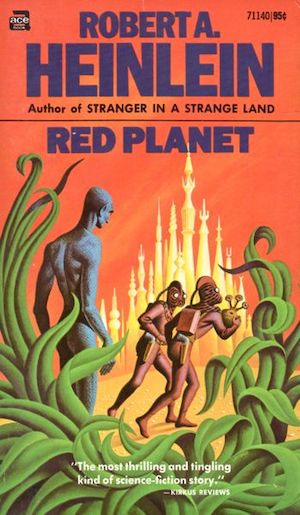

When I was young, Robert Heinlein’s juvenile novels were among my favorites. But I only got my hands on about half of them. Over the past few years, I have been working to find them all, and one of the most recent I was able to read was Red Planet. Imagine my surprise to find that the Martian race that I had first encountered in Stranger in a Strange Land had been created over a decade earlier for Red Planet…

In fact, while the novels are not otherwise connected, I have decided that Stranger in a Strange Land is actually a prequel to Red Planet.

This is the first time I have reviewed a book I’ve not technically read, having listened to it in a full-cast audio format. This format uses the text for the book, but in addition to the narrator, a cast of actors performs the dialogue. There are usually some minor alterations, as the narrator does not have to say, for example, “Tom said swiftly,” when we just heard the actor playing Tom read the line swiftly. It is not quite a radio play, complete with sound effects and music, but the format is an engaging way to experience a story. I did end up buying a copy of the book to refer to as I wrote this review, but still have not read the text in its entirety.

The version I listened to was put together by a company called Full Cast Audio, founded by author Bruce Coville. They had done a number of outstanding adaptations of the Heinlein juveniles, but when I met Coville at a convention a few years ago, he told me the licenses proved too expensive, and they were unable to continue the project. I have not found these adaptations available anywhere in electronic form (I suspect because of that rights issue), but if you poke around, you can find used copies of the CD versions, especially in library editions.

I will also note that Jo Walton previously written about this book for Tor.com, and her review can be found here. I avoided reading her review before doing mine, so you can see where our opinions converged and differed.

About the Author

Robert A. Heinlein (1907-1988) is one of America’s most widely known science fiction authors, often referred to as the Dean of Science Fiction. I have often reviewed his work in this column, including Starship Troopers, Have Spacesuit—Will Travel, The Moon is a Harsh Mistress, Citizen of the Galaxy, “Destination Moon” (contained in the collection Three Times Infinity), and The Pursuit of the Pankera/The Number of the Beast. Since I have a lot to cover in this column, rather than repeat biographical information here, I will point you back to those reviews (and note that a discussion of the juvenile series he wrote for Scribner’s is contained in the review of Have Spacesuit—Will Travel).

Heinlein’s Martians

I have long been a fan of Stranger in a Strange Land (written in 1961), and have read it a number of times. And while they never appear on stage during the book, I was always fascinated by the Martians who raise Valentine Michael Smith, teaching him to do things no other humans thought possible. He has psychic powers that include the ability to “disappear” people who threaten him, psychokinesis, and teleportation. He tells of how Mars is ruled by the Old Ones, Martians who have discorporated and no longer inhabit physical bodies. He puts a great deal of importance on sharing water, and makes a ceremony of it. He believes that all people and all things of creation are part of God. And he has the ability to “grok” (which is a word that means not just fully understanding and appreciating someone or something, but a whole lot more).

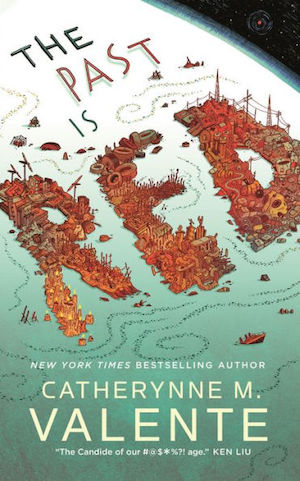

Buy the Book

The Past Is Red

Smith was born to members of the first Mars expedition, which ended in disaster, and was forgotten during the Third World War. When the second Mars expedition was sent out a couple of decades later, they were shocked to discover a survivor of the first expedition, young Mike Smith, who the Martians had raised, and then directed to return to his own world. Smith, with his potential legal ownership of Mars and his mysterious abilities, poses a threat to the powers that be, and ends up starting a new religion.

Red Planet (written in 1949) takes place perhaps decades later, when humans have begun to colonize Mars. The Martians who built the great canals and live in some of the now-deteriorating cities are seen as a dying race, and do not object when the humans begin to construct atmosphere plants that will transform Mars into a more Earth-like environment. Young Jim Marlowe, because of his kindness to a small Martian creature he calls Willis, befriends the Martians, whose form resembles a large, flexible tree. They often retreat from the world to contemplate, commune with their dead, share water with their friends, and they possess mysterious powers. There is no mention of grokking in Red Planet, and some of the other more religious aspects of Martian philosophy are absent, but nothing contradicts what we learn in Stranger in a Strange Land. And as the humans will discover, the Martians have not so much retreated from the physical world as transcended it, and are anything but a weak and dying race.

Other than Heinlein’s use of the same Martian race, along with a similarly oppressive world government for humanity, there is no clear link between the two books. But it is easy to imagine Mike Smith’s new religion, no matter how powerful its teachings, taking many years, if not decades, to be widely accepted by humanity. And to imagine as well that the human powers-that-be, even years later, might still be underestimating the abilities of the Martian race. So, until someone convinces me otherwise, I now categorize Stranger in a Strange Land as a prequel to Red Planet.

Red Planet

The book is the third juvenile that Heinlein wrote for Scribner’s. The first, Rocket Ship Galileo, was similar to a number of earlier juvenile science fiction novels, with a group of young boys helping an older scientist build a rocket ship (the Great Marvel Series of decades before [one of which I reviewed here] was among many that used this same theme). The second, Space Cadet, was a reimagining, in a science fiction setting, of Heinlein’s experiences at the Naval Academy and as a young naval officer. Red Planet represents a departure from these earlier tales, and in many ways, is a template for many Heinlein stories that will follow, both in juveniles, and books written for older audiences. The adventures of the protagonists are set against a background that in many ways resembles the American Revolution of the 18th century. And this book, like many of Heinlein’s other juveniles, displays a deep pessimism regarding mankind that is rather jarring for a book intended for children. Heinlein consistently portrays governments as inevitably deteriorating into tyranny, and human overpopulation leading inevitably to desperate expansion, war, and societal collapse. It is no wonder he sometimes clashed with his editors at Scribner’s.

Red Planet is set on a Mars that reflects a loose consensus among science fiction writers who used the planet in their stories during the early 20th century: a planet that is cooling and losing its atmosphere, and inhabited by a dying race that has built canals in an attempt to move water around the parched planet. The humans, without any resistance from the few remaining Martians, are building atmosphere plants to make the planet better able to accommodate colonists from an overcrowded Earth.

The book follows the adventures of Jim Marlowe and his buddy Frank Sutton as they leave home to attend boarding school in the human city of Lowell on the Martian equator. The boys are tough characters, used to wearing environmental suits and air masks, and packing sidearms to protect themselves from dangerous Martian predators. Jim brings with him a pet he rescued from some of those Martian predators—a “bouncer,” a spherical creature he has named Willis. Willis has a remarkable ability to reproduce and to remember everything it hears. Jim will be saying goodbye to his family, which includes his father, a leader in the colony; his mother; his pesky younger sister Phyllis; and his infant brother Oliver (this family introduces another frequent feature in Heinlein’s juveniles, a nuclear family conforming to rigid mid-20th century customs that may appear alien to modern readers). One of the people the boys will miss most when they go to boarding school is the old curmudgeonly Doctor MacRae (who readers will also recognize as a mouthpiece for many of Heinlein’s own opinions).

During a break in the journey of the canal boat that is transporting them, the boys explore a Martian city, encountering a Martian named Gekko and sharing water with him, although they do not yet realize the full import of that ceremony. Upon arrival at the boarding school, the boys find that the beloved headmaster of the school has been replaced by a prissy martinet named Mr. Howe. Howe is constantly implementing new and stricter rules, and one of them is to ban pets. When he finds Willis, he confiscates the creature and locks it in his office. He contacts the corrupt colonial administrator, Mr. Beecher, and the two cook up a plan to sell Willis to a zoo back on Earth.

The boys learn of this plan from Willis, whom they rescue from Howe’s office, thanks to its uncanny ability to reproduce sounds. And they also learn that Beecher has plans for the colony, which switches from the southern to northern hemisphere of the planet to avoid the harsh Martian winters. Beecher has plans to leave them where they are to allow more colonists to inhabit the northern hemisphere facility, not appreciating how difficult it will be for the colonists to survive a Martian winter.

With winter around the corner, the boys decide they must escape the school and travel home to give this news to their parents. The canals are beginning to freeze, and they resort to ice skating to make the long trek without being captured by the authorities. This arduous journey is one of the most interesting parts of the books, and is evocatively described by Heinlein (although my having grown up on a northern lake, spending many hours of my youth ice skating, might have something to do with why this section spoke to me so vividly).

The boys and Willis have another encounter with the Martians, who they learn are far stranger, and far more powerful, than anyone had previously imagined. When they arrive at home, the colonists—under the cautious leadership of Jim’s father, and at the urging of the rabble-rousing MacRae—decide to take matters into their own hands, and start the seasonal migration up the canal to the north hemisphere facility. But Beecher and his minions have other ideas, and soon the struggle over the fate of the colony turns into an open revolt, and Jim and Frank are on the front lines of a shooting war. The struggle brings the mysterious Martians out of their self-imposed isolation, with unpredictable consequences.

Heinlein does a good job portraying how a conflict can snowball into a revolution. Some of the characters (especially the background characters) are a bit one-dimensional, and the villains are predictable cads from central casting, but the story feels real and engaging. Jim comes across like an authentic adolescent, stubbornly sure of himself despite constant reminders he doesn’t know everything. And the Martians are delightfully alien, their behavior consistent and believable, but nothing like humans. Compared to the two juvenile books that preceded it, this one feels much more richly imagined, and much more distinctively a work of Heinlein.

Final Thoughts

I wish I had read Red Planet sooner, although I am very glad I finally encountered it. It immediately became one of my favorites among the Heinlein juveniles. The Martian race that the author created for this book went on to play a large role in his subsequent books, most vividly in the more widely known (and more adult-oriented) Stranger in a Strange Land, as discussed. The book introduces many of the overarching themes of freedom, exploration, and self-reliance that form the core of Heinlein’s later work. If you haven’t read it, I highly recommend it.

And now I turn the floor over to you: If you’ve read Red Planet, its prequel Stranger in a Strange Land, or just want to comment on Heinlein’s work in general, I’d love to hear your thoughts.

Alan Brown has been a science fiction fan for over five decades, especially fiction that deals with science, military matters, exploration and adventure.