Welcome back to the Lovecraft reread, in which two modern Mythos writers get girl cooties all over old Howard’s sandbox, from those who inspired him to those who were inspired in turn.

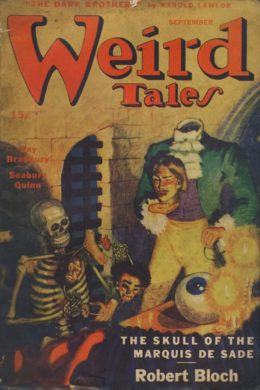

This week, we’re reading Ray Bradbury’s “Skeleton,” first published in the September 1945 issue of Weird Tales. Spoilers ahead.

“His heart cringed from the fanning motion of ribs like pale spiders crouched and fiddling with their prey.”

Summary

Mr. Harris’s bones ache. His doctor snorts that he’s “been curried with the finest-tooth combs and bacteria-brushes known to science” and there’s nothing wrong with him except hypochondria. Blind fool, Harris sulks. He finds a bone specialist in the phone directory: M. Munigant. This fellow, redolent of iodine, proves a good listener; when Harris has run through his symptoms, Munigant speaks in a strange whistling accent:

Ah, the bones. Men ignore them until there’s an imbalance, an “unsympathetic coordination between soul, flesh and skeleton.” It’s a complicated psychological problem. He shows Harris X-rays, “faint nebulae of flesh in which hung ghosts of cranium, spinal-cord, pelvis,” and Harris shudders.

If Mr. Harris would like his bones treated, he must be in the proper mood, must need help. Harris lies open-mouthed on a table, Munigant bending over him. Something touches Harris’s tongue. His jaws crack, forced outward, and his mouth involuntarily snaps shut, nearly on Munigant’s nose! Too soon, Munigant concludes. He gives Harris a sketch of the human skeleton. He must become “tremblingly” aware of himself, for skeletons are “strange, unwieldy things.”

Back home, Harris studies both the sketch and himself. With mixed curiosity and anxiety, he fingers his limbs, probes skull and torso with the painstaking zeal of an archaeologist. His wife Clarisse, utterly at home in her lithe body, tells him it’s normal for some ribs to “dangle in midair” as Harris puts it—they’re called “floating ribs.” Fingernails are not escaping bone, just hardened epidermis. Won’t he stop brooding?

How can he stop, now he realizes he has a skeleton inside him, one of those “foul, dry, brittle, gouge-eyed, skull-faced, shake-fingered, rattling things that lie “on the desert all long and scattered like dice!” Yet all three must be right, doctor and Munigant and Clarisse. Harris’s problem’s in his head, not in his bones. He can fight it out with himself. He really should set up the ceramics business he’s been dreaming of, travel to Phoenix to get the loan.

Trouble is, the conflict between Harris’s interior and exterior grows. He begins to perceive his outside person as lopsided of nose, protuberant of eye, whereas the skeleton’s “economical of line and contour… beautiful cool clean calciumed.” Whenever Harris thinks he’s the one who commands the skeleton, the skeleton punishes him by squeezing brain, lungs, heart until he must acknowledge the real master.

Clarisse tries to convince him there’s no division between his exterior and his skeleton—they’re “one nation, indivisible.” Harris wants to buy that. His skeleton doesn’t—when he tries to consult Munigant again, he flees the office with terrible pains. Retreating to a bar, he wonders if Munigant’s responsible—after all, it was Munigant who fixed Harris’s attention on his skeleton. Maybe he has some nefarious purpose, but what? Silly to suspect him.

At the bar Harris spots an enormously fat man who’s obviously put his skeleton in its place. He works up courage to ask the man his secret and gets a semi-jovial, semi-serious reply: he’s worked on his bulk from boyhood, layer by layer, treating his innards like “thoroughbreds,” his stomach a purring Persian cat, his intestines an anaconda in the “sleekest, coiled, fine and ruddy health.” Also essential? Harris must surround himself with all the “vile, terrible people [he] can possibly meet,” and soon he’ll build himself a “buffer epidermal state, a cellular wall.”

Harris must think Phoenix is full of vile people, because this encounter inspires him to take the trip. He’ll get his business loan, but not before a harrowing accident in the Mojave Desert. Driving through a lonely stretch, the inner (skeletal) Harris jerks the wheel and plunges the car offroad. Harris lies unconscious for hours, then wakes to wander dazed. The sun seems to cut him—to the bone. So that’s Skeleton’s game, to parch him to death and let the vultures clean away the cooked flesh, so Skeleton can lie grinning, free.

Too bad for Skeleton a policeman rescues Harris.

Home again, loan secured and Clarisse jubilant, Harris masks his desperation. Who can help? He stares at the phone. When Clarisse leaves for a meeting, he calls Munigant.

As soon as he sets the phone down, pain explodes through his body. An hour later, when the doorbell rings, he’s collapsed, panting, tears streaming. Munigant enters. Ah, Mr. Harris looks terrible. He’s now psychologically prepared for aid, yes? Harris nods, sobs out his Phoenix story. Is Munigant shrinking? Is his tongue really round, tube-like, hollow? Or is Harris delirious?

Munigant approaches. Harris must open his mouth, wide. Wider. Yes, the flesh cooperates now, though the skeleton revolts. His whistling voice gets tiny, shrill. Now. Relax, Mr. Harris. NOW!

Harris feels his jaw wrenched in all directions, tongue depressed, throat clogged. The carapaces of his skull are riven, his ribs are bundled like sticks! Pain! Fallen to the floor, he feels his limbs cast loose. Through streaming eyes he sees—no Munigant. Then he hears it, “down in the subterranean fissures of his body, the minute, unbelievable noises; little smackings and twistings and little dry chippings and grindings and nuzzling sounds—like a tiny hungry mouse down in the red-blood dimness, gnawing ever so earnestly and expertly….”

Turning the corner for home, Clarisse almost runs into a little man crunching on a long white confection, darting his odd tongue inside to suck out filling. She hurries to her door, walks to the living room and stares at the floor, trying to understand. Then she screams.

Outside the little man pierces his white stick, crafting a flute on which to accompany Clarisse’s “singing.”

As a girl she often stepped on jellyfish on the beach. It’s not so bad to find an intact jellyfish in one’s living room. One can step back.

But when the jellyfish calls you by name….

What’s Cyclopean: Rich language makes the familiarity of the body strange: “faint nebulae of flesh,” “grottoes and caverns of bone,” “indolently rustling pendulums” of bone.

The Degenerate Dutch: In places where a lesser writer might show Harris’s fear of his own body through judgment of others, Bradbury has Harris appreciating the way others’ bodies differ from his own. Women can be calm about having skeletons because theirs are better padded in the breasts and thighs (even if their teeth do show). A fat man in a bar is drunkly cynical about his own weight, but Harris yearns for such an overmatched skeleton.

Mythos Making: Munigent, with his hollow, whistling tongue, makes for a subtle monster, but deserves a place alongside the most squamous and rugose Lovecraftian creations.

Libronomicon: No books, but X-rays are compared to monsters painted by Dali and Fuseli.

Madness Takes Its Toll: PTSD and supernaturally-inflamed dysphoria make for a terrible combination.

Buy the Book

Deep Roots

Ruthanna’s Commentary

It’s stories like this that make me wish all authors’ writing habits were as well-documented as Lovecraft’s. “Skeleton” appeared in Weird Tales in the September 1945 issue. That would be one month after the end of World War II, unless the issue was on newsstands a little early, as issues normally are. Pulp response times were pretty quick, so it’s just vaguely possible that Bradbury sat down on August 6th, banged out a story about people convinced to feed their skeletons to monsters, and had it out to the public in time for Japan’s final surrender. I can think of far less sensible reactions, honestly.

Or on a more relaxed timeline, the German surrender in May could have inspired him to think “people hating their skeletons, that’s what I want to write about.” Which seems like more of a stretch, but then my fictional reflexes are a lot different from Ray Bradbury’s.

Either way, “The war was just over” seems like the heart of the story, the bones beneath all Harris’s fears and neuroses. Bradbury needn’t draw the connecting ligaments. There are any number of possibilities, but here’s a likely one: a young man recently mustered out of the army, trying to get by in the less regimented world of post-war work, his PTSD coming out as barely-more-socially-acceptable hypochondria, his doctor as uninterested as most were in the reality of his aftershocks.

Bradbury himself wasn’t permitted to join up due to poor eyesight, and spent the war years building his writing career. You could probably build a pretty good taxonomy of classic SF authors by their reactions to the wars of the 21st century—gung-ho, confidently patriotic, cynical, virulently pacifist—and when and whether they served in the military. “Skeleton” reminds me a bit of “Dagon”—both by authors never given the opportunity to fight, but well-aware that it broke people.

Harris’s wife Clarisse makes a counterpoint to his brokenness. I like her, and I have a hunch about her: what kind of woman cheerfully spouts anatomy lessons and knows how to talk someone down from a panicked rant without freaking out herself? I’m guessing that she served too, probably as a nurse treating men just off the front lines. I love her even more than I love the guy in the bar who announces that his intestines are the rarest purebred anacondas. She knows what she’s doing, possibly the only person in the story who does—aside from M. Munigant.

I don’t know what’s creepier about Munigant—his diet, or his hunting methods. No, I do know. There are plenty of osteophages in the world, but most of them get their calcium from dead things—either going in after meat-loving scavengers have picked them dry, or at the very worst having them for dessert after appreciating the rest of the carcass. Nature, weird in tooth and claw, sure, that’s fine. Munigant’s methods are unique. Just convince your prey to see their own skeleton as an enemy! It shouldn’t be hard—after all, if you think about it, it’s pretty strange to have this thing inside you, where you can never see it. Hard bones, better suited to hanging pendulous from castle ramparts or scattered picturesquely in desert dioramas.

Maybe you’d better not think about it too hard.

My reaction to this type of discomfort with physicality tends toward adamant refusal. It reminds me too much of the priest in Geraldine Brooks’s Year of Wonders who resists feminine temptation by thinking about how gross potential partners’ insides are. I’m more of a mind with Spike, reassuring Drusilla that he loves her “eyeballs to entrails, my dear.” But that kind of comfort with one’s own body is hard to come by. A predator who depends on people shuddering about their own insides… is going to feed well, and often.

Buy the Book

Fathomless

Anne’s Commentary

They arrived about the same time as the Lovecraft paperbacks I bought based solely on the gruesome yet strangely gorgeous demi-heads on the covers: two used paperbacks someone passed down to me, I can’t even remember who now. It might have been one of the nuns at St. Mary’s elementary school, who was cleaning out the book closet and who, coming across these two lightly tattered treasures, knew exactly which fifth-grader would appreciate them most. That’s right, yours truly, already infamous for drawing the Starship Enterprise and Dr. McCoy on her notebooks. (We were not supposed to draw on our notebooks. Although if it was Jesus or the Virgin Mary, you might get away with it. Starfleet officers did not cut it.)

One of the used paperbacks was The Martian Chronicles. The other was The October Country. I read them both that summer after fifth grade, lying on the old couch on the back porch and sweating. Sometimes it was because it was 90º out and King, our neighbors’ massive white German Shepherd, was lying on my legs. More often it was because I was under the spell of a grandmaster storyteller and experiencing, I now think, not just the considerable pleasure of the fiction itself but also some of the exhilaration, the joy, the author had in writing it. Long after that summer, I would read this in Bradbury’s Zen in the Art of Writing about another October Country companion of today’s “Skeleton”:

The day came in 1942 when I wrote “The Lake.” Ten years of doing everything wrong suddenly became the right idea, the right scene, the right characters, the right day, the right creative time… At the end of an hour the story was finished, the hair on the back of my neck was standing up, and I was in tears. I knew I had written the first really good story of my life.

And hey! When I read “The Lake,” my neck hairs were up, and I was in tears! Ditto for “Skeleton,” except I wasn’t in tears. I was more in luxuriously shuddersome gross-out.

If any writer deserves the honorary Anglo-Saxon (and Rohirrim!) name of Gieddwyn (Wordjoy), it would be Ray Bradbury. Give him the least spark of inspiration as he’s strolling along, and bang! The dam’s blown to the moon, the flood’s released, and Ray’s on a wild kayak ride on the crest of it! Once he realizes, for Harris, that the skull is a curved carapace holding the brain like an electric jelly, you think he’s going to stop there? Some might say he should. It’s a fine metaphor. It’s plenty. No. Not for Ray. Not for the Ray-attuned reader. We are ready to go on the headlong plunge into skulls like cracked shells with two holes shot through by a double-barreled shotgun, by God! Skull like grottoes and caverns, with revetments and placements for flesh, for smelling, seeing, hearing, thinking! A skull that encompasses the brain, allowing it exit through brittle windows. A skull in CONTROL, hell yeah. You believe it now, don’t you? You feel the panic.

Speaking of panic, I was about to write that Lovecraft feels more persnickety with words than Bradbury. But in moments of intense character emotion, terror or awe or his signature combination of the two, Howard can verbally inundate the page right up there with Ray, though with quite a different log-jam of vocabulary.

And, already running out of room before I can speculate on whether Harris has the worst case of quack-aggravated body dysmorphic disorder ever. And just what the hell kind of monster is M. Munigant? An osteophage? Are there others in world mythology? What about the “Skeleton” episode of Ray Bradbury Theater in which Eugene Levy gets to play his born-to role as ultimate hypochondriac?

And “The Jar,” which follows “Skeleton” in my October Country, and isn’t it all how we NEED the terror and awe? Grows the list!

Next week, for real HPL completists, “Sweet Ermengarde.”

Ruthanna Emrys is the author of the Innsmouth Legacy series, including Winter Tide and Deep Roots. Her neo-Lovecraftian stories “The Litany of Earth” and “Those Who Watch” are available on Tor.com, along with the distinctly non-Lovecraftian “Seven Commentaries on an Imperfect Land” and “The Deepest Rift.” Ruthanna can frequently be found online on Twitter and Dreamwidth, and offline in a mysterious manor house with her large, chaotic household—mostly mammalian—outside Washington DC.

Anne M. Pillsworth’s short story “The Madonna of the Abattoir” appears on Tor.com. Her young adult Mythos novel, Summoned, is available from Tor Teen along with sequel Fathomless. She lives in Edgewood, a Victorian trolley car suburb of Providence, Rhode Island, uncomfortably near Joseph Curwen’s underground laboratory.